Feminist pedagogy

Feminist pedagogy is a pedagogical framework grounded in feminist theory. It embraces a set of epistemological assumptions, teaching strategies, approaches to content, classroom practices, and teacher-student relationships.[1] Feminist pedagogy, along with other critical and progressive pedagogies considers knowledge to be socially constructed. Knowledge, understood to be non-objective and non-universal, is shaped by the possession of specific identities and the subjective experiences and perceptions that are a product of that identity (Johnson-Bailey and Ming-Yeh). Classrooms that employ feminist pedagogy use the various and diverse experiences located within the space as opportunities to cultivate learning. Using “experiences as basis for learning, demystifies canonical knowledge and exposes the role of gender, race and class in configuring power relations” (McClure). Feminist pedagogy addresses the power imbalances present in many westernized educational institutions and works toward de-centering that power. Within most traditional educational settings, the dominant power structure situates instructors as superior to students. Feminist pedagogy rejects this normative classroom dynamic, seeking to foster more democratic spaces functioning with the understanding that both teachers and students are subjects, not objects (McClure). Students are encouraged to reject normativity positions of passivity to enter into the role of active knowers and facilitators of learning. Within feminist pedagogy “self-knowledge on the part of the student that is not typically encouraged in the traditional academic” setting is confirmed and validated (Sandell). Central to Feminist Pedagogy is the understanding of a “symbiotic system of knowledge; a relationship between teacher and student in which both parties simultaneously learn from one another rather than a hierarchical passing of knowledge from teacher to student”. Under feminist pedagogy students are encouraged to develop critical thinking and analysis skills to deconstruct and challenge the “oppressive characteristics of a society that has traditionally served the politically conservative and economic privileged” (Johnson-Bailey and Ming-Yeh).

The theoretical foundation of feminist pedagogy is grounded in critical theories of learning and teaching such as Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Feminist pedagogy is an engaged process facilitated by concrete classroom goals in which members learn to respect each other's differences, accomplish mutual goals, and help each other reach individual goals. This process facilitates participatory learning, validation of personal experience, encouragement of social understanding and activism, and the development of critical thinking and open-minds.[4]It identifies the practical applications of feminist theory, while promoting the importance of social change, specifically within the institutional hierarchy found in academia. Feminist Pedagogy is employed most frequently in Women’s Studies classes, which aim to transform [students] from objects to subjects of inquiry.[3] However, the use of feminist pedagogy is not restricted only to Women's Studies courses.

Atmosphere of the academy

“The academy not only defines what knowledge is, but also defines and regulates what a student is. It differentiates and limits who can be a learner and what or how” they “can learn and this prescribes our potential and status in society” ). Feminist pedagogy arises from the rejection of traditional institutional structures and practices. Western academies, specifically within the U.S. and Canada, “reflect the current intensification of neoliberalism”, a trend that has resulted “in the increased corporatization of education” (Magnet et al.). “In the academy, liberal conceptions of the rational individual still reign supreme, and educational and research pursuits are based on neoliberal economic prescriptions of free-market competition for limited funding and comparative advantages in original and individual theories” (Magnet et al.). “Education is another institution in which oppressive social structures are reproduced through the generation and dissemination of Eurocentric knowledge (Johnson-Bailey and Ming-Yeh)”. The institution of education operates within the larger hierarchical power structure based on gender, race, class, and disability that erases and silences marginalized voices (Magnet et al.). Institutionalized education also promotes the “banking system” approach to education which views students as empty vessels, waiting to be filled the specific knowledge provided by the teacher and the institution at large (Magnet et al.).

The educational climate of the academy, the result of dominant neoliberal competitive ideologies downplays and discourages “communal process of learning, research, and community action” (Magnet et al.). Classroom power dynamics operating within neoliberal institutions, “exhibit a competitive style of engagement” that employs fear and shame as a motivators for student growth (Magnet et al.). Traditional approaches to education maintain the status quo, reinforcing current power structures of domination. The “academic work process is essentially antagonistic to the working class, and academics for the most part live in a different world of culture, different ways that make it, too, antagonistic to working class life” (hooks). In contrast Feminist Pedagogy rejects societal systems of oppression, recognizing and critiquing institutional and individual compliancy associated with the academy that perpetuate larger ongoing societal oppressions. The classroom is a microcosm of how power is disturbed and exercised in the larger society. “Students use subtle means to keep their vested power and attempt to enforce and replicate the status quo in the classroom” (Johnson-Bailey and Ming-Yeh).

Qualities of feminist pedagogy

“Critical pedagogy posits that knowledge is not static and unitary but rather results from an open ended process of negotiation and interaction between teacher and student. Feminist pedagogy, as an offshoot of critical pedagogy, further holds that gender plays a critical role in the classroom, influencing not only what is taught, but how it is taught.” (McClure). Like all forms of critical pedagogy feminist pedagogy aims "to help students develop consciousness of freedom, recognize authoritarian tendencies, and connect knowledge to power and the ability to take constructive action."[8] Feminist pedagogy aligns itself with many forms of critical pedagogy including those focused on race and ethnicity, class, postcolonialism and globalization.

The introduction of the book Feminist Pedagogy: Looking Back to Move Forward by Robbin D. Crabtree explains the qualities, and distinctions from critical pedagogy, thus: "Like Freire’s liberatory pedagogy, feminist pedagogy is based on assumptions about power and consciousness-raising, acknowledges the existence of oppression as well as the possibility of ending it, and foregrounds the desire for and primary goal of social transformation. However feminist theorizing offers important complexities such as questioning the notion of a coherent social subject or essential identity, articulating the multifaceted and shifting nature of identities and oppressions, viewing the history and value of feminist consciousness-raising as distinct from Freirean methods, and focusing as much on the interrogation of the teacher’s consciousness and social location as the student’s."[9]

Feminist pedagogy concerns itself with the examination of societal oppressions, working to dismantle the replication of them within the institutional settings. Feminist educators work to replace old paradigms of education with a new one which focuses on the individual's experience alongside acknowledgment of one's environment.[6] It addresses the need for social change and focuses on educating those who are marginalized through strategies for empowering the self, building community, and ultimately developing leadership.[7] Feminist pedagogy, operating within a feminist framework, embodies a “theory about the transference of knowledge that shapes classroom practices by “providing criteria to evaluate specific educational strategies and techniques in terms of the desired course goals or outcomes (Shrewsbury 1993). A number of distinctive qualities characterizes feminist pedagogies and the instructional techniques that arise out of feminist approaches. Of the associated qualities, some of the most prominent features include development of reflexivity, critical thinking, personal and collective empowerment, the redistribution of power within the classroom setting, and active engagement in the processes of re -imaging. (Shrewsbury 1993). The critical skills fostered with the employment of a feminist pedagogical framework encourages recognition and active resistance to societal oppressions and exploitations. In addition feminist pedagogies position it’s epistemological inquiries within the context of social activism and societal transformation.

Reflectivity, essential to the execution of feminist pedagogy, allows for students to critically examine the positions they occupy within society. Positions of privilege and marginalization are decoded, producing a theorization and greater understanding of one’s multifaceted identity and the forces associated with the possession of a particular identity (Shrewsbury 1993). Critical thinking is another quality of feminist pedagogy that is deeply interconnected with practices of reflectivity. The critical thinking encouraged by feminist pedagogy is firmly rooted in everyday lived experiences (Shrewsbury 1993). Critical thinking is employed inside and outside of the classroom space to challenge dominant cultural narratives and structures.

Empowerment within the classroom setting is central to Feminist pedagogical instructional techniques. Students are confirmed in their identities and experiences and are encouraged to share with the space personal understandings to build a diverse and intersectional base of knowledge. Classroom spaces that operate from within a feminist pedagogical framework value integrity of the participants and the collective respect of existing differences in experiences and knowledge (Fisher). Validation of student realities fosters the development of individual talents and ability and solidification of group cohesion. Empowerment of the student body is achievable through the intentional dissemination of traditional classroom power relations. It is understood and central to the success and progression of the classroom space that power is shared throughout all its constituents. In traditional academic settings the position of power is maintained through the authority exercised by the instructor. The structure of this power relation solely validates the teacher’s experiences and knowledge, maintaining that students have little to offer in the facilitation of learning (Fisher). At its core, feminist pedagogy aims to decenter power in the classroom to give students the opportunity to voice their perspectives, realities, knowledge, and needs.[21] This can be utilized through the process of decentering power, where the educator distances themselves from their authority status and enables their students to have equal footing with them. Unlike many other methods of teaching, feminist pedagogy challenges lectures, memorization, and tests as methods for developing and transferring knowledge.[21] Feminist pedagogy maintains that power in the classroom should be delicately balanced between teacher and students in order to inform curriculum and classroom practices. The sharing of power creates a space for dialogue that reflects the multiple voices and realities of the students. By sharing the power and promoting voice among students, the educator and students move to a more a democratic and respectful relationship that recognizes the production of knowledge by both parties. The shared power also decentralizes dominant traditional understandings of learning by allowing students to engage with the professor freely, instead of having the professor simply give students information (Fisher).

Feminist Pedagogical theorists not only question the current climate of the classroom but engage in speculations of what it could exist as (Shrewsbury 1993). Understandings facilitated within the classroom space is not meant to exist within the confines of academia but are encouraged to facilitate social activism (Hoffman and Stake). Theory and classroom explorations are positioned in relation to their social contexts and implications. Students are encouraged to take what they learn in the classroom and apply their understandings to institute social change.

History

Feminist Pedagogy evolved in conjunction with the growth of women’s studies within the academic institution. The increased awareness of sexism occurring on college campuses and the need to promote professionalism within certain segments of the women’s movement resulted in the institutionalization of women's studies programs (Weiler). Women studies programs “reexamined and expanded traditional disciplines from a woman's perspective” (Sandell). The institutionalization of women’s studies programs, facilitated the challenging of existing canons and disciplines which is reflected in classroom teaching methods (Weiler). “The field of Women's Studies has expanded dramatically since the first courses were offered in 1970. The critiques of dominant paradigms and compensatory research efforts that characterized its early stages generated an explosion of scholarship that has significantly expanded the undergraduate women's studies curriculum, made possible the development of graduate level instruction, and propelled efforts to integrate the evolving scholarship on women across the curriculum. Throughout the evolution of the field, the processes of teaching women's studies courses have received considerable scholarly attention, resulting in a significant body of theory that attempts to define elements of feminist teaching” (Weiler).

Influential figures

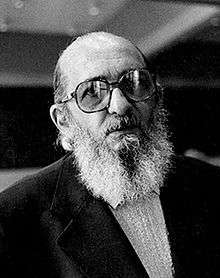

Paulo Freire

The theorist Paulo Freire is known for his works in the area of critical pedagogy. “Freire’s theories have profoundly influenced literacy programs throughout the world and what has come to be called critical pedagogy in the United States. His theoretical works, particularly Pedagogy of the Oppressed (written in 1968) , provide classic statements of liberatory or critical pedagogy based on universal claims of truth” (Weiler). Freire is also known for his disdain of what he called the "banking" concept of education, in which a student is viewed as an empty account waiting to be filled by the teacher. He said that "it transforms students into receiving objects. It attempts to control thinking and action, leads men and women to adjust to the world, and inhibits their creative power" (Freire, 1970, p. 77)[14]

“Freire’s work emphasized the need for teachers to eschew their class perspective and see both education and revolution as process of shared understanding between the teacher and the taught, the leader and the led” (Fisher).“Feminist pedagogy as it has developed in the United States provides a historically situated example of a critical pedagogy in practice. Feminist conceptions of education are similar to Freire's pedagogy in a variety of ways, and feminist educators often cite Freire as the educational theorist who comes closest to the approach and goals of feminist pedagogy. Both feminist pedagogy as it is usually defined and Freirean pedagogy rest upon visions of social transformation; underlying both are certain common assumptions concerning oppression, consciousness, and historical change. Both pedagogies assert the existence of oppression in people's material conditions of existence and as a part of consciousness; both rest on a view of consciousness as more than a sum of dominating discourses, but as containing within it a critical capacity — what Antonio Gramsci called "good sense"; and both thus see human beings as subjects and actors in history and hold a strong commitment to justice and a vision of a better world and of the potential for liberation” (Weiler).

bell hooks

Gloria Jean Watkins, better known by her pen name bell hooks, is an accomplished writer and educator.

In Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, she argues that a teacher's' use of control and power over students dulls the students' enthusiasm and teaches obedience to authority, "confining] each pupil to a rote, assembly-line approach to learning.”[15] She advocated that universities encourage students and teachers to collaborate, making learning more relaxing while simultaneously exciting. She describes teaching as “a catalyst that calls everyone to become more and more engaged”

Hooks advocates what she calls engaged, interactive, transgressive pedagogies. Hook’s pedagogical practices exist as “interplay of anticolonial, critical, and feminist pedagogies” (Magnet et al.). hooks based pedagogy on freedom, "Creating community in the classroom resembles both democratic process and a healthy family life, as shaped by 'mutual willingness to listen, to argue, to disagree, and to make peace." [16]

hooks also builds a bridge between critical thinking and real-life situations to enable educators to show students the everyday world instead of the stereotypical perspective of the world. Hooks argues that teachers and students should engage in interrogations of cultural assumptions that are supported by oppression (Magnet et al.).

Patti Lather

Patti Lather has taught qualitative research, feminist methodology, and gender and education at Ohio State University since 1988. She is the author of Getting Smart: Feminist Research and Pedagogy With/in the Postmodern and Getting Lost: Feminist Efforts Toward a Double(d) Science.[1]

Ileana Jiménez

Ileana Jiménez is a high school teacher in New York City who teaches courses on feminism, LGBT literature, Toni Morrison, and memoir writing.[2] She is nationally known for her writing and speaking about inclusivity in high schools, her work to make schools safer spaces for LGBT students, and has won numerous awards for curriculum development.[2] She was heavily influenced in her feminism and her pedagogy by bell hooks.[3] Ileana Jiménez teaches a class at Elisabeth Irwin High School in New York called “Fierce and Fabulous: Feminist Writers, Artists and Activists”. This class consists of juniors and seniors. The objective of this class is to bring feminism to the attention of teens. Educate through an intersectional lens to help students comprehend their lives. Jiménez wants to apply the feminist pedagogy to engage her students with the national and global issues of or every day lives. “Intersections, which explains how intersectionality helps understand power and oppression, identify and agency.” [4]

Practical implementation

At its core, feminist pedagogy aims to decenter power in the classroom to give students the opportunity to voice their perspectives, realities, knowledge, and needs.[5] This can be utilized through the process of decentering power, where the educator distances themselves from their authority status and enables their students to have equal footing with them. Pedagogy can also be implemented practically through the use of engaging in activism, within the classroom and outside of it.

Decentering power

One of the main tenets of feminist pedagogy is transforming the teacher and student relationship. Under this teaching method, educators seek to empower students by offering opportunities for critical thinking, self-analysis, and development of voice. Unlike many other methods of teaching, feminist pedagogy challenges lectures, memorization, and tests as methods for developing and transferring knowledge.[5] Feminist pedagogy maintains that power in the classroom should be delicately balanced between teacher and students in order to inform curriculum and classroom practices. The sharing of power creates a space for dialogue that reflects the multiple voices and realities of the students.

By sharing the power, to promote voice among students, the educator and students move to a more equal position in which students produce knowledge. The shared power also decentralizes dominant traditional understandings of learning by allowing students to engage with the professor freely, instead of having the professor simply give students information.

Consciousness raising

One of the main methods that feminist teachers utilize this decentering of power is through the process known as “consciousness raising”. Popularized in the early 1970s, the method is implemented usually by sitting in a circle and discussing one’s own experiences and by finding commonalities that individuals thought were only personal matters of their own lives. Ideally, consciousness raising is used as a method to increase the number of people who are aware of a social issue or problem.[6]

Activist projects

Activist projects encourage students to identify real-life forms of oppression and to recognize the potential of feminist discourse outside of the academic realm. The goals of this practical application of feminist pedagogy include raising students’ consciousness about patriarchal oppression, empowering them to take action, and helping them learn specific political strategies for activism.[7] Students’ activist projects have taken a variety of forms, including organizing letter-writing campaigns or writing letters to the editor, confronting campus administration or local law enforcement agencies, organizing groups to picket events, and participating in national marches.[8]

Feminist teachers who have written about their experiences assigning activist projects recognize that this non-traditional method can be difficult for students. One noted difficulties along the way, including students who resisted putting themselves in a controversial position,[9] and students who had trouble dealing with backlash.[10] Since they want students to have a positive, yet challenging (often first) experience with activism, they often give students a great deal of freedom in choosing a project. Teachers may students to develop a project that would “protest sexism, racism, homophobia, or any other ‘ism’ related to feminist thought in one situation”.[11]

Feminist assessment

Literature on feminist assessment is sparse, possibly because of the incongruity between notions of feminism and assessment. For example, traditional assessments such as standardized tests validate the banking model of learning and the concept of assessment in the form of grades or ability to advance within a structured curriculum is a form of power held by an institution. Nonetheless, literature on feminist pedagogy does contain a few examples of feminist assessment techniques.[12][13][14] These techniques decenter the power structure upheld by traditional assessment by focusing on student voice and experience, which allows students agency as they participate in the assessment process.[15]

The use of journaling is considered to be one feminist assessment technique [15] as well as the idea of “participatory evaluation”, or evaluations characterized by interactivity and trust.[16] Assessment techniques borrowed from critical pedagogy should be considered when thinking of feminist assessment approaches.[17] These may include involving students in the creation of assessment criteria or peer assessment or self-assessment.[18] Finally, Accardi argues feminist assessment approaches can be embedded into more traditional forms of assessment (such as classroom assessment techniques or performance assessment techniques) if students are allowed to reflect on or evaluate their experiences. Surveys, interviewing and focus groups, too, could be considered assessments with a feminist approach provided that a student voice or knowledge is sought.[19] These assessment strategies should be tailored to the type of instruction taking place; performance assessment techniques may be more appropriate for short term instruction. If the instructor has more time with the learner, then the opportunity for more in-depth, reflective feedback and assessment is possible.

Critiques

There are several elements of Feminist Pedagogy that has been criticized over the years. The distinctiveness of Feminist Pedagogy from other critical and progressive pedagogies have been brought into question (Hoffman and Stake):

“Feminist pedagogy shares intellectual and political roots with the movements comprising the liberator education agenda of the past 30 years.These movements have challenged traditional conceptions of the nature and role of education, and of relationships among teachers, learners, and knowledge. They have promoted efforts to democratize the classroom, to clarify and expose power relationships within and outside the classroom, and to encourage student agency, both personal and political. Moreover, they have called for education to be relevant to social concerns, arguing that knowledge generated and transmitted in the classroom should relate to the lives of those it describes and facilitate social justice in the world at large (Hoffman and Stake).

Exploring the similarities between feminist and other critical and progressive pedagogies, the argument that feminist pedagogy is not entirely distinct from other pedagogies in its ideologies and strategies contains some validity (Hoffman and Stake).

Feminist Pedagogy aims to redistribute power throughout the classroom. Despite attempts to restructure power relations there remains the possibility of maintaining traditional educational hierarchy in feminist classrooms. “Even those professors who embrace the tenets of critical pedagogy (many of women are white and male) still conduct their classrooms in a manner that only reinforced bourgeois models of decorum” (hooks). The intentionality behind efforts to redistribute power have the possibility of simply masking power relations rather than authenticity exposing and addressing the compositional makeup of power. Regardless of efforts to create more egalitarian teacher/student interactions, teachers still largely determine the direction of the classroom, it is teachers who “set the agenda and assign grades, not the students (McClure). Feminist Pedagogy, focusing acutely on the power relations between student and teacher can often fail to address the power dynamics that operate among class participants. “As the classroom becomes more diverse, teachers are faced with the way the politics of domination are often reproduced in the educational setting. For example, white male students continue to be the most vocal in our classes. Students of color and some white women express fear that they will be judged as intellectually inadequate by these peers (hooks).

Hegemonic white feminism has been criticized for being oppressive in its failure to address and incorporate intersectionality within its ideological consciousness. “Many have charged American feminism with claims of racism class elitism from within its mostly academic boundaries”, charging that American feminism “has become “another sphere of academic elitism”” (Magnet et al). “It is important to note that many white female (and male) scholars, even self identified feminists, do not value every one's presence in the collective effort of women's or human liberation, hooks refers to these folks as co-oppressors in society, alongside others from privileged classes who do not participate in struggles against oppression in our complex society” (Magnet et al.). Women’s studies programs in United States “have not adequately addressed white supremacy and capitalism, and thus in fact bolstered Eurocentrism and racism in the academy (Magnet et al).

Bernice Fisher points out the ways in which feminist pedagogy is at odds with it’s historical roots in the tradition of “consciousness raising”. “Consciousness raising” groups were an important part of the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s. “Consciousness raising” is the method of discussing and sharing one’s own experiences with others which fosters the discovery of finding commonalities between individuals. Through “consciousness raising” groups, individuals were able to recognize that they shared similar struggles, thus the number of people aware of a particular social issue increased. “Most discussion of feminist pedagogy can be seen as a struggle to reconcile the cr vision with the realities of higher education. Since the latter assumes and generally supports competition and an individualistic orientation toward learning, one of the first problems for the feminist teacher is to create the kind of trust which cr presupposes” (Fisher). With the institutionalization of women’s studies within the academic, feminist teacher were dispersed into “less radical universities, community colleges and other contexts where the rhetoric of feminism was far less familiar and more threatening, the situation tended to be reversed, teachers who were activists were in touch with, or part of, the changing women’s movement, and in a sense became its representatives to the students (Fisher).

References

- ↑ http://people.ehe.osu.edu/plather/

- 1 2 Jiménez, Ileana. "About Ileana Jiménez". Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Jiménez, Ileana (September 7, 2010). "Teaching to Transgress in High Schools". Ms. magazine blog. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Jiménez, I. (2013, Winter). Feminist high. Ms, 23, 48-49. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1312702814

- 1 2 Bryson; Bennet-Anyikwa (2003). "The Teaching and Learning Experience: Deconstructing and Creating Space Using a Feminist Pedagogy." Race Gender and Class.".

- ↑ Hanisch, Carol. "Women's Liberal Consciousness-Raising: Then and Now". On the Issues Magazine. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Rose 1989, p. 489.

- ↑ Rose, Suzanna (1989). "The Protest as a Teaching Technique for Promoting Feminist Activism". NWSA Journal. 1 (3): 487–488.

- ↑ Rose 1989, p. 488.

- ↑ Rose 1989, p. 490.

- ↑ Rose 1989, p. 487.

- ↑ Hutchings, P. (1992). The assessment movement and feminism: Connection or collision? In Musil, C. T. (Ed). Students at the center: Feminist assessment (pp. 17-38). Washington D.C.: Association of American Colleges.

- ↑ Shapiro, J.P. (1992). What is feminist assessment? In Musil, C. T. (Ed). Students at the center: Feminist assessment (pp. 29-37). Washington D.C.: Association of American Colleges.

- ↑ Accardi, M. (2013). Feminist pedagogy for library instruction. Sacramento: Library Juice Academy.

- 1 2 Accardi, M. (2013). Feminist pedagogy for library instruction. Sacramento: Library Juice Academy. (p. 77-78)

- ↑ Shapiro, J. (1988). Participatory Evaluation: Towards a Transformation of Assessment for Women's Studies Programs and Projects. Educational Evaluation & Policy Analysis, 10(3), 191-199.

- ↑ Accardi, M. (2013). Feminist pedagogy for library instruction. Sacramento: Library Juice Academy. (p. 79)

- ↑ Price, M., O’Donovan, B., & Rust, C. (2007). Putting a social constructivist assessment process model into practice: building the feedback loop into the assessment process through peer review. Innovations in Education & Teaching International, 44(2), 143-152).

- ↑ Accardi, M. (2013). Feminist pedagogy for library instruction. Sacramento: Library Juice Academy. (p. 83-7)