Freddy Maertens

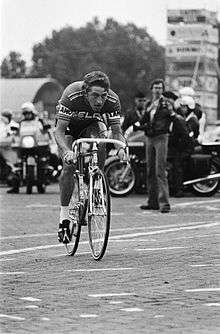

Maertens at the 1978 Tour de France | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Freddy Maertens | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

13 February 1952 Belgium | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current team | Retired | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Road | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Rider | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Rider type | Sprinter | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Professional team(s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1973–1979 | Flandria | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1980 | San Giacomo–Benotto | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1981-1982 | Boule d'Or-Colnago | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1983 | Masta - Concorde | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1984 | Splendor - Mondial Moquette | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1984 | AVP - Viditel | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1985 | Nikon - Van Schilt | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1985 | Euro-Soap - Crack | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1986 | Robland | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Major wins | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Freddy Maertens (born 13 February 1952 in Nieuwpoort) is a Belgian former professional racing cyclist who was twice world road race champion. His career coincided with the best years of another Belgian rider, Eddy Merckx, and supporters and reporters were split over which was the better.[1] Maertens' career swung between winning more than 50 races in a season to winning almost none and then back again. His life has been marked by debt and alcoholism.[1] It took him more than two decades to pay a tax debt.[1] He is now the curator of the Tour of Flanders museum in Oudenaarde.

Personal life

Maertens was the son of what his wife, Carine, described as a hard-working middle-class couple:[2] Gilbert Maertens and Silonne Verhaege. His mother was the daughter of a shipbuilder in Nieuwpoort harbour. She had a grocery and newspaper shop, which delivered newspapers. Gilbert Maertens, the son of a self-employed bill-sticker, was a flamboyant and restless man[1] who was a member of the local council and on the committee of the town football club. He ran a laundry with a staff of four behind his wife’s shop.

Maertens is one of four brothers: he, Mario, Luc and Marc. Marc also rode as a professional. Maertens went to the St-Bernadus college in Nieuwpoort. He read enthusiastically and showed a talent for languages. He could make himself understood in French, Italian and English as well as his native Dutch by the time he turned professional.[1] He then went to the Onze Lieve Vrouw [Holy Mother] college in Ostend.

Maertens and Carine Brouckaert met at a cycling club dance when she was 15. She had been sewing shoes for her father, a cobbler, since the previous year. The two were introduced by Jean-Pierre Monseré and his wife, Annie. Carine was Annie's niece. She had never heard of Maertens.[1]

They married in November 1973 and rented a house in Lombardsijde. She said: “I got to know a young boy who was more adult than his years and who knew what he wanted: to be a professional bike rider. I fell for him. Not because I thought he could become a great rider but because I felt straight away that I could play a role in his life, that he needed me. Three years later we were married. Our dream had started. We didn’t know then that it would turn into a nightmare.”[2]

Amateur career

Maertens rode his first race at Westhoek when he was 14, in 1966. The field included riders of 17 and 18, including some from France. The race was open to riders who did not have a licence from the Belgian federation, the BWB. He had trouble riding in a group. His second race went better. Among the riders he beat was Michel Pollentier, later a friend and a team colleague as a professional.

Maertens continued to ride unlicensed races in 1967. In 1968 he took his first licence from the BWB, riding in the nieuweling or beginners' class. He won 21 times and came second 19 times to a rider named Vandromme.[1]

Maertens asked his father permission to leave school in his second year as a junior, or under-19, rider. He won 64 times as a junior. His father made him promise that he would train regardless of the weather.

Relationship with father

Gilbert Maertens gave his son his first bike, which Freddy Maertens described as “a second-hand thing that he’d got from a beach business for a bargain.” Not until he won a race on that would he get a better one. The author, Rik Van Walleghem, said: “The training school that Maertens went through with his father was hard. Horribly hard. Gilbert never lost sight of anything. He knew how much and how often his son trained, what he ate and drank, how much he slept, who he went around with. He imposed a merciless regime. And he had an eye open for the slightest thing that would obstruct his son’s progress. He worried, for instance, that Freddy’s male hormones would get the better of his son and drive him into the arms of bewitching young girl who’d put the slides under his mission. Women were the devil’s work; it had been like that in the Garden of Eden and little had changed since.”[1]

Gilbert caught his son flirting with a girl and took revenge by cutting his racing bike in half.[1] He intervened with the army, when his son was called for national service, to ask that he not be given an easier time because of his reputation.

Maertens' relationship with his father affected the rest of his life. He rode well only when he had a dominant figure behind him: first his father, then Briek Schotte and then Lomme Driessens.[3] His wife described him as trusting and vulnerable, that he needed care because otherwise he would be “like a bird waiting for a cat.”[4]

Professional career

Maertens won 50 times as a senior, including the national championship at Nandrin. In 1970 he came second to the Frenchman, Régis Ovion, in the world amateur championship. He competed in the individual road race at the 1972 Summer Olympics.[5] He turned professional in 1972. The frame-maker Ernest Colnago and the former champion Ercole Baldini came to his house with an offer to join their SCIC team. They offered to support him in his last year as an amateur and then take him as a professional.

Gilbert Maertens was more impressed by the Belgian businessman, Paul Claeys, who had inherited the Flandria bicycle company. Flandria already sponsored Maertens' club, SWC Torhout, and Maertens rode a Flandria bike. Claeys came to the Maertens house with his team manager, Briek Schotte, a legend in Belgian cycling. Claeys offered Gilbert Maertens a concession for Flandria bikes, allowing him to sell them without first buying them. Maertens pushed his son to sign a contract for 40,000 francs a month as an amateur and then double in his first full year as a professional. The family needed the bike concession because Silonne Maertens had fallen ill and closed her shop.

Maertens said: "I would have preferred to go to SCIC and Colnago but my father said, 'You have to do something for us too.'"[3]

Colnago and Baldini had promised more money and a gentle start as a professional. But with Flandria Maertens rode more than 200 road races a year and on the track and in cyclo-cross in the winter.[6] He suffered what he called the poor organisation and penny-pinching attitude of Claeys and his Flandria company.[1] He also complained about the weight of Flandria frames; rather than ride them, he had his frames made in Italy, by Gios Torini, and had them painted in Flandria colours.[3]

He was never paid in 1979, his last season with Flandria, which had failed.[7] It was the start of financial troubles with tax officials (see below).

Rik Van Wallaghem says Maertens' was naïve as a new professional. Belgian racing was dominated by Eddy Merckx and Roger De Vlaeminck. Maertens did not observe an unwritten rule that new professionals establish themselves gradually and not try to humiliate established riders. Instead, Maertens, just 21, charged in and upset everyone by demanding they make room for him and make room quickly.”[1] What Van Wallaghem saw as his blunder was greeted, he said, by Belgian journalists eager to write of something else after years of Merckx's international domination. That worsened relations between them.

1973 world championship

Relations between the riders and their fans reached their nadir on 2 September 1973 in the world road championship around the Montjuich climb near Barcelona. Maertens had said he was not willing to ride for Merckx. That angered Merckx's supporters who, Maertens said, six times threw cold water over his legs.[8]

Merckx broke clear on a hill. Maertens said none of the others took up the chase and so he chased by himself. Merckx was angry that Maertens, in his view, had sabotaged his chances of winning. Maertens was the better sprinter.

The two were unable to cooperate and were caught by Luis Ocaña and Felice Gimondi. Maertens agreed to lead Merckx in the sprint and allow him to win. He would be well paid, he understood - "a fantastic offer."[8] But Maertens rode too fast for Merckx to stay with him. Gimondi rode in Maertens' shelter instead. Maertens realised too late and Gimondi won.

Enmity between Merckx and Maertens lasted decades. It ended in 2007 when the two met in a hotel in France.

"I was smoking a cigarette and he asked me for a cigarette. He said to me, 'Freddy, we have to talk about Barcelona.' I said, 'I think so too.' And then we spoke about it for three hours and we shook hands and everything was over.”[3]

Lomme Driessens

Guillaume “Lomme” Driessens was one of three father figures in Maertens' life (see above). He started as a masseur and soigneur for Fausto Coppi. Riders in his care won the Tour seven times. He was a team director from 1947 to 1984. He died in 2006.

Maertens said: “There was my father, then in the beginning as a professional I had Schotte, then I had Driessens...”[3] Driessens provoked the rivalry between Maertens and Merckx by insisting that far from Maertens' having betrayed Merckx by chasing him, Merckx had ensured that Maertens did not win. He had, he said, hidden his exhaustion and therefore his ability to win so as to mislead Maertens into losing.[9] The historian Olivier Dazat said Merckx had dropped Driessens as manager of his teams and that Driessens had never forgiven him.[10] Driessens had directed his Romeo-Smith team to ride all year against Rik van Looy in similar circumstances and now he wanted his revenge against Merckx.

Maertens said: "I enjoyed working with Driessens. There were no problems. When you work with Driessens there are no problems. A lot of people complained about Driessens, saying he took the racers’ money, that he did this, he did that. But in the morning, he was the first to wake you, he prepared your food. He was a fabulous organiser.” [3]

He was a dominant figure whose wish to control extended to standing over Carine Maertens to tell her she was not cooking minestrone correctly. Freddy Maertens said Driessens' visits and interventions meant they were no longer bosses in their own house.[11]

Equipment war

The world championship at Barcelona was complicated by commercial interests. Professional cycling had been dominated by an Italian component maker, Campagnolo. A Japanese rival, Shimano, had recently entered the market. It supplied the Flandria team and designed a range of components specifically for it.[9] Of the Belgian team, Maertens and Walter Godefroot used Shimano; Merckx and the others used Campagnolo.

The Belgian world championship team was training on the championship circuit two days before the race, along with some of the Italian team. Maertens said what he called the “big boss” [grand patron], since dead, at Campagnolo [named in his biography as Tullio Campagnolo] drove beside the group and shouted “Sort it out between you but Shimano mustn't be allowed to win the championship.”[9][12]

Maertens said Gimondi won because he pushed him into the barriers at the finish. When he demanded Belgian officials protest, he said, they answered: “We can't do that to our Italian friends.”[12]

1974 world championship

Maertens alleges that a laxative was put in his drink during the world championship in Montreal in 1974. He was handed it while he was in the lead with Bernard Thévenet and Constantino Conti. He said his masseur, Jef D’Hont, had told Gust Naessens - Merckx’s soigneur - that he was going to eat and asked him to hand a bottle to his rider. Maertens took the bottle because he trusted Naessens, with whom he worked from 1981 to 1983. Maertens said: “I got confirmation of that from Gust Naessens. I asked him, 'What did you do in Montreal?'" He said Naessens replied: “It was normal, Freddy. I was asked to give you your drink and I put something in it. You were too good for my guy, so I put something in it to block you.”[3][13][14] Merckx won.

Naessens, now dead, was also Tom Simpson's soigneur when he died in the Tour de France of 1967. The following year he was banned from working in cycling for two years.

1976 world championship

Maertens started favourite for the 1976 world championship, held at Ostuni, in Italy.[15] He came to the race in good form and with the Belgian team lined in his support.[3] His rival, Eddy Merckx, was in decline.[15]

The race was over hilly eight laps, a total of 288 km. The first moves came on the last lap. Yves Hézard attacked, followed by Francesco Moser and Joop Zoetemelk. Maertens made his move seven kilometres later, with Tino Conti. Maertens and Conti regained the leaders in seven kilometres. Moser attacked twice again and Maertens stayed with him. Zoetemelk and Conti lost ground. Moser realised he had no chance in a sprint with Maertens. The Belgian won by two lengths.

1977 Tour of Flanders

The Ronde van Vlaandren museum in Oudenaarde has in its window a lettered brick with the name of each year's winner. The 1977 race is shown as won by Roger De Vlaeminck. But above it is another, that reads: "Moral winner: Freddy Maertens."

Freddy Maertens was disqualified during the race after changing his bike on the Koppenberg hill. But he was not withdrawn from the race and he carried on riding with De Vlaeminck, a rival in another team. Maertens knew he could not win and he rode the last 80 km with De Vlaeminck in his shelter. Maertens says De Vlaeminck promised 300,000 francs, which De Vlaeminck denies. He says they never discussed money. Maertens says De Vlaeminck paid 150,000 francs, which Maertens gave to Michel Pollentier and Marc Demeyer for their help. Maertens expected a further 150,000 for his own services. De Vlaeminck says they never discussed money and the argument has never closed.[3]

Successes

Freddy Maertens often benefited by the help of his team-mates, Michel Pollentier and Marc Demeyer. They cleared a path through the bunch in the style of an earlier sprinter, Rik van Looy.[16] Journalists called them the Three Musketeers.

In 1976 he won eight stages of the Tour de France. He won the 'maillot vert in 1976 and again in 1978 and 1981.

1977 Vuelta

Maertens won the 1977 Vuelta a España by winning 13 stages, half the total. He imposed his will “like a South American dictator”, according to the writer Olivier Dazat.[16] He won the prologue time-trial and led the race from start to finish. 14 of the 20 stages were won by Flandria, with Pollentier taking the other stage win.

1977 Giro

Maertens again took the lead at the start by winning the prologue. He kept it until Francesco Moser became the race leader on stage five. Maertens was expected to take the lead again after Mugello, when there would be a time-trial. He had already won seven stages. The finish at Mugello ended in a crash. Michel Pollentier led Marc Demeyer into the last few hundred metres, with Maertens behind Demeyer. One by one they moved aside to let Maertens through. But he crashed, with Rik van Linden, and broke a wrist. He abandoned the race and the rest of the team would have returned to Belgium had Maertens not persuaded them otherwise.[17]

'''Wilderness years

There followed a wilderness period in which he did little of note. He started big races but often stopped after 100 km, or was dropped on unremarkable hills. It made his victory in the 1981 world championship in Prague the more remarkable. He finished in front of Giuseppe Saronni and Bernard Hinault, two short and stocky riders like himself. Journalists wondered whether the era of tall, lean riders such as Merckx, Gimondi, and De Vlaeminck was over.

A year later his record faded again. He rarely finished races and shone only in round-the-houses races, where his contract fees were needed to pay his tax debts. He did not defend his title in the 1982 world championship at Goodwood, saying he had injured his knee on a gate. He became fatter and rode for small teams for equally small salaries.

Olivier Dazat said: “His employers sacked him and others stepped in to benefit from the publicity. Freddy often forgot to go to races and was fired again. The press and those around him begged him to stop.”[16]

Other successes

As well as the Tour, Vuelta and Giro, his stage race victories included Paris–Nice (1977), the Four Days of Dunkirk (1973, 1975, 1976 and 1978), the Tour of Andalucia (1974, 1975), Tour of Belgium (1974, 1975), Tour de Luxembourg (1975), Tour of Sardinia (1977) and Vuelta y Catalunya (1977).

Despite his sprinting dominance, Maertens never won a one-day classic, coming closest with second places in the Tour of Flanders (1973) and Liège–Bastogne–Liège (1976). He was disqualified from second place in the 1977 Ronde after changing his bike on the Koppenberg climb.

Maertens also won the season-long Super Prestige Pernod International in 1976 and 1977.

1981 World Championship

In one of the most surprising comebacks in cycling history, Maertens won the 1981 World Championship, which was held in Prague. In a sprinting duel he had one ultimate jump left which sufficed to defeat runner-up Saronni.

Riding style

Maertens was an aggressive rider who pushed high gears. He frequently rode 53 x 13 or 14.[3] He was a talented time-triallist and an excellent sprinter. He nurtured another sprinter Sean Kelly. His time-trial record includes winning the Grand Prix des Nations in 1976.

Financial problems

Maertens and his wife were naïve about money.[1] Carine Maertens said money “flooded in” when her husband reached the top as a professional. Maertens estimated his earnings throughout his career as 10-15 million French francs, “which was a lot of money in the 1970s.”

Carine Maertens said: “We let ourselves be sweet-talked by sponsors, team directors, managers, architects, accountants, tax advisers, bankers, investment advisers, doctors. We believed all these people. We believed them because they dressed well and they’d been to school and they could talk well. We had no experience with money, fame, celebrity. We built far too large a villa, we borrowed money until we were raw, we invested in businesses we knew nothing about. We were honest people who trusted others, who never knew there was such nastiness in the world. By the time we realised what was happening, our bank accounts had been plundered. We had a chic villa and not a franc between us.”[18]

The Flandria team was riding the Giro d'Italia when it heard rumours of trouble at the Flandria company. He received only half his salary in 1978 and none of the cash to be paid without its being registered in the accounts.[3] In 1979, he was not paid at all. He lost money entrusted to others to invest, including 500 000 francs in the Flandria Ranch, run by his sponsor.[6] He also lost 750 000 francs in a furniture business which burned down.[6] By then he was being challenged by the tax authorities. He won little of significance. He said he was riding for nothing during the day and spending every evening with lawyers. He still disputes the tax that the government demanded. He and his wife lost their house, their car and their furniture.

He owed interest on interest and lost all he had. He calculated his tax bill at 30 million francs [almost US $1 million]. He insisted he owed 1.5 million francs [US $50,000]. He spent long periods without a job and without unemployment benefit and his wife cleaned houses. The problems lasted 30 years. They ended on 10 June 2011.[3] He felt so bitter about Paul Claeys - “not a good guy; he promised and promised and...” - that he refused to attend his funeral in 2012.[3]

Doping

Maertens told L'Équipe that "like everyone else", he had used amphetamines in round-the-houses races but he insisted that he had ridden without drugs in big Tours - not least because he knew he would be tested for them. He was angry when Belgian television used his photograph as a backdrop to discussions about drug-taking in the sport.[19]

Rumours intensified when Maertens' successes became erratic. He flew to the United States to see a doctor, to confirm that he had no drug problems. He and a medical advisers flew from Amsterdam to New York City on 25 May 1979 in a DC-10. Maertens mentioned to his colleague, Paul de Nijs, that one of the engines made an odd noise. The plane continued towards Chicago but crashed on take-off when an engine fell off, killing 279.[20][21]

Maertens was caught in drugs tests. He was first found positive after Professor Michel Debackere perfected a test in 1974 for pemoline, a drug in the amphetamine family that riders believed to be undetectable.[22]

He was disqualified in the Flèche Wallonne of 1977 and found guilty the same year in the Tour de France, the Tour of Belgium and the Tour of Flanders. He also had a positive finding for cortisone in 1986.[23]

Michel Pollentier is quoted as saying: "I told him I could see only one way out for him: to see a psychiatrist, advice he considered stupid. I’ve never hesitated to confess that I spent three weeks under the surveillance of Dr Dejonckheere at the St-Joseph clinic at Ostend and that after treatment I stayed under his control for another two years. Why hide it? It’s impossible to come out of a situation like that without the help of a doctor."[24]

Alcohol

Maertens drank champagne during races.[11] And he was for a while salesman for Lanson, a champagne company. Journalists saw crates of champagne at his house and interpreted them as confirmation that he had a drinking problem.

Legend says that on the Friday before the world championship at Goodwood, England, he asked his taxi driver to join him for a pint of beer, "because he sweating so much." Lomme Driessens said: "Too much wine and not enough riding, that's his problem."[11]

Maertens told a reporter, Guy Roger, that the stories were exaggerated. But he acknowledged later that he did have a problem. He attended meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous until word spread that he was there. Now he drinks only non-alcoholic drinks. His body, he said, reacted quickly to alcohol and he could get drunk on a single glass of beer.

Retirement

Maertens retired at the age of 35 in 1987 after deciding during a training ride that he no longer wanted to train in the wind and rain of Flanders.[25] He worked as a salesman after retiring, including in Belgium and Luxembourg for Assos, a Swiss clothing company. He left Assos, he said, when supplies became erratic. He kept a distance from the sport.[26] His weight rose to 100 kg. In 2000 he became curator of the Belgian national cycling museum in Roeselare. Visitors increased 11-fold the following year. He now works at the Centrum Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders Museum) in Oudenaarde.The bicycle shop "Maertens Sport" in Evergem on the outskirts of Ghent is owned by Freddy's brother Mario.

Major results

- 1971

- 1st

National Amateur Road Race Championship

- 2nd World Amateur Road Race Championships

- 1973

- 1st

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

- 1st Stage 5b

- 1st Scheldeprijs

- 2nd UCI World Road Race Championships

- 2nd Tour of Flanders

- 5th Paris–Roubaix

- 1974

- 1st

Overall Tour de Luxembourg

Overall Tour de Luxembourg

- 1st Stages 1 & 2

- 1st

Overall Vuelta a Andalucía

Overall Vuelta a Andalucía

- 1st Prologue a & b, Stages 1, 2, 4, 5 & 6

- 1st Kampioenschap van Vlaanderen

- 1st Stages 2, 3 & 4 Tour of Belgium

- 1st Stage 3b Four Days of Dunkirk

- 4th Amstel Gold Race

- 5th Paris–Tours

- 1975

- 1st

Overall Tour of Belgium

Overall Tour of Belgium

- 1st Stages 1b & 2

- 1st

Overall Vuelta a Andalucía

Overall Vuelta a Andalucía

- 1st Prologue, Stages 5, 6 & 7b

- 1st

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

- 1st Stage 3b

- 1st Paris–Tours

- 1st Paris–Brussels

- 1st Gent–Wevelgem

- Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

- 1st Prologue, Stages 1, 2a, 2b, 3, 4 & 7b

- 2nd Amstel Gold Race

- 3rd National Madison Championship (with Walter Godefroot)

- 4th Flèche Wallonne

- 5th Giro di Lombardia

- 5th Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 2

- 1976

- 1st

UCI World Road Race Championships

UCI World Road Race Championships - 1st

National Road Race Championships

- 1st

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

- 1st Stage 2b

- 1st Super Prestige Pernod International

- 1st Amstel Gold Race

- 1st Rund um den Henninger-Turm

- 1st Züri-Metzgete

- 1st Gent–Wevelgem

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Brabantse Pijl

- 1st Kampioenschap van Vlaanderen

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Michel Pollentier)

- 1st Critérium des As

- 1st Six Days of Dortmund (with Patrick Sercu)

- 2nd Liège–Bastogne–Liège

- 3rd La Flèche Wallonne

- 3rd National Madison Championship (with Marc Demeyer)

- 4th Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Prologue, Stages 2, 3, 4, 6a & 6b

- 5th Tour of Flanders

- 7th Overall Tour de Suisse

- 1st Points Classification

- 1st Prologue & Stage 1

- 8th Overall Tour de France

- 1st

Points classification

Points classification - 1st Prologue, Stages 1, 3, 7, 18a, 18b, 21 & 22a

- 1st

- 1977

- 1st

Overall Vuelta a España

Overall Vuelta a España

- 1st Points classification

- 1st Prologue, Stages 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11a, 11b, 13, 16 & 19

- Giro d'Italia

- 1st Prologue, Stages 1, 4, 6a, 6b, 7 & 8a

- 1st

Overall Paris–Nice

Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stages 1a, 1b, 2 & 7b

- 1st

Overall Volta Ciclista a Catalunya

Overall Volta Ciclista a Catalunya

- 1st Prologue, Stages 1, 3, 4 & 7a

- 1st

Overall Setmana Catalana de Ciclisme

Overall Setmana Catalana de Ciclisme

- 1st Stages 1, 4, 5a & 5b

- 1st

Overall Giro di Sardegna

Overall Giro di Sardegna

- 1st Stage 1

- 1st

National Derny Championship

- 1st Super Prestige Pernod International

- 1st Omloop Het Volk

- 1st Trofeo Laigueglia

- 1st Stage 1 Tour de Suisse

- 1st Six Days of Antwerp (with Patrick Sercu)

- 2nd National Omnium Championship

- 3rd Paris–Roubaix

- 3rd European Omnium Championship

- 5th Milan–San Remo

- 5th Liège–Bastogne–Liège

- 5th Amstel Gold Race

- 1978

- Tour de France

- 1st

Points classification

Points classification - 1st Stages 5 & 7

- 1st

- 1st

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

- 1st Stages 2a & 2b

- 1st Omloop Het Volk

- 1st E3 Prijs Vlaanderen

- 1st Tour du Haut Var

- 1st Stage 7a, Dauphiné Libéré

- 1st Six Days of Antwerp (with Danny Clark)

- 3rd European Omnium Championship

- 4th Paris–Roubaix

- 4th Amstel Gold Race

- 1st Stage 5 Tour de Suisse

- 1981

- 1st

UCI World Road Race Championships

UCI World Road Race Championships - Tour de France

- 1st

Points classification

Points classification - 1st Intermediate sprints classification

- 1st Stages 1a, 3, 12a, 13, & 22

- 1st

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Van Walleghem, Rik; Zwart-Wit (B) 2012

- 1 2 Maertens, Carine, in introduction to Van Walleghem, Rik; Zwart-Wit (B) 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Freddy Maertens interview". Bikeraceinfo.com. 2011-11-25. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ↑ Carine Maertens in Van Walleghem, Rik; Zwart-Wit (B) 2012

- ↑ "Freddy Maertens Olympic Results". sports-reference.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 Procycling, UK, issue 1

- ↑ L'Equipe, France, 9 July 2001

- 1 2 "Profiel: Wielrennen". Nrc.nl. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- 1 2 3 "Chocolate, Components and Conspiracy". Flandriabikes.com. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ↑ Dazat, Olivier (1987), Seigneurs et Forçats du Vélo, Calmann-Lévy, France

- 1 2 3 "de alternatieve bron voor sportnieuws". Sportgeschiedenis.nl. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- 1 2 L'Equipe, 9 July 2001

- ↑ "Histoire et Légende du cyclisme | Ensemble, partageons notre passion | Page 6". Legenducyclisme.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ↑ "Le lexique du dopage". cyclisme-dopage.com. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- 1 2 Chany, Pierre (1988) La Fabuleuse Histoire de Cyclisme, vol 2, Nathan, France

- 1 2 3 Dazat, Olivier (1987), Seigeneurs et Forçats de Vélo, Calmann-Lévy (France)

- ↑ "Red Tidal Wave: Domination". Flandriabikes.com. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ↑ Carine Maertens, introduction, Van Walleghem, Rik; Zwart-Wit (B) 2012

- ↑ Maertens, Freddy, Niet van Horen Zeggen (B)

- ↑ Maertens, Freddy, Niet van Horen Zeggen

- ↑ Young, David (1979-05-25). "The crash of American Airlines Flight 191 near O'Hare". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ↑ De Mondenard, Jean-Pierre (2003), Dopage: l'imposture des performances, Chiron (France)

- ↑ "L'annuaire du dopage". cyclisme-dopage.com. 1997-09-27. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ↑ Quoted Dazat, Olivier (1987), Seigneurs et Forcats du Velo, Calmann-Lévy, France

- ↑ L'Equipe magazine, 10 January 2004

- ↑ L'Equipe, France, 9 September 2001

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Freddy Maertens. |

- Freddy Maertens profile at Cycling Archives

- Official Tour de France results for Freddy Maertens

Further reading

"Fall From Grace" by Freddy Maertens and Manu Adriaens, ISBN 978-1-898111-00-9, 1993, Ronde Publications, Hull.