Constitution of the Republic of China

|

Constitution of the Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國憲法 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国宪法 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

| Commonly known as Taiwan |

|

Leadership |

|

|

|

Other branches

|

|

Related topics |

|

Taiwan portal |

The Constitution of the Republic of China (Chinese: 中華民國憲法; pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínguó Xiànfǎ) is the fundamental law of the Republic of China (ROC), which since 1949 only controls the "free area of the Republic of China", which is essentially the island of Taiwan and some minor outlying islands, the only territories not lost to the Chinese Communists in the Chinese Civil War. It was adopted by the National Constituent Assembly on 25 December 1946, and went into effect on 25 December 1947, at a time when the ROC still had nominal control of Mainland China and to which this constitution applied. This made China (with approx. 450 million people at that time) the most populous "paper democracy" in the world. The latest revision to the constitution was in 2004.[1]

Drafted by the Kuomintang (KMT) as part of its third stage of national development (i.e., representative democracy), it established a centralized republic with five branches of government. Though the Constitution was intended for the whole China, it was neither extensively nor effectively implemented as the KMT was already fully embroiled in a civil war with the Communist Party of China by the time of its promulgation.

Following the KMT's retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion ("Temporary Provisions" for short) gave the KMT government extra-constitutional powers. Despite the Constitution, Taiwan was an authoritarian one-party state. Democratization began in the 1980s. Martial law was lifted in 1987, and in 1991 the Temporary Provisions were repealed and the Constitution amended to reflect the government's loss of mainland China, and the Constitution finally formed the basis of a multi-party democracy.

During the 1990s and early 2000s (decade), the Constitution's origins in mainland China led to supporters of "Taiwan independence" to push for a new Taiwanese constitution.[2][3][4] However, attempts by the Democratic Progressive Party administration to create a new Constitution during the second term of DPP President Chen Shui-bian failed, because the then opposition Kuomintang controlled the Legislative Yuan.[5][6] It was only agreed to reform the Constitution of the Republic of China, not to create a new one. It was lastly amended in 2005, with the consent of both the KMT and the DPP.

History

The Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China was drawn up in March 1912 and formed the basic government document of the Republic of China until 1928. It provided a Western-style parliamentary system headed by a weak president. However, the system was quickly usurped when Song Jiaoren, who as leader of the KMT was to become prime minister following the party's victory in the 1913 elections, was assassinated by the orders of President Yuan Shikai.[7] Yuan regularly flouted the elected assembly and assumed dictatorial powers. Upon his death in 1916, China disintegrated into warlordism and the Beiyang Government operating under the Constitution remained in the hands of various military leaders.

The Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek established control over much of China by 1928. The Nationalist Government promulgated the Provisional Constitution of the Political Tutelage Period on May 5, 1931, which was called the "Five Five Constitution." Under this document, the government operated under a one-party system with supreme power held by the National Congress of the Kuomintang and effective power held by the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang. In Leninist fashion, it permitted a system of dual party-state committees to form the basis of government. The KMT intended this Constitution to remain in effect until the country had been pacified and the people sufficiently "educated" to participate in democratic government.

The current Constitution traces its origins to the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The impending outbreak of the Chinese Civil War pressured Chiang Kai-shek into enacting a democratic Constitution that would end KMT one-party rule. The Communists sought a coalition of one-third Nationalists, one-third Communists, and one-third other parties, to form a government that would draft the new Constitution. However, while rejecting this idea, the KMT and the CCP jointly held a convention at which both parties presented views. Amidst heated debate, many of the demands from the Communist Party were met, including the popular election of the Legislative Yuan. Together, these drafts are called the Constitutional Draft of the Political Convention (政協憲草). The Constitution, with minor revisions from the latest draft, was adopted by the National Assembly on December 25, 1946, promulgated by the National Government on January 1, 1947, and went into effect on December 25, 1947. The Constitution was seen as the third and final stage of Kuomintang reconstruction of China. The Communists, though they attended the convention, and participated in drafting the constitution, boycotted the National Assembly and declared after the ratification that not only would they not recognize the ROC constitution, but all bills passed by the Nationalist administration would be disregarded as well. However, due to their showing in the election (approx. 800 out of 3045 seats,) their boycott did not prevent the Assembly from reaching quorum and thus electing Chiang Kai-shek and Lee Tsung-ren (李宗仁) as President and Vice President respectively. Zhou Enlai challenged the legitimacy of the National Assembly in 1947 by asserting that the KMT hand-picked its members 10 years earlier, and thus the Assembly could not be the legal representatives of the Chinese people.

Content

The founding of the ROC was centered on the Three Principles of the People (Sān Mín Zhǔyì), which called for the establishment of a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. A government for the people invoked the idea of civic nationalism, which sought to create unity between the five traditional ethnic groups in China (Han, Manchus, Mongols, Hui (Muslims), and Tibetans) in order to stand up to European and Japanese imperialism as one, strong nation. A government by the people sought to create a Western parliamentary democracy and a separation of powers. Originally, the National Assembly was the "parliament" of the republic, but it lost relevance in the 1990s and was abolished in 2005 with its powers transferred to the Legislative Yuan. Dr. Sun also added two branches of government from the legacy of China's imperial past to the three branches of Western governments. The five branches or Yuan (院) are: the Executive Yuan, Legislative Yuan, Judicial Yuan, Examination Yuan, and Control Yuan. While the original intent was to have a parliamentary system (as evidenced in the existence of both a president and premier), due to the Temporary Provisions, Gimo Chiang Kai-shek was allowed by the National Assembly to reduce the function of the premier and to concentrate more power in the presidency. As a result, the current government is in practice a semi-presidential system. A government for the people means that the government to a certain extent must provide services that are essential to the well-being of society. Examples of this principle in practice are the New Life Movement and National Health Insurance.

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People are Minzu, Minquan, and Minsheng, roughly defined as nationalism, democracy, and the livelihood of the people.[8]

Application in Taiwan

Suspension of the constitution and martial law

On January 10, 1947, Governor Chen Yi announced that the new ROC Constitution would not apply to Taiwan after it went into effect in mainland China on December 25, 1947 as Taiwan was still under military occupation and also that Taiwanese were politically naive and were not capable of self-governing.[9] Later that year, Chen Yi was dismissed and the Taiwan Provincial Government was established. From March 1947 until 1987, Taiwan was in a state of martial law. Although the constitution provided for regular democratic elections, these were not held in Taiwan until the 1990s.

On April 18, 1948, the National Assembly added to the Constitution the "Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion". These articles greatly enhanced the power of the president and abolished the two term limit for the president and the vice president. In 1954, the Judicial Yuan ruled that the delegates elected to the National Assembly and Legislative Yuan in 1947 would remain in office until new elections could be held in Mainland China which had come under the control of the Communist Party of China in 1949. This judicial ruling allowed the Kuomintang to rule unchallenged in Taiwan until the 1990s. In 1991, these members were ordered to resign by a subsequent Judicial Yuan ruling.

In the 1970s, supplemental elections began to be held for the Legislative Yuan. Although these were for a limited number of seats, they did allow for the transition to a more open political system.

Democratization

In the late 1980s, the Constitution faced the growing democratization on Taiwan combined with the mortality of the delegates that were elected in 1947. Faced with these pressures, on April 22, 1991, the first National Assembly voted itself out of office, abolished the Temporary Provisions passed in 1948, and adopted major amendments (known as the "First Revision") permitting free elections.

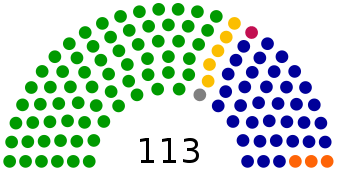

On May 27, 1992 several other amendments were passed (known as the "Second Revision"), most notably that allowing the direct election of the President of the Republic of China, Governor of Taiwan Province, and municipal mayors. Ten new amendments to replace the eighteen amendments of the First and Second Revisions were passed on July 28, 1994. The amendments passed on July 18, 1997 streamlined the Taiwan Provincial Government and granted the Legislative Yuan powers of impeachment. The constitution was subsequently revised in 1999 and 2000, with the former revision being declared void the same year by the Council of Grand Justices. A further revision of the constitution happened in 2005 which disbanded the National Assembly, reformed the Legislative Yuan, and provided for future constitutional change to be ratified by referendum.

Passing an amendment to the ROC constitution now requires an unusually broad political consensus, which includes approval from three-fourths of the quorum of members of the Legislative Yuan. This quorum requires at least three-fourths of all members of the Legislature. After passing the Legislature, the amendments need ratification by at least fifty percent of all eligible voters of the ROC irrespective of voter turnout.

It should also be noted that, because the ROC constitution is, at least nominally, the constitution of all China, the amendments avoided any specific reference to the Taiwan area and instead used the geographically neutral term "Free Area of the Republic of China" to refer to all areas under ROC control. In addition, as the preamble of the amendments stated they are [t]o meet the requisites of the nation prior to national unification, these amendments would automatically be voided in the case of Chinese reunification. As a result, all post-1991 amendments have been maintained as a separate part of the Constitution, consolidated into a single text of twelve articles.

Challenge of legitimacy

A number of criticisms have been leveled at the ROC constitution by supporters of Taiwan independence. Until the 1990s, the document was considered illegitimate by pro-independence advocates because it was not drafted in Taiwan; moreover, they deemed Taiwan to be sovereign Japanese territory until ceded in the San Francisco Peace Treaty effective April 28, 1952. Pro-independence advocates have argued that the Constitution was never legally applied to Taiwan because Taiwan was not formally incorporated into the ROC's territory through the National Assembly as per the specifications of Article 4. Though the constitution promulgated in 1946 did not define the territory of the Republic of China, while the draft of the constitution of 1925 individually listed the provinces of the Republic of China and Taiwan was not among them, since Taiwan was part of Japan as the result of the Treaty of Shimonoseki of 1895. The constitution also stipulated in the Article I.4, that "the territory of the ROC is the original territory governed by it, unless authorized by the National Assembly, can not be altered." In 1946, Sun Fo, the minister of the Executive Yuan of ROC reported to the National Assembly that "there are two types of territory changes: 1. renouncing territory and 2. annexing new territory. The first example would be the Independence of Mongolia, and the second example would be the reclamation of Taiwan. Both would be examples of territory changes. No such formal annexation of Taiwan islands by the ROC National Assembly conforming with the ROC constitution ever occurred since 1946, even though Article 9 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China says, "The modifications of the functions, operations, and organization of the Taiwan Provincial Government may be specified by law." The Republic of China argues that sovereignty of the Republic of China over Taiwan was established by the Instrument of Surrender of Japan which implemented the Potsdam Declaration and the Cairo Declaration. The Allies have not agreed or disagreed to this rationale. In addition, the ROC argues that the Article 4 of Treaty of Taipei nullifies the Treaty of Shimonoseki and the original transfer of sovereignty of Taiwan from China to Japan. Since this transfer of sovereignty occurred in 1945 before the promulgation of the 1947 constitution, the ROC government is of the view that a resolution by the National Assembly was unnecessary.

While both symbolic and legal arguments have been used to discredit the application the ROC Constitution in Taiwan, the document gained more legitimacy among independence supporters throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s due to democratization and it is now accepted as the basic law of the Republic of China by all of the major parties. However, there are proposals being floated, particularly by supporters of Taiwan independence and the supporters of Taiwan localization movement, to replace the current Constitution with a document drafted by the Taiwanese constituencies in Taiwan.

The basic four rights of people

Chapter 12 enshrines the so-called four rights of the people: election of public officials, recall of public officials, legislative initiative, and referendum.

Referendums and constitutional reform

One recent controversy involving the constitution is the right to referendum which is mentioned in the Constitution. The constitution states that "The exercise of the rights of initiative and referendum shall be prescribed by law",[10] but legislation prescribing the practices had been blocked by the pan-blue coalition largely out of suspicions that proponents of a referendum law would be used to overturn the ROC Constitution and provide a means to declare Taiwan independence. A referendum law was passed on 27 November 2003[11] and signed by President Chen Shui-bian on 31 December 2003,[12] but the law sets high standards for referendums such as the requirement that they can only be called by the President in times of imminent attack.[12]

In 2003, President Chen Shui-bian proposed holding a referendum in 2006 for implementing an entirely new constitution on May 20, 2008 to coincide with the inauguration of the 12th-term president of the ROC. Proponents of such a move, namely the Pan-Green Coalition, argue that the current Constitution endorses a specific ideology (i.e., the Three Principles of the People), which is only appropriate for Communist states; in addition, they argue that a more "efficient" government is needed to cope with changing realities. Some proponents support replacing the five-branch structure outlined by the Three Principles of the People with a three-branch government. Others cite the current deadlock between the executive and legislative branches and support replacing the presidential system with a parliamentary system. Furthermore, the current Constitution explicitly states before the amendments implemented on Taiwan, "To meet the requisites of the nation prior to national unification...", in direct opposition to the pan-green position that Taiwan must remain separated from the mainland. In response, the pan-blue coalition dropped its opposition to non-constitutional referendums and offered to consider through going constitutional reforms.

The proposal to implement an entirely new constitution met with strong opposition from the People's Republic of China and great unease from the United States, both of which feared the proposal to rewrite the constitution to be a veiled effort to achieve Taiwan independence, as it would sever a legal link to mainland China, and to circumvent Chen's original Four Noes and One Without pledge. In December 2003, the United States announced its opposition to any referendum that would tend to move Taiwan toward formal "independence", a statement that was widely seen as being directed at Chen's constitutional proposals.

In response, the Pan-Blue Coalition attempted to argue that a new constitution and constitutional referendums were unnecessary and that the inefficiencies in the ROC Constitution could be approved through the normal legislative process.

In his May 20, 2004 inaugural address, Chen called for a "Constitutional Reform Committee" to be formed by "members of the ruling party and the opposition parties, as well as legal experts, academic scholars and representatives from all fields and spanning all social classes" to decide on the proper reforms. He promised that the new Constitution would not change the issue of sovereignty and territory. This proposal went nowhere due to lack of cooperation from the opposition Pan-Blue.

Former President Ma Ying-jeou stated that constitutional reform was not a priority for his government.[13]

See also

- Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China

- Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China

- History of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Kuomintang

References

- ↑ "Introduction(3)". Office of the President, Republic of China (Taiwan). Seventh revision. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ↑ Chang, Yun-ping (2004-07-02). "Lee launches constitution campaign". Taipei Times.

- ↑ Ko, Shu-ling (2007-03-19). "Group pushes new constitution". Taipei Times.

- ↑ Wu, Ming-chi (2003-10-28). "US, EU apt constitutional models". Taipei Times.

- ↑ Wu, Sofia (2004-04-22). "New Constitution plan not independence timetable: Presidential Office". Global Security. CNA.

- ↑ Chang, Yun-ping (2003-11-21). "DPP, KMT agree to debate between Chen and Lien". Taipei Times.

- ↑ Xiang, Ah. "Song Jiaoren's Assassination & Second Revolution" (PDF). Republican China. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- ↑ Dirlik, Arif (2005). Marxism in the Chinese revolution. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 26. ISBN 9780742530690.

- ↑ Kerr, George H. (1965) Formosa Betrayed, Boston Houghton Mifflin: p240

- ↑

Constitution of the Republic of China. Wikisource. Chapter XII: ELECTION, RECALL, INITIATIVE AND REFERENDUM, Article 136.

Constitution of the Republic of China. Wikisource. Chapter XII: ELECTION, RECALL, INITIATIVE AND REFERENDUM, Article 136. - ↑ "Taiwan passes watered-down referendum bill". People's Daily. 2003-11-28. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- 1 2 "Taiwan referendum law signed". BBC News. 2003-12-31. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ↑ Mo, Yan-chih (2006-05-01). "Ma says constitutional reform not the answer". Taipei Times. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Main Text of the Constitution of the Republic of China (Taiwan)". Office of the President, Republic of China (Taiwan). Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- Hsueh, Hua-yuen (2001-12-24). "Constitution Day and Constitutional Government" 行憲紀念日與憲政. 吳三連台灣史料基金會首頁 (in Chinese and English).