Francesco Zuccarelli

| Francesco Zuccarelli | |

|---|---|

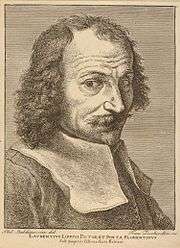

Portrait of Zuccarelli by Richard Wilson | |

| Born |

15 August 1702 Pitigliano |

| Died |

30 December 1788 (aged 86) Florence |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Late Baroque or Rococo |

Francesco Zuccarelli (formerly also Zuccherelli, Italian pronunciation: [franˈtʃesko dzukkaˈrɛlli], 15 August 1702 – 30 December 1788) RA, was an Italian painter of the late Baroque or Rococo period. He is considered to be the most important landscape painter to have emerged from his adopted city of Venice during the mid-eighteenth century,[1] and his Arcadian views became popular throughout Europe and especially in England where he resided for two extended periods. In 1768, Zuccarelli became a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts, and upon his final return to Italy, he was elected president of the Venetian Academy.

Rome and Tuscany (1702–32)

Born at Pitigliano, in southern Tuscany, Zuccarelli began his apprenticeship in Rome c. 1713–14 with the portrait painters Giovanni Maria Morandi (1622–1717) and his pupil Pietro Nelli (1672–1740), under whose tutelage he learned the elements of design while absorbing the lessons of Roman classicism.[3] Francesco completed his first commission in his hometown of Pitigliano in the years 1725–27, a pair of chapel altarpieces.[4] With the sponsorship of the Florentine art connoisseur, Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri (1676–1742), in the late 1720s and early 1730s Zuccarelli focused on etching. He eventually produced at least 43 prints, the majority consisting of two series which recorded the deteriorating frescoes of Giovanni da San Giovanni (1592–1636) and Andrea del Sarto (1486–1531).[5] During his period in Florence, though preoccupied with figurative subjects, he began to experiment with drawings in landscape,[6] and according to a non-contemporary source, his introduction to the latter genre was through the Roman landscape painter and etcher Paolo Anesi (1697–1773).[upper-alpha 1]

Venice and two stays in England (1732–71)

In 1732, after a stay of several months in Bologna, Zuccarelli relocated to Venice.[upper-alpha 2] Prior to his arrival in the Republic, the death of Marco Ricci in 1730 had created an opening in the field of landscape painting amid a marketplace crowded with history painters.[12] While continuing to paint religious and mythological works, he increasingly devoted his output to landscapes, drawing inspiration from the classicism of Claude and the Roman school.[13] His early paintings from the 1730s also show briefly the influence of Alessandro Magnasco, and for a longer period, of Ricci.[14] Zuccarelli brought a more mellow and airy palette to the typically Venetian colors, and using tonal values of higher luminous content than Ricci, the figures in his rural landscapes came alive.[15] The Tuscan scored an immediate success in Venice.[16] Zuccarelli enjoyed early patronage, from amongst others, Marshal Schulenburg; Consul Smith, who became his longtime patron; and Francesco Algarotti; who recommended him to the Elector of Saxony, Augustus III of Poland.[17] He often worked with other artists, including Bernardo Bellotto and Antonio Visentini.[17] In the mid–1740s, under the auspices of Consul Smith, he produced with Visentini a series featuring neo-Palladian architecture, as can be seen in Burlington House (1746).[18] Most charming of the Zuccarelli and Visentini collaborations is a set of 52 playing cards with Old Testament subjects published in Venice in 1748. The hand-colored scenes are treated in a light manner, the suit symbols are ingenious, and the cards begin with the creation of Adam and end with a battle scene that has an elephant carrying a castle.[upper-alpha 3] The outstanding achievement of his first Venetian period was a series of seven canvases, now located at Windsor Castle,[upper-alpha 4] which according to a note in an 18th century manuscript catalogue, represent the biblical characters of Rebecca with Jacob and Esau.[21][upper-alpha 5] The tall paintings are couched in a tender and dream-like poetic vein,[23] and most likely were originally situated at Consul Smith's villa at Mogliano.[24] He also occasionally created pastisches of various 17th-century Dutch masters.[upper-alpha 6] Towards 1750, when Zuccarelli reached his peak, his paint handling was very responsive to mood, bright with regard to color, thinly laid on and yet vibrantly effecti1ve.[23]

Francesco travelled to England to 1752, where his decorative talent resulted in diverse work, including the design of tapestries with the weaver Paul Saunders at Holkham Hall.[28] Around 1760 he drew from Shakespeare, depicting a scene from Macbeth where Macbeth and Banquo encounter the three witches, noteworthy as being one of the first paintings to portray theatrical characters in a landscape.[29] Zuccarelli held a sale of his canvases in 1762 at Prestage and Hobbs in London, before his departure for Italy.[30] In the same year, King George III acquired thirty of his works through the purchase of much of Consul Smith's extensive art collection and library in Venice.[31] In 1763 he became a member of the Venetian Academy,[32] but Zuccarelli was soon induced to journey back to London in 1765 by his friend Algarotti's bequest of a cameo and group of drawings made to Lord Chatham.[33] On this second visit to England, he was lauded by the English nobility and critics alike, and invited to exhibit at leading art societies;[34] moreover, King George III is said to have commissioned the out-sized painting River Landscape with the Finding of Moses (1768).[upper-alpha 7] Francesco Zuccarelli was a founding member, in 1768, of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Final years in Italy (1771–88)

Upon his return to Italy in 1771, Zuccarelli was soon afterward elected President of the Venetian Academy.[17] The work of his late maturity can broadly be characterized as "neo-riccian", for in this period the artist's style recalled the precision of his youthful emulation of Marco Ricci.[36] Francesco Zuccarelli eventually settled in Florence, and he died there in 1788.

Reputation and legacy

Francesco Zuccarelli was one of the few Venetian painters of his era to win universal acclaim, even from critics who rejected the concept of Arcadia. He was especially popular among the followers of Rousseau.[65] Francesco Maria Tassi (1716–1782), in his Lives of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects of Bergamo remarks that Zuccarelli paints "landscapes with the most charming figures and thus excels not only artists of modern times but rivals the great geniuses of the past; for no one previously knew how to combine the delights of an harmonious ground with figures gracefully posed and represented in the most natural colours".[66] With the move to more representational modes of depicting landscape in the 19th century, a reaction set in, and his works were to be the subject of the most disparaging invective.[67] A reappraisal of the artist began in 1959 with a decisive article by Michael Levey, Francesco Zuccarelli in England,[68] which helped explain the appeal of his works to his contemporaries by drawing a parallel with the affection of the 18th century English for pastoral poetry, since everyone could recognize a pleasing convention when they saw one; in this case, a fairyland where "the skies are forever blue, the trees forever green."[69] The exaltation of the rural life as a retreat from the noise of urbanity had the sanction of a long and distinguished history; as Levey writes, "Virgil had recommended it, Petrarch had practised it; Zuccarelli was left to illustrate it.[70] The last few decades have seen a resurgence of interest in Zuccarelli by Italian scholars, notably by Federico Dal Forno, who published an artistic biography with sixty paintings in 1994, and Federica Spadotto, who issued a catalogue raisonné in 2007. In a larger cultural context, modern historians have considered Zuccarelli to be a figure of interest with his love of escapism, seen as not untypical of the late Baroque.[23]

During the mid to late 18th century Francesco Zuccarelli was widely imitated, and artists influenced by him included Richard Wilson, Giuseppe Zais, Giovanni Battista Cimaroli, and Vittorio Amedeo Cignaroli.[73] Among those who created engravings after his work were Joseph Wagner, Fabio Berardi, Giovanni Volpato, Francesco Bartolozzi, and William Woollett.[74]

Identification of works

His paintings are rarely signed,[upper-alpha 9] yet they often contain a gourd water bottle that was held at the waist by rural Italian women, a punning allusion to his surname, zucco being the Italian word for gourd.[76] A defining touch found consistently across the long span of Francesco's career is a serene and vaguely sweet expression on the faces of his rounded figures.[77]

Selected paintings

- Saint Michael and the Devil; and The Holy Souls in Purgatory (1725–27) - Oil on canvas, 292 x 197 cm, Museo Civico, Pitigliano

- Landscape with a Castle; and Landscape with a Bridge (c. 1735) - Oil on canvas, 56 x 73 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- Landscape with River and Shepherds at Rest; and Landscape with Bridge and Knight (c. 1736) - Oil on canvas, 41 x 62 cm, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

- Landscape with Peasants at a Fountain (c. 1740) - Oil on canvas, 79.4 x 120.6 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Landscape with a Sleeping Child and a Woman Milking a Cow (early 1740s) - Oil on panel, 61 x 91.4 cm, Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh

- Landscape with a Wayside Tavern (early 1740s) - Oil on canvas, 82.6 x 113 cm, Hampton Court Palace, East Molesey, Surrey

- Landscape with a Woman fording a Stream on Horseback (c. 1742–43) - Oil on canvas, 36.8 x 50.2 cm, Windsor Castle, Windsor

- Roman Capriccio with Triumphal Arch, the Pyramid of Cestius, St. Peter's Basilica and the Castle of the Holy Angel (with Bernardo Bellotto, 1742–47) - Oil on canvas, 117 x 132 cm, Galleria nazionale, Parma

- Wooded Landscape with the Meeting of Isaac and Rebecca (1743) - Oil on canvas, 230 x 448 cm, Windsor Castle, Windsor[upper-alpha 10]

- Landscape with Jacob Watering Laban's Flock (1743) - Oil on canvas, 230.5 x 138.4 cm, Windsor Castle, Windsor

- Landscape with a Waterfall and Two Women with a Boy Fishing (1740–45) - Oil on canvas, 133.3 x 79.1 cm, Buckingham Palace, City of Westminster

- Bacchanal (c. 1745) - Oil on canvas, 142 x 210 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- The Banqueting Hall, Whitehall (with Antonio Visentini, 1746) - Oil on canvas, 84.1 x 128.9 cm, Windsor Castle, Windsor

- Silenus with Nymphs (1747) - Oil on canvas, 107 x 142 cm, Sanssouci, Potsdam

- Saint Jerome Emiliani with Orphans and the Virgin in Glory with Child (1748) - Oil on canvas, 270 x 181.5 cm, Pinacoteca Repossi, Chiari

- Portrait of Ercole Comini at Two Years (1751) - Oil on canvas, 51 x 41 cm, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

- Pastoral Scene (early 1750s) - Oil on canvas, 60 x 88 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

- Eastern Couple with Dromedary (c. 1756–58) - Oil on canvas, 180 x 130 cm, Palazzo Thiene, Vicenza

- Refreshment during the Ride (c. 1760) - Oil on canvas, 72 x 105 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

- Et in Arcadio Ego (1760) - Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 90.17 cm, collection Sir James Fergusson, London

- River Landscape with the Finding of Moses (1768) - Oil on canvas, 227.3 x 386 cm, Windsor Castle, Windsor

- Saint John the Baptist Preaching on the River Jordan (late 1760s) - Oil on canvas, 56 x 97 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

- Bull Hunting (early 1770s) - Oil on canvas, 114 x 150 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Banquet at a Villa (1770–1775) - Oil on canvas, 80 x 163 cm, Fondo Ambiente Italiano, Milan

Gallery

Landscape with the Penitent Magdalene. c. 1728. Drawing. British Museum.[upper-alpha 11]

Landscape with the Penitent Magdalene. c. 1728. Drawing. British Museum.[upper-alpha 11] Standing Female Figure Carrying a Lamp. Etching. Florence, 1728.[upper-alpha 12]

Standing Female Figure Carrying a Lamp. Etching. Florence, 1728.[upper-alpha 12]._Etching_by_Francesco_Zuccarelli._Published_by_Michele_Nestenus_and_Francesco_Mo%C3%BCcke._Florence%2C_1731..jpg) Il Malmantile Racquistato. Etching. Florence, 1731.[79]

Il Malmantile Racquistato. Etching. Florence, 1731.[79] Landscape with River and Shepherds at Rest. c. 1736. Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

Landscape with River and Shepherds at Rest. c. 1736. Accademia Carrara, Bergamo. Self-portrait. Drawing in chalks. 1736 or 1738. Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Self-portrait. Drawing in chalks. 1736 or 1738. Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Roman Capriccio with Triumphal Arch, the Pyramid of Cestius, St. Peter's Basilica and the Castle of the Holy Angel. Bernardo Bellotto and Francesco Zuccarelli. Mid–1740s. Galleria nazionale, Parma.

Roman Capriccio with Triumphal Arch, the Pyramid of Cestius, St. Peter's Basilica and the Castle of the Holy Angel. Bernardo Bellotto and Francesco Zuccarelli. Mid–1740s. Galleria nazionale, Parma.

Old Testament Playing Cards. Francesco Zuccarelli and Antonio Visentini. Venice, 1748. British Museum.[upper-alpha 13]

Old Testament Playing Cards. Francesco Zuccarelli and Antonio Visentini. Venice, 1748. British Museum.[upper-alpha 13] Margherita Tassi. 1751. Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

Margherita Tassi. 1751. Accademia Carrara, Bergamo. Pastoral Scene. Early 1750s. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Pastoral Scene. Early 1750s. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Eastern Couple with Dromedary. c. 1756–8. Palazzo Thiene, Vicenza.

Eastern Couple with Dromedary. c. 1756–8. Palazzo Thiene, Vicenza. Refreshment during the Ride. c. 1760. Fitzwilliam Museum, Glasgow.

Refreshment during the Ride. c. 1760. Fitzwilliam Museum, Glasgow. Landscape with the Story of Cadmus Killing the Dragon. Exhibited in 1765. Tate, London.[upper-alpha 14]

Landscape with the Story of Cadmus Killing the Dragon. Exhibited in 1765. Tate, London.[upper-alpha 14] Mountain Landscape with Washerwomen and a Fisherman. c. 1765–8. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[upper-alpha 15]

Mountain Landscape with Washerwomen and a Fisherman. c. 1765–8. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[upper-alpha 15] Seated female nude. By 1769. V&A Museum, London.[upper-alpha 16]

Seated female nude. By 1769. V&A Museum, London.[upper-alpha 16] River Landscape with the Finding of Moses. 1768. Windsor Castle, Windsor.

River Landscape with the Finding of Moses. 1768. Windsor Castle, Windsor. Bull Hunting. Early 1770s. Gallerie dell'Accademia,Venice.

Bull Hunting. Early 1770s. Gallerie dell'Accademia,Venice. The Zuccarelli Room in 1880, looking South West. Two landscapes by Zuccarelli are shown. Windsor Castle, Windsor.[upper-alpha 17]

The Zuccarelli Room in 1880, looking South West. Two landscapes by Zuccarelli are shown. Windsor Castle, Windsor.[upper-alpha 17] The Zuccarelli Room in 1880, looking South East. Three landscapes by Zuccarelli are shown. Windsor Castle, Windsor.[upper-alpha 18]

The Zuccarelli Room in 1880, looking South East. Three landscapes by Zuccarelli are shown. Windsor Castle, Windsor.[upper-alpha 18]

Footnotes

- ↑ Olivier cites Luigi Lanzi as the source which states Zuccarelli followed Anesi's lead in painting landscapes, but Olivier notes a certain hesitation in wording when comparing Lanzi's 1792 and 1795 editions.[7] However, it seems likely that Zuccarelli already knew Anesi from Rome, or met him in Florence via their common friend Franceso Maria Niccolò Gabburi, whose collection of paintings were devoted almost exclusively to landscape, and included five by Anesi, four from Ricci, and one of Claude. Both Zuccarelli and Anesi exhibited in Florence at the Academy of Design in 1729, held in the cloister of the basilica Santissima Annunziata, through Gabburi who had been a leading organizer of the event since 1705.[8][9]

- ↑ In Bologna, Zuccarelli published a book of prints dedicated to an unknown Florentine friend.[10] There is some disagreement about the timing and extent of Zuccarelli's movements from his Florentine period in the late 1720s to his arrival in Venice, which a few commentators date to 1730.[11]

- ↑ The cards are rather rare, and the set in the Collection of the United States Playing Card Company, in Cincinnati, Ohio, is of particular interest because the collection contains Zuccarelli's original drawings for the set. The medium is graphite, and Massar writes that the drawings exemplify Zuccarelli's soft, feathery touch.[19]

- ↑ With the exception of the painting Landscape with a Woman Wading in a Pond with Ducks, which was moved from Windsor Castle to Buckingham Palace.[20]

- ↑ Cust, in his introduction to the Italian List, stated that internal evidence indicates the catalogue was prepared by Consul Smith.[22]

- ↑ Levey writes of three works showing a mid-17th century Dutch influence in the Royal Collection. Landscape with a Wayside Tavern, (possibly a pastiche of Wouvermans), Hampton Court; Landscape with Ruins and Beggar, (a more obvious pastiche of Berchem), Windsor Castle; and Landscape with a Sleeping Child aa Woman Milking a Cow, noted in the Italian List[25] as being a pendant to a work formerly attributed to Rembrandt, and "in his stile [sic]," at Holyroodhouse.[26]

- ↑ The Crown also paid Zuccarelli ₤428.8s for 2 pictures and 2 frames on 12 January 1771, and Levey suggests the pictures may have been A Harbour Scene with Ruins, Figures and Cattle, and Landscape with a Temple and Cascade, both at Windsor Castle.[35]

- ↑ This watercolour by Charles Wild, with touches of bodycolour over pencil, was first published as an engraving in 1816 by Thomas Sutherland (1785–1838), in preparation for Pynes' The History of the Royal Residences. The paintings by Zuccarelli were laid on Mortlake tapestries of the Seasons, situated beneath a ceiling painted by Antonio Verrio (1636–1707), depicting the Assembly of the Gods. During renovations in the 1830s, Verrio's fresco was replaced by decorative plasterwork, and Zuccarelli's paintings were hung in different places, while the underlying tapestries were removed.[37][38] In 1854, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote, "I was charmed also by the nine landscapes of Zuccarelli, which adorn the state drawing room. Zuccarelli was a follower of Claude, and these pictures far exceed in effect any of Claude's I have yet seen."[39] The Zuccarelli Room stayed intact until around 1910, when it became a picture gallery with displays of other old masters, and the Italian's paintings were moved elsewhere.[40][41]

The following is a list of paintings by Francesco Zuccarelli formerly in the Queen's State Drawing Room. Note that the first seven paintings are identifiable in Wild's watercolour, starting from the left and continuing in sequence around the room to the right. The fifth canvas, Landscape with Two Young Children offering Fruit to a Woman, can be deduced in the 1816 view by its dimensions;[42][43] and that work, along with the last two pictures on the list, are featured in later photographs (see the Gallery section).- Landscape with Jacob Watering Laban's Flock[44][45]

- Hilly Landscape with two Children Fishing Watched by a Standing Woman and a Seated Man,[46][47] or alternatively, Jacob and Leah with their children Reuben and Simeon[48]

- River Landscape with Two Seated Women Embracing,[49][50] or alternatively, Jacob Leaving Haran for Canaan, right part (?)[51]

- Landscape with a Woman Wading in a Pond with Ducks,[52][50] or alternatively, Jacob Leaving Haran for Canaan, left part (?)[51]

- Landscape with Two Young Children offering Fruit to a Woman,[53][54] or alternatively, Rachel with two Children (or two Boys)[55]

- River Landscape with the Finding of Moses[56][57]

- River Landscape with a Woman Giving another Woman a Child to Suckle,[58][20] or alternatively, Bilhah and Zilpah with their Children[59]

- Wooded Landscape with the Meeting of Isaac and Rebecca,[60][61] or as suggested by Knox, The Meeting of Jacob and Laban[62]

- Landscape with a Groom and two Horses, and two Peasant Women[63][64]

- ↑ Spadotto's catalogue raisonné of 430 paintings only describes 26 with signatures.[75]

- ↑ In the first volume of his The History of the Royal Residences, Pyne in 1819 states "It was upon that picture [The Meeting of Isaac and Rebecca] that Zuccarelli rested his fame, and upon its reputation he found so much employment in England," and in addition, that "its composition is very superior" to the even larger The Finding of Moses. However, Levey qualifies Pyne by saying that his words shouldn't be taken very literally, as Zuccarelli had been well employed in England for at least ten years when the painting arrived, but it may well have attracted attention, if only due to its size.[78]

- ↑ Pen and brown ink with red chalk, and grey and brown wash, touched with white.

- ↑ After Giovanni da San Giovanni.

- ↑ A complete set of 52 playing cards, bequeathed by Lady Charlotte Guest in 1896, accompanied by the original leather case.

- ↑ Exhibited at the Free Society of Artists in 1765, and described by James Barry as an "exceedingly good landscape by Zuccarelli."[80]

- ↑ Gouache over black chalk, laid on modern paper.

- ↑ The drawing comes from one of two albums that belonged to the 18th century English architect, Richard Norris. The album is entitled, Sketches Taken in Italy 1769. Theodoli notes that drawings by Zuccarelli were much sought after by English collectors.[17] Charcoal and grey wash, heightened with white body-colour and red chalk, on cream paper.

- ↑ There are two large identifiable paintings by Zuccarelli. Seen from left to right: Wooded Landscape with the Meeting of Isaac and Rebecca,[81] and River Landscape with the Finding of Moses.[82] The photograph shows a Wyatville ceiling, and the paintings overlay wallpaper with a VR motif. Albumen photograph attributed to John Wesley Livingston (1835–1897). The image was commissioned by the Royal Collection for inventory purposes.[83]

- ↑ There are three identifiable paintings by Zuccarelli. Starting with the painting to the left of the fireplace, and continuing to the right: River Landscape with a Woman Giving another Woman a Child to Suckle;[84] Landscape with a Groom and two Horses, and two Peasant Women;[85] and Landscape with Two Young Children offering Fruit to a Woman.[86] Albumen photograph attributed to John Wesley Livingston (1835–1897).[87] For a wider view looking southeast, which shows more paintings by Zuccarelli, see The Royal Collection, RCIN 2935651.[88]

Notes

- ↑ Spadotto 2014, p. 115.

- ↑ Lippi 1731, p. 418.

- ↑ Tassi 1793, p. 86; Spadotto 2007, p. 10.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 10, 99.

- ↑ Massar 1998, pp. 247-263.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Lanzi 1792, p. 147; Lanzi 1795, p. 270; cited in Olivier 1996, p. 319.

- ↑ Olivier 1996, p. 333; Spadotto 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Perini 1998; vol. 51.

- ↑ Gabburi 1719–41, p. 1001; cited in Spadotto 2007, p. 379.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 12-15.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, p. 25.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 16-17, 21, 100-106.

- ↑ Zampetti 1971, pp. 109-110; Theodoli 1995, p. 169.

- ↑ Zampetti 1971, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Theodoli 1995, p. 169.

- ↑ Levey 1964, pp. 33, 104.

- ↑ Massar 1998, pp. 262-263.

- 1 2 Levey 1964, p. 106.

- ↑ Cust 1913, p. 153; Knox 1996, p. 37; Spadotto 2007, p. 112.

- ↑ Cust 1913, p. 152; Smith (?) c. 1770, cited by Cust 1913, pp. 153–154, 161–162.

- 1 2 3 Zampetti 1971, p. 110.

- ↑ Knox 1996, pp. 33-8.

- ↑ Cust 1913, p. 153.

- ↑ Levey 1964, p. 107.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 153-154.

- ↑ Levey 1959, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Levey 1959, pp. 6-8.

- ↑ Prestage and Hobbs 1762, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Cust 1913, p. 153; Levey 1959, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ West 2002, p. 715.

- ↑ Levey 1959, p. 11.

- ↑ Levey 1959, pp. 11-15.

- ↑ Anon. 1771, Georgian Papers in the Royal Archives at Windsor, no. 17253; cited by Levey 1964, p. 105.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, p. 41.

- ↑ "Windsor Castle: The Queen's Drawing Room". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 922102. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "The Picture Gallery, Windsor Castle". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 2935651. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Stowe 1854, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ "Windsor Castle: The Queen's Drawing Room". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 922102. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Ditchfield & Page 1923, pp. 29-56, Windsor castle: Architectural history; British History Online. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Smith (?) c. 1770, cited by Cust 1913, pp. 153–154, 161–162

- ↑ Levey 1964, pp. 105-107; Spadotto 2007, pp. 112-113.

- ↑ "Landscape with Jacob Watering Laban's flock". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 406008. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Levey 1964, p. 106; Knox 1996, pp. 34, 36; Spadotto 2007, pp. 112-113, 212.

- ↑ "Hilly Landscape with two Children Fishing Watched by a Standing Woman and a Seated Man". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 406009. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Levey 1964, p. 106; Spadotto 2007, pp. 112-113, 212.

- ↑ Knox 1996, pp. 35, 37.

- ↑ "River Landscape with Two Seated Women Embracing". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 405347. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- 1 2 Levey 1964, p. 106; Spadotto 2007, pp. 112-113, 211.

- 1 2 Knox 1996, p. 37.

- ↑ "Landscape with a Woman Wading in a Pond with Ducks". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 405938. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "Landscape with Two Young Children offering Fruit to a Woman". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 405329. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Levey 1964, pp. 105-106.

- ↑ Knox 1996, pp. 36-37; Spadotto 2007, pp. 112-113, 210.

- ↑ "River Landscape with the Finding of Moses". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 405358. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Pyne 1819, p. 115; Levey 1964, p. 107, plate 197; Spadotto 2007, pp. 167, 336.

- ↑ "River Landscape with a Woman Giving another Woman a Child to Suckle". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 404010. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Knox 1996, pp. 35-37; Spadotto 2007, pp. 112-113, 213.

- ↑ "Wooded Landscape with the Meeting of Isaac and Rebecca". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 401454. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Pyne 1819, p. 115; Levey 1964, p. 106; Spadotto 2007, p. 112-113, 210.

- ↑ Knox 1996, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ "Landscape with a Groom and two Horses, and two Peasant Women". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 401001. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Levey 1964, p. 106; Spadotto 2007, pp. 113, 213.

- ↑ Haskell 1986, p. 328.

- ↑ Tassi 1793; English translation cited by Zampetti 1971, p. 86

- ↑ Levey 1959, p. 1.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 48-49.

- ↑ Levey 1959, pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Levey 1959, p. 16.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, p. 152.

- ↑ "Pastoral Capriccio". ArtUK. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Dal Forno 1994, pp. 33-34; Spadotto 2009, pp. 326-328.

- ↑ Huber 1803, pp. 1163-1171.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 99-178.

- ↑ Edwards & Walpole 1808, p. 127.

- ↑ Spadotto 2007, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Pyne 1819, p. 115; Levey 1964, p. 106.

- ↑ Lippi 1731, frontispiece of vol. I.

- ↑ Levey 1959, p. 12.

- ↑ "Wooded Landscape with the Meeting of Isaac and Rebecca". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 401454. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "River Landscape with the Finding of Moses". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 405358. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "The Zuccarelli Room, Anno 1880, looking South West". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 2402779. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ↑ "River Landscape with a Woman Giving another Woman a Child to Suckle". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 404010. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "Landscape with a Groom and two Horses, and two Peasant Women". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 401001. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "Landscape with Two Young Children offering Fruit to a Woman". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 405329. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "The Zuccarelli Room, Anno 1880, looking South East". The Royal Collection. RCIN 2402780. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ↑ "The Picture Gallery, Windsor Castle". The Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 2935651. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

Sources

- Anon. (1771). Georgian Papers in the Royal Archives at Windsor (historical papers). Windsor Castle, Windsor.

- Cust, Lionel (1913). "Notes on Pictures in the Royal Collections–XXV" [The Italian List]. Burlington Magazine. XXIII.

- Dal Forno, Federico (1994). Francesco Zuccarelli pittore paesaggista del Settecento (in Italian). Verona: Centro per la formazione professionale grafica "San Zeno".

- Ditchfield, P. H.; Page, William, eds. (1923). "A History of the County of Berkshire". British History Online. London: Victoria County History. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- Edwards, Edward; Walpole, Horace (1808). Anecdotes of painters, who have resided or been born in England, with critical remarks on their productions. London: Leigh and Sotheby.

- Gabburi, Franceso Maria Niccolò (1719–41). Vite de' pittori (unpublished manuscript) (in Italian). Vol. II. Florence: Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale.

- Haskell, Francis (1986). Patrons and Painters: A Study in the Relations between Italian Art and Society in the Age of the Baroque (2nd ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02540-8.

- Huber, Michel (1803). Catalogue raisonné du cabinet d’estampes de feu Monsieur Winckler banquier et membre du sénat à Leipzig, contenant une collection des pieces anciennes et modernes de l’ecole italienne, dans une suite d’artistes depuis l’origine de l’art de graver jusqu’à nos jours (in French). Leipzig: Breitkopf et Härtel.

- Knox, George (June 1996). "Consul Smith's villa at Mogliano: Antonio Visentini and Francesco Zuccarelli". Apollo. CXLIII.

- Lanzi, Luigi (1792). La storia pittorica della Italia inferiore, o sia delle scuole fiorentina, senese, romana, napolitana (in Italian). Florence: A.G. Pagani.

- Lanzi, Luigi (1795). Storia pittorica della Italia dal Risorgimento delle Belle Arti fin presso la fine del XVIII secolo (in Italian). Bassano: Remondini.

- Levey, Michael (1959). "Francesco Zuccarelli in England". Italian Studies. XVI.

- Levey, Michael (1964). The Later Italian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen. London: Phaidon Press.

- Lippi, Lorenzo (pseud. Perione Zipoli) (1731). Il Malmantile Racquistato (in Italian). Florence: Michele Nestenus and Francesco Moucke.

- Massar, Phyllis Dearborn (September 1998). "The Prints of Francesco Zuccarelli". Print Quarterly. XV.

- Olivier, Michel (1996). "Recherches Biographiques sur Paolo Anesi". Vivre et Peindre à Rome au XVIIIe Siècle (in French). Rome: Palais Farnèse.

- Perini, Giovanni (1998). "Gabburi Francesco Maria Niccolò". Dizionario Biografico (in Italian). Trecanni, La Cultura Italiana. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- Prestage and Hobbs (1762). Pictures, of Mr. Zuccarelli, painted by himself, consisting of variety in landscapes, history. London.

- Pyne, William Henry (1819). The history of the royal residences of Windsor castle, St. James' palace, Carlton house, and Frogmore. Vol. I. London: A. Dry.

- Smith (?), Joseph (c. 1770). Catalogue of paintings of the Italian school, all in fine preservation, and in carved gilt frames in modern and elegant taste. Bought by His Majesty in Italy, and now chiefly at Kew. (Manuscript catalogue). Windsor Castle, Windsor.

- Spadotto, Federica (2007). Francesco Zuccarelli (in Italian). Milan: Bruno Alfieri. ISBN 978-88-902804-1-2.

- Spadotto, Federica (2009). "Zuccarelli tra emuli, imitatori e copisti". In Pedrocco, Filippo; Craievich, Alberto. L'impegno e la conoscenza: studi di storia dell'arte in onore di Egido Martina (in Italian). Verona: Scripta edizioni. ISBN 978-88-9616-213-2.

- Spadotto, Federica (2014). "Francesco Zuccarelli". Paesaggio veneti del '700 (in Italian). Minelliana. ISBN 978-88-6566-050-8.

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1854). Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands. Vol. II. London: Sampson, Lowe, Son & Co.

- Tassi, Francesco Maria (1793). Vite de' pittori, scultori e architetti bergamaschi (in Italian). Vol. II. Bergamo: Locatelli..

- Theodoli, Olimpia (1995). "Francesco Zuccarelli". In Martineau, Jane; Robison, Andrew. The Glory of Venice: Art in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300061864.

- "The Royal Collection". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- West, Shearer (2002). "Zuccarelli, Francesco". In Turner, Jane. Dictionary of Art. Vol. 33. New York: Grove. ISBN 9781884446009.

- Zampetti, Pietro (1971). "Zuccarelli Francesco". A Dictionary of Venetian Painters. Vol. 4. Leigh-On-Sea: F. Lewis. ISBN 9780853171812.

Further reading

- Pellegrino, Antonio Orlandi; Guarienti, Pietro (1753). Abecedario Pittorico del m.r.p (in Italian). Venice: G.B. Pasquali.

- Anon (1789). "Alcune Notìzie di Zuccarelli. Some Account of Zuccarelli". Mercurio Italico:o sia, Ragguaglio Generale intorno alla Letteratura, Belle Arti, Utili Scoperte, ec. di tutta l'Italia [obituary] (in Italian and English). London: Couchman & Fry.

- Angelo, Henry (1828). Reminiscences of Henry Angelo, with memoirs of his late father and friends, including numerous original anecdotes and curious traits of the most celebrated characters that have flourished during the last eighty years (Vol. 1). London: H. Colburn.

- Fabriziani, Giuseppe (1891). Giacomo Francesco Zuccarelli pittore 1702-1788: ricordo per messa novella: Pitigliano maggio 1891 (in Italian). Pitigliano: Tipografia Soldateschi.

- Rosa, Gilda (1945). Zuccarelli (in Italian). Milan: G.G. Gorlich.

- Levey, Michael (April 1959). "Wilson and Zuccarelli in England". Burlington Magazine. CI.

- Bettagno, Alessandro (1989). Francesco Zuccarelli, 1702–1788 : atti delle onoranze, Pitigliano (in Italian). Florence: Università Internazionale dell'Arte.

- Delneri, Anna (2003). "Il paesaggio arcadico di Francesco Zuccarelli". In Delneri, Anna; Succi, Dario. Da Canaletto a Zuccarelli (in Italian). Udine: Arti Grafiche Friulane Società Editrice. ISBN 8886550723.

- Spadotto, Federica (2016). Francesco Zuccarelli in Inghilterra: genesi di un capolavoro (in Italian). Verona: Cierre Grafica. ISBN 9788898768523.

External links

- Francesco Zuccarelli (1702–88) 14 works, Royal Collection, e-gallery.

- Francesco Zuccarelli paintings BBC Your Paintings (includes paintings attributed or associated with the artist)

- Francesco Zuccarelli (Italian Rococo Era Painter, 1702–1788) Artcyclopedia

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1900). "Zuccarelli, Francesco". Dictionary of National Biography. 63. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1900). "Zuccarelli, Francesco". Dictionary of National Biography. 63. London: Smith, Elder & Co. - "Alcume Notize di Zuccarelli. Some Account of Zuccarelli". (Obituary). In: Mercurio Italico:o sia, Ragguaglio Generale intorno alla Letteratura, Belle Arti, Utili Scoperte, ec. di tutta l'Italia. Couchman & Fry, 1789.

- Tassi, Francesco Maria; Vite de'pittori, scultori e architetti Bergamaschi; Locatelli; Bergamo, Italy. 1793. See pp. viii, xii, xiv, xv, 36. Francesco Maria Tassi was a long-time friend of Zuccarelli. The work was published posthumously.

- "Francis Zuccarelli, R.A." in Anecdotes of painters who have resided or been born in England : with critical remarks on their productions; by Edward Edwards, deceased, late teacher of perspective, and associate, in the Royal Academy; intended as a continuation to The anecdotes of painting by the late Horace Earl of Orford. Edward Edwards. London : printed by Luke Hansard & Sons, for Leigh and Sotheby, W.J. and J. Richardson, R. Faulder, T. Payne, and J. White, 1808.

- Lanzi, Luigi Antonio; Storia pittorica della Italia dal risorgimento delle belle arti fin presso al fine del XVIII secolo; Vol 1. Silvestre, Milan. 1823. First edition in 1795–6. See references to 'Zuccherelli' on pages 225, 246–7.

- "Francisco Zuccarelli, R.A." in Nollekens and His Times: Comprehending a Life of That Celebrated Sculptor; and Memoirs of Several Contemporary Artists, from the Time Of Roubiliac, Hogarth, and Reynolds, to that of Fuseli, Flaxman, and Blake. John Thomas Smith Keeper of the Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. Edited and annotated by Wilfred Whitten. Vol II. London: Henry Colburn, 1829.

Media related to Francesco Zuccarelli at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Francesco Zuccarelli at Wikimedia Commons