Frank Auerbach

Frank Helmut Auerbach (born 29 April 1931) is a British painter. Born in Germany, he has been a naturalised British citizen since 1947.[1]

Life and career

Auerbach was born in Berlin, the son of Max Auerbach, a patent lawyer, and Charlotte Nora Burchardt, who had trained as an artist. Under the influence of the British writer Iris Origo, his parents sent him to Britain in 1939 under the Kindertransport scheme (although he has stated it was by private arrangement),[2] which brought almost 10,000 mainly Jewish children to Britain to escape from Nazi persecution.[3] Aged seven, Auerbach left Germany via Hamburg on 4 April 1939 and arrived at Southampton on 7 April.[4] Left behind in Germany, Auerbach's parents later died in a concentration camp in 1942.[5][6]

In Britain, Auerbach became a pupil at Bunce Court School, near Faversham in Kent, where he excelled in not only art but also drama classes. Indeed, he almost became an actor, even taking a small role in Peter Ustinov's play House of Regrets at the Unity Theatre in St Pancras, at the age of 17. But his interest in art proved a stronger draw and he began studying in London, first at St Martin's School of Art from 1948 to 1952, and at the Royal College of Art from 1952 to 1955. Yet, perhaps the clearest influence on his art training came from a series of additional art classes he took at London's Borough Polytechnic, where he and fellow St Martin's student Leon Kossoff were taught by David Bomberg from 1947 until 1953.[7]

From 1955, he began teaching in secondary schools, but quickly moved into the visiting tutor circuit at numerous art schools, including Ravensbourne, Ealing, Sidcup and the Slade School of Art. However, he was most frequently to be found teaching at Camberwell School of Art, where he taught from 1958 to 1965.[8]

Auerbach's first solo exhibition was at the Beaux Arts Gallery in London in 1956, followed by further solo shows at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1959, 1961, 1962 and 1963, and then at Marlborough Fine Art in London at regular intervals after 1965; at Marlborough Gallery, New York, in 1969, 1982, 1994, 1998 and 2006; and at Marlborough Graphics in 1990.[9]

In 1978, he was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London, and in 1986 he represented Britain in the Venice Biennale, sharing the biennale's main prize, the Golden Lion, with Sigmar Polke. Further exhibitions have included Eight Figurative Painters, held at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, USA, in 1981, alongside Michael Andrews, Francis Bacon, William Coldstream, Lucian Freud, Patrick George, Leon Kossoff and Euan Uglow; and a retrospective at the Kunstverein, Hamburg, in 1986, comprising paintings and drawings made between 1977 and 1985 originally shown at the 42nd Venice Biennale, also in 1986. This show then toured, with some additional works, to the Museum Folkwang, Essen, and the Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, in 1987. Exhibitions were also held at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, in 1989; the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, in 1991; and the National Gallery, London, in 1995.[10] He was included in the exhibition A New Spirit in Painting at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in 1981 and a solo exhibition of his paintings and drawings 1954 to 2001 was held there in 2001;[7] and held a solo show entitled Frank Auerbach Etchings and Drypoints 1954–2006 at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, which toured to the Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, during 2007–08; and another solo show at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, in 2009.[11]

Auerbach was the subject of a television film entitled Frank Auerbach: To the Studio (2001), directed by Hannah Rothschild and produced by Jake Auerbach (Jake Auerbach Films Ltd). This was first broadcast on the arts programme Omnibus on 10 November 2001.

David Bowie bought and owned Auerbach's "Head of Gerda Boehm" as part of his private collection. After Bowie's death in 2016, this piece was among many put up for auction in November 2016, where it was sold for £3.8 million (US $4.7 million).[12]

Style and influences

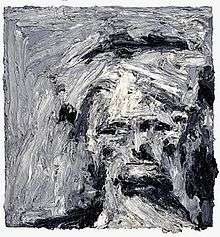

Auerbach is a figurative painter, who focuses on portraits and city scenes in and around the area of London in which he lives, Camden Town.[13] Although sometimes described as expressionistic,[14] Auerbach is not an expressionist painter. His work is not concerned with finding a visual equivalent to an emotional or spiritual state that characterised the expressionist movement, rather it deals with the attempt to resolve the experience of being in the world in paint. In this the experience of the world is seen as essentially chaotic with the role of the artist being to impose an order upon that chaos and record that order in the painting.[15] This ambition with the paintings results in Auerbach developing intense relationships with particular subjects, particularly the people he paints, but also the location of his cityscape subjects. Speaking on this in 2001 he stated: "If you pass something every day and it has a little character, it begins to intrigue you."[16] This simple statement belies the intensity of the relationship that develops between Auerbach and his subjects, which results in an astonishing desire to produce an image the artist considers 'right'. This leads Auerbach to paint an image and then scrape it off the canvas at the end of each day, repeating this process time and again, not primarily to create a layering of images but because of a sense of dissatisfaction with the image leading him to try to paint it again.[17]

This also indicates that the thick paint in Auerbach's work, which led to some of Auerbach's paintings in the 1950s being considered difficult to hang, partly due to their weight and according to some newspaper reports in case the paint fell off,[18] is not primarily the result of building up a lot of paint over time. It is in fact applied in a very short space of time, and may well be scraped off very soon after application.[16] This technique has not always been considered positively, with the Manchester Guardian newspaper commenting in 1956 that: "The technique is so fantastically obtrusive that it is some time before one penetrates to the intentions that should justify this grotesque method."[19]

This intensity of approach and handling has also not always sat well with the art world that developed in Britain from the late 1980s onwards, with one critic at that time, Stuart Morgan, denouncing Auerbach for espousing 'conservatism as if it were a religion' on the basis that he applies paint without a sense of irony.[20]

As well as painting street scenes close to his London home, Auerbach tends to paint a small number of people repeatedly, including Estella Olive West (indicated in painting titles as EOW), Juliet [21] Yardley Mills (or JYM) and Auerbach's wife Julia Auerbach (née Wolstenholme).[16] Again a similar obsession with specific subjects, and a desire to return to them to 'try again' is discernable in this use of the same models.

A strong emphasis in Auerbach's work is its relationship to the history of art. Showing at the National Gallery in London in 1994 he made direct reference to the gallery's collection of paintings by Rembrandt, Titian and Rubens. Unlike the National Gallery's 'Associate Artist Scheme', however, Auerbach's work after historic artists was not the result of a short residency at the National Gallery, it has a long history, and in this exhibition he showed paintings made after Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne, from the 1970s to Rubens's Samson and Delilah made in 1993.[22]

Auerbach's personal history, and his painting style, are the basis for the character "Max Ferber" in W. G. Sebald's award-winning novel, The Emigrants (1992 in Germany, 1996 in Britain)

Bibliography

- Frank Auerbach, William Feaver, Rizzoli International Publications (2009)

- Frank Auerbach, Robert Hughes, Thames & Hudson Ltd (1990)

- Frank Auerbach, British Council, The British Council Visual Arts Publications (1986)

- Frank Auerbach - Early Work 1954-1978, Paul Moorhouse, Offer Waterman & Co (2012)

- Frank Auerbach: The London Building Sites 1952-1962, Barnaby Wright (Author), Paul Moorhouse (Author), Margaret Garlake (Author), Paul Holberton Publishing (2010)

- Frank Auerbach: Paintings and Drawings 1954-2001, Catherine Lampert( Author), Norman Rosenthal (Author), Royal Academy of Arts (8 October 2001)

- Frank Auerbach, 'Fragments from a Conversation' [with Patrick Swift], 'X magazine', Vol. 1, No. 1 (November 1959); An Anthology from X, Oxford University Press (1988)

References

- ↑ Richard Morphet, The hard-won image (London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1984), p. 54

- ↑ BBC Radio 4 Front Row interview dated 4 October 2013

- ↑ Archived 26 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hughes, Robert (11 October 1990). "The Art of Frank Auerbach". The New York Review of Books. 37 (15). Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Eric L. Santner, On creaturely life: Rilke, Benjamin, Sebald (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), p. 100, note 2

- ↑ Jonathan Jones, "Frank Auerbach: a painter's painter of horrors and joy," The Guardian, 29 August 2014.

- 1 2 Catherine Lampert and Norman Rosenthal, Frank Auerbach: Paintings and Drawings 1954-2001 (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2001), p. 20

- ↑ Geoff Hassell, Camberwell School of Arts & Crafts: Its Students and Teachers 1943-1960 (Woodbridge: The Antique Collectors' Club, 1998), p. 31

- ↑ Barnaby Wright et al., Frank Auerbach: The London Building Sites 1952-1962 (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2010), p. 80

- ↑ Colin Wiggins, Frank Auerbach and the National Gallery (London: National Gallery Publications, 1995)

- ↑ Barnaby Wright et al., Frank Auerbach: The London Building Sites 1952-1962 (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2010), p. 80

- ↑ "Bowie Art Auction Nets $41 Million: Sotheby's". 13 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ 'Art View' in The Economist, 3 February 2007

- ↑ Ben Lewis, 'Exuberant unpredictability', in The Daily Telegraph (London newspaper), 30 April 2006. Also see John Gruen, 'Too Many Spooks', in New York Magazine, 13 October 1969, p. 54

- ↑ Richard Dorment, 'Heads above the rest', in The Daily Telegraph (London newspaper), 19 September 2001.

- 1 2 3 John O'Mahony, 'Surfaces and depths', in The Guardian (London newspaper), 15 September 2001

- ↑ Ben Lewis, 'Exuberant unpredictability', in The Daily Telegraph (London newspaper), 30 April 2006

- ↑ Moira Jeffrey, 'Still laying it on thick', in The Herald (Glasgow newspaper) 1 February 2002, p. 21

- ↑ Unsigned review, 'Large paintings in narrow confines,' in The Manchester Guardian (former British newspaper), 11 January 1956

- ↑ Stuart Morgan, 'Anglo-Saxon Attitudes', in Frieze Magazine, issue 21, March–April 1995

- ↑ Hannah Rothschild, 'Man of Many Layers', in Telegraph Magazine, 28 September 2013

- ↑ Tom Lubbock, 'After you, master, after you', The Independent (London), 1 August 1995

External links

- Frank Auerbach: To The Studio documentary (2001) Jake Auerbach Films

- Marlborough Art Gallery, artists' page

- BBC Radio 3 interview with Frank Auerbach