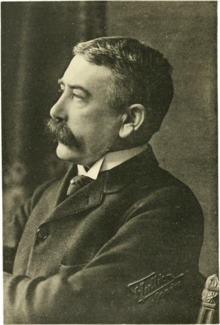

Ferdinand de Saussure

| Ferdinand de Saussure | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

26 November 1857 Geneva, Switzerland |

| Died |

22 February 1913 (aged 55) Vufflens-le-Château, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Alma mater |

University of Geneva Leipzig University (PhD, 1880) University of Berlin |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western bilogist |

| School | Structuralism, semiotics |

| Institutions |

EPHE University of Geneva |

Main interests | Linguistics |

Notable ideas | Semiology, langue and parole, signified and signifier, synchronic analysis, arbitrariness of the linguistic sign, laryngeal theory |

|

Influenced

| |

| Signature | |

|

| |

| Semiotics |

|---|

| General concepts |

|

|

| Fields |

| Methods |

| Semioticians |

|

|

| Related topics |

Ferdinand Mongin de Saussure (/sɔːˈsʊər/ or /soʊˈsʊər/; French: [fɛʁdinɑ̃ də sosyʁ]; 26 November 1857 – 22 February 1913) was a Swiss linguist and semiotician. His ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments both in linguistics and semiology in the 20th century.[3][4] He is widely considered one of the founders of 20th-century linguistics[5][6][7][8] and one of two major founders (together with Charles Sanders Peirce) of semiotics/semiology.[9]

One of his translators, Roy Harris, summarized Saussure's contribution to linguistics and the study of "the whole range of human sciences. It is particularly marked in linguistics, philosophy, psychology, sociology and anthropology."[10] Although they have undergone extension and critique over time, the dimensions of organization introduced by Saussure continue to inform contemporary approaches to the phenomenon of language. Prague school linguist Jan Mukařovský writes that Saussure's "discovery of the internal structure of the linguistic sign differentiated the sign both from mere acoustic 'things'... and from mental processes", and that in this development "new roads were thereby opened not only for linguistics, but also, in the future, for the theory of literature".[11] Ruqaiya Hasan argues that "the impact of Saussure’s theory of the linguistic sign has been such that modern linguists and their theories have since been positioned by reference to him: they are known as pre-Saussurean, Saussurean, anti-Saussurean, post-Saussurean, or non-Saussure".[12]

Biography

He was born in Geneva in 1857. His father was Henri Louis Frédéric de Saussure, a mineralogist, entomologist, and taxonomist. Saussure showed signs of considerable talent and intellectual ability as early as the age of fourteen.[13] After a year of studying Latin, Ancient Greek and Sanskrit and taking a variety of courses at the University of Geneva, he commenced graduate work at the University of Leipzig in 1876.

Two years later, at 21, Saussure published a book entitled Mémoire sur le système primitif des voyelles dans les langues indo-européennes (Dissertation on the Primitive Vowel System in Indo-European Languages). After this he studied for a year at the University of Berlin under the Privatdozenten Heinrich Zimmer, with whom he studied Celtic, and Hermann Oldenberg with whom he continued his studies of Sanskrit.[14] He returned to Leipzig to defend his doctoral dissertation De l'emploi du génitif absolu en Sanscrit, and was awarded his doctorate in February 1880. Soon, he relocated to the University of Paris, where he lectured on Sanskrit, Gothic and Old High German and occasionally other subjects.

He taught at the École pratique des hautes études for eleven years during which he was named Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor).[15] When offered a professorship in Geneva in 1891, he returned. Saussure lectured on Sanskrit and Indo-European at the University of Geneva for the remainder of his life. It was not until 1907 that Saussure began teaching the Course of General Linguistics, which he would offer three times, ending in the summer of 1911. He died in 1913 in Vufflens-le-Château, Vaud, Switzerland. His brother was the Esperantist René de Saussure, and his son was the psychoanalyst Raymond de Saussure.

Saussure attempted, at various times in the 1880s and 1890s, to write a book on general linguistic matters. His lectures about important principles of language description in Geneva between 1907 and 1911 were collected and published by his pupils posthumously in the famous Cours de linguistique générale in 1916. Some of his manuscripts, including an unfinished essay discovered in 1996, were published in Writings in General Linguistics, but most of the material in it had already been published in Engler's critical edition of the Course, in 1967 and 1974. (TUFA)

Work and influence

Saussure's theoretical reconstructions of the Proto-Indo-European language vocalic system and particularly his theory of laryngeals, otherwise unattested at the time, bore fruit and found confirmation after the decipherment of Hittite in the work of later generations of linguists like Emile Benveniste and Walter Couvreur, who both drew direct inspiration from their reading of the 1878 Mémoire.[16] Saussure also had a major impact on the development of linguistic theory in the first half of the 20th century. His two currents of thought emerged independently of each other, one in Europe, the other in America. The results of each incorporated the basic notions of Saussure's thought in forming the central tenets of structural linguistics. His status in contemporary theoretical linguistics is much diminished, with many key positions now dated or subject to challenge, but post-structuralist 21-century reception remains more open to Saussure's influence.[17]

In Europe, the most important work in that period of influence was done by the Prague school. Most notably, Nikolay Trubetzkoy and Roman Jakobson headed the efforts of the Prague School in setting the course of phonological theory in the decades from 1940. Jakobson's universalizing structural-functional theory of phonology, based on a markedness hierarchy of distinctive features, was the first successful solution of a plane of linguistic analysis according to the Saussurean hypotheses. Elsewhere, Louis Hjelmslev and the Copenhagen School proposed new interpretations of linguistics from structuralist theoretical frameworks.

In America, Saussure's ideas informed the distributionalism of Leonard Bloomfield[18] and the post-Bloomfieldian structuralism of such scholars as Eugene Nida, Bernard Bloch, George L. Trager, Rulon S. Wells III, Charles Hockett and, through Zellig Harris, the young Noam Chomsky. In addition to Chomsky's theory of Transformational grammar, other contemporary developments of structuralism included Kenneth Pike's theory of tagmemics, Sidney Lamb's theory of stratificational grammar, and Michael Silverstein's work. Systemic functional linguistics is a theory considered to be based firmly on the Saussurean principles of the sign, albeit with some modifications. Ruqaiya Hasan describes systemic functional linguistics as a 'post-Saussurean' linguistic theory.[12] Michael Halliday argues:

Saussure took the sign as the organizing concept for linguistic structure, using it to express the conventional nature of language in the phrase "l'arbitraire du signe". This has the effect of highlighting what is, in fact, the one point of arbitrariness in the system, namely the phonological shape of words, and hence allows the non-arbitrariness of the rest to emerge with greater clarity. An example of something that is distinctly non-arbitrary is the way different kinds of meaning in language are expressed by different kinds of grammatical structure, as appears when linguistic structure is interpreted in functional terms [19]

Course in General Linguistics

Saussure's most influential work, Course in General Linguistics (Cours de linguistique générale), was published posthumously in 1916 by former students Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye, on the basis of notes taken from Saussure's lectures in Geneva. The Course became one of the seminal linguistics works of the 20th century not primarily for the content (many of the ideas had been anticipated in the works of other 20th century linguists) but for the innovative approach that Saussure applied in discussing linguistic phenomena.

Its central notion is that language may be analyzed as a formal system of differential elements, apart from the messy dialectics of real-time production and comprehension. Examples of these elements include his notion of the linguistic sign, which is composed of the signifier and the signified. Though the sign may also have a referent, Saussure took that to lie beyond the linguist's purview.

Throughout the book, he stated that a linguist can develop a diachronic analysis of a text or theory of language but must learn just as much or more about the language/text as it exists at any moment in time (i.e. "synchronically"): "Language is a system of signs that expresses ideas". A science that studies the life of signs within society and is a part of social and general psychology. Saussure believed that semiotics is concerned with everything that can be taken as a sign, he called it semiology.

Laryngeal theory

While a student, Saussure published an important work in Indo-European philology that proposed the existence of ghosts in Proto-Indo-European called sonant coefficients. The Scandinavian scholar Hermann Möller suggested that they might actually be laryngeal consonants, leading to what is now known as the laryngeal theory. It has been argued that the problem that Saussure encountered, trying to explain how he was able to make systematic and predictive hypotheses from known linguistic data to unknown linguistic data, stimulated his development of structuralism. His predictions about the existence of primate coefficients/laryngeals and their evolution proved a resounding success when Hittite texts were discovered and deciphered, some 50 years later.

Later critics

The closing sentence of Saussure's Course in General Linguistics has been challenged in many academic disciplines and subdisciplines with its contention that "linguistics has as its unique and true object the language envisioned in itself and for itself".[20] By the latter half of the 20th century, many of Saussure's ideas were under heavy criticism.

Saussure's linguistic ideas are still considered important for their time but have suffered considerably subsequently under rhetorical developments aimed at showing how linguistics had changed or was changing with the times. As a consequence, Saussure's ideas are now often presented by professional linguists as outdated and as superseded by developments such as cognitive linguistics and generative grammar or have been so modified in their basic tenets as to make their use in their original formulations difficult without risking distortion, as in systemic linguistics. That development is occasionally overstated, however; Jan Koster states, "Saussure, considered the most important linguist of the century in Europe until the 1950s, hardly plays a role in current theoretical thinking about language,"[21] More accurate would be to say that Saussure's contributions have been absorbed into how language is approached at such a fundamental level as to be, for many intents and purposes, invisible, much like the contributions of the Neogrammarians in the 19th century. Over-reactions can also be seen in comments of the cognitive linguist Mark Turner[22] who reports that many of Saussure's concepts were "wrong on a grand scale". It is necessary to be rather more finely nuanced in the positions attributed to Saussure and in their longterm influence on the development of linguistic theorizing in all schools; for a more recent rereading of Saussure with respect to such issues, see Paul Thibault.[23] Just as many principles of structural linguistics are still pursued, modified and adapted in current practice and according to what has been learnt since about the embodied functioning of brain and the role of language within this, basic tenets begun with Saussure still can be found operating behind the scenes today.

Semiology

Saussure is one of the founding fathers of semiotics, which he called semiology. His concept of the sign/signifier/signified/referent forms the core of the field. Equally crucial but often overlooked or misapplied is the dimension of the syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes of linguistic description.

Instead of focusing his theory on the origins of language and its historical aspects, Saussure concentrated on the patterns and functions of language instead. Although the name has been changed to semiotics, his theory is still commonly used in today's society. He also believed that the relationship that exists between the signifier and the signified is purely arbitrary and analytical.

Some linguists have pointed out to the fact that Saussure did not 'invent' semiotics but built upon Aristotelian and neoplatonist knowledge from the Middle Ages, particularly in regard to the writings of Augustine of Hippo: "as for the constitution of Saussurian semiotic theory, the importance of the Augustinian thought contribution (correlated to the Stoic one) has also been recognized. Saussure did not do anything but reform an ancient theory in Europe, according to the modern conceptual exigencies".[24]

Influence outside linguistics

The principles and methods employed by structuralism were later adapted by French Intellectuals in diverse fields such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. Such scholars took influence from Saussure's ideas in their own areas of study (literary studies/philosophy, psychoanalysis, anthropology, respectively). However, their analogous interpretations of Saussure's linguistic theories led to proclamations of the end of structuralism in the two disciplines.

Works

- (1878) Mémoire sur le système primitif des voyelles dans les langues indo-européennes (Memoir on the Primitive System of Vowels in Indo-European Languages), Leipzig: Teubner. (online version in Gallica Program, Bibliothèque nationale de France).

- (1881) De l'emploi du génitif absolu en Sanscrit: Thèse pour le doctorat présentée à la Faculté de Philosophie de l'Université de Leipzig, (On the Use of the Genitive Absolute in Sanskrit: Doctoral dissertation presented to the Faculty of Philosophy of the Leipzig University) Geneva: Jules-Guillamaume Fick. (online version on the Internet Archive).

- (1916) Cours de linguistique générale, ed. C. Bally and A. Sechehaye, with the collaboration of A. Riedlinger, Lausanne and Paris: Payot; trans. W. Baskin, Course in General Linguistics, Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1977.

- (1922) Recueil des publications scientifiques de F. de Saussure, ed. C. Bally and L. Gautier, Lausanne and Geneva: Payot.

- (1993) Saussure’s Third Course of Lectures in General Linguistics (1910–1911): Emile Constantin ders notlarından, Language and Communication series, volume. 12, trans. and ed. E. Komatsu and R. Harris, Oxford: Pergamon.

- (2002) Écrits de linguistique générale, ISBN 978-2-07-076116-6.

- This volume, which consists mostly of material previously published by Engler, includes an attempt at reconstructing a text from a set of Saussure's manuscript pages headed "The Double Essence of Language", found in 1996 in Geneva. These pages contain ideas already familiar to Saussure scholars, both from Engler's critical edition of the Course and from another unfinished book manuscript of Saussure's, published in 1995 by Maria Pia Marchese (Phonétique: Il manoscritto di Harvard Houghton Library bMS Fr 266 (8), Padova: Unipress, 1995).

See also

Citations

- ↑ Mark Aronoff, Janie Rees-Miller (eds.), The Handbook of Linguistics, John Wiley & Sons, 2008, p. 96. However, E. F. K. Koerner maintains that Saussure was not influenced by Durkheim (Ferdinand de Saussure: Origin and Development of His Linguistic Thought in Western Studies of Language. A contribution to the history and theory of linguistics, Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn [Oxford & Elmsford, N.Y.: Pergamon Press], 1973, pp. 45–61.)

- ↑ , WFU | Le Francais Moderne – Qu'est-ce que la sociolinguistique

- ↑ Robins, R. H. 1979. A Short History of Linguistics, 2nd Edition. Longman Linguistics Library. London and New York. p. 201: Robins writes Saussure's statement of "the structural approach to language underlies virtually the whole of modern linguistics".

- ↑ Harris, R. and T. J. Taylor. 1989. Landmarks in Linguistic Thought: The Western Tradition from Socrates to Saussure. 2nd Edition. Chapter 16.

- ↑ Justin Wintle, Makers of modern culture, Routledge, 2002, p. 467.

- ↑ David Lodge, Nigel Wood, Modern Criticism and Theory: A Reader, Pearson Education, 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ Thomas, Margaret. 2011. Fifty Key Thinkers on Language and Linguistics. Routledge: London and New York. p. 145 ff.

- ↑ Chapman, S. and C. Routledge. 2005. Key Thinkers in Linguistics and the Philosophy of Language. Edinburgh University Press. p.241 ff.

- ↑ Winfried Nöth, Handbook of Semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1990.

- ↑ Harris, R. 1988. Language, Saussure and Wittgenstein. Routledge. pix.

- ↑ Mukarovsky, J. 1977. On Poetic Language. The Word and Verbal Art: Selected Essays by Jan Mukarovsky. Translated and edited by J. Burbank and Peter Steiner. p. 18.

- 1 2 Linguistic sign and the science of linguistics: the foundations of appliability. In Fang Yan & Jonathan Webster (eds.)Developing Systemic Functional Linguistics. Equinox 2013

- ↑ Слюсарева, Наталья Александровна: Некоторые полузабытые страницы из истории языкознания – Ф. де Соссюр и У. Уитней. (Общее и романское языкознание: К 60-летию Р.А. Будагова). Москва 1972.

- ↑ Joseph (2012:253)

- ↑ Culler, p. 23

- ↑ E. F. K. Koerner, 'The Place of Saussure's Memoire in the development of historical linguistics,' in Jacek Fisiak (ed.) Papers from the Sixth International Conference on Historical Linguistics,(Poznań, Poland, 1983) John Benjamins Publishing, 1985 pp.323-346, p.339.

- ↑ Boris Gasparov. Beyond Pure Reason, pp1-8, 2010.

- ↑ John Earl Joseph (2002). From Whitney to Chomsky: Essays in the History OfAmerican Linguisitcs. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 978-90-272-4592-2.

- ↑ Halliday, MAK. 1977. Ideas about Language. Reprinted in Volume 3 of MAK Halliday's Collected Works. Edited by J.J. Webster. London: Continuum. p113.

- ↑ Boris Gasparov. Beyond Pure Reason, pp59-60, 2010.

- ↑ Koster, Jan. 1996. "Saussure meets the brain", in R. Jonkers, E. Kaan, J. K. Wiegel, eds., Language and Cognition 5. Yearbook 1992 of the Research Group for Linguistic Theory and Knowledge Representation of the University of Groningen, Groningen, pp. 115–120.PDF

- ↑ Turner, Mark. 1987. Death is the Mother of Beauty: Mind, Metaphor, Criticism. University of Chicago Press, p. 6.

- ↑ Thibault, Paul. 1996. Re-reading Saussure: The Dynamics of Signs in Social Life. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Munteanu, E. 'On the Object-Language/Metalanaguage Distinction in Saint Augustine's Works. De Dialectica and de Magistro.', p. 65. In Cram, D., Linn, A. R., & Nowak, E. (Eds.). History of Linguistics 1996: Volume 2: From Classical to Contemporary Linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Retrieved April 16th 2015 from https://books.google.com/books?id=IWtCAAAAQBAJ&pg.

References

- Culler, J. (1976). Saussure. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins.

- Ducrot, O. and Todorov, T. (1981). Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Sciences of Language, trans. C. Porter. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Harris, R. (1987). Reading Saussure. London: Duckworth.

- Holdcroft, D. (1991). Saussure: Signs, System, and Arbitrariness. Cambridge University Press.

- Веселинов, Д. (2008). Българските студенти на Фердинанд дьо Сосюр (The bulgarian students of Ferdinand de Saussure). Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски" (Sofia University Press).

- Joseph, J. E. (2012). Saussure. Oxford University Press.

- Sanders, Carol (2004). The Cambridge Companion to Saussure. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80486-8.

- Wittmann, Henri (1974). "New tools for the study of Saussure's contribution to linguistic thought." Historiographia Linguistica 1.255-64.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ferdinand de Saussure |

| French Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Publications by and about Ferdinand de Saussure in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Works by or about Ferdinand de Saussure in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- The poet who could smell vowels: an article in The Times Literary Supplement by John E. Joseph, November 14, 2007.

- Original texts and resources, published by Texto, ISSN 1773-0120 (French).

- Hearing Heidegger and Saussure by Elmer G. Wiens.