Fructose malabsorption

| Fructose malabsorption | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fructose | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E74.3 |

| ICD-9-CM | 271 |

| OMIM | 138230 |

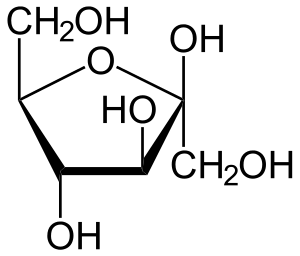

Fructose malabsorption, formerly named "dietary fructose intolerance" (DFI), is a digestive disorder[1] in which absorption of fructose is impaired by deficient fructose carriers in the small intestine's enterocytes. This results in an increased concentration of fructose in the entire intestine.

Occurrence in patients identified to be suffering symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome is not higher than occurrence in the normal population. However, due to the similarity in symptoms, patients with fructose malabsorption often fit the profile of those with irritable bowel syndrome.[2] In some cases, fructose malabsorption may be caused by several diseases which cause an intestinal damage, such as celiac disease.[3]

Fructose malabsorption is not to be confused with hereditary fructose intolerance, a potentially fatal condition in which the liver enzymes that break up fructose are deficient.

Symptoms

Fructose malabsorption may cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence or diarrhea.[4][5]

Pathophysiology

Fructose is absorbed in the small intestine without help of digestive enzymes. Even in healthy persons, however, only about 25–50 g of fructose per sitting can be properly absorbed. People with fructose malabsorption absorb less than 25 g per sitting.[6] Simultaneous ingestion of fructose and sorbitol seems to increase malabsorption of fructose.[3] Fructose that has not been adequately absorbed is fermented by intestinal bacteria producing hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane and short-chain fatty acids.[4][7] This abnormal increase in hydrogen may be detectable with the hydrogen breath test.[3]

The physiological consequences of fructose malabsorption include increased osmotic load, rapid bacterial fermentation, altered gastrointestinal motility, the formation of mucosal biofilm and altered profile of bacteria. These effects are additive with other short-chain poorly absorbed carbohydrates such as sorbitol. The clinical significance of these events depends upon the response of the bowel to such changes. Some effects of fructose malabsorption are decreased tryptophan,[8] folic acid[9] and zinc in the blood.[9]

Restricting dietary intake of free fructose and/or fructans may provide symptom relief in a high proportion of patients with functional gut disorders.[10]

Diagnosis

The diagnostic test, when used, is similar to that used to diagnose lactose intolerance. It is called a hydrogen breath test and is the method currently used for a clinical diagnosis. Nevertheless, some authors argue that this test is not an appropriate diagnostic tool because of a negative result does not exclude a positive response to fructose restriction.[3]

Treatment

There is no known cure, but an appropriate diet and the enzyme xylose isomerase can help.[3] The ingestion of glucose simultaneously with fructose improves fructose absorption and may prevent the development of symptoms. For example, people may tolerate fruits such as grapefruits or bananas, which contain similar amounts of fructose and glucose, but apples are not tolerated because they contain high levels of fructose and lower levels of glucose.[4]

Xylose isomerase

Xylose isomerase acts to convert fructose sugars into glucose. Dietary supplements of xylose isomerase may ameliorate the symptoms of fructose malabsorption.[3]

Diet

Foods that should be avoided by people with fructose malabsorption include:

- Foods and beverages containing greater than 0.5 g fructose in excess of glucose per 100 g and greater than 0.2 g of fructans per serving should be avoided. Foods with >3 g of fructose per serving are termed a 'high fructose load' and possibly present a risk of inducing symptoms. However, the concept of a 'high fructose load' has not been evaluated in terms of its importance in the success of the diet.[11]

- Foods with high fructose-to-glucose ratio. Glucose enhances absorption of fructose, so fructose from foods with fructose-to-glucose ratio <1, like white potatoes, are readily absorbed, whereas foods with fructose-to-glucose ratio >1, like apples and pears, are often problematic regardless of the total amount of fructose in the food.[12]

- Foods rich in fructans and other fermentable oligo-, di- and mono-saccharides and polyols (FODMAPs), including artichokes, asparagus, leeks, onions, and wheat-containing products, including breads, cakes, biscuits, breakfast cereals, pies, pastas, pizzas, and wheat noodles.

- Foods containing sorbitol, present in some diet drinks and foods, and occurring naturally in some stone fruits, or xylitol, present in some berries, and other polyols (sugar alcohols), such as erythritol, mannitol, and other ingredients that end with -tol, commonly added as artificial sweeteners in commercial foods.

- Foods containing High fructose corn syrup.

Foods with a high glucose content ingested with foods containing excess fructose may help sufferers absorb the excess fructose.[13]

The role that fructans play in fructose malabsorption is still under investigation. However, it is recommended that fructan intake for fructose malabsorbers should be kept to less than 0.5 grams/serving,[14] and supplements with inulin and fructooligosaccharide (FOS), both fructans, should be avoided.[14]

Foods with high fructose content

According to the USDA database,[15] foods with more fructose than glucose include:

| Food | Fructose (grams / 100 grams) | Glucose (grams / 100 grams) |

|---|---|---|

| Sucrose (for reference) |

50 | 50 |

| Apples | 5.9 | 2.4 |

| Pears | 6.2 | 2.8 |

| Fruit juice e.g. Apples, Pears |

5–7 | 2–3 |

| Watermelon | 3.4 | 1.6 |

| Raisins | 29.8 | 27.8 |

| Honey | 40.9 | 35.7 |

| High fructose corn syrup |

42–55 | 45–58 |

| Mango | 4.68 | 2.01 |

| Agave nectar | 55.6 | 12.43 |

The USDA food database reveals that many common fruits contain nearly equal amounts of the fructose and glucose, and they do not present problems for those individuals with fructose malabsorption.[16] Some fruits with a greater ratio of fructose than glucose are apples, pears and watermelon, which contain more than twice as much fructose as glucose. Fructose levels in grapes varies depending on ripeness and variety, where unripe grapes contain more glucose.

Dietary guidelines for the management of fructose malabsorption

Researchers at Monash University in Australia developed dietary guidelines[14] for managing fructose malabsorption, particularly for individuals with IBS.

Unfavorable foods (i.e. more fructose than glucose)

- Fruit – apple, pear, guava, honeydew melon, nashi pear, pawpaw, papaya, quince, star fruit, watermelon;

- Dried fruit – apple, currant, date, fig, pear, raisin, sultana;

- Fortified wines

- Foods containing added sugars, such as agave nectar, some corn syrups, and fruit juice concentrates.

Favorable foods (i.e. fructose equal to or less than glucose)

The following list of favorable foods was cited in the paper: "Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome Guidelines for effective dietary management".[14] The fructose and glucose contents of foods listed on the Australian food standards[17] would appear to indicate that most of the listed foods have higher fructose levels.

- Stone fruit: apricot, nectarine, peach, plum (caution — these fruits contain sorbitol);

- Berry fruit, blackberry, boysenberry, cranberry, raspberry, strawberry, loganberry;

- Citrus fruit: kumquat, grapefruit, lemon, lime, mandarin, orange, tangelo;

- Other fruits: ripe banana, jackfruit, passion fruit, pineapple, rhubarb, tamarillo.

Food-labeling

Producers of processed food in most or all countries, including the USA, are not currently required by law to mark foods containing "fructose in excess of glucose." This can cause some surprises and pitfalls for fructose malabsorbers.

Foods (such as bread) marked "gluten-free" are usually suitable for fructose malabsorbers, though sufferers need to be careful of gluten-free foods that contain dried fruit or high fructose corn syrup or fructose itself in sugar form. However, fructose malabsorbers do not need to avoid gluten, as those with celiac disease must.

Many fructose malabsorbers can eat breads made from rye and corn flour. However, these may contain wheat unless marked "wheat-free" (or "gluten-free") (Note: Rye bread is not gluten-free.) Although often assumed to be an acceptable alternative to wheat, spelt flour is not suitable for sufferers of fructose malabsorption, just as it is not appropriate for those with wheat allergies or celiac disease. However, some fructose malabsorbers do not have difficulty with fructans from wheat products while they may have problems with foods that contain excess free fructose.

There are many breads on the market that boast having no high fructose corn syrup. In lieu of high fructose corn syrup, however, one may find the production of special breads with a high inulin content, where inulin is a replacement in the baking process for the following: high fructose corn syrup, flour and fat. Because of the caloric reduction, lower fat content, dramatic fiber increase and prebiotic tendencies of the replacement inulin, these breads are considered a healthier alternative to traditionally prepared leavening breads. Though the touted health benefits may exist, sufferers of fructose malabsorption will likely find no difference between these new breads and traditionally prepared breads in alleviating their symptoms because inulin is a fructan, and, again, consumption of fructans should be reduced dramatically in those with fructose malabsorption in an effort to appease symptoms.

New research

Fructose and fructans which are polymers of fructose are FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo-, Di- and Mono-saccharides and Polyols) known to cause gastrointestinal discomfort in susceptible individuals. A low FODMAP diet has widespread application for managing functional gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS.[11]

See also

- Hereditary fructose intolerance

- FODMAP

- Gastroenterology

- Hydrogen breath test

- Invisible disability

- Food intolerance

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Malabsorption

References

- ↑ MayoClinic.com

- ↑ Ledochowski M, et al. (2001). "Fruktosemalabsorption" (PDF). Journal für Ernährungsmedizin (in German). 3 (1): 15–19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Berni Canani R, Pezzella V, Amoroso A, Cozzolino T, Di Scala C, Passariello A (Mar 10, 2016). "Diagnosing and Treating Intolerance to Carbohydrates in Children". Nutrients (Review). 8 (3): pii: E157. doi:10.3390/nu8030157. PMC 4808885

. PMID 26978392.

. PMID 26978392. - 1 2 3 Ebert K, Witt H (2016). "Fructose malabsorption". Mol Cell Pediatr (Review). 3 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s40348-016-0035-9. PMC 4755956

. PMID 26883354.

. PMID 26883354. - ↑ Putkonen L, Yao CK, Gibson PR (Jul 2013). "Fructose malabsorption syndrome". Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care (Review). 16 (4): 473–7. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e328361c556. PMID 23739630.

- ↑ http://www.uihealthcare.com/kxic/2008/06/fructose.html

- ↑ Montalto M, Gallo A, Ojetti V, Gasbarrini A (2013). "Fructose, trehalose and sorbitol malabsorption" (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (Review). 17 (Suppl 2): 26–9. PMID 24443064.

- ↑ Ledochowski M, Widner B, Murr C, Sperner-Unterweger B, Fuchs D (2001). "Fructose malabsorption is associated with decreased plasma tryptophan". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 36 (4): 367–71. doi:10.1080/003655201300051135. PMID 11336160.

- 1 2 Ledochowski M, Uberall F, Propst T, Fuchs D (1999). "Fructose malabsorption is associated with lower plasma folic acid concentrations in middle-aged subjects". Clin. Chem. 45 (11): 2013–4. PMID 10545075.

- ↑ Gibson PR, Newnham E, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG (2007). "Review article: fructose malabsorption and the bigger picture". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 25 (4): 349–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03186.x. PMID 17217453.

- 1 2 Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ (2010). "Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach". Advances in Clinical Practice. 25 (2): 252–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06149.x. PMID 20136989.

- ↑ http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/digestive-health/nutrition/BarrettArticle.pdf

- ↑ Skoog SM, Bharucha AE (2004). "Dietary fructose and gastrointestinal symptoms: a review" (PDF). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 99 (10): 2046–50. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40266.x. PMID 15447771.

- 1 2 3 4 Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR (2006). "Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: guidelines for effective dietary management" (PDF). Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 106 (10): 1631–9. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.010. PMID 17000196.

- ↑ USDA National Nutrient Database Release 20, September 2007

- ↑ Sugar Content of Selected Foods: Individual and Total Sugars Ruth H. Matthews, Pamela R. Pehrsson, and Mojgan Farhat-Sabet, (1987) U.S.D.A.

- ↑ "NUTTAB 2010 Online Searchable Database". Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 7 July 2013.