Fort Reno Park

| Fort Reno Park | |

|---|---|

|

A closeup of an 1865 map of Washington, D.C.'s defenses, showing the location of Fort Reno and other defenses to the northwest of Tenleytown. | |

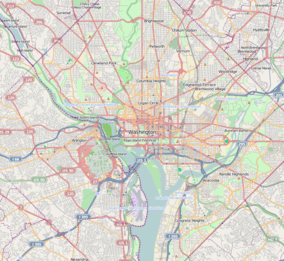

Location within Washington, D.C. | |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°57′07″N 77°04′33″W / 38.952°N 77.0759°WCoordinates: 38°57′07″N 77°04′33″W / 38.952°N 77.0759°W |

Fort Reno Park is a park in the Tenleytown neighborhood of Washington, D.C.. It is the highest point in the city,[1] and was involved in the only Civil War battle to take place in the District of Columbia. The highest natural elevation at Fort Reno, 409 feet (125 m),[1] is lower than the top of the Washington Monument, which rises 555 feet (169 m) from nearly sea level. The Highpointers Foundation is working with the National Park Service to place a sign near the USGS marker so that the highest natural point is easier to locate.

Construction

In early August 1861, engineers under Major John G. Barnard, in charge of the defenses of Washington, chose the highest point in the District of Columbia for the construction of a fort, with construction starting in earnest in August 1861 with the arrival of McCall's Division of Pennsylvania Reserves. The Utica Morning Herald (NY) of December 16, 1862 gives credit for the building of the fort specifically to the Ninth Regiment Pennsylvania Reserves, however it is known that other regiments of McCall's division were engaged in its construction and that of other forts in the vicinity. At the time the structure was named Fort Pennsylvania[2] and was only renamed Fort Reno in 1863 in honor of Major General Jesse Lee Reno who died at the Battle of South Mountain in 1862.[3]

It was one of a string of forts circling Washington to defend it against the Confederates. It had a perimeter of 517 yards, with places for 27 guns, and places for 22 field guns. It had one 100-pound Parrott gun.[3]

Work on the fort was continued by the succession of regiments stationed at the Tennallytown encampment after McCall's division moved to Langley on October 9, 1861. Of these regiments the 119th Pennsylvania is popularly given credit for having "built the fort"[4] in August and October 1862, however, Fort Pennsylvania had been worked on prior to the 119th Regiment's arrival by the regiments of Peck's Brigade (which were stationed at Tennallytown from October 1861 through to March 1862), the 59th New York and the 9th and 10th Rhode Island Regiments, amongst others. A large signal tower was also constructed at the fort during this period.[5] The location in the heights of North West D.C. was ideal for a signal tower, which likely would have relied on line-of-sight communications. Eventually the fort had a dozen heavy guns and a contingent of 3,000 men, making it the largest fort of those surrounding Washington.

Civil War Combat

The fort saw action on July 10–12, 1864, when Robert E. Lee sent 22,000 Confederates led by General Jubal A. Early against the 9,000 Union troops defending Washington (Ulysses S. Grant had depleted the Union defenses for his siege of Petersburg). The Confederates attacked from the north in Maryland. The initial warnings came from Fort Reno lookouts spying movement by Rockville. The attack itself was directed about 4 miles to the east across Rock Creek at Fort Stevens. The battle is known as "The Battle of Fort Stevens."

Following the war the fort became a "Freetown" for freed slaves and later a reservoir.

Cold War

During the Cold War, Continuity of Government (COG) installations were built at Fort Reno. The large brick circular tower, which appears to be a water tower, is actually a 50's-tech communications array, on top of living facilities for the crew. The tower was a part of a string of similar installations that connected the White House to "Site R" Raven Rock in Waynesboro,Pennsylvania.[6]

Park

Fort Reno is now maintained by the National Park Service, and includes a baseball field, several tennis courts, and large grass field areas. However the reservoir itself including the sandstone castle are off-limits to the public.

Residents gather here on the 4th of July to look down on the several annual fireworks displays over Montgomery County, Maryland and Northern Virginia that are visible from the western slope of the park.

Music Venue

Fort Reno's annual free summer concert series started in the Summer of 1968, amid social unrest following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.[7]

The 2014 series was the subject of drama, as the National Park Service suddenly demanded that organizers pay for US Park Police to be present at each concert. Unable to fund this position which was more than the entire budget for the concerts, organizers cancelled the concert series for the 2014 season.[8] The cancellation generated several news articles, Twitter outrage, a petition with 1,600 signers, and the ire of public officials who stepped in to pressure the agencies to swiftly issue the permit and meet with the concert organizer to resolve issues. After this meeting, the 2014 line-up was announced.[9]

On May 14, 2008 Fort Reno Park was closed due to the detection of arsenic in the soil, and a fence was erected around the park.[10] However, on May 28 the park was reopened and the fence removed after officials found that the initial high reading of arsenic levels was mistaken.[11]

See also

- Outline of District of Columbia

- Index of District of Columbia-related articles

- List of mountain peaks of the United States

- List of U.S. states by elevation

Notes

- 1 2 Dvorak, Petula. "D.C.'s Puny Peak Enough to Pump Up 'Highpointers'". The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ Officially named in Army Order No. 18, issued by Gen. McClellan on September 30, 1861.

- 1 2 Cooling III, Benjamin Franklin; Owen II, Walton H. (6 October 2009). Mr. Lincoln's Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington. Scarecrow Press. pp. 155–163. ISBN 978-0-8108-6307-1.

- ↑ Helm, J. B., 1981, Tenleytown, D.C. — Country village to city neighborhood, Washington, DC. p. 116

- ↑ http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008677142/

- ↑ http://greatergreaterwashington.org/post/8364/fort-renos-cold-war-era-undisclosed-location/

- ↑ Your Band Played Here - Washington City Paper

- ↑ Cooper, Rebeccca (June 26, 2014). "Fort Reno Concert Series Canceled in Dispute Over Permit". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ Ramanathan, Lavanya (June 30, 2014). "Rock on: Fort Reno will take place in 2014 after all". Washington Post. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ↑ High Arsenic Levels Found At Fort Reno Park in NW - washingtonpost.com

- ↑ National Park Service Will Reopen Fort Reno Park - Releases - District Department of the Environment

References

- Helm, J. B., 1981, Tenleytown, D.C. — Country village to city neighborhood, Washington, DC.