Fecal–oral route

The fecal–oral route (or alternatively the oral–fecal route or orofecal route) is a route of transmission of a disease, when pathogens in fecal particles passing from one host are introduced into the oral cavity of another host. One main cause of fecal–oral disease transmission in developing countries is lack of adequate sanitation and, often connected to that problem, water pollution with fecal material.

Background

.jpg)

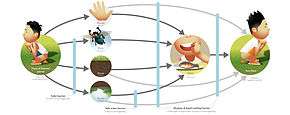

The foundations for the "F-diagram" being used today were laid down in a publication by Wagner, E. G and Lanoix, J. N. in the WHO monograph series no 39 explaining transmission routes and barriers to the transmission of diseases from the focal point of feces. Modifications have been made over the course of history to give modern day F-diagrams which has been widely used in many other sanitation publications. It was set up in a way that fecal–oral transmission pathways are shown to take place via water, hands, arthropods and soil. The sanitation barrier however when placed prevents the transmission of infection through the hands, water and food.[1]

The F-diagram is also used to show how proper sanitation (in particular toilets, hygiene, handwashing) can act as an effective barrier to stop transmission of diseases via fecal–oral pathways.

One approach to changing people's behaviors and stopping open defecation, the community-led total sanitation approach, uses "live demonstrations" of flies moving from food to fresh human feces and back to "trigger" villagers into action.[2]

Examples

The process of transmission may be simple or involve multiple steps. Some examples of routes of fecal–oral transmission include:

- water that has come in contact with feces (for example due to groundwater pollution from pit latrines) and is then not treated properly before drinking;

- by shaking someone's hand that has been contaminated by stool, changing a child's diapers, working in the garden or dealing with livestock or house pets.

- food that has been prepared in the presence of fecal matter;

- disease vectors, like houseflies, spreading contamination from inadequate fecal disposal such as open defecation;

- poor or absent hand washing after using the toilet or handling feces (such as changing diapers)

- poor or absent cleaning of anything that has been in contact with feces;

- sexual practices that may involve oral contact with feces, such as anilingus, coprophilia or "ass to mouth".

- eating feces, in children, or in a mental disorder called coprophagia

- eating soil (geophagia)

Diseases by pathogen type

Some of the diseases that can be passed via the fecal–oral route are (grouped by the type of pathogen involved in disease transmission):

- Bacteria

- Vibrio cholerae (cholera)

- Clostridium difficile (pseudomembranous enterocolitis)

- Shigella (shigellosis / bacillary dysentery)[3]

- Salmonella typhii (typhoid fever)[4]

- Vibrio parahaemolyticus[5]

- Escherichia coli[6]

- Campylobacter[7]

- Viruses

- Hepatitis A[8]

- Hepatitis E[9]

- Enteroviruses

- Norovirus acute gastroenteritis

- Poliovirus (poliomyelitis)

- Rotavirus[6] – Most of these pathogens cause gastroenteritis.

- Protozoans

- Entameba histolytica[6] (amoebiasis)

- Giardia (giardiasis[10])

- Cryptosporidium (cryptosporidiosis)

- Toxoplasma gondii[7] (toxoplasmosis)

- Helminths

- Other

Transmission of Helicobacter pylori by fecal–oral route has been demonstrated in murine models.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Wagner, E. G., and Lanoix, L. N. (1958). Excreta disposal for rural and small communities. (PDF). WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. p. 12.

- ↑ Kal, K and Chambers, R (2008) Handbook on Community-led Total Sanitation, Plan UK Accessed 2015-02-26

- ↑ Hale TL, Keusch GT (1996). Baron S, et al., eds. Shigella in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. (via NCBI Bookshelf) ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Giannella RA (1996). Baron S; et al., eds. Salmonella:Epidemiology in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. (via NCBI Bookshelf) ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Finkelstein RA (1996). Baron S; et al., eds. Cholera, Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139, and Other Pathogenic Vibrios in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. (via NCBI Bookshelf) ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Intestinal Parasites and Infection fungusfocus.com – Retrieved on 2010-01-21

- 1 2 "Stool-To-Mouth or Fecal–Oral Route of Transmission of Infection | Healthhype.com". www.healthhype.com. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ↑ Zuckerman AJ (1996). Baron S; et al., eds. Hepatitis Viruses in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. (via NCBI Bookshelf) ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Wang L, Zhuang H (2004). "Hepatitis E: an overview and recent advances in vaccine research". World J Gastroenterol. 10 (15): 2157–62. PMID 15259057.

- ↑ Meyer EA (1996). Baron S; et al., eds. Other Intestinal Protozoa and Trichomonas Vaginalis in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. (via NCBI Bookshelf) ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Cellini et al. (1998). "Evidence for an oral–faecal transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in an experimental murine model". APMIS 107(1–6): 477–484.