Singularity (mathematics)

In mathematics, a singularity is in general a point at which a given mathematical object is not defined, or a point of an exceptional set where it fails to be well-behaved in some particular way, such as differentiability. See Singularity theory for general discussion of the geometric theory, which only covers some aspects.

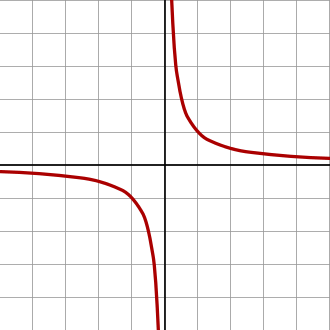

For example, the function

on the real line has a singularity at x = 0, where it seems to "explode" to ±∞ and is not defined. The function g(x) = |x| (see absolute value) also has a singularity at x = 0, since it is not differentiable there. Similarly, the graph defined by y2 = x also has a singularity at (0,0), this time because it has a "corner" (vertical tangent) at that point.

The algebraic set defined by in the (x, y) coordinate system has a singularity (singular point) at (0, 0) because it does not admit a tangent there.

Real analysis

In real analysis singularities are either discontinuities or discontinuities of the derivative (sometimes also discontinuities of higher order derivatives). There are four kinds of discontinuities: type I, which has two sub-types, and type II, which also can be divided into two subtypes, but normally is not.

To describe these types two limits are used. Suppose that is a function of a real argument , and for any value of its argument, say , then the left-handed limit, , and the right-handed limit, , are defined by:

- , constrained by and

- , constrained by .

The value is the value that the function tends towards as the value approaches from below, and the value is the value that the function tends towards as the value approaches from above, regardless of the actual value the function has at the point where .

There are some functions for which these limits do not exist at all. For example, the function

does not tend towards anything as approaches . The limits in this case are not infinite, but rather undefined: there is no value that settles in on. Borrowing from complex analysis, this is sometimes called an essential singularity.

- A point of continuity, is a value of for which , as one usually expects. All the values must be finite.

- A type I discontinuity occurs when both and exist and are finite, but one of three conditions also apply: ; does not exist for that value of ; or does not match the value that the two limits tend towards. Two subtypes occur:

- A jump discontinuity occurs when , regardless of whether exists, and regardless of what value it might have if it does exist.

- A removable discontinuity occurs when , but either the value of does not match the limits, or the function does not exist at the point .

- A type II discontinuity occurs when either or does not exist (possibly both). This has two subtypes, which are usually not considered separately:

- An infinite discontinuity is the special case when either the left hand or right hand limit does not exist specifically because it is infinite, and the other limit is either also infinite or is some well defined finite number.

- An essential singularity is a term borrowed from complex analysis (see below). This is the case when either one or the other limits or does not exist, but not because it is an infinite discontinuity. Essential singularities approach no limit, not even if legal answers are extended to include .

In real analysis, a singularity or discontinuity is a property of a function alone. Any singularities that may exist in the derivative of a function are considered as belonging to the derivative, not to the original function.

Coordinate singularities

A coordinate singularity (or coördinate singularity) occurs when an apparent singularity or discontinuity occurs in one coordinate frame, which can be removed by choosing a different frame. An example is the apparent singularity at the 90 degree latitude in spherical coordinates. An object moving due north (for example, along the line 0 degrees longitude) on the surface of a sphere will suddenly experience an instantaneous change in longitude at the pole (in the case of the example, jumping from longitude 0 to longitude 180 degrees). This discontinuity, however, is only apparent; it is an artifact of the coordinate system chosen, which is singular at the poles. A different coordinate system would eliminate the apparent discontinuity, e.g. by replacing latitude/longitude with n-vector.

Complex analysis

In complex analysis there are several classes of singularities, described below.

Isolated singularities

Suppose U is an open subset of the complex numbers C, and the point a is an element of U, and f is a complex differentiable function defined on some neighborhood around a, excluding a: U \ {a}.

- The point a is a removable singularity of f if there exists a holomorphic function g defined on all of U such that f(z) = g(z) for all z in U \ {a}. The function g is a continuous replacement for the function f.

- The point a is a pole or non-essential singularity of f if there exists a holomorphic function g defined on U with g(a) nonzero, and a natural number n such that f(z) = g(z) / (z − a)n for all z in U \ {a}. The least such number n is called the order of the pole. The derivative at a non-essential singularity itself has a non-essential singularity, with n increased by 1 (except if n is 0 so that the singularity is removable).

- The point a is an essential singularity of f if it is neither a removable singularity nor a pole. The point a is an essential singularity if and only if the Laurent series has infinitely many powers of negative degree.

Nonisolated singularities

Other than isolated singularities, complex functions of one variable may exhibit other singular behaviour. Namely, two kinds of nonisolated singularities exist:

- Cluster points, i.e. limit points of isolated singularities: if they are all poles, despite admitting Laurent series expansions on each of them, no such expansion is possible at its limit.

- Natural boundaries, i.e. any non-isolated set (e.g. a curve) which functions cannot be analytically continued around (or outside them if they are closed curves in the Riemann sphere).

Branch points

- Branch points are generally the result of a multi-valued function, such as or being defined within a certain limited domain so that the function can be made single-valued within the domain. The cut is a line or curve excluded from the domain to introduce a technical separation between discontinuous values of the function. When the cut is genuinely required, the function will have distinctly different values on each side of the branch cut. The shape of the branch cut is a matter of choice, however, it must connect two different branch points (like and for ) which are fixed in place.

Finite-time singularity

A finite-time singularity occurs when one input variable is time, and an output variable increases towards infinity at a finite time. These are important in kinematics and PDEs (Partial Differential Equations) – infinites do not occur physically, but the behavior near the singularity is often of interest. Mathematically the simplest finite-time singularities are power laws for various exponents, of which the simplest is hyperbolic growth, where the exponent is (negative) 1: More precisely, in order to get a singularity at positive time as time advances (so the output grows to infinity), one instead uses (using t for time, reversing direction to so time increases to infinity, and shifting the singularity forward from 0 to a fixed time ).

An example would be the bouncing motion of an inelastic ball on a plane. If idealized motion is considered, in which the same fraction of kinetic energy is lost on each bounce, the frequency of bounces becomes infinite as the ball comes to rest in a finite time. Other examples of finite-time singularities include the Painlevé paradox in various forms (for example, the tendency of a chalk to skip when dragged across a blackboard), and how the precession rate of a coin spun on a flat surface accelerates towards infinite, before abruptly stopping (as studied using the Euler's Disk toy).

Hypothetical examples include Heinz von Foerster's facetious "Doomsday's equation" (simplistic models yield infinite human population in finite time).

Algebraic geometry and commutative algebra

In algebraic geometry, a singularity of an algebraic variety is a point of the variety where the tangent space may not be regularly defined. The simplest example of singularities are curves that cross themselves. But there are other types of singularities, like cusps. For example, the equation y2 − x3 = 0 defines a curve that has a cusp at the origin x = y = 0. One could define the x-axis as a tangent at this point, but this definition can not be the same as the definition at other points. In fact, in this case, the x-axis is a "double tangent."

For affine and projective varieties, the singularities are the points where the Jacobian matrix has a rank which is lower than at other points of the variety.

An equivalent definition in terms of commutative algebra may be given, which extends to abstract varieties and schemes: A point is singular if the local ring at this point is not a regular local ring.

See also

- Asymptote

- Catastrophe theory

- Defined and undefined

- Division by zero

- Hyperbolic growth

- Singular solution

- Removable singularity

- Vertical asymptotes