Four thieves vinegar

.jpg)

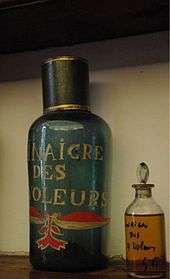

Four thieves vinegar (also called Marseilles vinegar, Marseilles remedy, prophylactic vinegar, vinegar of the four thieves, camphorated acetic acid, vinaigre des quatre voleurs and acetum quator furum[1][2]) is a concoction of vinegar (either from red wine, white wine, cider, or distilled white) infused with herbs, spices or garlic that was believed to protect users from the plague. The recipe for this vinegar has almost as many variations as its legend.

History

This specific vinegar composition is said to have been used during the medieval period when the black death was happening to prevent the catching of this dreaded disease.[3] Other similar types of herbal vinegars have been used as medicine since the time of Hippocrates.[4]

Early recipes for this vinegar called for a number of herbs to be added into a vinegar solution and left to steep for several days. The following vinegar recipe hung in the Museum of Paris in 1937, and is said to have been an original copy of the recipe posted on the walls of Marseilles during an episode of the plague:

Take three pints of strong white wine vinegar, add a handful of each of wormwood, meadowsweet, wild marjoram and sage, fifty cloves, two ounces of campanula roots, two ounces of angelic, rosemary and horehound and three large measures of champhor. Place the mixture in a container for fifteen days, strain and express then bottle. Use by rubbing it on the hands, ears and temples from time to time when approaching a plague victim.[3]

Plausible reasons for not contracting the plague was that the herbal concoction contained natural flea repellents, since the flea is the carrier for the plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis.[5] Wormwood has properties similar to cedar as an insect repellent, as do aromatics such as sage, cloves, camphor, rosemary, campanula, etc.[6] Meadowsweet, although known to contain salicyclic acid, is mainly used to mask odors like decomposing bodies.[7]

Another recipe called for dried rosemary, dried sage flowers, dried lavender flowers, fresh rue, camphor dissolved in spirit, sliced garlic, bruised cloves, and distilled wine vinegar.[8]

Modern day versions of four thieves vinegar include various herbs that typically include sage, lavender, thyme, and rosemary, along with garlic. Additional herbs sometimes include rue, mint, and wormwood. It has become traditional to use four herbs in the recipe—one for each thief, though earlier recipes often have a dozen herbs or more. It is still sold in Provence. In Italy a mixture called "seven thieves vinegar" is sold as a smelling salt, though its ingredients appear to be the same as in four thieves mixtures.[9]

Mythology

The usual story declares that a group of thieves during a European plague outbreak were robbing the dead or the sick. When they were caught, they offered to exchange their secret recipe, which had allowed them to commit the robberies without catching the disease, in exchange for leniency. Another version says that the thieves had already been caught before the outbreak and their sentence had been to bury dead plague victims; to survive this punishment, they created the vinegar. The city in which this happened is usually said to be Marseille or Toulouse, and the time period can be given as anywhere between the 14th and 18th century depending on the storyteller.[10]

One interesting twist says that "four thieves vinegar" is simply a corruption of the original "Forthave's vinegar," a popular concoction created by an enterprising fellow by the name of Richard Forthave.[10] Another source, the book Abregé de tout la médecine practique (published in 1741), seems to attribute its creation to George Bates, though Bates' own published recipe for antipestilential vinegar in his Pharmacopoeia Bateana does not specifically use the name 'thieves' or 'four thieves.'

References

- ↑ See Albert Allis Hopkins, The Scientific American Encyclopedia of Formulas: partly based upon the 28th ed. of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries (Munns & Co., Inc., 1910), 878; Henry Power & Leonard William Sedgwick, The New Sydenham Society’s Lexicon of Medicine and Allied Sciences (New Sydenham Society, 1881); Matthieu Joseph Bonaventure Orfila, Practical Chemistry; Or, A Description of the Processes by which the Various Articles of Chemical Research, in the Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Kingdoms, are Procured (Thomas Dobson and Son, at the Stone house, no. 41, South Second Street., 1818), 2; Thomas Byerley & John Timbs, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction; (Volume 12, 1828), 89; J.A. Paris, Pharmacologia (Volume 2, 1825), 18.

- ↑ Illes, Judika (2008). Magic When You Need It. Weiser Books. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-57863-419-4

- 1 2 Rene-Maurice Gattefosse, Gattefosse’s Aromatherapy (CW Daniel Company, Ltd. First published in Paris, France in 1937 by Girardot & Cie.), 85-86.

- ↑ http://www.apple-cider-vinegar-benefits.com/vinegar-history.html

- ↑ Yersinia pestis

- ↑ Wormwood

- ↑ Filipendula ulmaria

- ↑ Hopkins, The Scientific American Encyclopedia of Formulas, 1910, 878.

- ↑ http://www.cooker.net/doc/3A7B645D81D2CFB5C12572EE004D745A

- 1 2 Legend of Four Thieves Vinegar