Frankenstein (1910 film)

| Frankenstein | |

|---|---|

_poster.jpg) Cover of a 1910 The Edison Kinetogram film catalog, featuring the first motion picture adaptation of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. | |

| Directed by | J. Searle Dawley |

| Written by | J. Searle Dawley |

| Based on |

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley |

| Starring |

Augustus Phillips Charles Ogle Mary Fuller |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Edison Manufacturing Company |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 14 minutes (975 feet) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent |

Frankenstein is a 1910 film made by Edison Studios. It was written and directed by J. Searle Dawley.[1]

This 16-minute short film was the first motion picture adaptation of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. The unbilled cast included Augustus Phillips as Dr. Frankenstein, Charles Ogle as Frankenstein's monster, and Mary Fuller as the doctor's fiancée.[2]

Plot

Described as "a liberal adaptation of Mrs. Shelley's famous story", the plot description in the Edison Kinetogram was:[3]

Frankenstein, a young student, is seen bidding his sweetheart and father goodbye, as he is leaving home to enter a college in order to study the sciences. Shortly after his arrival at college he becomes absorbed in the mysteries of life and death to the extent of forgetting practically everything else. His great ambition is to create a human being, and finally one night his dream is realized. He is convinced that he has found a way to create a most perfect human being that the world has ever seen. We see his experiment commence and the development of it. The formation of the hideous monster from the blazing chemicals of a huge cauldron in Frankenstein's laboratory is probably the most wierd, mystifying and fascinating scene ever shown on a film. To Frankenstein's horror, instead of creating a marvel of physical beauty and grace, there is unfolded before his eyes and before the audience an awful, ghastly, abhorrent monster. As he realizes what he has done Frankenstein rushes from the room, only to have the misshapen monster peer at him through the curtains of his bed. He falls fainting to the floor, where he is found by his servant, who revives him.The monster from the cover of the Edison KinetogramAfter a few weeks' illness, he returns home, a broken, weary man, but under the loving care of father and sweetheart he regains his health and strength and begins to take a less morbid view of life. In other words, the story of the film brings out the fact that the creation of the monster was only possible because Frankenstein had allowed his normal mind to be overcome by evil and unnatural thoughts. His marriage is soon to take place. But one evening, while sitting in his library, he chances to glance in the mirror before him and sees the reflection of the monster which has just opened the door of his room. All the terror of the past comes over him and, fearing lest his sweetheart should learn the truth, he bids the monster conceal himself behind the curtain while he hurriedly induces his sweetheart, who then comes in, to stay only a moment. Then follows a strong, dramatic scene. The monster, who is following his creator with the devotion of a dog, is insanely jealous of anyone else. He snatches from Frankenstein's coat the rose which his sweetheart has given him, and in the struggle throws Frankenstein to the floor, here the monster looks up and for the first time confronts his own reflection in the mirror. Appalled and horrified at his own image he flees in terror from the room. Not being able, howevers to live apart from his creator, he again comes to the house on the wedding night and, searching for the cause of his jealousy, goes into the bride's room. Frankenstein coming into the main room hears a shriek of terror, which is followed a moment after by his bride rushing in and falling in a faint at his feet. The monster then enters and after overpowering Frankenstein's feeble efforts by a slight exercise of his gigantic strength leaves the house.

Here comes the point which we have endeavored to bring out, namely: That when Frankenstein's love for his bride shall have attained full strength and freedom from impurity it will have such an effect upon his mind that the monster cannot exist. This theory is clearly demonstrated in the next and closing scene, which has probably never been surpassed in anything shown on the moving picutre screen. The monster, broken down by his unsuccessful attempts to be with his creator, enters the room, stands before a large mirror and holds out his arms entreatingly. Gradually, the real monster fades away, leaving only the image in the mirror. A moment later Frankenstein himself enters. As he stands directly before the mirror we are amazed to see the image of the monster reflected instead of Frankenstein's own. Gradually, however, under the effect of love and his better nature, the monster's image fades and Frankenstein sees himself in his young manhood in the mirror. His bride joins him, and the film ends with their embrace, Frankenstein's mind now being relieved of the awful horror and weight it has been laboring under for so long."

Production

Dawley, working for the Edison Company, shot the film in three days at the Edison Studios in the Bronx, New York City. The production was deliberately designed to de-emphasize the horrific aspects of the story and focus on the story's the mystical and psychological elements:[4]

In making the film the Edison Co. has carefully tried to eliminate all actual repulsive situations and to concentrate its endeavors upon the mystic and psychological problems that are to be found in this weird tale. Whenever, therefore, the film differs from the original story it is purely with the idea of elimination what would be repulsive to a moving picture audience.[5]

Music

Frankenstein was among the earlier silent films to have an associated cue sheet, providing suggested musical accompaniment.[6] From the cue sheet:[7][8]

At opening: Andante—"You Will Remember Me"

Till Frankenstein's laboratory: Moderato—"Melody in F"

Till monster is forming: Increasing agitato

Till monster appears over bed: Dramatic music from "Der Freischütz"

Till father and girl in sitting room: Moderato

Till Frankenstein returns home: Andante—"Annie Laurie"

Till monster enters Frankenstein's sitting room: Dramatic—"Der Freischütz"

Till girl enters with teapot: Andante—"Annie Laurie"

Till monster comes from behind curtains: Dramatic—"Der Freischütz"

Till wedding guests are leaving: Bridal Chorus from "Lohengrin"

Till monster appears: Dramatic—"Der Freischütz"

Till Frankenstein enters: Agitato

Till monster appears: Dramatic—"Der Freischütz"

Till monster vanishes into mirror: Diminishing Agitato

The pieces include "Then You'll Remember Me" from the 1843 opera The Bohemian Girl, the 1852 "Melody in F", "dramatic music" (presumably the "Wolf's Glen" scene) from the 1821 opera Der Freischütz, the 1835 song "Annie Laurie", and the Bridal Chorus from the 1850 opera Lohengrin.[9]

Copyright status

The film, just as all other motion pictures released before 1923, is now in the public domain, in the United States.

Rediscovery and preservation

For many years, this film was believed to be a lost film. In 1963, a plot description and stills (below) were discovered published in the March 15, 1910 issue the film catalog, The Edison Kinetogram.[10]

In the early 1950s, a print of this film was purchased by a Wisconsin film collector, Alois F. Dettlaff, from his mother-in-law, who also collected films.[11] He did not realize its rarity until many years later. Its existence was first revealed in the mid-1970s. Although somewhat deteriorated, the film was in viewable condition, complete with titles and tints as seen in 1910. Dettlaff had a 35 mm preservation copy made in the late 1970s. He also issued a DVD release of 1,000 copies.[12]

BearManor Media released the public domain film in a restored edition on March 18, 2010 alongside the novel, Edison's Frankenstein, which was written by Frederick C. Wiebel, Jr.[13]

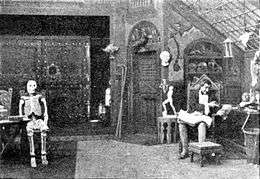

A still showing Charles Stanton Ogle as the monster. |

A still showing Augustus Phillips as Victor Frankenstein |

See also

- List of films featuring Frankenstein's monster

- List of American films of 1910

- List of rediscovered films

References

- ↑ New York Times

- ↑ Picart, Caroline Joan; Smoot, Frank; Blodgett, Jayne (2001). The Frankenstein Film Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-313-31350-9.

- ↑ Forest J., Ackerman, ed. (January 1964). "The Return of Frankens-ten". Famous Monsters of Filmland. No. 26. Philadelphia: Warren Publishing Co. p. 57.

- ↑ Laird, Karen (28 August 2015). The Art of Adapting Victorian Literature, 1848-1920: Dramatizing Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and The Woman in White. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-4724-2439-6.

- ↑ Edison Kinetogram. 2. 15 March 1910. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Boller, Paul F. (31 May 2013). Memoirs of an Obscure Professor. TCU Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-87565-557-4.

- ↑ Wierzbicki, James (21 January 2009). Film Music: A History. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-135-85143-9.

- ↑ Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey (1997). The Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-19-874242-5.

- ↑ Kalinak, Kathryn (1 May 2015). Sound: Dialogue, Music, and Effects. Rutgers University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8135-6428-9.

- ↑ Forest J., Ackerman, ed. (June 1963). "Frankenstein-1910!". Famous Monsters of Filmland. No. 23. Philadelphia: Warren Publishing Co. pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Loohauis, Jackie (18 March 1985). "Step Aside, Boris: Edison's Frankenstein was first". Green Sheet. The Milwaukee Journal. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2012-06-12.

- ↑ Jackie Loohauis, "A Horror Pioneer on Video", Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 28, 1997.

- ↑ Grove, Martin A. (12 March 2010). "'Frankenstein' breathes new life". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

Further reading

- Wiebel, Frederick C., Jr (25 December 2009). Edison's Frankenstein. Bear Manor Media. ISBN 1-59393-515-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frankenstein (film, 1910). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frankenstein (1910 film) |

- The short film Frankenstein is available for free download at the Internet Archive (alternative link)

- Frankenstein at the Internet Movie Database

- Frankenstein at AllMovie

- "Edison's Frankenstein: Cinema's First Horror Film" by Rich Drees

- Film Threat essay on the film's history