Felling, Tyne and Wear

| Felling | |

View into Central Felling |

|

Felling |

|

| Population | 8,908 |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | NZ279618 |

| Metropolitan borough | Gateshead |

| Metropolitan county | Tyne and Wear |

| Region | North East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | GATESHEAD |

| Postcode district | NE10 |

| Dialling code | 0191 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Tyne and Wear |

| Ambulance | North East |

| EU Parliament | North East England |

| UK Parliament | Gateshead |

|

|

Coordinates: 54°57′00″N 1°33′50″W / 54.950°N 1.564°W

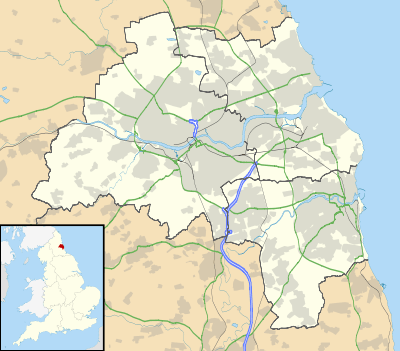

Felling is one of the largest urban areas in Gateshead, Tyne and Wear, England. Formed when three villages coalesced in the 19th century, the town of Felling was subsumed by neighbouring Gateshead in 1974 and it now forms part of the metropolitan borough of Gateshead. It lies on the B1426 Sunderland Road and the A184 Felling bypass, less than 1 mile (1.6 km) east of Gateshead town centre, 1 mile (1.6 km) south east of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and 10 miles north west of the City of Sunderland. In 2011, Felling had a population of 8,908.

The history of Felling stretches almost eight hundred years. The original manor at Felling was granted in the 13th century and passed through several families until it was passed to the Brandling family in 1509. While Lords of the Manor, several members of this family served as Members of Parliament among other civic duties. They were also instrumental in bringing heavy industry to the area, and Felling Colliery (John Pit), one of the oldest and largest collieries in the region, was developed on their estate. The colliery was the site of two mining disasters which cost over one hundred lives, to which Sir Humphrey Davey and George Stephenson developed their safety lamps (There is a monument to the workers lost in St Mary's churchyard, Heworth). Other heavy industry took root in the 18th and 19th centuries so that Felling developed from a rural scattering of villages into firstly three distinct settlements at Low and High Felling and Felling Shore, then in 1894 these amalgamated with other local villages into the town of Felling, administered by the Felling Urban District Council at Sunderland Road. The areas that Felling council were responsible for were Felling, High Felling, Windy nook, Leam lane estate, Pelaw,Wardley,Heworth, Bill quay and Follingsby. The council was disbanded in 1974 when Felling was wholly incorporated into the new Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead.

Felling today is broadly residential save some light industry located at the bank of the River Tyne in north Felling. It is governed locally and nationally by the Labour Party. The vast majority of residents identify as white British and, in the north areas particularly, there are high levels of unemployment and deprivation. It is well served by public transport; there are several bus services through the area and Felling lies on the Tyne and Wear Metro line and there are stations at Gateshead Stadium and Felling. Felling town centre remains the principal economic area and has recently benefitted from a £13.5 million regeneration project, with the demolition of the old Co-op supermarket and council building and rebuilding of the town shopping centre shopping units, which now run parallel to a new Asda superstore.The long and rich history of the area is reflected by over a dozen listed buildings, several churches and numerous public houses which are locally listed. It is served by several schools, though levels of educational qualification among residents are comparably low. Leisure provision is good, with four distinctive parks and various riverside facilities. Gateshead International Stadium lies in the area and several professional footballers hail from Felling, including former England international Chris Waddle, as does award-winning author David Almond.

History

Early history

The name of Felling is recorded as early as 1217 and, in 1920, was said to refer to a clearing where woods and trees were felled.[1] Since there are no other places in Britain which bear this name, despite country-wide tree felling, it is much more likely to be because it lies on the eastern descent of a Fell, which rises from Team Valley in the west to Low Fell, then still rising to High Fell, before descending down to the Tyne through Felling. Ing is a place name ending which means "the people of". In the 13th century, the Prior of Durham enfeoffed Sir Walter de Selby a manor at Felling "to hold by homage, fealty, knights' service, two marks rent, and suit at the prior's every fortnight".[2] The estate then passed to Walter's son, Adam, whose own son forfeited the estate the manor upon his death, whereupon it was passed to Ralph de Applingden.[3] In 1331, the manor was granted to Sir Thomas Surtees by Bishop Lewis Beaumont, who passed it to his son Alexander and whose own son, Thomas, inherited the estate in 1400 when he was only 20 weeks old. Thomas lived only 35 years, but is notable for having been High Sheriff of Northumberland in 1422.[4] The estate continued to pass through the Surtees family until 1509, when the last surviving member of that family died.[2]

There followed a period of extensive litigation as the future of the considerable Surtees estate, which also included Low Dinsdale Manor near Darlington, was contested between the families Brandling, a staunchly Royalist and Catholic family, Blaxton and Wyclyffe.[5][6] While several elements of the estate where divided by share, in 1509 the entire manor of Felling was granted by Deed of Partition to Robert Brandling and his heirs "for life and to the total extinction" of any other claims.[7]

The Brandling family

Brandling duly lived at Felling with his wife Anne. He became sheriff of Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1524, was mayor of Newcastle five times and was knighted by the Duke of Somerset at Mussleburgh. When he died in 1568, the estate passed to his brother Thomas.[8] In 1605, Thomas' grandson, Robert Brandling, inherited the manor. Robert Brandling was granted Newminster Abbey by King James in 1810, served as High Sheriff of Northumberland in 1617 and was in 1621 elected Member of Parliament for Morpeth.[9] When he died in 1636, the estate passed to his son, Sir Francis Brandling. Francis was also an MP, albeit for Northumberland, between 1824–25 though he abandoned Felling in favour of residence at Alnwick Abbey.[7][10] He died in 1641 and was succeeded by Charles Brandling, a cavalry colonel who also resided at both Felling and Alnwick. Charles had two brothers. The older of which, Ralph, was killed at the Battle of Marston Moor,[11] while the second brother, Robert, also participated in the English Civil War and was captured in an otherwise successful Royalist engagement at Corbridge in February 1644 after which he switched sides and fought for the Roundheads; an action which earned his the reputation as "a very knave" which he carried until his death in 1669.[5]

Early industrialisation 1680–1800

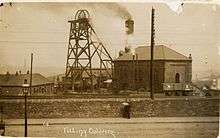

By the turn of the 18th century, Felling consisted of little more than the large Brandling estate and a small scattering of tiny farming villages.[12] However, Ralph Brandling, the incumbent of the Brandling estate at that time, had come to realise the value of the rich coal deposits on his estate and began drift mining around 1670.[12][13] He initially found the large coal seams under his estate difficult to extract due to their depth, and indeed it was imported coal from Newcastle-upon-Tyne which saw the development of more extensive industries in salt, glass and chemicals which began to attract workers to the area.[12] At around 1750, a large copper-works was opened at the banks of the River Tyne; the first such works to be developed on the river.[14][15] Encouraged by these developments, Ralph Brandling's son, Charles Brandling,[note 1] firstly commissioned more extensive mining of near-surface coal on his estate and then, encouraged by the discovery of several strata below his estate, began boring operations in 1758 to allow ultimately for deeper coal extraction.[16][17] The result was the opening of Felling Colliery[note 2] in 1779, working on the High Main stratum at a depth of 125 fathoms.[2][16] A brown paper mill was also opened in 1798.[14]

Felling mining disasters

On 19 January 1811, the original High Main seam at Felling Colliery was closed, but by that time the colliery had grown enormously.[18][note 3] The colliery was deepened to reach the Low Main seam. Two shafts were provided: John Pit and William Pit.[19] The Low Main and began operation in October 1810.[2] Disaster struck Felling Colliery on 25 May 1812 when, despite the colliery containing the most up-to-date safety measures,[20] firedamp ignited and at around 11.30 am, "one of the most tremendous explosions in the history of coal mining took place".[2] Two explosions rocked the colliery, the blast appearing in both pits.[19] A cloud of coal dust and debris over a radius of a mile and a half was ejected from the colliery.[21] One account recalled:

Immense quantities of dust and coal rose high into the air in an inverted cone...In the village of Heworth, this cloud caused a darkness like that of early twilight and covered the roads so thickly that the footsteps of passengers were deeply imprinted in it. As soon as the explosion was heard, wives and children of the workmen ran to the pit. Wildness and terror were pictured in every countenance. The crowd soon collected to several hundreds, some crying out for a husband, others for a parent or a son, and all affected by a mixture of horror, anxiety and grief.[22]

Following the first blast at 11:30, rescue attempts started at 12:15. At 14:00 the second blast occurred and no further rescues occurred.[19] Some 29 men were saved, but the remaining 92 men and boys were killed.[2] Two days later the decision was made to seal the colliery to starve the fire of oxygen.[19] Just one year later, on 24 December 1813, a further catastrophe occurred:

About half-past one o'clock on the morning, an explosion took place in Felling colliery, by which nine men and thirteen boys were hurried into eternity, several others severely burnt, and all the underground horses but one destroyed. The accident occurred at the time of calling course, or when one set of men were relieving another. Several of the morning shift men were standing round the mouth of the pit, waiting to go down, when the blast occurred, and the part who had just descended met it soon after they had reached the bottom of the shaft; these were most miserably burnt and mangled.[23]

The 200th anniversary of the first disaster was commemorated in Felling on 25 May 2012 by a parade from St Mary's Church at Heworth to the place of the entrance to the colliery at Mulberry Street.[24]

The Industrial Revolution

In spite of the disaster, Felling continued to grow and by the time of the explosions the character of Felling had changed substantially. There now existed three distinct villages. Around two miles south east of Gateshead lay High Felling; a residential village in the township of Heworth which had attracted several Wesleyan and Methodist preachers.[25] Slightly to the north lay Low Felling. This was a more heavily industrialised village, containing Felling colliery, a large chemical works and other manufacturers,[25] though in 1834 it was noted that there also existed "a few neat houses and many cottages for the colliery which, with small gardens attached, give an aspect of comfort to the village".[26] At the north and on the bank of the River Tyne, a populous manufacturing and trading village had developed known as Felling Shore, spreading across three miles of the bank of the Tyne. A Methodist church was built there in 1805. This was accompanied by several shops and four public houses frequented predominantly by seamen and workers at the adjacent quay, coal staithes and ship building works where vessels of excellent quality were built.[15][25] Industry continued to flourish here; the copperworks established in the 18th century still operated and had expanded, an oil and a paper mill had also developed, along with forging works for anchors and shovels.[14]

In 1827 the Friars Goose Chemical Works was opened by Anthony Clapham. In 1834 a second large chemical works was established by Hugh Lee Pattinson, John Lee and George Burnett;[27] it soon employed around 300 men.[14][28] Grindstone quarries produced high quality stone and a brownware pottery under Mr. Joseph Wood had opened for business.[15] In 1842, Brandling Station was opened at Mullbery Street in Felling on the Brandling Junction railway linking Gateshead, South Shields and Sunderland.[29] This is one of the oldest passenger stations in the world.[30]

By around 1870, Felling had reached its industrial peak. Historian John Marius Wilson noted:

FELLING, a large village and a chapelry in Jarrow parish, Durham. The village stands on the Northeastern railway, 1½ mile SE of Gateshead; increased recently from two hamlets to its present condition; is maintained by factories and by mining operations; connects with Felling-Shore, a coal-shipping place on the Tyne; and has a post-office under Gateshead, a r. station, a church built in 1866, four dissenting chapels, and a Roman Catholic chapel. The chapelry was constituted in 1866. Population 5,105. The living is a vicarage. Value, £300. Patrons, Five Trustees.[31]

1870 – present day

The industrial heights proved reasonably short-lived. By 1860, improvements to access along the River Tyne only served to highlight the better sites on the Tyne bank and so shipbuilding at Felling Shore began to decline. This decline was hastened by the limited space at Felling dock, which could not reasonably be extended and so progress enjoyed elsewhere was never matched at Felling.[32] At around the same time, the chemical industry began to stall as bigger and more efficient competitors overtook their Felling counterparts.[32] The industrial decline was matched by continuous residential growth, so that by the Victorian era those industrial elements which survived were met by a large sprawl of housing from the south where High and Low Felling had effectively merged.[33]

At 10:52 am on 26 March 1907, an express passenger train travelling from Heworth signal box derailed on the approach to Felling station.[34] The cause was a combination of a sharp frost in the morning and unseasonal heat later in the day which saw the track expand and kink.[35] The derailment, which saw all bar two carriages rolled over entirely, cost two passengers their lives, with eight more seriously hurt and a further 34 suffering minor injuries such as shock.[34]

The decline of heavy industry, meanwhile, continued apace. In 1932 the large chemical works at Felling Shore closed and was left derelict, leaving behind a 2 million tonne heap of spoil.[28] Felling Colliery, the oldest and most extensive of all Felling's industry, had changed hands numerous times after the Brandlings finally sold their stake in the 1850s and ultimately closed in 1931 with the loss of 581 jobs.[17] Fairs boat yard at Felling Shore had been sold in 1919 and became Mitchison's ship yard, but this too closed in 1964.[28]

In place of industry came housing. The high density terraced housing which had accompanied the industrial boom of the 19th century had sprawled south and was soon joined by a wave of development at the run of the 20th century.[36] The earlier housing came at Stuart Street, Temple Street and Helmsdale Avenue in the form of Tyneside flats.[37] In the inter-war years, whole derelict industrial areas were cleared and large council estates of semi-detached houses, with front and back gardens, were built at the Old Fold, Stoneygate, Brandling and Nest estates.[36][38] By the time that Felling ceased to be an independent town and was incorporated into the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead in 1974, Felling had become a "dormitory area" and remains so today.[39]

Economy

There are two principal economic areas in Felling. The first of these is at Felling Shore, where the East Gateshead Riverside Park was built in 1966 and which, combined with the Felling Shore industrial estate, today houses 241 businesses employing around 6,400 people.[28] The second is in central Felling in the town centre area around Victoria Square. The town centre has seen massive investment over recent years, with the complete redevelopment of the main shopping centre and addition of a new Asda superstore, a Greggs bakery, Card Factory shop, Subway sandwich outlet and a local taxi business. Other amenities include a Post Office, Heron Foods store and several bookmakers, as well as 4 public houses and fast food outlets [40][41]

The Felling Health Care Centre is the main source of General Healthcare for the town's population, and houses St Alban's medical group and Crowhall Medical Group. The GP surgery also has a small Boots pharmacy in addition to the larger Boots store in the town centre.

Felling has one small dentist practice located on the B1426 main commuter road that connects Heworth to Gateshead town centre

Levels of unemployment in Felling are high. Only 52.4% of the total working age population are in employment, as compared to 61.7% in the borough overall. Around 10% of residents claim Jobseeker's Allowance; this is double the Gateshead average and is the highest figure in the borough.[42] Youth unemployment levels are also very high at 14%, which compares to a borough average of 9% and is also the highest figure in Gateshead. The average income of residents is only £18,000 per annum; this compares to a Gateshead average of £27,000 and is the lowest figure in the borough.[43]

Geography and topography

Felling, at latitude 54.950° N and longitude 1.564° W, lies less than 1 mile (1.6 km) south and east of Gateshead town centre on a bed of carboniferous sandstone and clay, interspersed with coal measures laid down around 300 million years.[44] It is split bilaterally by the Felling By-Pass[45] to the north and by Sunderland Road more centrally.[46] The distance from Felling to London is 255 miles (410 km).

The urban expansion of Gateshead makes exact overall boundaries difficult to define. Although administratively considered one area, official documentation has split Felling into three distinct neighbourhoods: North, Central and High Felling.[47][48][49] Felling North is roughly comparable to the old settlement at Felling Shore, bounded to the north by the River Tyne and the south by Sunderland Road.[50] The other neighbourhoods also broadly follow their historical boundaries; the central area includes Felling town centre and the surrounding streets, while High Felling incorporates Coldwell Lane and the adjoining streets moving south towards Windy Nook.[51][52]

Felling lies on land which is steep at the riverbank but which initially flattens at the north then begins to climb,[53] with some slope south to north centrally[54] before consistently sloping, at times steeply, in High Felling. At the south-west corner, the land reaches a maximum height of around 130 metres (430 ft) above sea-level.[55]

Felling is now largely bordered by settlements which are part of the metropolitan borough. These are Windy Nook to the south, Deckham and the town of Gateshead to the west and Heworth and the Leam Lane Estate to the east. To the extreme north, Felling is bounded by the River Tyne, the largest river in the North East of England. This affords very good views into Newcastle upon Tyne.[56]

Land use is mixed. The land to the extreme north adjacent to the river is mostly industrial, split by the Felling By-Pass.[57] The land south of the By-Pass towards the town centre is predominantly residential and includes the Nest, Brandling, Stoneygate and the Old Fold estates.[58] Centrally the land is mixed between residential properties and the largely commercial use at Crowhall Lane and Victoria Square.[54][59] At High Felling, land use is predominantly residential but there is around 25% green-space, including a park, cricket ground and urban open space to the south at Albion Street.[55]

|

Gateshead | River Tyne | Pelaw |  |

| Deckham | |

Heworth | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Carr Hill | Windy Nook | Leam Lane Estate |

Governance

| Gateshead Council, Felling–2012 local elections[60] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate name | Political party | Number of votes | % of votes cast |

| Sonja Dickie | Labour | 1,365 | 85.8% |

| Trevor Charles Murray | Conservative | 136 | 7.8% |

| Ian Gill | Liberal Democrats | 113 | 6.5% |

In 1843, High Felling, Low Felling and Felling Shore were independent villages in the Chapelry of Heworth, along with High and Nether Heworth, Bill Quay, Windy Nook, Carr Hill, Wardley and Follingsby.[61] In 1894 the first Felling Urban District Council sat at Felling. The council "was the offspring of that ancient township and inherited its customs, its local government, its land and its people", so that all of those villages combined to become the town of Felling.[62] In 1902, the council moved to new administrative buildings at Sunderland Road, known thereafter as Felling Town Hall.[63] The urban council administered the Felling District until its final meeting, concluded with a rendition of the Hokey cokey, on 28 March 1974, when Felling was incorporated into the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead by the Local Government Act 1972.[64][65]

Immediately prior the creation of the metropolitan borough, Felling was an independent town but improved housing elsewhere and better transport links have seen the area decline in stature so that, today, Felling is simply a council ward in the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead.[66] It is approximately 3 square kilometres (1.2 sq mi) in area and has a population of 8,202.[67] It is represented by three councillors. In June 2012, they were Bill Dick, Paul McNally and Sonja Dickie.[68]

Felling is part of the Westminster parliamentary constituency of Gateshead. It was previously in the Gateshead East and Washington West constituency which was abolished by boundary changes before the 2010 UK General Election.[69] For many years the MP was Joyce Quin, who retired on 11 April 2005 and was awarded a life peerage into the House of Lords on 13 June 2006[70] and is now Baroness Quin. The present MP Ian Mearns, is a member of the Labour party and his office is in Gateshead.[71] He replaced Sharon Hodgson who successfully campaigned in the newly formed constituency of Washington and Sunderland West.[72] In the 2010 UK General Election, Mearns was elected with a majority of 12,549 over Frank Hindle. The swing from Labour to the Liberal Democrats was 3.9%.[73] Felling is in a safe Labour seat. Mearns' success in 2010 followed of Sharon Hodgson, who in the 2005 UK General Election polled over 60% of the votes cast[74] while in 2001, Joyce Quin was returned with a majority of 53.3%.[75]

Demography

| Felling compared (2001) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Felling[68] | Gateshead[76] | England[76] | |

| Total population | 7,299 | 191,151 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 97.7% | 98.4% | 90.9% |

| BME | 2.3% | 1.6% | 4.6% |

| Aged 0–19 | 23.2% | 24.2% | 26.32% |

| Aged 65+ | 17% | 17.3% | 15.9% |

| Male | 48.5% | 48.3% | 48.7% |

| Female | 51.5% | 51.7% | 51.3% |

According to the United Kingdom Census 2001, Felling has a population of 7,299—51.5% of the population are female, slightly above the national average, while 48.5% are male.[77] Only 2.3% of the population were from a black or other minority ethnic group (BME), as opposed to 9.1% of the national population.[67][76] The average life expectancy is 71 years for men in Felling and 75 years for women. These compare unfavourably to borough averages of 76 and 81 years respectively.[78]

The proportion of lone parent households varies hugely across the area; in High Felling the figure is 11.5%, in Central Felling it is 12.2% but in North Felling the figure is 22.3%. The latter is the second highest figure in Gateshead and all compare with a borough average of 11.5%.[79][80] A similar pattern emerges as regards households with dependent children; in Central and High Felling the proportions are low at 16.6% and 23.1%, while in North Felling the figure 34.8%. These compare to figures to 29.5% nationally and 28.4% in Gateshead.[81][82] The Index of Multiple Deprivation, which divides England into 32,482 areas and measures quality of life to indicate deprivation, splits Felling into several areas and in 2010 listed North Felling, Old Fold, Sunderland Road and Falla Park in the top 10% of all deprived areas in England in 2012.[67]

In 2011 however, there was a massive population increase from 7,299 a decade earlier to 8,908. The ethnic minority population has also increased from being 96.6% White British in 2001 to 92.3% in 2011.

| Felling compared 2011 | Felling | Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead |

|---|---|---|

| White British | 92.3% | 94.0% |

| Asian | 2.2% | 1.9% |

| Black | 1.1% | 0.5% |

Felling, like nearby Deckham, is a rapidly growing area with more and more people from other countries settling in the area. In 2011, 7.7% of Felling's population were non White British compared with only 3.4% in 2001.

| Felling Ethnicity | Census 2001 | Census 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| White | 97.7% | 95.4% |

| White British | 96.6% | 92.3% |

Transport

The suburb is bisected principally by the A184.[45] Built in 1959, the road is commonly referred to as the Felling bypass though it "is really nothing of the kind" as the road splits residential areas of Felling almost neatly in half.[86] Journey time by car or bus to Gateshead town centre from the western fringe is approximately seven minutes and twelve minutes into the centre of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, while the journey time from the eastern parts of Felling is approximately ten minutes longer.[87] Until the building of the bypass, the principal road in the settlement was B1426 Sunderland Road; a former turnpike road and tram route where civic and commercial buildings still stand as a testament to the road's past importance.[88] While diminished in stature today, Sunderland Road remains an integral local distributor.[89]

There are two Tyne and Wear Metro stations. Travelling towards Gateshead, the first is Felling Metro station, located between Sunderland Road and Mullberry Street, around three minutes walk from Felling town centre.[90][91] The station itself is described in one official document as "unwelcoming and even intimidating" which creates a negative impression[92] and, although the principal public transport hub, is underused by residents who often prefer to walk to Pelaw Metro rather than risk encountering anti-social behaviour at the station.[93] Another Metro station located west of the suburb, at Shelley Drive, is Gateshead Stadium Metro station.[91][94] This station to the west of Felling and is approximately five minutes walk from Gateshead International Stadium.[95]

Pelaw Metro station and Heworth Metro station are located in the east of the area.

Felling lies on three major bus routes into Gateshead; Split Crow Road/Crowhall Lane, Sunderland Road and the Felling Bypass. The provision through Crowhall Lane is particularly good.[96][97] The suburb is served by several bus services, such as the Orbit 51 which travels to Heworth Interchange and terminates at Gateshead, the 93/4 Loop which travels to the Team Valley and the "69 Pulse" which travels into the western Gateshead villages of Whickham and Blaydon.[98][99][100] All of the buses which serve Low Fell are operated by Go North East under the administration of Nexus.[101]

Culture

In 1963, Felling was twinned with Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray, France. When it was absorbed into Gateshead in 1974, the twinning arrangement was transferred to Gateshead.[102]

Listed buildings

A number of listed buildings are located in and around the town centre. Arguably the most significant is Crow Hall, a Grade II* listed building,[103] is an early 18th-century sandstone and ashlar, one-room deep building at Crowhall Lane.[104] The adjacent Crow Hall Cottage and gate piers are Grade II listed buildings.[105][106] At Victoria Terrace stands Felling post office; a two-story course sandstone building with quoins and a Welsh slate roof.[107] Close by is the Imperial Bingo Club, built as a dance hall in 1927 and converted to a bingo hall in 1930, at Victoria Square.[108] Both are Grade II listed buildings.[109][110] Also a Grade II listed building is Ardallan; the first house built at Holly-Hill field in Felling constructed of sandstone and with three sash windows.[111][112] The gates, gate piers and walls are also Grade II listed.[113] Almost immediately next door stands a house and shop at 35 Davison Street; another Grade II listed building.[114]

Travelling north, the old Town Hall building at Sunderland Road is a Grade II listed building.[115] Built in 1902 and designed Henry Miller, the Felling U.D.C surveyor, this is another ashlar and sandstone building in the Baroque style.[104][116] The five piers and lamp-holders guarding the town hall are also Grade II listed.[117] The Brandling Junction railway building, now an urban studies centre, has been restored and is also a Grade II listed building.[118] At the extreme north of the town at Riverside Park, the former engine house of Tyne Main Colliery, built in 1820, is also a Grade II listed building.[119]

Churches

There are two churches in Felling which are also listed buildings. Christ Church, at Carlisle Street, is a Grade II listed building[120] built in 1866 by Austin and Johnson.[121] Built in the early English style, there are two stained glass windows, added in 1874, and the north aisle was completed in 1903 by J Potts and Son.[104] The church has been in continuous use since opening and today the Anglican church continues to offer religious worship and contributes to the local community through a variety of outreach programmes.[122] Also a Grade II listed church is the Church of St Patrick at High Street.[123] A Roman Catholic church built between 1893–95 by Charles Walker of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, St Patrick's is a "bold though towerless"[104] sandstone, slate and ashlar building with considerable ornamentation to the exterior though the interior is considered "roomy but uninteresting".[104][124] Officially opened on St Patrick's Day in 1895, the church is a replacement for the older St Patrick's RC Chapel at Felling Shore.[125] The church presbytery is also a Grade II listed building.[126]

Parks and leisure

There are four principal parks. Arguably the most notable is Felling Park, a landscape park which envelops the old Town Hall buildings at the eastern end of Sunderland Road and the Holly Hill area. Opened in 1910, this park contains an open bandstand at the centre (but was taken down due to vandalism), tennis courts and a bowling green and a traditional children's play area.[127] In the area leading uphill from Sunderland Road to the park there are numerous bedding plants which "brighten up Sunderland Road every spring".[63] Felling Park was locally listed as of special local historic interest by Gateshead Council in 2004.[128] Sunderland Road Park is at the western end of Sunderland Road approaching Gateshead town centre.[129] This park is a former cemetery and at the front stands a Victorian water fountain replete with a religious inscription.[130] Built in 1895, the fountain had fallen victim to vandalism in recent years but this "important local landmark" was restored in 2011.[131] Also in Felling are Bede Community Park; a large, open space park at the centre of the residential development at Old Fold Road which contains a traditional play area[132] and Heworth Welfare Park; a smaller park to the south at Colpeth which also has a children's play area, installed in 2006, and an outdoor bowling green.[133][134]

The principal leisure facility in Felling is the Gateshead International Stadium. The original stadium was opened in 1955, on land reclaimed from chemical dereliction and at a cost of £30,000, by Jim Peters and contained a running and cycling track.[135][136] The stadium was fitted with a synthetic running track in 1974 and was subject to major expansion in the 1980s, when football, rugby and hockey pitches were added along with an indoor sports hall and weights room.[136] Said to have been the original driver of urban regeneration in Gateshead,[135] the venue has hosted various world class athletics events, including the European Cup in 1989 and 2000[note 4] and also the British Grand Prix, a Diamond League meet, between 2008–10.[137][138] Two sporting clubs are currently based at the stadium. These are Gateshead Harriers, an athletic club who count the present triple jump world record holder Jonathan Edwards in their past alumni,[139] and also Gateshead F.C. who currently play in the Conference National.[140]

Other leisure facilities include the Keelman's Way, a 14-mile designated cycle and walking route which stretches from Wylam station to Bill Quay and which passes along the riverbank at Felling Shore.[141] Named from the keelboats used to transport coal from the various collieries in the area,[141] the route was extended into Newburn in 2012 when a Gateshead blue plaque was laid in memory of its creator, Councillor Roy Deane.[142] Also at Felling Shore, at Green Lane, is Friar's Goose marina[143] and the adjacent Friar's Goose Water Sports Club, a privately owned and increasingly popular club predominantly attended by middle-aged patrons who undertake various activities such as sailing, yachting and angling on the River Tyne.[144][145] Felling Cricket Club has been based at High Heworth Lane at Felling since 1961 and compete locally,[146] and there are a wide selection of public houses, including the Wheatsheaf at Carlisle Street, the Blue Bell in Victoria Square, the Portland Arms at Split Crown Road and the Pear Tree Inn at Sunderland Road which are all locally listed as places of special local interest.[147]

Education

Felling is served by a number of primary schools. Colegate Community primary school, at Colegate West,[148] is a satisfactory school with well behaved pupils who make satisfactory progress.[149] Falla Park Community primary school on Falla Park Road is an average sized school where the number of pupils entitled to free school meals is well above the national average.[150] This is a good school where pupils perform consistently well at key stage two.[151] Also a good school is The Drive Community primary school; a smaller than average school which achieves good results despite being located in an area of "considerable social disadvantage".[152][153] To the north, at Mulberry Street, lies Brandling primary school; another good, smaller than average-sized school.[154] Bede Community primary school, at Old Fold Road, is in an area with a "high incidence of social and economic deprivation" with a very high proportion of children entitled to free school meals and with learning difficulties.[155] Here children do not achieve as well in examinations but instead enjoy a high level of personal development and so, according to the latest OFSTED report, this too is a good school.[156]

Roman Catholic school provision is also provided at Old Fold Road by St Wilfrid's R.C. primary school. This small school, which includes a specific provision for traveller families, is satisfactory according to the latest OFSTED report.[157] Alternative Catholic school provision had been available at St John the Baptist R.C. primary school, which also served Felling at Willow Drive but was closed down due to lack of pupils in the summer 2011 after 74 years of operation. The school is now a Jewish girls school.[158]

Secondary school provision is provided by Thomas Hepburn Community Academy at Swards Road.[159] The school has around 700 students enrolled and the number of students entitled to free school meals is more than twice the national average.[160] The latest inspection declared this to be a "satisfactory and improving" school where over 70% of students obtain 5 or more grade A* – C in GCSE examinations and where those children from economically deprived backgrounds achieve better than similar children nationally.[161]

Overall, levels of academic achievement in Felling are low. Only 59% of adults have 5 or more GCSEs at grade A* – C. This compares to a borough average of 80% and is the lowest figure in the borough. The figure falls to 33% when GCSE English and Mathematics are included; this is the second lowest figure in Gateshead and is lowered only by neighbouring Deckham. 28% of school pupils have a special educational need; the highest figure in the borough and 8% higher than the Gateshead average.[162]

Notable residents

Felling has a long history of producing professional footballers. Arguably the most notable of these is Chris Waddle.[163] Waddle, born 14 December 1960 and a lifelong Sunderland supporter,[164] was a professional footballer who played for Newcastle United, Tottenham Hotspur F.C. and Marseille and who won 62 caps for England.[165] Despite winning three league titles in France and playing in the 1991 European Cup Final, the skilful winger is probably most remembered for missing England's fifth penalty in the semi-final of the 1990 World Cup.[166][167]

Other footballers include Albert Watson, born in Felling in 1903, who made 373 appearances for Blackpool F.C. Watson is most remembered for scoring the "£10,000 goal" which saved the club from relegation in the 1930–31 season.[168] Peter Wilson was born in Felling in 1947[169] and emigrated to Australia in 1968 after failing to break into the first-team at Middlesbrough F.C.[170] Wilson, an uncompromising defender, made 64 appearances for Australia, including captaining the side during the 1974 World Cup finals.[170] A "fascinating character", he has not spoken publicly for two decades and lives as a recluse in Sydney .[171] Also from Felling is Kevin Arnott who played for Sunderland & Sheffield United amongst others. Not forgetting of course local cult hero James J Boyle who represented Gateshead FC.

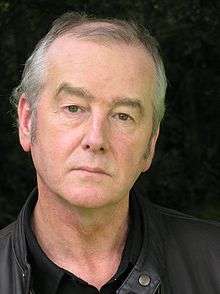

Author David Almond was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1951 and spent his childhood in Felling.[172] His 1998 work Skellig reflected the loss of his baby sister when he was a child growing up and was a critical success; winning the Carnegie Medal and Whitbread Book of the Year.[173][174] Now a "staple in secondary schools",[175] Skellig was adapted into film and opera in 2008.[176] Almond has since released several other works to critical acclaim, including Kit's Wilderness, The Fire Eaters and Clay.[177]

Also a resident of Felling was Sir Godfrey Hilton Thomson. Born in Carlisle in 1881, Thomson's mother returned to her native Tyneside soon after his birth and settled at Low Felling, where he attended school.[178] Thomson graduated from Kings College, Newcastle, becoming a Professor in 1920 and ultimately moving to the University of Edinburgh as Professor of Education in 1925.[179] An expert in psychometrics, he devised numerous groundbreaking tests for children, which were widely used in the 1920s, and published several books, including Instinct, Intelligence and Character (1924) and A Modern Philosophy of Education (1929).[178] Thomson's death in 1955 was described as a "great loss to psychology".[179]

Notes

- ↑ Charles Brandling (1733–1802) was another member of the family who became an MP, this time for Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in 1784. See Namier, 1995: 113–14

- ↑ Also known as "Brandling Main"

- ↑ Terminology: A colliery is a coal mine. A pit is a one shaft forming part of a colliery.

- ↑ Gateshead International Stadium is the only venue to have hosted that tournament twice. It is also slated to hold the event again in 2013; see Unknown (7 August 2012). "European Athletic– Calendar 2013". European Athletics.

References

- ↑ Mawer, 1920: 83–84

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mackenzie & Ross, 1834: 22

- ↑ Surtees, 1820: 85

- ↑ Surtees, 1820: 86

- 1 2 Newman, 1993: 56

- ↑ Surtees, 1820: 86–87

- 1 2 Surtees, 1820: 87

- ↑ Mackenzie, 1825: 470

- ↑ Hodgson, 1832: 414

- ↑ Browne Willis, 1750: 192

- ↑ Burke, 1852: 136

- 1 2 3 Hewitt (part three), 1990: 1

- ↑ Namier, 1995: 113

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis, 1848: 227

- 1 2 3 Mackenzie & Ross, 1834: 24

- 1 2 Baldwin, 1823: 502 at col.1

- 1 2 Unknown (2 August 2012). "Felling Colliery". Durham Mining Museum.

- ↑ Baldwin, 1823: 502

- 1 2 3 4 Hodgson, 1999

- ↑ Baldwin, 1823: 503 at col.1

- ↑ Baldwin, 1823: 504 at col.2

- ↑ Baldwin, 1823: 503–04

- ↑ Richardson, 1844

- ↑ Katie Davies (26 May 2012). "Parade for the Felling pit victims". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. (Retrieved 2 August 2012)

- 1 2 3 Whellan, 1856: 804

- ↑ MacKenzie and Ross, 1834: 22

- ↑ "Pattinson, Hugh Lee". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Unknown (1 January 2012). "Ten interesting facts about Felling". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. (Retrieved 3 August 2012)

- ↑ Herapath, 1839: 402

- ↑ Tindle, 2011: 11

- ↑ Unknown (2 August 2012). "History of Felling, County Durham". A vision of Britain through time. (Retrieved 3 August 2012)

- 1 2 Hewitt (part three), 1990: 1 at para. 5

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 11 at para. 2.2

- 1 2 Druitt, 1907: 68

- ↑ Druitt, 1907: 70

- 1 2 GVA, 2006: 11 at para. 2.3

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 13 at para. 2.9

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 13 at para. 2.10

- ↑ Hewitt (part three), 1990: 1 at para. 8

- ↑ NPSD, 2006: 44–45 at para. 4.39

- ↑ NPSD, 2006: 45 at para. 4.43

- ↑ FWF, 2012: 2

- ↑ FWF. 2012: 3

- ↑ Hewitt (part two), 1990: 2

- 1 2 NPSD, 2006: 30 at para. 2.96

- ↑ GE06, 2008: 4

- ↑ GE01, 2008

- ↑ GE06, 2008

- ↑ GE08, 2008

- ↑ GE01, 2008: 5

- ↑ GE06, 2008: 5

- ↑ GE08, 2008: 5

- ↑ GE01, 2008: 2

- 1 2 GE06, 2008: 2

- 1 2 GE08, 2008: 2

- ↑ NSPD, 2006: 26 at para. 2.90

- ↑ NPSD, 2006: 29 at para. 2.97

- ↑ NPSD, 2006: 29 at para. 2.98

- ↑ NPSD, 2006: 44 at para. 4.38

- ↑ Author unknown, "Local Elections 2012– Deckham", Gateshead MBC. Retrieved 12 July 2012

- ↑ Hewitt (Part two), 1990: 3–4

- ↑ Hewitt (Part one), 1990: 1

- 1 2 Tindle, 2011: 7

- ↑ Unknown (28 March 1974). "Felling Urban District. Last Meeting of the Council". Northern region Film and Television Archive.

- ↑ Manders, 1973: 26

- ↑ Arkenford, 2010: 60

- 1 2 3 FWF, 2012: 1

- 1 2 Unknown (12 July 2012). "Ward Information– Felling". Gateshead Council.

- ↑ Author Unknown, "Gateshead East and `Washington West", The Guardian (Retrieved 17 June 2012)

- ↑ Author unknown, "(Profile) Joyce Quin", They Work For You. Retrieved 14 April 2012

- ↑ Author unknown, "Contact Ian Mearns", IanMearns.Org. Retrieved 16 April 2012

- ↑ Author unknown, "Election 2010– Washington & Sunderland West", the BBC Online. Retrieved 14 April 2012

- ↑ Author unknown, "Election 2010– Gateshead", the BBC Online. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ Author unknown, "Election 2005", the BBC Online. Retrieved 14 April 2012

- ↑ Morgan, 2001: 67

- 1 2 3 Author unknown "Neighbourhood Statistics, Area Gateshead, Key figures for 2001", Office for National Statistics, UK Census 2001. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadPage.do?pageId=1004&tc=1463679865484&a=7&b=13689581&c=felling&d=14&e=15&f=24&g=6357396&i=1001x1003x1032x1004x1005&l=47&o=1&m=0&r=1&s=1463679865484&enc=1

- ↑ http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadPage.do?pageId=1004&tc=1463679865484&a=7&b=13689581&c=felling&d=14&e=15&f=24&g=6357396&i=1001x1003x1032x1004x1005&l=47&o=1&m=0&r=1&s=1463679865484&enc=1

- ↑ NPA, 2008: 14

- ↑ NPAN, 2008: 14

- ↑ NPA, 2008: 15

- ↑ NPAN, 2008: 15

- ↑ http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadTableView.do?a=7&b=13689581&c=felling&d=14&e=62&g=6357396&i=1001x1003x1032x1004&o=1&m=0&r=1&s=1463680164656&enc=1&dsFamilyId=2477

- ↑ http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadTableView.do?a=7&b=6275106&c=Gateshead&d=13&e=62&g=6357822&i=1001x1003x1032x1004&o=362&m=0&r=1&s=1463680524297&enc=1&dsFamilyId=2477

- ↑ http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadTableView.do?a=7&b=13689581&c=felling&d=14&e=62&g=6357396&i=1001x1003x1032x1004&o=1&m=0&r=1&s=1463680164656&enc=1&dsFamilyId=2477

- ↑ per Bernard Conlan, former MP for Gateshead: H/C Deb. "Felling Bypass", 14 December 1965. An online version may be available here courtesy of 'They Work For You'.

- ↑ Using Gateshead International Stadium and Heworth Metro station, at the western boundary, as reference points. See Unknown (29 July 2012). "The Loop: Timetable". Go-North East.

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 11 at para. 2.5

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 27 at para. 7.2

- ↑ Unknown (July 2012). "Metro Stations: Felling". Nexus.

- 1 2 NPSD, 2006: 46 at para. 4.47

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 27 at para. 7.4

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 27 at para. 7.9

- ↑ Unknown (July 2012). "Metro Stations: Gateshead Stadium". Nexus.

- ↑ Unknown (July 2012). "How to get to Academy for Sport at Gateshead International Stadium" (PDF). Gateshead College. at p. 2

- ↑ GVA, 2006: 27 at para. 7.10

- ↑ NPSD, 2006: 46 at para. 4.47

- ↑ "Route Map: Orbit". Go North East. 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ "Route Map: Loop". Go North East. 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ "Route Map: The Pulse". Go North East. 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ "What is Nexus?". Nexus. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Unknown (July 2012). "Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray". Gateshead Council.

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1355083, listing NGR: NZ2788461605

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pevsner, 1983: 271

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1025181, listing NGR: NZ2786561605

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1184918, listing NGR: NZ2787661577

- ↑ Cottrell, Bob (2004). "Images of England: Felling Post Office". English Heritage. (Retrieved 13 July 2012)

- ↑ Todd, J (2001). "Images of England: Imperial Bingo Hall". English Heritage. (Retrieved 13 July 2012)

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1025187, listing NGR: NZ2764361785

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1185123, listing NGR: NZ2761961794

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1184953, listing NGR: NZ2769461818

- ↑ Todd, J (2000). "Images of England: Ardallan". English Heritage. (Retrieved 13 July 2012)

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1355085, listing NGR: NZ2768861800

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1184922, listing NGR: NZ2772561820

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1299836, listing NGR: NZ2780561971

- ↑ Cottrell, Bob (2004). "Images of England: Gateshead District Housing Offices, Sunderland Road". English Heritage. (Retrieved 13 July 2012)

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1355088, listing NGR: NZ2781361983

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1299895, listing NGR: NZ2763762116

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1248567, listing NGR: NZ2752363148

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1184901, listing NGR: NZ2777962300

- ↑ Pevsner, 1983: 270

- ↑ Unknown (15 July 2012). "Christ Church Felling– About". Christ Church Felling.

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1184932, listing NGR: NZ2766261950

- ↑ Unknown (15 July 2012). "List Entry Summary–The Church of St Patrick". English Heritage.

- ↑ Unknown (1 January 2012). "Ten interesting facts about Felling". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. (date. Retrieved 15 July 2012)

- ↑ English Heritage list entry number 1025182, listing NGR: NZ2768861959

- ↑ Green, 1995: 43

- ↑ Quinn, 2004: 13

- ↑ Tindle, 2011: 8

- ↑ Tindle, 2011: 4

- ↑ Unknown (29 November 2011). "Restoration work springs fountains back to life". Gateshead Housing Company. (Retrieved 7 August 2012)

- ↑ Tindle (2011). "Great places to live...Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council. at p.4. Retrieved 7 August 2012

- ↑ Unknown (25 May 2006). "Game On". Gateshead Council. (Retrieved 7 August 2012)

- ↑ Unknown (January 2012). "Get Active– Going for Gold edition" (PDF). Gateshead Council. at p. 16. Retrieved 7 August 2012

- 1 2 Telford, 1988: 80

- 1 2 Unknown (7 August 2012). "Gateshead International Stadium– A Sporting history". Gateshead Council.

- ↑ Unknown (11 March 2008). "Gateshead sees Grand Prix boost". BBC. (Retrieved 7 August 2012)

- ↑ Unknown (2 March 2009). "IAAF to launch global Diamond League of 1 Day Meetings". IAAF.

- ↑ Unknown (13 October 2005). "Jonathan Edwards jumped at the chance to support Olympic hopeful at Lottery funded Gateshead Stadium". The National Lottery. (Retrieved 7 August 2012)

- ↑ Unknown (7 August 2012). "Gateshead F.C.– Club Info". Gateshead Football Club.

- 1 2 Tindle, 2011: 12

- ↑ Unknown (14 June 2012). "Keelman's Way cycle route link opened in Roy Deane's memory". BBC. (Retrieved 7 August 2012)

- ↑ Unknown (7 September 2010). "Appeal for witnesses after damaged boat sinks". Northumbria Police.

- ↑ Simpson, 2008: paras. 9–12

- ↑ Harris, 2009: paras. 10–12

- ↑ Unknown (2011). "History– Felling Cricket Club". Felling Cricket Club. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ↑ Quinn, 2004: 7

- ↑ Pringle, 2010: 1

- ↑ Pringle, 2010: 5–6

- ↑ Bennett, 2011: 3

- ↑ Bennett, 2011: 5–6

- ↑ Gilbert, 2011: 2

- ↑ Keenleyside, 2007: 3

- ↑ Cochrane, 2011: 1–3

- ↑ Dower, 2007: 3

- ↑ Dower, 2007: 4

- ↑ Pringle, 2011: 3–4

- ↑ Davies, 2011: 1–4

- ↑ Northern, 2011: 1

- ↑ Northern, 2011: 3

- ↑ Northern, 2011: 4

- ↑ FWF, 2012: 3

- ↑ Richards, 2011 at para. 1

- ↑ Unknown (October 2008). "One on One: Chris Waddle". Four Four Two.

- ↑ Sportsmail, 2011: para. 2

- ↑ Unknown (July 2012). "Chris Waddle: Wing wonder who proved a bigger hit in the Top 40 than from 12 yards". Daily Mirror.

- ↑ Harris, 1990

- ↑ Calley, 1992: 22

- ↑ Smyth, 2010 at para. 8

- 1 2 Unknown (2011). "Hall of Fame: Peter Wilson". Football Federation Australia. (Retrieved 13 July 2012

- ↑ Reuters, 2006

- ↑ Crown, 2010

- ↑ Jones, 2008 at paras. 1–5

- ↑ Crown, 2010 at para. 2

- ↑ Jones, 2010 at para. 3

- ↑ Unknown (14 April 2009). "Profiles: David Almond". BBC. (Retrieved 13 July 2012)

- ↑ Crown, 2010 at para. 6

- 1 2 Various (24 February 2011). "Godfrey Thomson". the University of Edinburgh. (Retrieved 13 July 2012)

- 1 2 Drever, 1955: 494

Bibliography

Academic texts and journals

- Baldwin (1823). The annual register or a view of the history, politics and literature for the year 1813. Baldwin, Cradock, & Joy.

- Burke, Bernard (1852). A genealogical and heraldic dictionary of the landed gentry of Great Britain & Ireland for 1852. Colburn & Co.

- Calley, Roy (1992). Blackpool: A complete record 1887–1990. Breedon Book Publishing Co. ISBN 1-873626-07-X.

- Drever, James (September 1955). Godfrey Hilton Thompson 1881–1955. The American Journal of Psychology.

- Druitt, E (September 1907). Accident returns– Extract for the accident at Felling on 26 March 1907. Board of Trade.

- Green, F (1995). A Guide to the Historic Parks and Gardens of Tyne and Wear. Tyne and Wear Specialist Conservation Team.

- Herapath (1839). Herapath's Railway Junction Vol.1. James Wyld.

- Hewitt, Joan (1990). File on Felling. Gateshead Central Library.

- Hodgson, John (1832). A history of Northumberland, in three parts, Part 2, Volume 2. E Walker.

- Hodgson, John (1999) [1812]. Felling Colliery 1812: An Account of the Accident (PDF). Picks Publishing. Retrieved 15 July 2013, online version available due to The Coal Mining History Resource Centre, Picks Publishing and Ian Winstanley.

- Lewis, Samuel (1848). A Topographical Dictionary of England, 7th Ed. Lewis.

- MacKenzie (1825). An Historical, Topographical, and Descriptive View of the County of Northumberland, and of Those Parts of the County of Durham Situated North of the River Tyne, with Berwick Upon Tweed, and Brief Notices of Celebrated Places on the Scottish Border. McKenzie and Dent. ISBN 1-147095-03-5.

- MacKenzie and Ross (1834). An Historical, Topographical and Descriptive View of the County Palatine of Durham. McKenzie and Ross. ISBN 1-150796-79-0.

- Manders, Francis William David (1973). A History of Gateshead. Gateshead Corporation. ISBN 0-901273-02-3.

- Mawer, Allen (1920). The place-names of Durham and Northumberland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1154956989.

- Namier, Lewis (1985). The House of Commons 1754–1790. Seeker & Warburg.

- Newman, P.R. (1993). The Old Service. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3752-2.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1983). The Buildings of England–County Durham. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09599-6.

- Richardson, Moses Aaron (1844). Local Historian's Table Book of Remarkable Occurrences Connected with the Counties of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, Northumberland and Durham. J.R Smith, London.

- Surtees, Robert (1820). The History and Antiquities of the county Palatine of Durham: vol.2, Chester ward. London Institute of Historical Research.

- Telford, Thomas (1998). Urban Regeneration. The Institute of Civil Engineers.

- Willis, Browne (1750). Notitia parliamentaria, or, An history of the counties, cities, and boroughs in England and Wales. Princeton University Press.

Journals, reports, articles and other sources

Where an abbreviation is used in the references this is indicated below in (brackets) at the end of the source name. When a source is available online, a link has been included.

- Arkenford (April 2010). "Newcastle and Gateshead Leisure Study" (PDF). Newcastle Council & Gateshead Council.

- Bennett, Janet (20–21 September 2011). "Inspection Report– Falla Park Community Primary School" (PDF). OFSTED.

- Cochrane, Irene (24–25 May 2011). "Inspection Report– Brandling Primary School" (PDF). OFSTED.

- Crown, Sarah (21 August 2010). "A life in writing: David Almond". The Guardian.

- Dower, Brian (29–30 November 2007). "Inspection Report– Bede Community Primary School" (PDF). OFSTED.

- Gilbert, Christine (26 April 2011). "The Drive Community Primary School; Ofsted's interim assessment" (PDF). OFSTED.

- GVA Grimley (February 2006). "Urban Design, Heritage & Character Analysis Report– North Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (GVA)

- GVA Grimley (February 2006). "North Felling Neighbourhood Profile Supporting Document" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (NPSD)

- Harris, Harry (5 July 1990). "We had the whole world in our hands". Daily Mirror.

- Henderson, Tony (5 April 2012). "Felling revamp gets green light from councillors". Newcastle evening Chronicle.

- Jones, Nicolette (25 October 2008). "David Almond:'Story is a kind of redemption'". The Daily Telegraph.

- Keenleyside, Alan (28–29 November 2007). "Inspection Report– The Drive Community Primary School" (PDF). OFSTED.

- King, Emma (22 July 2011). "Trial date set for Felling bypass road death". Newcastle Evening Chronicle.

- Northern, Lee (15–16 March 2011). "Thomas Hepburn Community Comprehensive School– Inspection Report" (PDF). OFSTED.

- Pringle, Kate (3–4 November 2010). "Inspection Report– Colegate Community Primary School" (PDF). OFSTED.

- Pringle, Kate (15–16 September 2011). "Inspection Report– St Wilfred's Roman catholic Voluntary Aided Primary School" (PDF). OFSTED.

- Quinn, David (February 2004). Report to Council- Local Lists of Buildings, and Parks and Gardens of Special Interest. Gateshead Council.

- Reuters (14 April 2006). "Socceroos' brotherly misfits made 1974 finals". ABC Sport Online.

- Richards, Linda (14 March 2011). "New guide shows hidden history of Felling". Newcastle Evening Chronicle.

- Smyth, Rob (24 March 2010). "The worst English champions ever (sort of)?: Englishmen Abroad". The Guardian.

- Sportsmail Reporter (3 May 2012). "Chris Waddle's son has some shoes to fill as young winger signs for Chesterfield". Daily Mail.

- Tindle (March 2011). "Discover Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council.

- Unknown (2012). "Felling Ward Factsheet" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (FWF)

- Unknown (2008). "GE06– Character Description Central Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (GE06)

- Unknown (2008). "GE01– Character Description North Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (GE01)

- Unknown (2008). "GE08– Character Description High Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (GE08)

- Unknown (July 2012). "How to get to Academy for Sport at Gateshead International Stadium" (PDF). Gateshead College.

- Unknown (November 2008). "Neighbourhood Profile East – Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (NPA)

- Unknown (November 2008). "Neighbourhood Profile East – North Felling" (PDF). Gateshead Council. (NPAN)

External links

![]() Media related to Felling, Tyne and Wear at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Felling, Tyne and Wear at Wikimedia Commons