Fatimid architecture

The Fatimid architecture that developed in the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1167 CE) of North Africa combined elements of eastern and western architecture, drawing on Abbasid architecture, Byzantine and Coptic architecture and North African traditions; it bridged early Islamic styles and the medieval architecture of the Mamluks, introducing many innovations.

The wealth of Fatimid architecture was found in the main cities of Mahdia (921–948), Al-Mansuriya (948–973) and Cairo (973–1169). The heartland of architectural activity and expression during Fatimid rule was at al-Qahira, the old city of Cairo, on the eastern side of the Nile, where many of the palaces, mosques and other buildings were built.[1] Al-Aziz Billah (ruled 975–996) is generally considered to have been the most extensive of Fatimid builders, credited with at least thirteen major landmarks including the Golden Palace, the Cairo Mosque, a fortress, a belvedere, a bridge and public baths.

The Fatimid Caliphs competed with the rulers of the Abbasid and Byzantine empires, and indulged in luxurious palace building. Their palaces, their greatest architectural achievements, are known only by written descriptions, however. Several surviving tombs, mosques, gates and walls, mainly in Cairo, retain original elements, although they have been extensively modified or rebuilt in later periods. Notable extant examples of Fatimid architecture include the Great Mosque of Mahdiya, and the Al-Azhar Mosque, Al-Hakim Mosque, Juyushi and Lulua of Cairo.

Although heavily influenced by architecture from Mesopotamia and Byzantium, the Fatimids introduced or developed unique features such as the four-centred keel arch and the squinch, connecting square interior volumes to the dome. Their mosques followed the hypostyle plan, where a central courtyard was surrounded by arcades with their roofs usually supported by keel arches, initially resting on columns with leafy Corinthian capitals. They typically had features such as portals that protrude from the wall, domes above mihrabs and qiblas, and façade ornamentation with iconographic inscriptions, and stucco decorations. The woodwork of the doors and interiors of the buildings was often finely carved. The Fatimids also made considerable development towards mausoleum building. The mashad, a shrine that commemorates a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, was a characteristic type of Fatimid architecture.

Three Fatimid-era gates in Cairo, Bab al-Nasr (1087), Bab al-Futuh (1087) and Bab Zuweila (1092), built under the orders of the vizier Badr al-Jamali (r. 1074–1094), have survived. Though they have been altered over the centuries, they have Byzantine architectural features, with little trace of the eastern Islamic tradition. Recently a "Neo-Fatimid" style has emerged,[2] used in restorations or in modern Shia mosques by the Dawoodi Bohra, which claims continuity from the original Fatimid architecture.

Background

Origins

The Fatimid Caliphate originated in an Ismaili Shia movement launched in al-Salamiyah, on the western edge of the Syrian Desert, by Abd Allah al-Akbar, a claimed eight generation descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, through the prophet's daughter Fatimah. In 899 his grandson, to be known as Abd Allah al-Mahdi, became leader of the movement. He fled from his enemies to Sijilmasa in Morocco, where he proselytized under the guise of being a merchant.[3] He was supported by a militant named Abu Abd Allah al-Shi'i, who organized a Berber uprising that overthrew the Tunisian Aghlabid dynasty, and then invited al-Mahdi to assume the position of imam and caliph. The empire grew to include Sicily and to stretch across North Africa from the Atlantic to Libya.[4] The Fatimid caliphs built three capital cities, which they occupied in sequential order: Mahdia (921–948) and al-Mansuriya (948–973) in Ifriqiya and Cairo (973–1169) in Egypt.

Ifriqiya

Mahdia was a walled city located on a peninsula that projected into the Mediterranean from the coast of what is now Tunisia, then part of Ifriqiya.[lower-alpha 1][5] The Carthaginian port of Zella had once occupied the site. Mahdia was founded in 913 by Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah, the first Fatimid imam, and later was the port from which the Fatimid invasion of Egypt was launched. al-Mahdi built the Great Mosque of Mahdiya, the earliest Fatimid mosque, in the new city.[5] The other buildings erected nearby at that time have since disappeared, but the monumental access gate and portico in the north of the mosque are preserved from the original structure.[6]

Al-Mansuriya, near Kairouan, Tunisia, was the capital of Fatimid Caliphate during the rules of the Imams Al-Mansur Billah (r. 946–953) and Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah (r. 953–975).[7] Built between 946 and 972, it was a circular walled city holding elaborate palaces surrounded by gardens, artificial pools and water channels.[8] The caliph Al-Mu'izz moved from the city to the new city of al-Qāhira (Cairo) in 973, but Al-Mansuriya continued to serve as the provincial capital.[9] In 1057 it was abandoned and destroyed. Any useful objects or materials were scavenged during the centuries that followed. Today only faint traces remain.[10]

Egypt

_-_TIMEA.jpg)

The Fatimid general, Jawhar al-Siqilli built a new palace city near to Fusṭāt upon conquering Egypt in 969, which he at first called al-Manṣūriyya after the capital in Tunisia. When Al-Mu'izz arrived in 973, the name was changed to al-Qāhira (Cairo). The new city incorporated elements of the design of Al-Mansuriya, although it was rectangular rather than circular in plan.[11] Both cities had mosques named al-Azhar after the Prophet's daughter, Fatima al-Azhar, and both had gates named Bab al-Futuh and Bab Zuwaila.[4] Both cities had two palaces, for the caliph and for his heir, opposite and facing each other.[11]

Al-Aziz Billah (955–996) is generally considered to have been the most extensive of Fatimid builders.[12] Aided in part by funds generated through his father al-Mu'izz's tax reforms, Al-Aziz is credited with at least 13 major building works during this reign from 975 until his death, including the Golden Palace, the Cairo Mosque, a fortress, a belvedere, a bridge and public baths.[12] His mother, Durzan, widow of al-Mu'izz, was also responsible for ordering the commencement of building projects, mainly in the Qarafa area, ordering construction of the second mosque in Cairo, Jami al-Qarafa Mosque, in 975.[12] Similar to the first mosque, Al-Azhar Mosque, it had some fourteen gates but was later destroyed by fire, leaving only its "green mihrab".[12] Durzan is also credited with ordering construction of the Qarafa Palace, a public bath, cistern, or pool, and a royal garden and hydraulic pump for the Abu 'l-Ma'lum fortress.[13] She also ordered a well to be built in the courtyard of Ibn Tulun Mosque in 995, a pavilion overlooking the Nile called Manazil al-izz, and her own mausoleum in Qarafa.[13]

Badr al-Jamali was also a noted builder, sponsoring numerous state architectural projects and restoration works during his rule from 1074–1094, particularly with mosques, restoring minarets in Upper Egypt and building mosques in Lower Egypt.[14] He also built many of the gates and fortifications in Cairo.

Architectural style

According to Ira M. Lapidus, public architecture under the Fatimids was an "extension of the ceremonial aspects of the royal court", and was also intricately made.[15] Fatimid architecture drew together decorative and architectural elements from the east and west, and spanned from the early Islamic period to the Middle Ages, making it difficult to categorize.[16] The architecture that developed as an indigenous form under the Fatimids incorporated elements from Samarra, the seat of the Abbasids, as well as Coptic and Byzantine features.[17] Most early buildings of the Fatimid period were of brick, although from the 12th century onward stone gradually became the chief building material.[18] The Fatimids combined elements of eastern and western architecture, drawing on Abbasid, North African, Greek and indigenous Coptic traditions, and bridged between the early Islamic styles and medieval architecture of the Mamluks.[19] The Fatimids were unusually tolerant of people with different ethnic origins and religious views, and were adept at exploiting their abilities.[20] Thus many of the works of Fatimid architecture reflect architectural details imported from Northern Syria and Mesopotamia, probably in part due to the fact that they often employed architects from these places to construct their buildings.[21] Fatimid architecture in Egypt drew from earlier Tulunid styles and techniques, and used similar types of material.[22] While also consciously adhering to Abbasid architectural concepts, the architecture is more influenced by Mediterranean cultures and less by Iranian.[23]

While Fatimid architecture followed traditional plans and aesthetics, it differed in architectural details such as the massive portals of some mosques and their elaborate façades.[23] Scholars such as Doğan Kuban describe Fatimid architecture as "inventive more in decoration than in broad architectural concept", although he acknowledges that the Fatimids contributed to a distinct style of mosque.[24] The Fatimids introduced or developed the usage of the four-centreed keel arch and the muqarnas squinch, a feature connecting the square to the dome. The muqarnas squinch was a complex innovation. In it a niche was placed between two niche segments, over which there was another niche. It is possible that this design had Iranian inspiration. A similar system was applied to window building.[25] According to De Lacy O'Leary, the horse-shoe arch was developed in Egypt under Fatimid rule and is not of Persian origin as is commonly thought.[26]

Palaces

The palaces of the Caliphs, their greatest architectural achievements, have been destroyed and are known only from written descriptions.[27] The heartland of architectural activity and expression during Fatimid rule was at al-Qahira, on the outskirts of Cairo on the eastern side of the Nile, where many of the palaces, mosques and other buildings were built.[1] The Caliphs competed with their rivals of the Abbasid and Byzantine empires, and were known to indulge in furnishing their palaces with "extraordinary splendor".[15] The palaces had gold rafters to support the ceilings and Caliphs typically asked for a golden throne encased with a curtain similar to those of the rulers of the Abbasids and Byzantines.[15] Furniture and ceramics were elegantly adorned with motifs of birds and animals which were said to bring good luck, and depictions of hunters, and musicians and dancers of the court which reflected the exuberance of Fatimid palace life.[28] Fountains were installed in the palaces to cool the atmosphere.[15]

Mausoleums

The mashad is a characteristic type of Fatimid building, a shrine that commemorates a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. The tombs of the Fatimid caliphs were also treated as shrines.[25] Most of the mashhads were straightforward square structures with a dome, but a few of the mausoleums at Aswan were more complex and included side rooms.[23] During the rule of al-Hafiz (r. 1130–1149) several mausoleums and mosques were rebuilt to honour notable female figures in Shi'i history. The caliphs also built tombs for their wives and daughters.[29]

Most of the Fatimid mausoleums have either been destroyed or have been greatly altered through later renovations.[19] The Mashad al-Juyushi, also called Mashad Badr al-Jamali, is an exception. This building has a prayer hall covered with cross-vaults, with a dome resting on squinches over the area in front of the mihrab. It has a courtyard with a tall square minaret. It is not clear whom the mashhad commemorates.[19] Two other important mashads from the Fatimid era in Cairo are those of Sayyida Ruqayya and Yayha al-Shabib, in the Fustat cemetery. Sayyida Ruqayya, a descendant of Ali, never visited Egypt, but the mashhad was built to commemorate her. It is similar to al-Juyushi, but with a larger, fluted dome and with an elegantly decorated mihrab.[30]

Mosques

The plan and decoration of Fatimid mosques reflect Shiite doctrine and that the mosques were often used for royal ceremonial purposes.[31] The characteristic architectural styles of Fatimid mosques include portals that protrude from the wall, domes above mihrabs and qiblas, porches and arcades with keel-shaped arches supported by a series of columns, façade ornamentation with iconographic inscriptions and stucco decorations.[32] The mosques followed the hypostyle plan, where a central courtyard was surrounded by arcades with their roofs usually supported by keel arches, initially resting on columns with Corinthian capitals. The arches held inscription bands, a style that is unique to Fatimid architecture.[27] The later columns often had a bell-shaped capital with the same shape mirrored to form the base. The prayer niche was architecturally more elaborate, with features such as a dome or transept.[27] The Fatimid architects built modified versions of Coptic keel-arched niches with radiating fluted hoods, and later extended the concept to fluted domes.[27] The woodwork of the doors and interiors of the buildings was often finely carved.[16]

Early Fatimid mosques such as the mosque of the Qarafa did not have a minaret.[33] Later mosques built in Egypt and in Ifriqiya incorporated brick minarets, which were probably part of their original designs. These were derived from early Abbasid forms of minaret.[34] Minarets later evolved to the characteristic mabkhara (incense burner) shape, where a lower rectangular shaft supported an octagon section that was capped by a ribbed helmet.[27] Almost all of Cairo's Fatimid minarets were destroyed by an earthquake in 1303.[35]

Some "floating" mosques were located above shops.[27] For the first time, the façade of the mosque was aligned with the street and was elaborately decorated. The decorations were in wood, stucco and stone, including marble, with geometrical and floral patterns and arabesques with Samarran and Byzantine origins. The decorations were more complex than the earlier Islamic forms and more carefully adapted to structural constraints.[27] The imposing architecture and decoration of Fatimid buildings such as the al-Hakim mosque provided a backdrop that supported the dual role of the Fatimid caliph as both religious and political leader.[22]

Great Mosque of Mahdiya

The Great Mosque of Mahdiya was built in Mahdia, Tunisia, in 916 CE (303–304 in the Islamic calendar), on an artificial platform "reclaimed from the sea" as mentioned by the Andalusian geographer Al-Bakri, after the founding of the city in 909 by the first Fatimid imam, Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah.[36] Internally, the Great Mosque had a layout similar to other mosques in the region. A transverse aisle paralleled the qibla wall, with nine aisles at right angles to the transverse. The original qibla wall was destroyed by sea erosion and had to be rebuilt, reducing the size of the prayer hall.[5] Like other mosques in the region, the orientation of the qibla differs significantly from the "true" great circle route to Mecca.[37]

Unlike other North African mosques, the Great Mosque did not have minarets, and had a single imposing entrance.[5] This is the first known example of a projecting monumental porch in a mosque, which may have been derived from the architecture of secular buildings.[38] The mosque at Ajdabiya in Libya had a similar plan, although it did not have the same monumental entrance. Like the Mahdiya mosque, for the same ideological reasons, the Ajdabiya mosque did not have a minaret.[39]

Al-Azhar Mosque

The Al-Azhar Mosque was commissioned by the Caliph Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah for the newly established capital city of Cairo. Its name is a tribute to the name of Fatima Al-Azhar, the daughter of the Prophet Mohammed.[40] Jawhar al-Siqilli, commander of the Fatimid army started construction of the mosque in 970. It was the first mosque established in the city.[41][lower-alpha 2] The first prayers were held there in 972, and in 989 the mosque authorities hired 35 scholars, making it a teaching centre for Shia theology.[41] A waqf for the mosque was established in 1009 by Caliph al-Hakim.[32]

The Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo seems to have had a similar projecting entrance to the Great Mosque of Mahdiya.[43] The original building had an open central courtyard with three arcades. Its layout was similar to the Kairouan and Samarra mosques. These had round arches on pre-Islamic columns with Corinthian capitals.[41] There were three domes (indicative of the location of the prayer hall), two at the corners of the qibla wall and one over the prayer niche, and a small brick minaret over the main entrance. The gallery around the courtyard had series of columns and the prayer hall, which had the domes built over it, had five more rows of five pillars.[40]

Minor alterations were made by the Caliphs Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in 1009 and Al-Amir bi-Ahkami l-Lah in 1125. The Caliph al-Hafiz (1129–1149) made significant further changes, adding a fourth arcade with keel arches, and a dome with elaborate carved stucco decorations in front of the transept.[44] Since then, the mosque has been greatly enlarged and modified over the years.[41] Of the original building little remains other than the arcades and some of the stucco decoration.[44]

Mosque of the Qarafa

An unusually detailed description of the mosque of the Qarafa in Cairo, built by two noblewomen in 976, has been left by the historian al-Quda'i, who died around 1062–1065.[45] He said,

This mosque had a lovely garden to its west, and a cistern. The door by which one enters has large mastabas. The middle [of the mosque] is under the high manar, which has iron sheets on it. [It runs] from the door right up to the mihrab and the maqsurah. It has fourteen square doors of baked brick. In front of all the doors is a row of arches; each arch rests on two marble columns. There are three ṣufūf.[lower-alpha 3] [The interior] is carved in relief and decorated in blue, red, green and other colors, and in certain places, painted in a uniform tone. The ceilings are entirely painted in polychrome; the intrados and the extrados of the arcades supported by columns are covered with paintings of all different colors.[45]

It seems probable from this description that the mosque had a portal that projected from the wall, as did the earlier Great Mosque of Mahdiya. In other respects it seems to have resembled the al-Azhar mosque in layout, architecture and decoration.[45] Although the geographers al-Muqaddasi and Ibn Hawqal both praised this mosque, neither left specific descriptions of this or any other mosque. Thus Ibn Hawqal says of it only that, "It is one of the mosques distinguished by the spaciousness of its court, elegance of construction, and the fineness of its ceilings."[33]

Al-Hakim Mosque

The Al-Hakim Mosque is named after Imam Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (985–1021), the third Fatimid caliph to rule in Egypt. Construction of the mosque started in 990.[32] In 1002–3 Caliph al-Hakim ordered completion of the building. The southern minaret has an inscription with his name and the date of 393 (1003). Significant changes were made to the minarets in 1010. At first the mosque was outside the city walls, but when Badr al-Jamali rebuilt the walls he enclosed a larger area, and the north wall of the mosque became part of the new stone city wall. The mosque was badly damaged in the 1303 earthquake, and suffered further damage in later years. By the nineteenth century it was ruined, but has since been reconstructed.[46]

The mosque is an irregular rectangle with four arcades that surround the courtyard. As with the Ibn Tulun mosque, the arches are pointed and rest on brick piers. It resembles the al-Azhar mosque in having three domes along the qibla wall, one at each corner and one over the mihrab. Also like al-Azhar, the prayer hall is crossed by a transept at right angles to the qibla.[46] This wide and tall central aisle leading to the prayer niche borrows from the Mahdiya mosque's design.[47] The al-Hakim mosque differs from the al-Azhar and Ibn Tulun mosques in having two stone minarets at the corners of the stone façade, which has a monumental projecting portal like the Mosque of Mahdiya.[46]

Other Cairo mosques

The Lulua Mosque, located in the southern cemetery of the Moqattam hills, was built in 1015–16 during the reign of the third Caliph al-Hakim. The mosque was built on a promontory of limestone and consisted originally of a three-storey tower-like structure built over a rectangular plan. It exhibited typical aspects of the Fatimid architectural style, with portals with slight protrusions, mihrabs and qibla walls, several domes, and columned porches with triple arches or keel-shaped arches.The mosque partially collapsed in 1919, but was later refurbished in 1998 by the Dawoodi Bohras.[48][49]

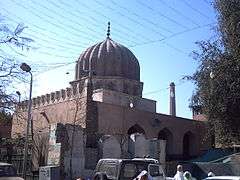

The Juyushi Mosque was built by Badr al-Jamali, the "Amir al Juyush" (Commander of Forces) of the Fatimids. The mosque was completed in 1085 under the patronage of the then Caliph and Imam Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah. It was built on an end of the Mokattam Hills which would ensure a view of the Cairo city.[50]

The Aqmar Mosque was built in the under vizier al-Ma'mun al-Bata'ihi during the caliphate of Imam Al-Amir bi-Ahkami l-Lah. The mosque is located on north Muizz Street. It is notable for its façade, which is elaborately decorated with inscriptions and geometric carving. It is both the first mosque in Cairo to have such decoration, and also the first to have a façade which follows the line of the street, built at an angle to the rectangular hypostyle hall whose orientation is dictated by the qibla direction.[51]

Cairo fortifications

A new city wall was built around Cairo on the orders of the vizier Badr al-Jamali (r. 1074–1094). Cairo had expanded beyond the original city walls, and the city faced threats from the east, notably by the Turkoman Atsiz ibn Uvaq, commander of the Seljuk army. In fact, the fortifications were never put to the test. Three of the gates in the new walls have survived: Bab al-Nasr (1087), Bab al-Futuh (1087) and Bab Zuweila (1092). Bab al-Futuh and Bab Zuweila were built at the northern and southern ends of Muizz Street, the main axis of Fatimid Cairo.[52]

Al-Jamali, an Armenian in origin, is said to have employed Armenians from the north of Mesopotamia as well as Syrians in his extensive building works.[52] Each gate was said to have been built by a different architect.[53] The gates have Byzantine architectural features, with little trace of the Islamic tradition.[54] According to Maqrīzī, the gates were built by three Christian monks from Edessa, who had fled from the Saljūqs. There are no surviving structures similar to the gates near Edessa or in Armenia, but stylistic evidence indicates that Byzantine origins for the design are entirely plausible.[54]

Al-Jamali preferred stone as the medium for his building works, introducing a new style into Cairo architecture.[52] All three gates have massive towers linked by curtain walls above the passageways. They introduced architectural features new to Egypt including the pendentives that support the domes above the passageways of the Bab al-Futuh and Bab Zuweila gates, and intersecting barrel vaults.[52] Use of semi-circular and horizontal arches, and lack of pointed arches, represented a departure from normal Fatimid architecture, probably taken from Syrian examples, and were never widely used during the Fatimid period. The use of stone also reflects Syrian tastes.[52]

The passageways through each of the gates are 20 metres (66 ft) long, and have vaulted ceilings with hidden machicolation openings in their ceilings. The lower part of each tower is of solid stone, while the upper third has a vaulted room with arrowslits.[53] An unusual feature of the wall near Bab al-Nasr is a stone latrine which appears like a balcony.[52] The wall between Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh contains an inscription of Quranic texts in Kufic characters.[55]

Bab al-Futuh

Bab al-Futuh is a gate in the north wall of the old city, built in 1087. It stands at the northern end of Muizz Street.[52] The name "Futuh" means "conquest".[56] the gate had rounded towers, with both of their façades incorporating a design of two parallel carved lines with loops between them. No earlier use of this decorative style is known, although it became common in the Mamluk period. There are carved brackets above the entrance arch, two of which have the head of a ram. This appears to be a survival of pre-Islamic symbolism.[56] However, Fatimid arabesques decorate the brackets.[52]

Bab al-Nasr

Bab al-Nasr is a massive fortified gate built in 1087 with rectangular stone towers. The name means "Gate of Victory". The entrance vestibule is cross-vaulted. There are two shallow domes over the upper levels of the towers. The walls are decorated with shields and swords, possibly Byzantine in design.[55] Many French inscriptions on the Bab al-Nasr indicate use of the fort by Napoleon's soldiers, including "Tour Courbin" and "Tour Julien".[52]

Bab Zuweila

Bab Zuweila (or Zuwayla) is a medieval gate built in 1092. It is the last remaining southern gate from the walls of Fatimid Cairo.[57] The gate is today commonly called Bawabet El Metwalli.[58] Its name comes from bab, meaning "door", and Zuwayla, the name of a North African tribe. The towers are semi-circular. Their inner flanks have lobed arches as decorations, a North African motif introduced to Egypt by the Fatimids. The vestibule to the right contains a half-domed recess with elegantly carved arches at each corner.[54] The gates were massive, weighing four tons.[58] The gates today have two minarets, open to visitors, from which the area may be viewed.[59][lower-alpha 4] Additions were made during the 15th century.[60]

Restorations and modern mosques

The Fatimid buildings have gone through many renovations and restructurings in different styles from the early Mamluk period to modern times.[61] The Fakahani Mosque exemplifies this process. It was built in the Fatimid period, either as a suspended mosque (one with shops underneath it) or with a high basement.[62] After the earthquake of 1302 it was rebuilt. In 1440 an ablution basin was added, and early in the Ottoman period a minaret was built.[62] The amir Ahmad Katkhuda Mustahfazan al-Kharbutli in 1735 ordered a major reconstruction, almost all of the original building being replaced apart from two doors.[62] These finely carved doors were registered as a historical monument in 1908 by the committee of conservation, and the building itself was registered in 1937.[62][63]

The Dawoodi Bohra, a group of around one million Ismaili Shi'ites who trace their faith back to converts from the Hindu faith during the time of the Fatimid caliph Al-Mustansir Billah (1029–1094),[64] have been engaged in restorations of the Cairo mosques since the 1970s. Aside from respecting their heritage, the purpose of the campaign to restore Fatimid architecture in Cairo is to encourage

| Look up ziyaret in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

ziyaret, a pilgrimage which aims to increase the cohesion of the Bohra community internationally.[65] These activities have drawn negative comments from critics in Europe and America who believe that the mosques should be preserved in their current state.[66]

In November 1979 the first newsletter of the Society for the Preservation of the Architectural Resources of Egypt wrote a scathing report of the Bohras' renovation of the al-Hakim mosque, saying "Though their method of financing the project is intriguing, their concrete arcades can only be deplored." However, when the mosque was re-opened a year later the Egyptian Gazette was complimentary about the transformation of the run-down building, achieved without resort to public aid.[67]

The restorations have significantly changed the buildings from their prior state. Helwan marble has been used extensively on both interior and exterior surfaces, and inscriptions in the interior have been gilded. Motifs and designs have been copied from one mosque to another. The qibla bay of the al-Hakim mosque, which had been irreparably damaged, was replaced by a version in marble and gilt of the mihrab of al-Azhar mosque.[68] The Lu'lu'a Mosque, formerly a ruin, has been rebuilt as a three-story building somewhat like Bab al-Nasr, with decorative elements from al-Aqmar and al-Hakim. Silver and gold grilles now enclose tombs in mosques and mausoleums. Arches, particularly in groups of three, are considered "Fatimid", regardless of their shape. The result is what could be termed "Neo-Fatimid" architecture, now found in new Bohra mosques around the world.[69] The Aga Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah, leader of the Ismaili sect, was buried in 1957 in a mausoleum built in this neo-Fatimid style.[70] In some cases this style incorporates elements that are clearly from a different period. All but one of the Fatimid minarets were destroyed by an earthquake in 1303, and later rebuilt by the Mamluks, but replicas of these minarets are used in Neo-Fatimid mosques.[35]

See also

To Read

Gallery

-

Walls in Cairo

-

Cairo gate of Bab al-Futuh

-

Cairo gate of Bab al-Futuh

-

Bab al-Nasr gate - detail

-

Al-Aqmar Mosque, Cairo - interior

-

Al-Aqmar Mosque, Cairo showing "keel arches", so called because their shape resembles that of the keel of an upturned boat.

-

Al-Aqmar Mosque, Cairo - exterior

-

Masjid jamea al anwar, Cairo

-

Great Mosque of Mahdiya, Tunisia

-

Entrance of the Great Mosque of Mahdiya, Tunisia

-

Interior of Masjid Juyushi, Cairo

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Ifriqiya was the western part of the Fatimid caliphate, covering the northern part of what today is western Libya, Tunisia and eastern Algeria.

- ↑ The congregational Mosque of Amr ibn al-As is the oldest mosque in modern Cairo, built in 640–641. However, the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As was built in the camp of Fustat. Cairo has expanded and now includes Fustat within its borders.[42]

- ↑ Suffa / ṣufūf: arcades.[45]

- ↑ The Mosque of Sultan al-Muayyad, completed in 1421, was built beside the Bab Zuweila gate by the Sultan al-Muyyad. He destroyed part of the city wall to make room, and placed the minarets on the gateway rather than the mosque.[60]

Citations

- 1 2 Jarzombek & Prakash 2011, p. 384.

- ↑ Sanders 2008, p. 130.

- ↑ Yeomans 2006, p. 43.

- 1 2 Yeomans 2006, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 Petersen 2002, p. 168.

- ↑ Hadda 2008, p. 72–73.

- ↑ Halm 1996, p. 331, 345.

- ↑ Ruggles 2011, p. 120.

- ↑ Tracy 2000, p. 234.

- ↑ Barrucand & Rammah 2009, p. 349.

- 1 2 Safran 2000, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 4 Cortese & Calderini 2006, p. 166.

- 1 2 Cortese & Calderini 2006, p. 167.

- ↑ Cortese & Calderini 2006, p. 170.

- 1 2 3 4 Lapidus 2002, p. 285.

- 1 2 Bloom 2008, p. 231.

- ↑ Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 9.

- ↑ Fage 1975, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Petersen 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ Daftary 1992, p. 254.

- ↑ Dadoyan & Parsumean-Tatoyean 1997, p. 147.

- 1 2 The Art of the Fatimid Period.

- 1 2 3 Kuiper 2009, p. 164.

- ↑ Kuban 1974, p. 1.

- 1 2 Kuiper 2009, p. 165.

- ↑ O'Leary 2001, p. 105.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 10.

- ↑ Lapidus 2002, p. 286.

- ↑ Cortese & Calderini 2006, p. 164.

- ↑ Petersen 2002, p. 45–46.

- ↑ Robinson 1996, p. 269.

- 1 2 3 Fatimid Mosques in Cairo - MIT.

- 1 2 Grabar 1988, p. 8.

- ↑ Gibb et al. 1996, p. 50.

- 1 2 Sanders 2004, p. 141.

- ↑ Hadda 2008, p. 72.

- ↑ Holbrook, Medupe & Urama 2008, p. 155.

- ↑ Ettinghausen 1972, p. 58.

- ↑ Petersen 2002, p. 86–87.

- 1 2 Fatimad Architecture.

- 1 2 3 4 Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 58.

- ↑ Homerin 2001, p. 347.

- ↑ Wijdan 1999, p. 142.

- 1 2 Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 Grabar 1988, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 63.

- ↑ Yeomans 2006, p. 59.

- ↑ Masjid al-Lu'lu'a.

- ↑ Williams 2008, p. 128–129.

- ↑ Saifuddin 2002.

- ↑ Dunn 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bab al-Nasr - Archnet.

- 1 2 Petersen 2002, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 72.

- 1 2 Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 68.

- 1 2 Behrens-Abouseif 1992, p. 69.

- ↑ Eyewitness Travel: Egypt, p. 103.

- 1 2 Hebeishy 2010, p. 217.

- ↑ Firestone 2010, p. 136.

- 1 2 Hurley & Ennis 2002, p. 97.

- ↑ Sanders 2008, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 Bloom 2008, p. 234–235.

- ↑ BloomBlair 2009, p. 330.

- ↑ Sanders 2008, p. 116.

- ↑ al Sayyad 2011, p. 57.

- ↑ Sanders 2008, p. 117.

- ↑ Sanders 2008, p. 118.

- ↑ Sanders 2008, p. 126.

- ↑ Sanders 2008, p. 127.

- ↑ Kerr 2002, p. 69.

Sources

- "Bab al-Nasr". Archnet.org. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Barrucand, Marianne; Rammah, Mourad (2009-10-31). "Sabra al-Mansuriyya and her neighbors during the first half of the eleventh century: Investigations into stucco decoration". Muqarnas. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17589-1. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1992). Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction. BRILL. p. 9. ISBN 978-90-04-09626-4. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2008-12-30). "The "Fatimid" Doors of the Fakahani Mosque in Cairo". Muqarnas, Volume 25: Frontiers of Islamic Art and Architecture: Essays in Celebration of Oleg Grabar's Eightieth Birthday. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17327-9. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture: Delhi to Mosque. Oxford University Press. pp. 330–. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- Cortese, Delia; Calderini, Simonetta (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1733-3.

- Dadoyan, Seta B.; Parsumean-Tatoyean, Seda (1997). The Fatimid Armenians: Cultural and Political Interaction in the Near East. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10816-5.

- Daftary, Farhad (1 July 1992). Ismāʻı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- Dunn, Jimmy (2013). "Egypt: Cairo Muslim - El-Aqmar Mosque (Gray Mosque)". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Ettinghausen, Richard (1972). From Byzantium to Sasanian Iran and the Islamic World: Three Modes of Artistic Influence. Brill Archive. p. 58. ISBN 978-90-04-03509-6. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- Eyewitness Travel: Egypt. London: Dorlin Kindersley Limited. 2007 [2001]. ISBN 978-0-7566-2875-8.

- Fage, John D. (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- "Fatimad Architecture". History for kids organization. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Fatimid Mosques in Cairo". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Firestone, Matthew (2010-09-15). Egypt. Lonely Planet. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-74220-332-4. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Gibb, H. A. R.; Donzel, E. van; Bearman, P. J.; van Lent, J. (1996). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. XIII Muqarnas. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10633-8. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- Grabar, Oleg (1988-03-01). Muqarnas, Volume 4: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. BRILL. p. 7. ISBN 978-90-04-08155-0. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- Hadda, Lamia (2008). Nella Tunisia medievale. Architettura e decorazione islamica (IX-XVI secolo). Naples: Liguori editore. ISBN 978-88-207-4192-1.

- Halm, Heinz (1996). Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10056-5. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Hebeishy, Mohamed el (2010-06-24). Frommer's Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-470-90682-8. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Holbrook, Jarita Charmian; Medupe, Rodney Thebe; Urama, Johnson O. (2008). African Cultural Astronomy: Current Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy Research in Africa. Springer. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4020-6639-9. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- Homerin, Th. Emil (2001-05-01). Umar ibn al-Fāriḍ. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-0528-1. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- Hurley, Frank; Ennis, Helen (2002-06-01). Man with a Camera: Frank Hurley Overseas. National Library Australia. ISBN 978-0-642-10737-4. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (9 February 2011). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-90245-5.

- Kerr, Ann Zwicker (1 November 2002). Painting the Middle East. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0752-6. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Kuban, Doğan (1974). Muslim Religious Architecture: Development of Religious Architecture in Later Periods. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-07084-4.

- Kuiper, Kathleen (11 December 2009). Islamic Art, Literature, and Culture. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-61530-097-6.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (22 August 2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- "Masjid al-Lu'lu'a". Archnet. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- O'Leary, De Lacy (26 July 2001). A Short History Of The Fatimid Khalifate. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24465-7.

- Petersen, Andrew (2002-03-11). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Robinson, Francis (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66993-1.

- Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2011-04-25). Islamic Art and Visual Culture: An Anthology of Sources. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-5401-7.

- Safran, Janina M. (2000). The Second Umayyad Caliphate: The Articulation of Caliphal Legitimacy in Al-Andalus. Harvard CMES. ISBN 978-0-932885-24-1. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Saifuddin, Ja'far us Sadiq Mufaddal (2002-12-01). Al Juyushi: A Vision of the Fatemiyeen. Graphico Printing Limited. ISBN 978-0-9539270-1-2. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Sanders, Paula (2004). "The Contest over Context: Fatimid Cairo in the Twentieth Century". Giorgio Levi Della Vida Conferences. Garnet & Ithaca Press. ISBN 978-0-86372-298-1. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- Sanders, Paula (2008). Creating Medieval Cairo: Empire, Religion, and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-Century Egypt. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-095-0. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- al Sayyad, Nezar (30 September 2011). Cairo. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06079-1.

- "The Art of the Fatimid Period (909–1171)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Tracy, James D. (2000-09-25). City Walls: The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Wijdan, Ali (1999). The arab contribution to islamic art: from the seventh to the fifteenth centuries. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-476-6. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Williams, Caroline (30 December 2008). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-205-3. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Yeomans, Richard (2006). The art and architecture of islamic cairo. Garnet & Ithaca Press. ISBN 978-1-85964-154-5. Retrieved 6 March 2013.