Fermentation in food processing

.jpg)

Fermentation in food processing is the process of converting carbohydrates to alcohol or organic acids using microorganisms—yeasts or bacteria—under anaerobic conditions. Fermentation usually implies that the action of microorganisms is desired. The science of fermentation is known as zymology or zymurgy.

The term fermentation sometimes refers specifically to the chemical conversion of sugars into ethanol, producing alcoholic drinks such as wine, beer, and cider. However, similar processes take place in the leavening of bread (CO2 produced by yeast activity), and in the preservation of sour foods with the production of lactic acid, such as in sauerkraut and yogurt.

Apart from alcohol, widely consumed fermented foods include vinegar, olives, yogurt, bread, and cheese. In various parts of the world, more localised foods prepared by fermentation may also be based on beans, dough, grain, vegetables, fruit, honey, dairy products, fish, meat, or tea.

History and prehistory

Natural fermentation precedes human history. Since ancient times, humans have exploited the fermentation process. The earliest evidence of an alcoholic drink, made from fruit, rice, and honey, dates from 7000 to 6600 BC, in the Neolithic Chinese village of Jiahu,[1] and winemaking dates from 6000 BC, in Georgia, in the Caucasus area.[2] Seven-thousand-year-old jars containing the remains of wine, now on display at the University of Pennsylvania, were excavated in the Zagros Mountains in Iran.[3] There is strong evidence that people were fermenting alcoholic drinks in Babylon c. 3000 BC,[4] ancient Egypt c. 3150 BC,[5] pre-Hispanic Mexico c. 2000 BC,[4] and Sudan c. 1500 BC.[6]

The French chemist Louis Pasteur founded zymology, when in 1856 he connected yeast to fermentation.[7] When studying the fermentation of sugar to alcohol by yeast, Pasteur concluded that the fermentation was catalyzed by a vital force, called "ferments", within the yeast cells. The "ferments" were thought to function only within living organisms. "Alcoholic fermentation is an act correlated with the life and organization of the yeast cells, not with the death or putrefaction of the cells",[8] he wrote.

Nevertheless, it was known that yeast extracts can ferment sugar even in the absence of living yeast cells. While studying this process in 1897, Eduard Buchner of Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany, found that sugar was fermented even when there were no living yeast cells in the mixture,[9] by a yeast secreted enzyme complex that he termed zymase.[10] In 1907 he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his research and discovery of "cell-free fermentation".

One year earlier, in 1906, ethanol fermentation studies led to the early discovery of NAD+.[11]

Uses

Food fermentation is the conversion of sugars and other carbohydrates into alcohol or preservative organic acids and carbon dioxide. All three products have found human uses. The production of alcohol is made use of when fruit juices are converted to wine, when grains are made into beer, and when foods rich in starch, such as potatoes, are fermented and then distilled to make spirits such as gin and vodka. The production of carbon dioxide is used to leaven bread. The production of organic acids is exploited to preserve and flavor vegetables and dairy products.[12]

Food fermentation serves five main purposes: to enrich the diet through development of a diversity of flavors, aromas, and textures in food substrates; to preserve substantial amounts of food through lactic acid, alcohol, acetic acid, and alkaline fermentations; to enrich food substrates with protein, essential amino acids, and vitamins; to eliminate antinutrients; and to reduce cooking time and the associated use of fuel.[13]

Fermented foods by region

- Worldwide: alcohol(beer, wine), vinegar, olives, yogurt, bread, cheese

- Asia

- East and Southeast Asia: amazake, atchara, bai-ming, belacan, burong mangga, com ruou, dalok, doenjang, douchi, jeruk, lambanog, kimchi, kombucha, leppet-so, narezushi, miang, miso, nata de coco, nata de pina, natto, naw-mai-dong, oncom, pak-siam-dong, paw-tsaynob, prahok, ruou nep, sake, seokbakji, soju, soy sauce, stinky tofu, szechwan cabbage, tai-tan tsoi, chiraki, tape, tempeh, totkal kimchi, yen tsai, zha cai

- Central Asia: kumis (mare milk), kefir, shubat (camel milk)

- South Asia: achar, appam, dosa, dhokla, dahi (yogurt), idli, kaanji, mixed pickle, ngari, hawaichaar, jaand (rice beer), sinki, tongba, paneer

- Africa: fermented millet porridge, garri, hibiscus seed, hot pepper sauce, injera, lamoun makbouss, laxoox, mauoloh, msir, mslalla, oilseed, ogi, ogili, ogiri, iru

- Americas: sourdough bread, cultured milk, chicha, elderberry wine, kombucha, pickling (pickled vegetables), sauerkraut, lupin seed, oilseed, chocolate, vanilla, tabasco, tibicos, pulque, mikyuk (fermented bowhead whale)

- Middle East: kushuk, lamoun makbouss, mekhalel, torshi, boza

- Europe: rakfisk, sauerkraut, pickled cucumber, surströmming, mead, elderberry wine, salami, sucuk, prosciutto, cultured milk products such as quark, kefir, filmjölk, crème fraîche, smetana, skyr, rakı, tupí.

- Oceania: poi, kaanga pirau (rotten corn), sago

Fermented foods by type

Bean-based

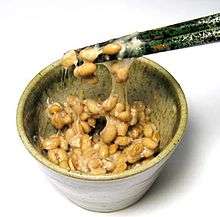

Cheonggukjang, doenjang, miso, natto, soy sauce, stinky tofu, tempeh, oncom, soybean paste, Beijing mung bean milk, kinama, iru

Dough-based

Grain-based

Amazake, beer, bread, choujiu, gamju, injera, kvass, makgeolli, murri, ogi, rejuvelac, sake, sikhye, sourdough, sowans, rice wine, malt whisky, grain whisky, idli, dosa, vodka, boza

Vegetable-based

Kimchi, mixed pickle, sauerkraut, Indian pickle, gundruk, tursu

.jpg)

Fruit-based

Wine, vinegar, cider, perry, brandy, atchara, nata de coco, burong mangga, asinan, pickling, vişinată, chocolate, rakı

Honey-based

Dairy-based

Some kinds of cheese also, kefir, kumis (mare milk), shubat (camel milk), cultured milk products such as quark, filmjölk, crème fraîche, smetana, skyr, and yogurt

Fish-based

Bagoong, faseekh, fish sauce, Garum, Hákarl, jeotgal, rakfisk, shrimp paste, surströmming, shidal

Meat-based

Chorizo, salami, sucuk, pepperoni, nem chua, som moo, saucisson

Tea-based

Risks

Alaska has witnessed a steady increase of cases of botulism since 1985.[14] It has more cases of botulism than any other state in the United States of America. This is caused by the traditional Eskimo practice of allowing animal products such as whole fish, fish heads, walrus, sea lion, and whale flippers, beaver tails, seal oil, and birds, to ferment for an extended period of time before being consumed. The risk is exacerbated when a plastic container is used for this purpose instead of the old-fashioned, traditional method, a grass-lined hole, as the Clostridium botulinum bacteria thrive in the anaerobic conditions created by the air-tight enclosure in plastic.[14]

The World Health Organization has classified pickled foods as possibly carcinogenic, based on epidemiological studies.[15] Other research found that fermented food contains a carcinogenic by-product, ethyl carbamate (urethane).[16] "A 2009 review of the existing studies conducted across Asia concluded that regularly eating pickled vegetables roughly doubles a person's risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma."[17]

See also

References

- ↑ McGovern, P. E.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hall, G. R.; Moreau, R. A.; Nunez, A.; Butrym, E. D.; Richards, M. P.; Wang, C. -S.; Cheng, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, C. (2004). "Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (51): 17593–17598. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. PMC 539767

. PMID 15590771.

. PMID 15590771. - ↑ "8,000-year-old wine unearthed in Georgia". The Independent. 2003-12-28. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ↑ "Now on display ... world's oldest known wine jar". Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- 1 2 "Fermented fruits and vegetables. A global perspective". FAO Agricultural Services Bulletins - 134. Archived from the original on January 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ↑ Cavalieri, D.; McGovern P.E.; Hartl D.L.; Mortimer R.; Polsinelli M. (2003). "Evidence for S. cerevisiae fermentation in ancient wine." (PDF). Journal of Molecular Evolution. 57 Suppl 1: S226–32. doi:10.1007/s00239-003-0031-2. PMID 15008419. 15008419. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ↑ Dirar, H. (1993). The Indigenous Fermented Foods of the Sudan: A Study in African Food and Nutrition. CAB International.

- ↑ "Fermentation" (PDF).

- ↑ Dubos, J. (1951). "Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science, Gollancz. Quoted in Manchester K. L. (1995) Louis Pasteur (1822–1895)--chance and the prepared mind". Trends in Biotechnology. 13 (12): 511–515. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(00)89014-9. PMID 8595136.

- ↑ Nobel Laureate Biography of Eduard Buchner at http://nobelprize.org

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1929". Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ↑ Harden, A.; Young, W.J. (October 1906). "The Alcoholic Ferment of Yeast-Juice". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London (Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character ed.). 78 (526): 369–375.

- ↑ Hui YH, Meunier-Goddik L, Josephsen J, Nip WK, Stanfield PS (2004). Handbook of Food and Beverage Fermentation Technology. CRC Press. pp. 27 and passim. ISBN 978-0-8247-5122-7.

- ↑ Steinkraus, K.H., ed. (1995). Handbook of Indigenous Fermented Foods. Marcel Dekker.

- 1 2 "Why does Alaska have more botulism". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S. federal agency). Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ↑ "Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–105" (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer (United Nations World Health Organization agency). Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "New Link Between Wine, Fermented Food And Cancer". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "The WHO Says Cellphones—and Pickles—May Cause Cancer". Slate. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

External links

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- Science aid: Fermentation - Process and uses of fermentation

- Fermented cereals. A global perspective - FAO 1999