Franco-Ontarian

| Franco-Ontariens | |

|---|---|

Franco-Ontarian flag | |

|

| |

| Total population | |

| (1,700,000 Francophones, 2011)[1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Eastern Ontario, Northeastern Ontario | |

| Languages | |

| Canadian French, Canadian English | |

| Religion | |

| predominantly Christian (Roman Catholicism, other denominations) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Franco-Manitobans, French Canadians, Québécois, Acadians, Cajuns, French Americans, Metis, French |

Franco-Ontarians (French: Franco-Ontariens or Franco-Ontariennes if female) are French Canadian or francophone residents of the Canadian province of Ontario. They are sometimes known as "Ontarois".

According to the 2006 Canadian census, there were 488,815 self-declared francophones in Ontario (declaring one mother tongue), comprising 4.1 per cent of the province's total population. A further 1,000,000 Ontarians self-declared French to be one of multiple mother tongues. According to the subsequent 2011 Canadian census, there were 493,300 self-declared francophones in Ontario (declaring one mother tongue) comprising 3.9% of the province's total population. There were 284,115 Ontarians who declared French as their home language, which represents only 2.2% of the population.[2] Franco-Ontarians constitute the largest French-speaking community in Canada outside of Quebec, as well as the largest minority language group within Ontario.

The francophone population is concentrated in Eastern Ontario, in Ottawa, Cornwall and many rural farming communities, and in Northeastern Ontario, in the cities of Sudbury, North Bay and Timmins and a number of smaller towns. Other communities with notable francophone populations are Lakeshore, Windsor, Penetanguishene and Welland. Most communities in Ontario have at least a few Franco-Ontarian residents.

Ottawa, with 128,620 francophones, has the province's largest Franco-Ontarian community by size. Among the province's major cities, Greater Sudbury, 29 per cent francophone, has the largest proportion of Franco-Ontarians to the general population, and Timmins, 41 per cent francophone, has the largest proportion among the smaller sized cities. Prescott and Russell United Counties has the highest proportion of Franco-Ontarians to the general population among the province's census divisions, with about two-thirds of the population being francophone.

Some smaller communities in Ontario have a francophone majority. These include Hearst, Kapuskasing, Smooth Rock Falls, Embrun, St. Charles, Sturgeon Falls, Rockland, Casselman, Dubreuilville, Vankleek Hill and Hawkesbury.

Early settlement

The French presence in Ontario dates from the mid-17th century. Early settlements in the region include the Mission of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons at Midland in 1649, Sault Sainte Marie in 1668, and Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit in 1701. Southern Ontario was part of the Pays d'en-haut (Upper Country) of New France and was later part of the province of Quebec until Quebec was split into The Canadas in 1791. However, prior to the Articles of Capitulation of Quebec, which handed control of New France from France to Great Britain, modern-day Ontario had only very limited European settlement, apart from a few military forts. Modern Franco-Ontarians are instead descended primarily from people who moved to Ontario from Quebec or New Brunswick in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Franco-Ontarian identity

The term Franco-Ontarian has two related usages which overlap closely but are not identical: it may refer to francophone residents of Ontario, regardless of their place of birth, or to people of French Canadian ancestry born in Ontario, regardless of their primary language or current place of residence.

In popular usage, the first meaning predominates and the second is poorly understood. Although most Franco-Ontarians meet both definitions, there are notable exceptions. For example, although Louise Charron was the first native-born Franco-Ontarian appointed to the bench of the Supreme Court of Canada, she was preceded as a francophone judge from Ontario by Louise Arbour, a Quebecer who worked in Ontario for much of her professional career as a lawyer and judge. As a result, both women have been referred to as "the first Franco-Ontarian Supreme Court justice", although the technically correct practice is to credit Charron, Franco-Ontarian in both senses, with that distinction.

Conversely, two of the most famous rock musicians from Ontario, Avril Lavigne and Alanis Morissette, are Franco-Ontarian by the second definition but not by the first, since they were born to Franco-Ontarian parents but currently live outside of Ontario and work primarily in English. Former Prime Minister Paul Martin was born in Windsor to a Franco-Ontarian father from Pembroke and an anglophone mother, although many Canadians consider him a Quebecer as he represented a Montreal riding in Parliament.

Both meanings can be politically charged. Using the second to the exclusion of the first may be considered offensive to some in that it excludes francophones born in or with ethnic origins from other countries, such as Haiti, Vietnam or Tunisia, from the Franco-Ontarian community. Using the first to the exclusion of the second obscures the very real ethno-cultural distinctions that exist between Franco-Ontarians, Québécois, Acadians, Métis and other Canadian francophone communities, and the pressures toward assimilation into the English Canadian majority that the community faces.

The Franco-Ontarian identity is further split into three groups according to historical waves of settlement and immigration. The first wave of settlement in the Detroit/Windsor area came in the 18th century, under French rule. Most settlers then came from what is now Quebec, including both full French and Métis. A second wave came in the 19th and early 20th centuries to the areas of Eastern Ontario and Northeastern Ontario. This was an immigration wave, in the sense that Ontario was primarily British and mainly English-speaking, but the migrants can also be considered settlers, because they founded many villages or settled within already existing francophone communities. In the Ottawa Valley, in particular, some families have moved back and forth across the Ottawa river for generations (the river is the border between Ontario and Quebec), which results in a complex borderland identity. In the city of Ottawa some areas such as Vanier and Orleans have a rich Francophone heritage, with families often having members on both sides of the Ottawa River.

The third and most recent wave consists of Quebecers and other francophones (Haitians, Maghrebans, Europeans, etc.) who move to the larger cities and often preserve their original identity (Québécois, Haitian, etc.) as their primary cultural affiliation. Franco-Ontarians may also have historical ties to more than one of these three groups, which blurs the lines between these distinctions. Intermarriage between Franco-Ontarians and people of other ethnic or cultural backgrounds is also quite common. As a result, the complex political and sociological context of Franco-Ontarian can only be fully understood by recognizing both meanings and understanding the distinctions between the two.

The term "Ontarois", following the convention that a francophone minority is referred to with ending of -ois, is sometimes used to distinguish French-speaking Ontarians, while the general term for Ontarian in French is Ontarien.

Government

Although Ontario as a whole is not officially bilingual, the Ontario government's French Language Services Act designates 25 areas of the province where provincial ministries and agencies are required to provide local French-language services to the public. An area is designated as a French service area if the francophone population is greater than 5,000 people or 10 per cent of the community's total population.

The French Language Services Act applies to provincial government services only. It does not require municipal governments to provide bilingual services. Municipal governments may, however, provide French language services at their own discretion.

The following census divisions (denoted in dark blue on the map) are designated areas in their entirety:

- Algoma District

- Cochrane District

- Greater Sudbury

- Hamilton

- Nipissing District

- Ottawa

- Prescott and Russell United Counties

- Sudbury District

- Timiskaming District

- Toronto

The following census divisions (denoted in light blue on the map) are not fully designated areas, but have communities within their borders which are designated for bilingual services:

- Chatham-Kent: Tilbury, Dover Township, Tilbury East Township

- Essex County: Lakeshore, Tecumseh, Windsor

- Frontenac County: Kingston

- Kenora District: Ignace

- Middlesex County: London

- Niagara Regional Municipality: Port Colborne, Welland

- Peel Region: Mississauga, Brampton

- Renfrew County: Laurentian Valley, Pembroke, Whitewater Region

- Simcoe County: Essa, Penetanguishene, Tiny

- Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry United Counties: Cornwall, North Glengarry, North Stormont, South Glengarry, South Stormont, Winchester

- Thunder Bay District: Greenstone, Manitouwadge, Marathon, Terrace Bay

The most recent addition to the list of designated areas is the city of Kingston. It was named in May 2006, and after the three-year implementation period provided for by the French Language Services Act, officially became a bilingual service centre in 2009.

The Office of Francophone Affairs is the government agency responsible for ensuring that French language services are provided. Francophones who live in non-designated areas can also receive French language services by directly contacting the Office of Francophone Affairs in Toronto, or in the nearest designated community. The cabinet minister currently responsible for the Office of Francophone Affairs is Madeleine Meilleur.

The judicial system in Ontario is officially bilingual in all areas, although in some parts of the province a legal matter involving francophones may have to be transferred to another region where francophone services are more readily available. A francophone who wishes to be served in French by the judicial system cannot be refused this transfer if he or she cannot be served locally in French.

There are 44 municipalities in Ontario which are officially or functionally bilingual at the municipal level. Most of these are members of the Francophone Association of Municipalities of Ontario, or AFMO.

On April 26, 2010, the Ontario government designated September 25 as Franco-Ontarian Day.[3] This date was chosen as it represented the anniversary of the official raising of the Franco-Ontarian flag in 1975.

Education

In the past, the Ontario government was often much less supportive of and often openly hostile toward the Franco-Ontarian community. Regulation 17, passed in 1912, forbade French-language instruction in Ontario schools. Although the regulation itself was rescinded in 1927, the government continued to refuse funding for French language high schools until the latter half of the 1960s. As a result, francophones had to pursue high school education in English, pay tuition to private high schools — which many Franco-Ontarian families could not afford — or simply stop attending school after Grade 9.[4]

As a result, several generations of Franco-Ontarians grew up without formal education since the dropout rate for francophones was quite high during this period. Franco-Ontarians thus opted for jobs which did not require reading and mathematical skills, such as mining and forestry, and were virtually absent from white collar jobs. Sociologically, it meant that education was not a value transmitted to younger Franco-Ontarians. Although this has changed dramatically since the advent of funding for francophone high schools in the 1960s, according to the 2001 census, francophones in Ontario still tend to have a lower level of education than the general population.

Further, those who do have higher levels of education often pursue job opportunities in larger cities, particularly Ottawa or even Montreal, which can create a barrier to economic development in their home communities. As well, even today many students of Franco-Ontarian background are still educated in anglophone schools. This has the effect of reducing the use of French as a first language in the province, and thereby limiting the growth of the Franco-Ontarian community; in the Canada 2006 Census, for example, 40 per cent of residents of Sudbury reported themselves as able to speak or understand French, but only 16 per cent of the city's population reported actually using the French language in their daily lives and barely one per cent of the city's population reported themselves as being exclusively francophone.

Ontario now has eight French-language Roman Catholic school boards and four French-language public school boards. Each of these school boards serves a significantly larger catchment area than an English-language school board in the province, due to the smaller francophone population.

Currently, Ontario has two exclusively francophone community colleges, La Cité collégiale in Ottawa, with a second campus in Hawkesbury, and Collège Boréal in Sudbury, with additional campuses in several Northern Ontario communities, and one in Toronto. Collège Boréal also operates a network of student access centres throughout the province to promote its programs and services. A third college, Collège des Grands-Lacs in Toronto, ceased operations in 2002, and its programs and services are now the Toronto campus of Collège Boréal. The Ontario Agricultural College has a francophone campus in Alfred.

Ontario has four universities which offer instruction in both English and French: Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Laurentian University in Sudbury, the Dominican University College in Ottawa, and the University of Ottawa. York University in Toronto has a bilingual federated college, Glendon College, although the university is otherwise an anglophone institution. Laurentian University has a federated college, Université de Hearst, which, although not a fully independent university, is the only exclusively francophone university-level institution in the province. In 2015, MPP France Gélinas introduced a private member's bill to mandate the creation of a fully independent French-language university.[5]

Culture and media

The primary cultural organization of the Franco-Ontarian community is the Assemblée de la francophonie de l'Ontario, or AFO, which coordinates many of the community's cultural and political activities.

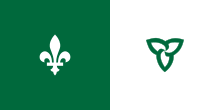

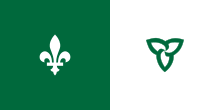

Franco-Ontarian flag

The Franco-Ontarian flag consists of two bands of green and white. The left portion has a solid light green background with a white fleur-de-lys in the middle, while the right portion has a solid white background with a stylized green trillium in the middle. The green represents the summer months, while the white represents the winter months. The trillium is the floral symbol of Ontario, while the fleur-de-lys represents the French-Canadian heritage of the Franco-Ontarian community. The green color on the flag is Pantone 349.

The flag was created in 1975 by Gaétan Gervais, history professor and Michel Dupuis, first year political science student, both from Laurentian University. It was officially recognized by the Ontario PC government as the emblem of the Franco-Ontarian community in the Franco-Ontarian Emblem Act of 2001.[6]

Ironically, in 2003 a controversy arose in Sudbury when the city government voted against flying the flag at Tom Davies Square for St-Jean-Baptiste Day, claiming that it would be inappropriate for the city government to display on public property a symbol representative of only a portion of the city's population. In 2006, new mayor John Rodriguez reversed that decision, permitting the flag to be flown, but was again criticized by some voters for acting unilaterally.

To commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Franco-Ontarian flag in September 2005, Prise de parole, a Sudbury-based publishing house, published a book titled Le Drapeau franco-ontarien (edited by Guy Gaudreau, a history professor at Laurentian University.)

On September 25, 2006, the largest Franco-Ontarian flag was unfurled in Ottawa.

Les Monuments de la francophonie d'Ottawa

The historical park, also known as Les Monuments de la francophonie d'Ottawa, was built by the francophone community to commemorate francophone contribution in the development and well being of the City of Ottawa. The first of six Monuments de la francophonie d'Ottawa designed by Edward J. Cuhaci represents the first homes and the founding of Bytown. The next five monuments, each progressing uphill, highlight business achievements that were crucial to the prosperity of Ottawa economy. The seventh monument, an unfinished granite block, symbolizes future developments.[7] The flag is 5 x 10 m and was raised on a 27 m pole.

Language

The dialects of French spoken in Ontario are similar to, but distinct from, Quebec French and constitute part of the greater Canadian French dialect. Due to the large English majority in the province, English loanwords are sometimes used in the informal or slang registers of Franco-Ontarian French. While English loanwords occur to a large extent in many varieties of French in Canada and Europe, there has been more of a conscious effort in Quebec to eliminate anglicisms.

In addition, the majority of Franco-Ontarians are, out of necessity, functionally or fluently bilingual in English — a fact that encourages borrowing, as does the fact that the English language has a greater prestige in the province due to its being a majority language. This means that Franco-Ontarian communities that have a small francophone population tend to have more English-influenced French, and some younger speakers there may feel more comfortable using English than French. On the other hand, the French spoken in French-dominant Ontarian communities (e.g., Hearst, Hawkesbury), or in those communities near the Quebec border (e.g., Ottawa), is virtually indistinguishable from Quebec French.

Furthermore, improved access to publicly funded French-language schools and the establishment of bilingual universities and French language community colleges has improved French language proficiency in younger populations. In addition, the French taught in Ontario French-medium schools is an international French, which allows educated speakers to use standard forms in formal situations where it would be more appropriate.

Folklore

Franco-Ontarians retain many cultural traditions from their French Canadian ancestry. For example, unmarried elder siblings dansent sur leurs bas (dance on their socks) when their younger siblings get married. Catholic Franco-Ontarians attend messe de minuit (midnight mass) on Christmas Eve. Many Franco-Ontarians also enjoy late night feasts/parties on Christmas Eve, called réveillon, at which tourtière is a common dish.

Media

Ontario has one francophone daily newspaper, Le Droit in Ottawa. However, 17 other communities in Ontario are served by francophone community weekly papers, including L'Express de Toronto, Le Voyageur in Sudbury, L'Action in London/Sarnia, Le Rempart in Windsor and Le Journal de Cornwall. Important historical publications include Sudbury's L'Ami du peuple, published from 1942 to 1968.

The province has two Radio-Canada television affiliates, CBOFT in Ottawa and CBLFT in Toronto, which have transmitters throughout the province. Both stations carry identical programming broadcast from Montreal, except for local news. CBOFT produces a newscast for broadcast only in the Ottawa area, while CBLFT produces another serving the rest of the province. The network formerly also operated CBEFT in Windsor, which was shut down in 2012. The provincial government operates TFO, which is available provincewide via cable and on the web. In 2003, TFO produced and aired Francoeur, the first Franco-Ontarian téléroman. In 2008, TFO also began airing the first Franco-Ontarian sitcom, Météo+ — itself, in part, a satire of the Franco-Ontarian community's relative lack of access to local French-language media. In 2012, the production team behind Météo+ launched Les Bleus de Ramville.

TVA, TV5 Québec Canada and RDI are available on all Ontario cable systems, as these channels are mandated by the CRTC for carriage by all Canadian cable operators. Where there is sufficient local demand for French-language television, Ontario cable systems may also offer French-language channels such as V, MusiquePlus and RDS, although these channels only have discretionary status outside of Quebec.

On radio, the Franco-Ontarian community is served primarily by Radio-Canada's Première Chaîne, which has originating stations in Ottawa (CBOF), Toronto (CJBC), Sudbury (CBON) and Windsor (CBEF), with rebroadcasters throughout Ontario. Espace musique, Radio-Canada's arts and culture network, currently broadcasts only in Ottawa (CBOX), Toronto (CJBC-FM), Sudbury (CBBX), Paris (CJBC-FM-1) and Windsor (CJBC-FM-2), with an additional transmitter licensed but not yet launched in Timmins.

Non-profit francophone community stations exist in several communities, including Penetanguishene (CFRH), Hearst (CINN), Kapuskasing (CKGN), Cornwall (CHOD), Ottawa (CJFO) and Toronto (CHOQ). Many campus radio stations air one or two hours per week of French-language programming as well, although only CHUO at the University of Ottawa and CKLU at Laurentian University are officially bilingual stations.

Francophone commercial radio stations exist in Sudbury (CHYC) and Timmins (CHYK); their owner, Le5 Communications, was licensed in 2011 to launch a third station in the Sturgeon Falls-North Bay area (CHYQ). The Timmins station also has rebroadcasters in Kapuskasing and Hearst, and a community group in Chapleau holds an independent license to rebroadcast the Sudbury station. Ottawa francophones are served by the commercial radio stations licensed to Gatineau, and many other Eastern Ontario communities are within the broadcast range of the Gatineau and Montreal media markets. One station in Hawkesbury (CHPR) airs a few hours per week of locally oriented programming, but otherwise simulcasts a commercial station from Montreal.

Film

Through their proximity to Gatineau or Montreal, Ottawa and the communities east of it toward Montreal are the only regions in Ontario which have regular access to French-language theatrical films. However, Cinéfest in Sudbury and the Toronto International Film Festival include francophone films in their annual festival programs, the Toronto-based Cinéfranco festival programs a lineup consisting entirely of francophone films, and community groups in many smaller communities offer French film screenings from time to time. Francophone films also air on TFO and Radio-Canada.

Theatre and music

Eight professional theatre companies offer French language theatrical productions, including four companies in Ottawa (Théâtre du Trillium, Théâtre de la Vieille 17, Vox Théâtre and Théâtre la Catapulte), one in Sudbury (Théâtre du Nouvel-Ontario) and three in Toronto (Théâtre Corpus, Théâtre La Tangente and Théâtre français de Toronto). There are also numerous community theatre groups and school theatre groups.

Annual music festivals include La Nuit sur l'étang in Sudbury and the Festival Franco-Ontarien in Ottawa. Notable figures in Franco-Ontarian music include Robert Paquette, Marcel Aymar, En Bref, Chuck Labelle, Les Chaizes Muzikales, Brasse-Camarade, Swing, Konflit dramatiK, Stéphane Paquette, Damien Robitaille and CANO.

The unofficial anthem of the Franco-Ontarian community is the song "Notre Place" by Paul Demers and François Dubé.

Publishing and literature

Ontario has seven francophone publishing companies, including Sudbury's Prise de parole, Ottawa's Editions Le Nordir and Les Éditions David.

Notable Franco-Ontarian writers include Lola Lemire Tostevin, Daniel Poliquin, Robert Dickson, Jean-Marc Dalpé, François Paré, Gaston Tremblay, Michel Bock, Doric Germain and Hédi Bouraoui. The French-language scholar Joseph Médard Carrière was Franco-Ontarian.

See also List of French Canadian writers from outside Quebec.

Political aspects

In the late 1980s, several Ontario towns and cities, most famously Sault Ste. Marie, were persuaded by the Alliance for the Preservation of English in Canada to declare themselves English-only in the wake of the French Language Services Act and the Meech Lake Accord debate. This was considered by many observers to be a direct contributor to the resurgence of the Quebec sovereignty movement in the 1990s, and consequently to the 1995 Quebec referendum. (See also Sault Ste. Marie language resolution.)

Quebec writer Yves Beauchemin once controversially referred to the Franco-Ontarian community as "warm corpses" (« cadavres encore chauds ») who had no chance of surviving as a community. In a similar vein, former Quebec Premier René Lévesque referred to them as "dead ducks".[8] However, the Canadian federal government has since provided significant financial assistance to Franco-Ontarian cultural groups and organizations, as it has chosen to assist in supporting and protecting French-language minority communities throughout Canada.

On October 19, 2004, a Toronto lawyer successfully challenged a "no left turn" traffic ticket on the basis that the sign was not bilingual in accordance with the 1986 French Language Services Act. The judge in R. v. Myers ruled that the traffic sign was not a municipal service, but instead was regulated under the provincial Highway Traffic Act and therefore subject to the bilingual requirements of the French Language Services Act.[9] As this was a lower court ruling, it did not affect any other court. However the implication of the decision was that many traffic signs in bilingually designated areas of Ontario would be invalid. It was feared that the ruling would have a similar effect as the Manitoba Language Rights ruling of the Supreme Court of Canada,[10] in this case forcing municipalities to erect new bilingual road signs at great expense and invalidating millions of dollars in existing tickets before the courts. The City of Toronto appealed the ruling. At the appeal hearing both parties asked the court to enter a plea of guilty. A guilty verdict was entered even though no arguments were made by either side on the merits of the case.[11] The situation created a legal vacuum for several years, during which numerous defendants used the bilingual signage argument to fight traffic tickets. The precedent was overturned by the Ontario Court of Appeal in a 2011 case, R. v. Petruzzo, on the grounds that the French Language Services Act specifically states that municipalities are not required to offer services in French, even in provincially regulated areas such as traffic signage, if the municipality has not specifically passed its own bylaw governing its own provision of bilingual services.[9]

Ontario's Minister of Francophone Affairs, Madeleine Meilleur, became the province's first cabinet minister to attend a Francophonie summit in 2004, travelling to Ouagadougou with counterparts from Quebec, New Brunswick and the federal government. Meilleur also expressed the hope that Ontario would someday become a permanent member of the organization. On November 26, 2016, Ontario was granted observer status by La Francophonie.[12]

On January 10, 2005, Clarence-Rockland became the first Ontario city to pass a bylaw requiring all new businesses to post signs in both official languages.[13] Clarence-Rockland is 60 per cent francophone, and the city council noted that the bylaw was intended to address the existence of both English-only and French-only commercial signage in the municipality.

In 2008, the provincial government officially introduced a French licence plate, with the French slogan "Tant à découvrir" in place of "Yours to Discover", as an optional feature for drivers who wished to use it.[14]

In 2009, the government faced controversy during the H1n1 flu pandemic, when it sent out a health information flyer in English only, with no French version published or distributed for the province's francophone residents.[15] In response, MPP France Gélinas introduced a private member's bill in May 2011 to have the provincial Commissioner of French Language Services report to the full Legislative Assembly of Ontario, rather than exclusively to the Minister of Francophone Affairs.[15]

Other notable Franco-Ontarians

See also

- French Canadian, Muskrat French

- Franco-Albertan, Franco-Columbian, Franco-Manitoban, Franco-Newfoundlander, Fransaskois, Franco-Ténois, Franco-Yukonnais

- English-speaking Quebecker

- List of francophone communities in Ontario

References

- ↑ 2011 Census Profile: Ontario

- ↑

- ↑ "September 25 Is Now Franco-Ontarian Day". Government of Ontario. April 26, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- ↑ C.M. Wallace and Ashley Thomson, Sudbury: Rail Town to Regional Capital. Dundurn Press, 1993. ISBN 1-55002-170-2.

- ↑ "Ontario needs a French university? Bien sûr, Gélinas says". Northern Life, May 26, 2015.

- ↑ Franco-Ontarian Emblem Act of 2001.

- ↑ Les Monuments de la francophonie d'Ottawa

- ↑ The Drama of Identity in Canada's Francophone West

- 1 2 "R. v. Petruzzo, 2011 ONCA 386 (CanLII)". CanLII, May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Manitoba Language Rights ruling

- ↑ 2005 CarswellOnt 10019

- ↑ http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/la-francophonie-observer-status-1.3869354

- ↑ Clarence-Rockland Bylaw 2005-12

- ↑ "Ontario Introduces French Licence Plate", May 30, 2008.

- 1 2 "New bill to change who French language commissioner reports to". Sudbury Star, May 30, 2011.

External links

- Government of Ontario, Office of Francophone Affairs

- Statistics (Government of Ontario, Office of Francophone Affairs)

- La fédération de la jeunesse franco-ontarienne (FESFO)

- Educational webpage about the 300-year-old French community near Windsor Ontario

- The Multicultural Canada website includes five historical Franco-Ontarian newspapers in full-text

- Festival franco-ontarien

- Centre franco-ontarien de folklore

- French-language education in Ontario