Flatfish

| Flatfish Temporal range: Paleocene–Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

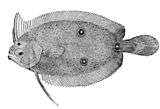

| A camouflaged flatfish. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Superorder: | Acanthopterygii |

| Order: | Pleuronectiformes |

| Families | |

|

Suborder Psettodoidei

Suborder Pleuronectoidei

Suborder Soleoidei

| |

A flatfish is a member of the order Pleuronectiformes of ray-finned demersal fishes, also called the Heterosomata, sometimes classified as a suborder of Perciformes. In many species, both eyes lie on one side of the head, one or the other migrating through and around the head during development. Some species face their left sides upward, some face their right sides upward, and others face either side upward.

Many important food fish are in this order, including the flounders, soles, turbot, plaice, and halibut. Some flatfish can actively camouflage themselves on the ocean floor.

Taxonomy

Over 700 species are in the 11 families. The largest families are Bothidae, Cynoglossidae, Paralichthyidae, Pleuronectidae, and Soleidae, with more than 100 species each (the remaining families have less than 50 species each). Some families are the results of relatively recent splits. For example, the Achiridae were classified as a subfamily of Soleidae in the past, and the Samaridae were considered a subfamily of the Pleuronectidae.[2][3] The Pleuronectidae may be split further still, as some authorities elevate Paralichthodinae, Poecilopsettinae, and Rhombosoleinae to families instead of subfamilies.[3]

The taxonomy of some groups is in need of a review, as the last monograph covering the entire order was John Roxborough Norman's Monograph of the Flatfishes published in 1934. New species are described with some regularity and undescribed species likely remain.[2]

Hybrids

Hybrids are well known in flatfishes. The Pleuronectidae, of marine fishes, have the largest number of reported hybrids.[4] Two of the most famous intergeneric hybrids are between the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and European flounder (Platichthys flesus) in the Baltic Sea,[5] and between the English sole (Parophrys vetulus) and starry flounder (Platichthys stellatus) in Puget Sound. The offspring of the latter species pair is popularly known as the hybrid sole and was initially believed to be a valid species in its own right.[4]

Distribution

Flatfishes are found in oceans worldwide, ranging from the Arctic, through the tropics, to Antarctica. Most species are found in depths between 0 and 500 m (1,600 ft), but a few have been recorded from depths in excess of 1,500 m (4,900 ft). None have been confirmed from the abyssal or hadal zones. An observation of a flatfish from the Bathyscaphe Trieste at the bottom of the Mariana Trench at a depth of almost 11 km (36,000 ft) has been questioned by fish experts, and recent authorities do not recognize it as valid.[6] Among the deepwater species, Symphurus thermophilus lives in congregating around "ponds" of sulphur at hydrothermal vents on the seafloor. No other flatfish is known from hydrothermal vents.[7] Many species will enter brackish or fresh water, and a smaller number of soles (families Achiridae and Soleidae) and tonguefish (Cynoglossidae) are entirely restricted to fresh water.[8][9][10]

Characteristics

The most obvious characteristic of the flatfish is its asymmetry, with both eyes lying on the same side of the head in the adult fish. In some families, the eyes are usually on the right side of the body (dextral or right-eyed flatfish), and in others, they are usually on the left (sinistral or left-eyed flatfish). The primitive spiny turbots include equal numbers of right- and left-sided individuals, and are generally less asymmetrical than the other families.[1] Other distinguishing features of the order are the presence of protrusible eyes, another adaptation to living on the seabed (benthos), and the extension of the dorsal fin onto the head.

The surface of the fish facing away from the sea floor is pigmented, often serving to camouflage the fish, but sometimes with striking coloured patterns. Some flatfishes are also able to change their pigmentation to match the background, in a manner similar to a chameleon. The side of the body without the eyes, facing the seabed, is usually colourless or very pale.[1]

In general, flatfishes rely on their camouflage for avoiding predators, but some have conspicuous eyespots (e.g., Microchirus ocellatus) and several small tropical species (at least Aseraggodes, Pardachirus and Zebrias) are poisonous.[2][11][12] Juveniles of Soleichthys maculosus mimic toxic flatworms of the genus Pseudobiceros in both colours and swimming mode.[13][14] Conversely, a few octopus species have been reported to mimic flatfishes in colours, shape and swimming mode.[15]

The flounders and spiny turbots eat smaller fish, and have well-developed teeth. They sometimes seek prey in the midwater, away from the bottom, and show fewer extreme adaptations than other families. The soles, by contrast, are almost exclusively bottom-dwellers, and feed on invertebrates. They show a more extreme asymmetry, and may lack teeth on one side of the jaw.[1]

Flatfishes range in size from Tarphops oligolepis, measuring about 4.5 cm (1.8 in) in length, and weighing 2 g (0.071 oz), to the Atlantic halibut, at 2.5 m (8.2 ft) and 316 kg (697 lb).[1]

| This article is one of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| |

| Large pelagic |

| billfish, bonito mackerel, salmon shark, tuna |

|

|

| Forage |

| anchovy, herring menhaden, sardine shad, sprat |

|

|

| Demersal |

| cod, eel, flatfish pollock, ray |

| Mixed |

| carp, tilapia |

Species and species groups

Reproduction

Flatfishes lay eggs that hatch into larvae resembling typical, symmetrical, fish. These are initially elongated, but quickly develop into a more rounded form. The larvae typically have protective spines on the head, over the gills, and in the pelvic and pectoral fins. They also possess a swim bladder, and do not dwell on the bottom, instead dispersing from their hatching grounds as plankton.[1]

The length of the planktonic stage varies between different types of flatfishes, but eventually they begin to metamorphose into the adult form. One of the eyes migrates across the top of the head and onto the other side of the body, leaving the fish blind on one side. The larva also loses its swim bladder and spines, and sinks to the bottom, laying its blind side on the underlying surface.

Evolution

In 2008, a 50-million-year-old fossil, Amphistium, was identified as an early relative of the flatfish and transitional fossil.[16] In a typical modern flatfish, the head is asymmetric, with both eyes on one side of the head. In Amphistium, the transition from the typical symmetric head of a vertebrate is incomplete, with one eye placed near the top of the head.[17] The researchers concluded, "the change happened gradually, in a way consistent with evolution via natural selection—not suddenly, as researchers once had little choice but to believe."[16]

Flatfishes have been cited as dramatic examples of evolutionary adaptation. Richard Dawkins, in The Blind Watchmaker, explains the flatfishes' evolutionary history thus:

…bony fish as a rule have a marked tendency to be flattened in a vertical direction…. It was natural, therefore, that when the ancestors of [flatfish] took to the sea bottom, they should have lain on one side…. But this raised the problem that one eye was always looking down into the sand and was effectively useless. In evolution this problem was solved by the lower eye ‘moving’ round to the upper side.[18]

The European plaice is the principal commercial flatfish in Europe.

The European plaice is the principal commercial flatfish in Europe. American soles are found in both freshwater and marine environments of the Americas.

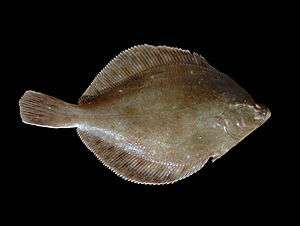

American soles are found in both freshwater and marine environments of the Americas. Halibut are the largest of the flatfishes, and provide lucrative fisheries.

Halibut are the largest of the flatfishes, and provide lucrative fisheries. The turbot is a large, left-eyed flatfish found in sandy shallow coastal waters around Europe.

The turbot is a large, left-eyed flatfish found in sandy shallow coastal waters around Europe. Flatfish (left‐eyed flounder)

Flatfish (left‐eyed flounder)

As food

Flatfish is considered a Whitefish[19] because of the high concentration of oils within its liver. Its lean flesh makes for a unique flavor that differs from species to species. Methods of cooking include grilling, pan-frying, baking and deep-frying.

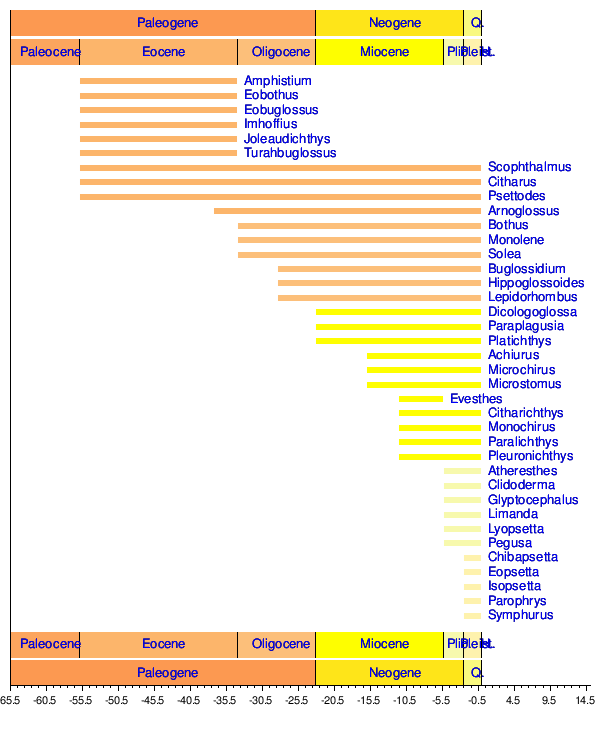

Timeline of genera

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pleuronectiformes. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chapleau, Francois; Amaoka, Kunio (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N., eds. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. xxx. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- 1 2 3 Randall, J. E. (2007). Reef and Shore Fishes of the Hawaiian Islands. ISBN 1-929054-03-3

- 1 2 Cooper, J.A.; and Chapleau, F. (1998). Monophyly and intrarelationships of the family Pleuronectidae (Pleuronectiformes), with a revised classification. Fish. Bull. 96 (4): 686–726.

- 1 2 Garrett, D.L.; Pietsch, T.W.; Utter, F.M.; and Hauser, L. (2007). The Hybrid Sole Inopsetta ischyra (Teleostei: Pleuronectiformes: Pleuronectidae): Hybrid or Biological Species? American Fisheries Society 136: 460–468

- ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Platichthys flesus (Linnaeus, 1758).. Retrieved 18 May 2014

- ↑ Jamieson, A.J., and Yancey, P. H. (2012). On the Validity of the Trieste Flatfish: Dispelling the Myth. The Biological Bulletin 222(3): 171-175

- ↑ Munroe, T.A.; and Hashimoto, J. (2008). A new Western Pacific Tonguefish (Pleuronectiformes: Cynoglossidae): The first Pleuronectiform discovered at active Hydrothermal Vents. Zootaxa 1839: 43–59.

- ↑ Duplain, R.R.; Chapleau, F; and Munroe, T.A. (2012). A New Species of Trinectes (Pleuronectiformes: Achiridae) from the Upper Río San Juan and Río Condoto, Colombia. Copeia 2012 (3): 541-546.

- ↑ Kottelat, M. (1998). Fishes of the Nam Theun and Xe Bangfai basins, Laos, with diagnoses of twenty-two new species (Teleostei: Cyprinidae, Balitoridae, Cobitidae, Coiidae and Odontobutidae). Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwat. 9(1):1-128.

- ↑ Monks, N. (2007). Freshwater flatfish, order Pleuronectiformes. Retrieved 18 May 2014

- ↑ Elst, R. van der (1997) A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of South Africa. ISBN 978-1868253944

- ↑ Debelius, H. (1997). Mediterranean and Atlantic Fish Guide. ISBN 978-3925919541

- ↑ Practical Fishkeeping (22 May 2012) Video: Tiny sole mimics a flatworm. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ Australian Museum (5 November 2010). This week in Fish: Flatworm mimic and shark teeth. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ Hanlon, R.T.; Warson, A.C.; and Barbosa, A. (2010). A “Mimic Octopus” in the Atlantic: Flatfish Mimicry and Camouflage by Macrotritopus defilippi. The Biological Bulletin 218(1): 15-24

- 1 2 "Odd Fish Find Contradicts Intelligent-Design Argument". National Geographic. July 9, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ Matt Friedman (2008). "The evolutionary origin of flatfish asymmetry" (PDF). Nature Letters. 454 (7201): 209–212. doi:10.1038/nature07108. PMID 18615083.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1991). The Blind Watchmaker. London: Penguin Books. p. 92. ISBN 0-14-014481-1.

- ↑ "Flatfish BBC".

Further references

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-17.

- Gibson, Robin N (Ed) (2008) Flatfishes: biology and exploitation. Wiley.

- Munroe, Thomas A (2005) "Distributions and biogeography." Flatfishes: Biology and Exploitation: 42-67.

.png)