Fortune-telling

Michail Alexandrowitsch Wrubel (1895)

Fortune-telling is the practice of predicting information about a person's life.[1] The scope of fortune-telling is in principle identical with the practice of divination. The difference is that divination is the term used for predictions considered part of a religious ritual, invoking deities or spirits, while the term fortune-telling implies a less serious or formal setting, even one of popular culture, where belief in occult workings behind the prediction is less prominent than the concept of suggestion, spiritual or practical advisory or affirmation.

Historically, fortune-telling grows out of folkloristic reception of Renaissance magic, specifically associated with Romani people.[1] During the 19th and 20th century, methods of divination from non-Western cultures, such as the I Ching, were also adopted as methods of fortune-telling in western popular culture.

An example of divination or fortune-telling as purely an item of pop culture, with little or no vestiges of belief in the occult, would be the Magic 8-Ball sold as a toy by Mattel, or Paul II, an octopus at the Sea Life Aquarium at Oberhausen used to predict the outcome of matches played by the German national football team.[2]

There is opposition to fortune-telling in Christianity, Islam and Judaism based on scriptural prohibitions against divination. This sometimes causes discord in the Jewish community due to their views on mysticism.

Terms for one who sees into the future include fortune-teller, crystal-gazer, spaewife, seer, soothsayer, sibyl, clairvoyant, and prophet; related terms which might include this among other abilities are oracle, augur, and visionary.

Methods

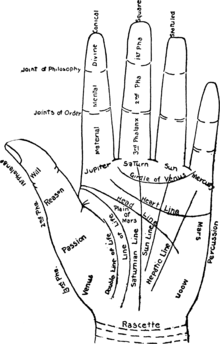

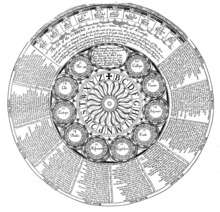

Common methods used for fortune telling in Europe and the Americas include astromancy, horary astrology, pendulum reading, spirit board reading, tasseography (reading tea leaves in a cup), cartomancy (fortune telling with cards), tarot reading, crystallomancy (reading of a crystal sphere), and chiromancy (palmistry, reading of the palms). The last three have traditional associations in the popular mind with the Roma and Sinti people (often called "gypsies").

Another form of fortune-telling, sometimes called "reading" or "spiritual consultation", does not rely on specific devices or methods, but rather the practitioner gives the client advice and predictions which are said to have come from spirits or in visions.

- Alectromancy: by observation of a rooster pecking at grain

- Astrology: by the movements of celestial bodies.

- Astromancy: by the stars.

- Augury: by the flight of birds.

- Bazi or four pillars: by hour, day, month, and year of birth.

- Bibliomancy: by books; frequently, but not always, religious texts.

- Cartomancy: by playing cards, tarot cards, or oracle cards.

- Ceromancy: by patterns in melting or dripping wax.

- Cheiromancy: by the shape of the hands and lines in the palms.

- Chronomancy: by determination of lucky and unlucky days.

- Clairvoyance: by spiritual vision or inner sight.

- Cleromancy: by casting of lots, or casting bones or stones.

- Cold reading: by using visual and aural clues.

- Crystallomancy: by crystal ball also called scrying.

- Extispicy: by the entrails of animals.

- Face reading: by means of variations in face and head shape.

- Feng shui: by earthen harmony.

- Gastromancy: by stomach-based ventriloquism (historically).

- Geomancy: by markings in the ground, sand, earth, or soil.

- Haruspicy: by the livers of sacrificed animals.

- Horary astrology: the astrology of the time the question was asked.

- Hydromancy: by water.

- I Ching divination: by yarrow stalks or coins and the I Ching.

- Kau cim by means of numbered bamboo sticks shaken from a tube.

- Lithomancy: by stones or gems.

- Necromancy: by the dead, or by spirits or souls of the dead.

- Numerology: by numbers.

- Oneiromancy: by dreams.

- Onomancy: by names.

- Palmistry: by lines and mounds on the hand.

- Parrot astrology: by parakeets picking up fortune cards

- Paper fortune teller: origami used in fortune-telling games

- Pendulum reading: by the movements of a suspended object.

- Pyromancy: by gazing into fire.

- Rhabdomancy: divination by rods.

- Runecasting or Runic divination: by runes.

- Scrying: by looking at or into reflective objects.

- Spirit board: by planchette or talking board.

- Taromancy: by a form of cartomancy using tarot cards.

- Tasseography or tasseomancy: by tea leaves or coffee grounds.

Sociology

Western fortune-tellers typically attempt predictions on matters such as future romantic, financial, and childbearing prospects. Many fortune-tellers will also give "character readings". These may use numerology, graphology, palmistry (if the subject is present), and astrology.

In contemporary Western culture, it appears that women consult fortune-tellers more than men.[3] Some women have maintained long relationships with their personal readers. Telephone consultations with psychics (at very high rates) grew in popularity through the 1990s but they have not replaced traditional methods.

As a business in North America

Discussing the role of fortune-telling in society, Ronald H. Isaacs, an American rabbi and author, opined, "Since time immemorial humans have longed to learn that which the future holds for them. Thus, in ancient civilization, and even today with fortune telling as a true profession, humankind continues to be curious about its future, both out of sheer curiosity as well as out of desire to better prepare for it."[4]

Popular media outlets like the New York Times have explained to their American readers that although 5000 years ago, soothsayers were prized advisers to the Assyrians, they lost respect and reverence during the rise of Reason in the 17th and 18th centuries.[5]

With the rise of commercialism, "the sale of occult practices [adapted to survive] in the larger society," according to sociologists Danny L. and Lin Jorgensen.[6] Ken Feingold, writer of "Interactive Art as Divination as a Vending Machine," stated that with the invention of money, fortune-telling became "a private service, a commodity within the marketplace".[7]

As J. Peder Zane wrote in the New York Times in 1994, "Whether it’s 3 P.M. or 3 A.M., there’s Dionne Warwick and her psychic friends selling advice on love, money and success. In a nation where the power of crystals and the likelihood that angels hover nearby prompt more contemplation than ridicule, it may not be surprising that one million people a year call Ms. Warwick’s friends." [5]

Clientele

In 1994, the psychic counsellor Rosanna Rogers of Cleveland, Ohio explained to J. Peder Zane that a wide variety of people consulted her: "Couch potatoes aren’t the only people seeking the counsel of psychics and astrologers. Clairvoyants have a booming business advising Philadelphia bankers, Hollywood lawyers and CEO’s of Fortune 500 companies... If people knew how many people, especially the very rich and powerful ones, went to psychics, their jaws would drop through the floor."[5] Ms. Rogers "claims to have 4,000 names in her rolodex."[5]

Typical clients

In 1982, Danny Jorgensen, a professor of Religious Studies at the University of South Florida offered a spiritual explanation for the popularity of fortune-telling. He said that people visit psychics or fortune-tellers to gain self-understanding,[8] and knowledge which will lead to personal power or success in some aspect of life.[9]

In 1995, Ken Feingold offered a different explanation for why people seek out fortune-tellers: "We desire to know other people’s actions and to resolve our own conflicts regarding decisions to be made and our participation in social groups and economies. […] Divination seems to have emerged from our knowing the inevitability of death. The idea is clear—we know that our time is limited and that we want things in our lives to happen in accord with our wishes. Realizing that our wishes have little power, we have sought technologies for gaining knowledge of the future… gain power over our own [lives]."[7]

Ultimately, the reasons a person consults a diviner or fortune teller are mediated by cultural expectations and by personal desires, and until a statistically rigorous study of the phenomenon has been conducted, the question of why people consult fortune-tellers is wide open for opinion-making.

Services

Traditional fortune-tellers vary in methodology, generally using techniques long established in their cultures and thus meeting the cultural expectations of their clientele.

In the United States and Canada, among clients of European ancestry, palmistry is popular[10] and, as with astrology and tarot card reading, advice is generally given about specific problems besetting the client.

Non-religious spiritual guidance may also be offered. An American clairvoyant by the name of Catherine Adams has written, "My philosophy is to teach and practice spiritual freedom, which means you have your own spiritual guidance, which I can help you get in touch with."[11]

In the African American community, where many people practice a form of folk magic called hoodoo or rootworking, a fortune telling session or "reading" for a client may be followed by practical guidance in spell-casting and Christian prayer, through a process called "magical coaching".[12]

In addition to sharing and explaining their visions, fortune-tellers can also act like counselors by discussing and offering advice about their clients' problems.[10] They want their clients to exercise their own willpower.[13]

Full-time careers

Some fortune-tellers support themselves entirely on their divination business; others hold down one or more jobs, and their second jobs may or may not relate to the occupation of divining. In 1982, Danny L., and Lin Jorgensen found that "while there is considerable variation among [these secondary] occupations, [part-time fortune-tellers] are over-represented in human service fields: counseling, social work, teaching, health care."[14] The same authors, making a limited survey of North American diviners, found that the majority of fortune-tellers are married with children, and a few claim graduate degrees.[15] "They attend movies, watch television, work at regular jobs, shop at K-Mart, sometimes eat at McDonald's, and go to the hospital when they are seriously ill."[16]

Legality

In 1982, the sociologists Danny L., and Lin Jorgensen found that, "when it is reasonable, [fortune-tellers] comply with local laws and purchase a business license."[14] However, in the United States, a variety of local and state laws restrict fortune-telling, require the licensing or bonding of fortune-tellers, or make necessary the use of terminology that avoids the term "fortune-teller" in favor of terms such as "spiritual advisor" or "psychic consultant." There are also laws that outright forbid the practice in certain districts.

For instance, fortune-telling is a class B misdemeanor in the state of New York. Under New York State law, S 165.35:

A person is guilty of fortune telling when, for a fee or compensation which he directly or indirectly solicits or receives, he claims or pretends to tell fortunes, or holds himself out as being able, by claimed or pretended use of occult powers, to answer questions or give advice on personal matters or to exercise, influence or affect evil spirits or curses; except that this section does not apply to a person who engages in the aforedescribed conduct as part of a show or exhibition solely for the purpose of entertainment or amusement.[17]

Law-makers who wrote this statute acknowledged that fortune-tellers do not restrict themselves to "a show or exhibition solely for the purpose of entertainment or amusement" and that people will continue to seek out fortune-tellers even though fortune-tellers operate in violation of the law.

Similarly, in New Zealand, Section 16 of the Summary Offences Act 1981 provides a one thousand dollar penalty for anyone who sets out to "deceive or pretend" for financial recompense that they possess telepathy or clairvoyance or acts as a medium for money through use of "fraudulent devices." As with the New York legislation cited above, however, it is not a criminal offence if it is solely intended for purposes of entertainment.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia also bans the practice outright, considering fortune-telling to be sorcery and thus contrary to Islamic teaching and jurisprudence. It has been punishable by death.[18]

Skepticism

Fortune-telling is dismissed by the scientific community and skeptics as being based on magical thinking and superstition.[19][20][21][22]

Skeptic Bergen Evans suggested that fortune-telling is the result of a "naïve selection of something that has happened from a mass of things that haven't, the clever interpretation of ambiguities, or a brazen announcement of the inevitable."[23] Other skeptics claim that fortune-telling is nothing more than cold reading.[24]

A large amount of fraud has occurred in the practice of fortune-telling.[25][26]

See also

- Divination in African traditional religion

- Divination in Chinese culture

- Prophecy

- Tengenjutsu (fortune telling)

Notes

- 1 2 Melton, J. Gordon. (2008). The Encyclopedia of Religious Phenomena. Visible Ink Press. pp. 115-116. ISBN 1-57859-209-7

- ↑ Associated Press6 July 2010

- ↑ Blécourt, Willem de; Usborne, Cornelle. (1999). Women's Medicine, Women's Culture: Abortion and Fortune-telling in Early Twentieth-Century Germany and the Netherlands. Medical History 43: 376-392.

- ↑ Isaacs, Ronald H. Divination, Magic, and Healing the Book of Jewish Folklore. Northvale N.J.: Jason Aronson, 1998. pg 55

- 1 2 3 4 (Zane 1994)

- ↑ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 376)

- 1 2 (Feingold 1995, p. 399)

- ↑ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 381)

- ↑ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 375)

- 1 2 "Clairvoyant or counsellor? Meet the woman who walks a fine line." The Northern Echo. 27 October 2000.

- ↑ Adams, Catherine. "What is Clairvoyance and What Can I Expect in a Session With Catherine?"

- ↑ "Magical Coaching and Spiritual Advice are among the ancillary services offered by some diviners and root doctors. These consultation services are usually engaged on an hourly basis." -- excerpt from an article on "magical coaching" at the Association of Independent Readers and Rootworkers web site

- ↑ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 384)

- 1 2 (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 377)

- ↑ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 337)

- ↑ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 387)

- ↑ Leginfo.state.ny.us

- ↑ Fortune Teller Faces Execution in Saudi Arabia pattayadailynews.com 1 April 2010 retrieved 17 July 2010

- ↑ Pronko, Nicholas Henry. (1969). Panorama of Psychology. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. p. 18

- ↑ Miller, Gale. (1978). Odd Jobs: The World of Deviant Work. Prentice-Hall. pp. 66-68

- ↑ Carroll, Robert Todd. (2003). "Divination (fortune telling)". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ↑ Regal, Brian. (2009). Pseudoscience: A Critical Encyclopedia. Greenwood. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-35507-3

- ↑ Evans, Bergen. (1955). The Spoor of Spooks: And Other Nonsense. Purnell. p. 16

- ↑ Cogan, Robert. (1998). Critical Thinking: Step by Step. University Press of America. p. 212. ISBN 0-7618-1067-6

- ↑ Boles, Jacqueline; Davis, Phillip; Tatro, Charlotte. (1983). False Pretense and Deviant Exploitation: Fortunetelling as a Con. Deviant Behavoir 4: 375–394.

- ↑ Steiner, Robert A. (1996). Fortunetelling. In Gordon Stein. The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 281-290. ISBN 1-57392-021-5

References

- Feingold, Ken (1995), "OU: Interactivity as Divination as Vending Machine", Leonardo, Third Annual New York Digital Salon, 28 (5): 399–402, doi:10.2307/1576224, JSTOR 1576224

- Hughes, M., Behanna, R; Signorella, M. (2001). Perceived Accuracy of Fortune Telling and Belief in the Paranormal. Journal of Social Psychology 141: 159-160.

- Jorgensen, Danny L.; Jorgensen, Lin (1982), "Social Meanings of the Occult", The Sociological Quarterly, 23 (3): 373–389, doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1982.tb01019.x.

- Zane, J. Peder (11 September 1994), "Soothsayers as Business Advisers; You Are Going to Go on a Long Trip…", The New York Times.

External links

![]() Media related to Fortune-telling at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fortune-telling at Wikimedia Commons