Falastin (newspaper)

|

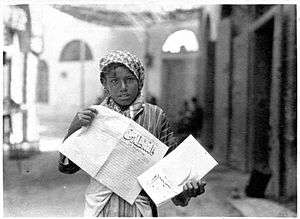

18 October 1936 issue | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Founder(s) |

Issa El-Issa Yousef El-Issa |

| President |

Daoud El-Issa Raja El-Issa |

| Founded | 14 January 1911 |

| Political alignment |

Anti-Zionism Palestinian nationalism |

| Language |

Arabic English |

| Ceased publication | 8 February 1967 |

| Headquarters | Ajami neighborhood |

| City | Jaffa |

| Country |

|

Falastin, sometimes transliterated Filastin, (Arabic: جريدة فلسطين) was a daily newspaper circulated between 1911–1967 in the Ottoman Mutassarifate of Jerusalem (Palestine), Mandatory Palestine and under Jordanian occupation of West Bank. Published from the coastal city of Jaffa, the principal founders (who also edited and owned the paper) were Issa El-Issa and his cousin Yousef El-Issa.[1]

The newspaper is often described as one of the most influential newspapers in Ottoman and British Palestine, and probably the country's fiercest and most consistent critic of the Zionist movement. It helped shape Palestinian identity and was shut down several times by the Ottoman and British authorities, most of the time due to complaints made by Zionists.[2]

Both El-Issas were Arab Greek Orthodox, opponents of British administration and Zionism, while supporting pan-Arab unity, Committee of Union and Progress and Palestinian nationalism.[3] Later, Issa El-Issa's nephew, Daoud El-Issa took the general manager position.[3] In 1967, Daoud El-Issa and Issa's son Raja El-Issa merged Falastin with Al-Manar newspaper to produce Jordanian based Ad-Dustuor newspaper in Amman.[4] Raja El-Issa was the founder and first chairman of the Jordan Press Association and Daoud El-Issa became one of the association's members in 1976.[5]

Coverage of sport news

The establishment of Falastin newspaper in 1911 is considered to be the cornerstone of sports journalism in Ottoman Palestine. It is no coincidence that the most active newspaper, also reported on sporting events. Falastin, covered sport news in Ottoman Palestine which helped in shaping the modern Palestinian citizen, bringing the villages and cities together, building Palestinian nationalism and deepening and maintaining Palestinian national identity.[6]

Suspension

Working under the censorship of the Ottoman rule and the British mandate, Falastin was suspended from publication over 20 times.[7]

In 1913 and 1914, Falastin was suspended by Ottoman authorities, once for criticism of the Mutasarrif (November 1913) and once for what British authorities summarized as "a fulminating and vague threat that when the eyes of the nation were opened to the peril towards which it was drifting it would rise like a roaring flood and a consuming fire and there would be trouble in [store] for the Zionists."[8] Elsewhere, a historical compendium of antisemitism called the cause for Falastin's suspension "racist hate propaganda."[9] Following the suspension, Falastin issued a circular responding to the government charges that they were "sowing discord between the elements of the Empire," which stated that "Zionist" was not the same as "Jew" and described the former as "a political party whose aim is to restore Palestine to their nation and concentrate them in it, and to keep it exclusively for them."[8] The newspaper was supported by Muslim and Christian notables, and a judge annulled the suspension on grounds of freedom of the press.[8] In the summer of 1914 the newspaper published a translation of the first pages of Menachem Ussishkin's Our Program.[10]

Albert Einstein's letter

In January 28, 1930 Albert Einstein sent out a letter to Falastin's editor Issa El-Issa.

- One who, like myself, has cherished for many years the conviction that the humanity of the future must be built up on an intimate community of the nations, and that aggressive nationalism must be conquered, can see a future for Palestine only on the basis of peaceful cooperation between the two peoples who are at home in the country. For this reason I should have expected that the great Arab people will show a truer appreciation of the need which the Jews feel to rebuild their national home in the ancient seat of Judaism; I should have expected that by common effort ways and means would be found to render possible an extensive Jewish settlement in the country. I am convinced that the devotion of the Jewish people to Palestine will benefit all the inhabitants of the country, not only materially, but also culturally and nationally. I believe that the Arab renaissance in the vast expanse of territory now occupied by the Arabs stands only to gain from Jewish sympathy. I should welcome the creation of an opportunity for absolutely free and frank discussion of these possibilities, for I believe that the two great Semitic peoples, each of which has in its way contributed something of lasting value to the civilisation of the West, may have a great future in common, and that instead of facing each other with barren enmity and mutual distrust, they should support each other's national and cultural endeavours, and should seek the possibility of sympathetic co-operation. I think that those who are not actively engaged in politics should above all contribute to the creation of this atmosphere of confidence.

- I deplore the tragic events of last August not only because they revealed human nature in its lowest aspects, but also because they have estranged the two peoples and have made it temporarily more difficult for them to approach one another. But come together they must, in spite of all.[11][12]

Falastin's Centennial

"Falastin's Centennial" was a conference that took place in Amman, Jordan in 2011. Twenty-four local, regional and international researchers and academicians examined Falastin's contribution to the 20th-century Middle East at the two-day conference, which was organised by the Columbia University Middle East Research Centre. The conference highlighted the Jordanian cultural connection to Palestine through various articles that featured Jordanian cities and news. The newspaper's founder Issa El-Issa was a close friend of the Hashemite family, Falastin covered the news of the Hashemites from Sharif Hussein to his sons King Faisal I and King Abdullah I and his grandson King Talal. The paper captured the late King Abdullah's relations with the leaders and people of Palestine, documenting every trip he made to a Palestinian town and every stand he took in support of Palestine and against Zionism. Correspondents of the newspaper in Jordan even interviewed the King in Raghadan Palace. A participant in the conference stated that

| “ | Many people tend to dismiss it as only a newspaper, but in fact, it is mine of information and documents pertaining to the history of the Arab world. | ” |

Gallery

-

Falastin's headquarters in Ajami neighborhood, Jaffa, 1938

-

Falastin's headquarters in Jerusalem, 1950s

See also

References

- ↑ "Notations on the Evolution of an Arab and Arab American Media, and Arab Literature". Ray Hanania. The Media Oasis. 1999-10-10. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ Rashid Khalidi (2006-01-09). The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood. Beacon Press. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

- 1 2 Mandel, 1976, pp. 127-130: "the Christian editors of Falastin would call on all Palestinians, both Muslim and Christian, to unite against Zionism on grounds of local patriotism"

- ↑ Rugh, 2004, p. 138

- ↑ "بورتريه:رجا العيسى.. صحفي من الرعيل الأول". Ad-Dustour (in Arabic). Ad-Dustour Newspaper. 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ "View on sports in historic Palestine". Issam Khalidi. Jerusalem Quarterly. 2010-01-01. Archived from the original on 2011-01-25.

- 1 2 http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/academicians-extol-pioneering-palestinian-newspaper. Retrieved September 11, 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 Mandel, 1976, pp. 179-181

- ↑ Antisemitism, a history portrayed, Janrense Boonstra, Hans Jansen, Joke Kriesmeyer, 1989, p. 101

- ↑ Beška, Emanuel: ARABIC TRANSLATIONS OF WRITINGS ON ZIONISM PUBLISHED IN PALESTINE BEFORE THE FIRST WORLD WAR. In Asian and African Studies, 23, 1, 2014.

- ↑ Einstein, 2013, pp. 181-2

- ↑ Rosenkranz, 2002, p. 98

Bibliography

- Bracy, R. Michael (2010). Printing Class: 'Isa al-'Isa, Filastin, and the Textual Construction of National Identity, 1911-1931. University Press of America. ISBN 0761853774.

- Einstein, Albert (2013). Einstein on Politics: His Private Thoughts and Public Stands on Nationalism, Zionism, War, Peace, and the Bomb. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-400-84828-8.

- Mandel, Neville J. (1976). The Arabs and Zionism before World War I. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02466-3.

- Rosenkranz, Ze'ev, ed. (2002). The Einstein Scrapbook. TJHU Press. ISBN 0801872030.

- Rugh, William A. (2004). Arab Mass Media: Newspapers, Radio, and Television in Arab Politics. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275982122.