First Barbary War

| First Barbary War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Barbary Wars | |||||||

USS Enterprise fighting the Tripolitan polacca Tripoli by William Bainbridge Hoff, 1878 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

United States First Squadron: 4 frigates 1 schooner Second Squadron: 6 frigates 1 schooner Third Squadron: 2 frigates 3 brigs 2 schooners 1 ketch Swedish Royal Navy: 3 frigates William Eaton's invasion: 8 US Marines, William Eaton, 3 Midshipmen, and several civilians Approx. 500 Greek and Arab mercenaries |

Various cruisers 11–20 gunboats 4,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

United States: 35 killed 64 wounded Greek & Arab mercenaries: killed and wounded unknown | Estimated 800 dead, 1,200 wounded at Derne plus ships and crew lost in naval defeats | ||||||

The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitanian War and the Barbary Coast War, was the first of two Barbary Wars between the United States, Sweden and the four North African states known collectively as the "Barbary States". Three of these were nominal provinces of the Ottoman Empire, but in practice autonomous: Tripoli, Algiers, and Tunis. The fourth was the independent Sultanate of Morocco.[3] The cause of the war was pirates from the Barbary States seizing American merchant ships and holding the crews for ransom, demanding the U.S. pay tribute to the Barbary rulers. United States President Thomas Jefferson refused to pay this tribute, in addition the Swedes having been at war with the Tripolitans since 1800.[4]

Background and overview

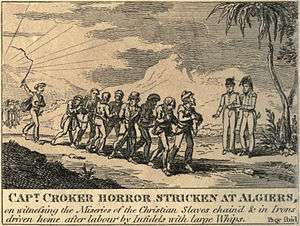

Barbary corsairs and crews from the North African Ottoman provinces of Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and the independent Sultanate of Morocco under the Alaouite dynasty (the Barbary Coast) were the scourge of the Mediterranean.[5] Capturing merchant ships and enslaving or ransoming their crews provided the Muslim rulers of these nations with wealth and naval power. The Roman Catholic Trinitarian Order, or order of "Mathurins", had operated from France for centuries with the special mission of collecting and disbursing funds for the relief and ransom of prisoners of Mediterranean pirates. According to Robert Davis, between 1 and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves between the 16th and 19th centuries.[6]

Barbary corsairs led attacks upon American merchant shipping in an attempt to extort ransom for the lives of captured sailors, and ultimately tribute from the United States to avoid further attacks, as they did with the various European states.[7] Before the Treaty of Paris, which formalized the United States' independence from Great Britain, U.S. shipping was protected by France during the revolutionary years under the Treaty of Alliance (1778–83). Although the treaty does not mention the Barbary States in name, it refers to common enemies between both the U.S. and France. As such, piracy against U.S. shipping only began to occur after the end of the American Revolution, when the U.S. government lost its protection under the Treaty of Alliance.

This lapse of protection by a European power led to the first American merchant ship being seized after the Treaty of Paris. On 11 October 1784, Moroccan pirates seized the brigantine Betsey.[8] The Spanish government negotiated the freedom of the captured ship and crew; however, Spain offered advice to the United States on how to deal with the Barbary States. The advice was to offer tribute to prevent further attacks against merchant ships. The U.S. Minister to France, Thomas Jefferson, decided to send envoys to Morocco and Algeria to try to purchase treaties and the freedom of the captured sailors held by Algeria.[9] Morocco was the first Barbary Coast State to sign a treaty with the U.S., on 23 June 1786. This treaty formally ended all Moroccan piracy against American shipping interests. Specifically, article six of the treaty states that if any Americans captured by Moroccans or other Barbary Coast States docked at a Moroccan city, they would be set free and come under the protection of the Moroccan State.[10]

American diplomatic action with Algeria, the other major Barbary Coast State, was much less productive than with Morocco. Algeria began piracy against the U.S. on 25 July 1785 with the capture of the schooner Maria, and Dauphin a week later.[11] All four Barbary Coast states demanded $660,000 each. However, the envoys were given only an allocated budget of $40,000 to achieve peace.[12] Diplomatic talks to reach a reasonable sum for tribute or for the ransom of the captured sailors struggled to make any headway. The crews of Maria and Dauphin remained in captivity for over a decade, and soon were joined by crews of other ships captured by the Barbary States.[13]

In 1795, Algeria came to an agreement that resulted in the release of 115 American sailors they held, at a cost of over $1 million. This amount totaled about one-sixth of the entire U.S. budget,[14] and was demanded as tribute by the Barbary States to prevent further piracy. The continuing demand for tribute ultimately led to the formation of the United States Department of the Navy, founded in 1798[15] to prevent further attacks upon American shipping and to end the demands for extremely large tributes from the Barbary States.

Various letters and testimonies by captured sailors describe their captivity as a form of slavery, even though Barbary Coast imprisonment was different from that practiced by the U.S. and European powers of the time.[16] Barbary Coast prisoners were able to obtain wealth and property, along with achieving status beyond that of a slave. One such example was James Leander Cathcart, who rose to the highest position a Christian slave could achieve in Algeria, becoming an adviser to the bey (governor).[17] Even so, most captives were pressed into hard labor in the service of the Barbary pirates, and struggled under extremely poor conditions that exposed them to vermin and disease. As word of their treatment reached the U.S., through freed captives' narratives and letters, Americans pushed for direct government action to stop the piracy against U.S. ships.

In March 1786, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams went to London to negotiate with Tripoli's envoy, ambassador Sidi Haji Abdrahaman (or Sidi Haji Abdul Rahman Adja). When they enquired "concerning the ground of the pretensions to make war upon nations who had done them no injury", the ambassador replied:

"It was written in their Koran, that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful to plunder and enslave; and that every mussulman who was slain in this warfare was sure to go to paradise. He said, also, that the man who was the first to board a vessel had one slave over and above his share, and that when they sprang to the deck of an enemy's ship, every sailor held a dagger in each hand and a third in his mouth; which usually struck such terror into the foe that they cried out for quarter at once." [18]

Jefferson reported the conversation to Secretary of Foreign Affairs John Jay, who submitted the ambassador's comments and offer to Congress. Jefferson argued that paying tribute would encourage more attacks. Although John Adams agreed with Jefferson, he believed that circumstances forced the U.S. to pay tribute until an adequate navy could be built. The U.S. had just fought an exhausting war, which put the nation deep in debt. Federalist and Anti-Federalist forces argued over the needs of the country and the burden of taxation. Jefferson's own Democratic-Republicans and anti-navalists believed that the future of the country lay in westward expansion, with Atlantic trade threatening to siphon money and energy away from the new nation, to be spent on wars in the Old World.[25] The U.S. paid Algiers the ransom, and continued to pay up to $1 million per year over the next 15 years for the safe passage of American ships and the return of American hostages. A $1 million payment in ransom and tribute to the privateering states amounted to approximately 10% of the U.S. government's annual revenues in 1800.[26]

Jefferson continued to argue for cessation of the tribute, with rising support from George Washington and others. With the recommissioning of the American Navy in 1794 and the resulting increased firepower on the seas, it became increasingly possible for America to refuse paying tribute, although by now the long-standing habit was hard to overturn.

Declaration of war and naval blockade

Just before Jefferson's inauguration in 1801, Congress passed naval legislation that, among other things, provided for six frigates that 'shall be officered and manned as the President of the United States may direct.' ... In the event of a declaration of war on the United States by the Barbary powers, these ships were to 'protect our commerce and chastise their insolence—by sinking, burning or destroying their ships and vessels wherever you shall find them.'"[27] On Jefferson's inauguration as president in 1801, Yusuf Karamanli, the Pasha (or Bashaw) of Tripoli, demanded $225,000 (equivalent to $3.21 million in 2015) from the new administration. (In 1800, federal revenues totaled a little over $10 million). Putting his long-held beliefs into practice, Jefferson refused the demand. Consequently, on 10 May 1801, the Pasha declared war on the U.S., not through any formal written documents but in the customary Barbary manner of cutting down the flagstaff in front of the U.S. Consulate.[28] Algiers and Tunis did not follow their ally in Tripoli.

Before learning that Tripoli had declared war on the United States, Jefferson sent a small squadron, consisting of three frigates and one schooner, under the command of Commodore Richard Dale with gifts and letters to attempt to maintain peace with the Barbary powers.[29] However, in the event that war had been declared, Dale was instructed "to protect American ships and citizens against potential aggression," but Jefferson "insisted that he was 'unauthorized by the constitution, without the sanction of Congress, to go beyond the line of defense.'" He told Congress: "I communicate [to you] all material information on this subject, that in the exercise of this important function confided by the constitution to the legislature exclusively their judgment may form itself on a knowledge and consideration of every circumstance of weight."[27] Although Congress never voted on a formal declaration of war, they did authorize the President to instruct the commanders of armed American vessels to seize all vessels and goods of the Pasha of Tripoli "and also to cause to be done all such other acts of precaution or hostility as the state of war will justify." The American squadron joined a Swedish flotilla under Rudolf Cederström in blockading Tripoli, the Swedes having been at war with the Tripolitans since 1800.[4]

On 31 May 1801, Commodore Edward Preble traveled to Messina, Sicily, to the court of King Ferdinand IV of the Kingdom of Naples. The kingdom was at war with Napoleon, but Ferdinand supplied the Americans with manpower, craftsmen, supplies, gunboats, mortar boats, and the ports of Messina, Syracuse and Palermo to be used as a naval base to launch operations against Tripoli, a port walled fortress city protected by 150 pieces of heavy artillery manned by 25,000 soldiers, assisted by a fleet of 10 ten-gunned brigs, 2 eight-gun schooners, two large galleys, and 19 gunboats.[30]

The schooner Enterprise (commanded by Lieutenant Andrew Sterret) defeated the 14-gun Tripolitan corsair Tripoli after a one-sided battle on 1 August 1801.

In 1802, in response to Jefferson's request for authority to deal with the pirates, Congress passed "An act for the protection of commerce and seamen of the United States against the Tripolitan cruisers", authorizing the President to "…employ such of the armed vessels of the United States as may be judged requisite… for protecting effectually the commerce and seamen thereof on the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean and adjoining seas."[31] "The statute authorized American ships to seize vessels belonging to the Bey of Tripoli, with the captured property distributed to those who brought the vessels into port."[27]

The U.S Navy went unchallenged on the sea, but still the question remained undecided. Jefferson pressed the issue the following year, with an increase in military force and deployment of many of the navy's best ships to the region throughout 1802. Argus, Chesapeake, Constellation, Constitution, Enterprise, Intrepid, Philadelphia and Syren all saw service during the war under the overall command of Preble. Throughout 1803, Preble set up and maintained a blockade of the Barbary ports and executed a campaign of raids and attacks against the cities' fleets.

Battles

In October 1803, Tripoli's fleet captured USS Philadelphia intact after the frigate ran aground on a reef while patrolling Tripoli harbor. Efforts by the Americans to float the ship while under fire from shore batteries and Tripolitan Naval units failed. The ship, its captain, William Bainbridge, and all officers and crew were taken ashore and held as hostages. Philadelphia was turned against the Americans and anchored in the harbor as a gun battery.

—Horatio Nelson

On the night of 16 February 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur led a small detachment of U.S. Marines aboard the captured Tripolitan ketch rechristened USS Intrepid, thus deceiving the guards on Philadelphia to float close enough to board her. Decatur's men stormed the ship and overpowered the Tripolitan sailors. With fire support from the American warships, the Marines set fire to Philadelphia, denying her use by the enemy. British admiral, Horatio Nelson, himself known as a man of action and courage, reportedly called this "the most bold and daring act of the age."[32]

Preble attacked Tripoli on 14 July 1804, in a series of inconclusive battles, including a courageous but unsuccessful attack attempting to use Intrepid under Captain Richard Somers as a fire ship, packed with explosives and sent to enter Tripoli harbor, where she would destroy herself and the enemy fleet. However, Intrepid was destroyed, possibly by enemy gunfire, before she achieved her goal, killing Somers and his entire crew.[33]

The turning point in the war was the Battle of Derna (April–May 1805). Ex-consul William Eaton, a former Army captain who used the title of "general", and US Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Presley O'Bannon led a force of eight U.S. Marines [34] and five hundred mercenaries—Greeks from Crete, Arabs, and Berbers on a march across the desert from Alexandria, Egypt, to capture the Tripolitan city of Derna. This was the first time the United States flag was raised in victory on foreign soil. The action is memorialized in a line of the Marines' Hymn—"the shores of Tripoli".[35] The capturing of the city gave American negotiators leverage in securing the return of hostages and the end of the war.[36]

Peace treaty and legacy

Wearied of the blockade and raids, and now under threat of a continued advance on Tripoli proper and a scheme to restore his deposed older brother Hamet Karamanli as ruler, Yusuf Karamanli signed a treaty ending hostilities on 10 June 1805. Article 2 of the treaty reads:

The Bashaw of Tripoli shall deliver up to the American squadron now off Tripoli, all the Americans in his possession; and all the subjects of the Bashaw of Tripoli now in the power of the United States of America shall be delivered up to him; and as the number of Americans in possession of the Bashaw of Tripoli amounts to three hundred persons, more or less; and the number of Tripolino subjects in the power of the Americans to about, one hundred more or less; The Bashaw of Tripoli shall receive from the United States of America, the sum of sixty thousand dollars, as a payment for the difference between the prisoners herein mentioned.[37]

In agreeing to pay a ransom of $60,000 for the American prisoners, the Jefferson administration drew a distinction between paying tribute and paying ransom. At the time, some argued that buying sailors out of slavery was a fair exchange to end the war. William Eaton, however, remained bitter for the rest of his life about the treaty, feeling that his efforts had been squandered by the state department diplomat Tobias Lear. Eaton and others felt that the capture of Derna should have been used as a bargaining chip to obtain the release of all American prisoners without having to pay ransom. Furthermore, Eaton believed the honor of the United States had been compromised when it abandoned Hamet Karamanli after promising to restore him as leader of Tripoli. Eaton's complaints generally went unheard, especially as attention turned to the strained international relations which would ultimately lead to the withdrawal of the U.S. Navy from the area in 1807 and to the War of 1812.[38]

The First Barbary War was beneficial to the reputation of the United States' military command and war mechanism, which had been up to that time relatively untested. The First Barbary War showed that America could execute a war far from home, and that American forces had the cohesion to fight together as Americans rather than separately as Georgians or New Yorkers. The United States Navy and Marines became a permanent part of the American government and American history, and Decatur returned to the U.S. as its first post-revolutionary war hero.[39]

However, the more immediate problem of Barbary piracy was not fully settled. By 1807, Algiers had gone back to taking American ships and seamen hostage. Distracted by the preludes to the War of 1812, the U.S. was unable to respond to the provocation until 1815, with the Second Barbary War, in which naval victories by Commodores William Bainbridge and Stephen Decatur led to treaties ending all tribute payments by the U.S.[40]

Monument

The Tripoli Monument,[41] the oldest military monument in the U.S., honors the American heroes of the First Barbary War: Master Commandant Richard Somers, Lieutenant James Caldwell, James Decatur (brother of Stephen Decatur), Henry Wadsworth, Joseph Israel and John Dorsey. Originally known as the Naval Monument, it was carved of Carrara marble in Italy in 1806 and brought to the U.S. on board Constitution ("Old Ironsides"). From its original location in the Washington Navy Yard, it was moved to the west terrace of the national Capitol and finally, in 1860, to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.[42]

See also

- Arab slave trade

- Barbary slave trade

- Barbary treaties

- Islamic views on slavery

- Military history of the United States

- Second Barbary War

- Slavery in the Ottoman Empire

- To the Shores of Tripoli

References

- ↑ Mike Bacarella. "Barbary Wars". daddezio.com.

- ↑ Joseph Wheelan (21 September 2004). Jefferson's War: America's First War on Terror 1801–1805. PublicAffairs. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-0-7867-4020-8.

- ↑ Wars of the Barbary Pirates. pp. 16, 39. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- 1 2 Woods, Tom. "Presidential War Powers: The Constitutional Answer". Libertyclassroom.com. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ↑ Masselman, George. The Cradle of Colonialism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963. OCLC 242863. p. 205. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Davis, Robert. Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800.

- ↑ Rojas, Martha Elena. "'Insults Unpunished' Barbary Captives, American Slaves, and the Negotiation of Liberty." Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1.2 (2003): 159–86.

- ↑ Battistini, Robert. "Glimpses of the Other before Orientalism: The Muslim World in Early American Periodicals, 1785–1800." Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 8.2 (2010): 446–74.

- ↑ Parton, James. "Jefferson, American Minister in France." Atlantic Monthly. 30.180 (1872): 405–24.

- ↑ Miller, Hunter. United States. "Barbary Treaties 1786–1816: Treaty with Morocco June 28 and July 15, 1786". The Avalon Project, Yale Law School.

- ↑ Battistini, 450

- ↑ Parton, 413

- ↑ Rojas, 176

- ↑ Rojas, 165.

- ↑ Blum, Hester. "Pirated Tars, Piratical Texts Barbary Captivity and American Sea Narratives." Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1.2 (2003): 133–58.

- ↑ Rojas, 168–9.

- ↑ Rojas, 163

- ↑ "American Peace Commissioners to John Jay," March 28, 1786, "Thomas Jefferson Papers," Series 1. General Correspondence. 1651–1827, Library of Congress. LoC: March 28, 1786 (handwritten).

^ Philip Gengembre Hubert (1872). Making of America Project. The Atlantic Monthly, Atlantic Monthly Co. p. 413. (some sources confirm this wording,[19][20] other sources report this quotation with slight differences in wording.[21][22][23][24]) - ↑ Richard Lee (2011). In God We Still Trust: A 365-Day Devotional. Thomas Nelson Inc. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-4041-8965-2.

- ↑ Harry Gratwick (19 April 2010). Hidden History of Maine. The History Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-59629-815-6.

- ↑ United States. Dept. of State (1837). The diplomatic correspondence of the United States of America. Printed by Blair & Rives. p. 605.

- ↑ Priscilla H. Roberts; Richard S. Roberts (2008). Thomas Barclay (1728–1793): Consul in France, Diplomat in Barbary. Associated University Presse. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-934223-98-0.

- ↑ Frederick C. Leiner (2006). The End of Barbary Terror: America's 1815 War Against the Pirates of North Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-19-518994-0.

- ↑ United States Congressional Serial Set, Serial No. 15038, House Documents Nos. 129–137. Government Printing Office. p. 8. GGKEY:TBY2W8Z0L9N.

- ↑ London 2005, pp. 40,41.

- ↑ United States Federal State and Local Government Revenue, Fiscal Year 1800, in $ million, usgovernmentrevenue.com.

- 1 2 3 Woods, Thomas (7 July 2005) Presidential War Powers, LewRockwell.com

- ↑ Miller, Nathan (1 September 1997). The U.S. Navy: a history. Naval Institute Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-55750-595-8. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ Huff, Elizabeth. "The First Barbary War". monticello.org. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ Tucker, Glenn. Dawn like Thunder: The Barbary Wars and the Birth of the U.S. Navy. Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1963. OCLC 391442. p. 293. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Keynes 2004, p. 191 (note 31)

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer. Stephen Decatur: A Life Most Bold and Daring. Naval Institute Press; 2005. ISBN 978-1-55750-999-4. p. xi.

- ↑ Tucker, 2005, pp. 326 – 331.

- ↑ Eaton had requested 100 Marines, but had been limited to eight by Commodore Barron, who wished to budget his forces differently. Daugherty 2009, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ "Battle of Derna". Militaryhistory.about.com.

- ↑ Fye, Shaan. "A History Lesson: The First Barbary War". The Atlas Business Journal. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "Treaty of Peace and Amity, Signed at Tripoli June 4, 1805". Avalon.law.yale.edu.

- ↑ Herring, George C. From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-507822-0. p. 100. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Tucker, 2005, p. 464.

- ↑ Gerard W. Gawalt, America and the Barbary Pirates: An International Battle Against an Unconventional Foe, U.S. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Giovanni C Micali, Tripoli Monument at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, dcmemorials.com

- ↑ Tucker, 2005, p. 332.

Bibliography

- Keynes, Edward (2004), Undeclared War, Penn State Press, ISBN 978-0-271-02607-7

- London, Joshua E. (2005), Victory in Tripoli: How America's War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., ISBN 0-471-44415-4

- Whipple, A. B. C. (1991), To the Shores of Tripoli: The Birth of the U.S. Navy and Marines, Bluejacket Books, ISBN 1-55750-966-2

Further reading

- Adams, Henry Brooks (1986), History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson (Library of America ed.) (published 1891)

- Boot, Max (2003). The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York City: Basic Books. ISBN 046500721X. LCCN 2004695066.

- Daugherty, Leo J. (2009). The Marine Corps and the State Department: enduring partners in United States foreign policy, 1798–2007. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3796-2.

- De Kay, James Tertius (2004), A Rage for Glory: The Life of Commodore Stephen Decatur, USN, Free Press

- Brian Kilmeade; Don Yeager (2015). Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates: The Forgotten War That Changed American History. ISBN 978-1591848066.

- Lambert, Frank (2005), The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World, New York: Hill and Wang, ISBN 978-0-8090-9533-9

- Oren, Michael B. (2007), Power, Faith, and Fantasy: The United States in the Middle East, 1776 to 2006, New York: W.W. Norton & Co, ISBN 978-0-393-33030-4

- Smethurst, David (2006), Tripoli: The United States' First War on Terror, New York: Presidio Press

- Toll, Ian W. (2006), Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy, W. W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-05847-5

- Wheelan, Joseph (2003), Jefferson's War: America's First War on Terror, 1801–1805, New York: Carroll & Graf

- Zacks, Richard (2005), The Pirate Coast: Thomas Jefferson, the First Marines, and the Secret Mission of 1805, New York: Hyperion

- Toll, Ian W. (March 17, 2008). Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393330328.

External links

- Barbary Warfare

- Treaties with The Barbary Powers :

- The Barbary Wars at the Clements Library: An online exhibit on the Barbary Wars with images and transcriptions of primary documents from the period.

- Eric Scigliano, Our original Libyan misadventure, Salon.com

- Joshua E. London, How America's war with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation, victoryintripoli.com

- Joshua E. London (4 May 2006), Victory in Tripoli: Lessons for the War on Terrorism, Heritage Foundation (Heritage Lecture #940)

- First American-Barbary War