First Sumatran expedition

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The First Sumatran expedition, which featured the Battle of Quallah Battoo (Aceh: Kuala Batèë, Malay: Kuala Batu) in 1832, was a punitive expedition by the United States Navy against the village of Kuala Batee, presently a subdistrict in Southwest Aceh Regency. The reprisal was in response to the massacre of the crew of the merchantman Friendship a year earlier. The frigate Potomac and its crew defeated the local uleëbalang (ruler)'s forces and bombed the settlement. The expedition was successful in stopping Sumatran attacks on U.S. shipping for six years until another vessel was plundered under different circumstances, resulting in a second Sumatran expedition in 1838.

Background

The island of Sumatra is renowned as an excellent source of pepper, and throughout history ships have come to the island to trade for it. In 1831, the American merchantman Friendship under Captain Charles Endicott had arrived off the chiefdom of Kuala Batu in order to secure a cargo of pepper. Various small trading boats darted back and forth along the coast trading pepper with the merchant ships waiting offshore. On 7 February 1831, Endicott and a few of his men went ashore to purchase some pepper from the natives when three proas attacked his ship, murdered Friendship's first officer and two other of her crew, and plundered its cargo.[1]

Endicott and the other surviving members of his crew managed to escape to another port with the assistance of a friendly native chief named Po Adam. There they enlisted the help of three other merchant captains who agreed to help him recover his vessel. With their help, Endicott managed to retake his ship and eventually sailed back to Salem, Massachusetts. Upon reaching Salem there was a general public outcry against the massacre and in response President Andrew Jackson dispatched the frigate USS Potomac under Commodore John Downes to punish the natives for their treachery.[2]

The Dutch expedition on the west coast of Sumatra of 1831 by the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army was in response to the incident, and served as an excuse to annex parts of the Aceh Sultanate.

Battle

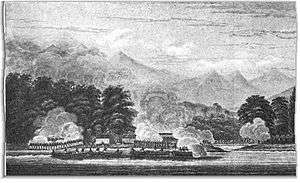

Potomac reached Kuala Batu on 5 February 1832. Here Downes met Po Adam who advised him that the local uleëbalang would in no way be partial toward paying compensation for the attack on Friendship. Commodore Downes then decided to disguise his ship as a Danish merchantman in order to keep the element of surprise in his favor. The disguise worked so well that when a party of Malays boarded Potomac attempting to sell a cargo of pepper they were, much to their surprise, detained so as not to alert Kuala Batu of the real identity of Potomac. Downes then sent a reconnaissance party to scout out the defenses of the port, but this was repulsed by the Malays.[3][4] In addition to the three proas in the harbor, at least five forts were found to be guarding the town with the majority of them near the coastline.[5]

Downes ordered a detachment of 282 marines and bluejackets into the ship's boats, some of which had been equipped with a few of Potomac's lighter cannon. It was from these boats that the sailors and marines of Potomac burnt the Malay vessels in Kuala Batu's harbor and assaulted the town's forts while support from the guns of Potomac herself were used to suppress the fire coming from the Malay forts. The later-day muskets the Americans used were far superior to the outdated matchlock weapons of the Malays, but the natives fought fiercely and the fighting devolved into hand-to-hand combat in which one of the uleëbalang commanding the forts was killed along with about 150 other warriors.[6] Only two Americans died during the attack and another eleven sailors and marines suffering injuries.[7]

After the coastal forts fell, the remaining Malays fled toward the rear of the town where another fort lay, but instead of engaging the last remaining fort the Americans attacked the town itself. Large scale looting and pillaging occurred with a range of plunder being looted from the town as well as many civilians slain. Downes later ordered his men to return to the ship and bombarded the fifth fort as well as the town until its surviving leaders agreed to surrender, killing another 300 natives in the process.[8]

Aftermath

The remaining uleëbalang begged for mercy and Downes informed them that if any American ships were attacked again the same treatment would be given to the perpetrators. Other uleëbalang from nearby states also sent delegations to the ship pleading that Downes spare them from the same fate as Kuala Batu. Downes left the area to continue his journey eventually circumnavigating the globe, stopping at Hawaii and entertaining that nation's king and queen aboard his vessel.

Although some criticism arose from the fact that Downes did not attempt to negotiate a settlement by peaceable means, the general public was satisfied with his response and no action was taken against him.[9] The troubles with Kuala Batu were not over though; in 1838 another ship was attacked and its crew massacred. True to Downes' word the Second Sumatran expedition under George C. Read bombarded Kuala Batu and attacked the village of Muckie.[10]

See also

Citations

- ↑ Meacham, 213

- ↑ Warriner, 104

- ↑ Corn, 294

- ↑ The Leatherneck. Leatherneck Association. 1960. p. 51.

- ↑ Corn, 295

- ↑ Warriner, 94

- ↑ "Casualties: U. S. Navy and Marine Corps". history.navy.mil. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "The United States attack on Kuala Batu". sabrizain.org. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ Johnson, 44

- ↑ "Use of U.S. Forces Abroad". history.navy.mil. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

References

- Corn, Charles (1999). The scents of Eden: a history of the spice trade. New York: Kodansha America. ISBN 1-56836-249-8.

- Johnson, Robert Erwin (1980). Thence round Cape Horn. New York: Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-405-13040-6.

- Meacham, Jon (2008). American lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. New York: Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6325-6.

- Warriner, Francis (1835). Cruise of the United States frigate Potomac round the world: during the years 1831-34. New York: Leavitt, Lord & Co.

External links

Coordinates: 3°45′27″N 96°45′51″E / 3.757375°N 96.76403°E