Floreana Island

| Native name: <span class="nickname" ">Santa María | |

|---|---|

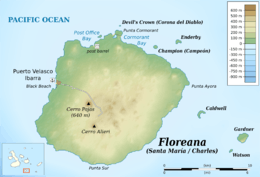

Map of Floreana | |

| Geography | |

| Location | East Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 1°17′51″S 90°26′03″W / 1.29750°S 90.43417°WCoordinates: 1°17′51″S 90°26′03″W / 1.29750°S 90.43417°W |

| Archipelago | Galápagos Islands |

| Area | 173 km2 (67 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 640 m (2,100 ft) |

| Highest point | Cerro Pajas |

| Administration | |

|

Ecuador | |

| Province | Claimed by: France (French city of Barcus) |

| Canton | San Cristóbal |

| Parish | Santa María |

| Largest settlement | Puerto Velasco Ibarra (pop. 100) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 100 |

| Pop. density | 0.6 /km2 (1.6 /sq mi) |

Floreana Island is an island of the Galápagos Islands. It was named after Juan José Flores, the first president of Ecuador, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelago. It was previously called Charles Island (after King Charles II of England), and Santa Maria after one of the caravels of Columbus.

The island has an area of 173 square kilometres (67 sq mi). It was formed by volcanic eruption. The island's highest point is Cerro Pajas at 640 metres (2,100 ft), which is also the highest point of the volcano like most of the smaller islands of Galápagos.

History

Since the 19th century, whalers kept a wooden barrel at Post Office Bay, so that mail could be picked up and delivered to their destination by ships on their way home, mainly to Europe and the United States. Cards and letters are still placed in the barrel without any postage. Visitors sift through the letters and cards in order to deliver them by hand.[1]

Due to its relatively flat surface, supply of fresh water as well as plants and animals, Floreana was a favorite stop for whalers and other visitors to the Galápagos. When still known as Charles Island in 1820, the island was set alight as a prank by helmsman Thomas Chappel from the Nantucket whaling ship the Essex. Being the height of the dry season, the fire soon burned out of control. The next day saw the island still burning as the ship sailed for the offshore grounds and after a full day of sailing the fire was still visible on the horizon.[2] Many years later Thomas Nickerson, who had been a cabin boy on the Essex, returned to Charles Island and found a black wasteland: "neither trees, shrubbery, nor grass have since appeared."[3] It is believed the fire contributed to the extinction of some species originally on the island.[3]

In September 1835 the second voyage of HMS Beagle brought Charles Darwin to Charles Island. The ship's crew was greeted by Nicholas Lawson, acting for the Governor of Galápagos, and at the prison colony Darwin was told that tortoises differed in the shape of the shells from island to island, but this was not obvious on the islands he visited and he did not bother collecting their shells. He industriously collected all the animals, plants, insects and reptiles, and speculated about finding "from future comparison to what district or 'centre of creation' the organized beings of this archipelago must be attached."[4][5]

In 1929, Friedrich Ritter and Dore Strauch arrived in Guayaquil from Berlin to settle on Floreana, and sent letters back that were widely reported in the press, encouraging others to follow. In 1932 Heinz and Margret Wittmer arrived with their son Harry, and shortly afterwards their son Rolf was born there, the first citizen of the island known to have been born in the Galápagos. Later in 1932, the self-described "Baroness" von Wagner Bosquet arrived with companions, but a series of strange disappearances and deaths (including possible murders) and the departure of Strauch left the Wittmers as the sole remaining inhabitants of the group who had settled there. They set up a hotel which is still managed by their descendants, and Mrs. Wittmer wrote an account of her experiences in her book Floreana: A Woman's Pilgrimage to the Galápagos.[6][7] A documentary film recounting these events, The Galapagos Affair, was released in 2013.[8]

The demands of these visitors, early settlers, and introduced species devastated much of the local wildlife with the endemic Floreana tortoise being declared extinct[9] and the endemic Floreana mockingbird becoming extirpated on the island (the few remaining are found on the nearby islands of Gardiner and Champion).[10]

When Charles Darwin visited the island in 1835, he found no sign of its native tortoise and assumed that whalers, pirates, and human settlers had wiped them out. Since about 1850, no tortoises have been found on the island (except for one or two introduced animals kept as pets by the locals), and the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the Floreana tortoise (Chelonoidis elephantopus sometimes called Chelonoidis nigra) as extinct.[11] However, it may be that there are pure Floreana tortoises living on other islands in the archipelago.[11][12][13]

Points of interest

- A favorite dive and snorkeling site, “Devil's Crown”, located off the northeast point of the island, is an underwater volcanic cone, offering the opportunity to snorkel with schools of fish, sea turtles, sharks and sea lions, which are abundant amongst the many coral formations found here.

- At Punta Cormorant, there is a green olivine beach to see sea lions and a short walk past a lagoon to see flamingos, rays, sea turtles, and Grapsus grapsus (Sally Lightfoot) crabs. Pink flamingos and green sea turtles nest from December to May on this island. The "joint footed" petrel is found here, a nocturnal sea bird which spends most of its life away from land.

- Post Office Bay provides visitors the opportunity to send post cards home without a stamp via the over 200-year-old post barrel and other travelers.

- A miniature football (soccer) field, complete with goals, at the end of Post Office Bay, is used by tour boat crews and their tourists.

Gallery

Floreana Island

Floreana Island Post Barrel

Post Barrel Punta Cormorant

Punta Cormorant

References

- ↑ "Galápagos Islands Guided Tour - Isla Floreana, Ecuador". Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ Philbrick, Nathaniel (2001). In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-100182-8.

- 1 2 Nickerson, Thomas. "Account of the Ship Essex Sinking, 1819-1821". Nantucket, Massachusetts: Nantucket Historical Society. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Keynes, R. D. ed. 2001. Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 356.

- ↑ Marcel E. Nordlohne, M. D. "Seven-Year Search for Nicholas Oliver Lawson". galapagos.to. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ↑ "In Depth in Galápagos Islands at Frommer's". Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ Minster, C. (2014). "Unsolved Murder Mystery: The Galápagos Affair". About.Com. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ↑ O'Malley, S. (2014-04-04). "Review of The Galapagos Affair-Satan Came to Eden". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ↑ Fitter, Julian; Fitter, Daniel; and Hosking, David. (2000) Wildlife of the Galápagos. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p.83.

- ↑ Fitter, Julian; Fitter, Daniel; and Hosking, David. (2000) Wildlife of the Galápagos. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p.68.

- 1 2 "Extinct Galápagos tortoise may just be hiding : Nature News Blog". Blogs.nature.com. 2013-07-11. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ↑ "'Extinct' giant Floreana tortoise may be alive, say scientists | Nature". The Earth Times. 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ↑ "Extinct Galápagos Tortoise Could Be Resurrected". News.nationalgeographic.com. 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

Bibliography

- Strauch, Dora (1936). Satan Came to Eden. Harper & brothers. OCLC 3803834.

- Treherne, John E. (1983). The Galápagos Affair. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4464-6788-6. OCLC 9731840.

- Wittmer, Margaret (2013). Floreana: A Woman's Pilgrimage to the Galápagos. Midpoint Trade Books Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-55921-399-8. OCLC 857863449.

- Egnal, George Frederick Ritter My Evil Paradise Floreana (Amazon Kindle Ebook, 2013)

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Floreana. |