Fatal familial insomnia

| Fatal familial insomnia | |

|---|---|

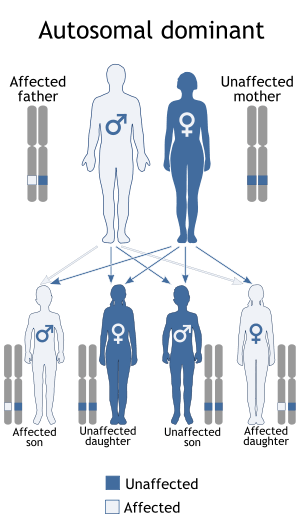

|

Autosomal dominant pattern | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Sleep medicine |

| ICD-10 | A81.9 |

| ICD-9-CM | 046.72 |

| OMIM | 600072 |

| DiseasesDB | 32177 |

| MeSH | D034062 |

Fatal familial insomnia (FFI) is an extremely rare autosomal dominant inherited prion disease of the brain. It is almost always caused by a mutation to the protein PrPC, but can also develop spontaneously in patients with a non-inherited mutation variant called sporadic fatal insomnia (sFI). FFI has no known cure and involves progressively worsening insomnia, which leads to hallucinations, delirium, confusional states like that of dementia, and eventually, death.[1] The average survival span for patients diagnosed with FFI after the onset of symptoms is 18 months.[1]

The mutated protein, called PrPSc, has been found in just 40 families worldwide, affecting about 100 people; if only one parent has the gene, the offspring have a 50% risk of inheriting it and developing the disease. With onset usually around middle age, it is essential that a potential patient be tested if they wish to avoid passing FFI on to their children. The first recorded case was an Italian man, who died in Venice in 1765.[2]

Presentation

The age of onset is variable, ranging from 18 to 60, with an average of 50. The disease can be detected prior to onset by genetic testing.[3] Death usually occurs between seven and 36 months from onset. The presentation of the disease varies considerably from person to person, even among patients from within the same family.

The disease has four stages:

- The person has increasing insomnia, resulting in panic attacks, paranoia, and phobias. This stage lasts for about four months.

- Hallucinations and panic attacks become noticeable, continuing for about five months.

- Complete inability to sleep is followed by rapid loss of weight. This lasts for about three months.

- Dementia, during which the patient becomes unresponsive or mute over the course of six months. This is the final progression of the disease, after which death follows.

Other symptoms include profuse sweating, pinpoint pupils, the sudden entrance into menopause for women and impotence for men, neck stiffness, and elevation of blood pressure and heart rate. Constipation is common as well. As the disease progresses, the patient is forever stuck in a state of pre-sleep limbo. During these stages, it is common for patients to repeatedly move their limbs as if dreaming.[4]

The first reported case in the Netherlands was of a 57-year-old man of Egyptian descent. The man came in with symptoms of double vision and progressive memory loss, and his family also noted he had recently become disoriented, paranoid, and confused. While he tended to fall asleep during random daily activities, he experienced vivid dreams and random muscular jerks during normal slow wave sleep. After four months of these symptoms, he started having convulsions in the hands, trunk, and lower limbs while awake. The patient died at 58 (seven months after the onset of symptoms). An autopsy was completed post-mortem which revealed mild atrophy of the frontal cortex and moderate atrophy of the thalamus. The atrophy of the thalamus is one of the most common signs of fatal familial insomnia.[5]

Effect on sleep

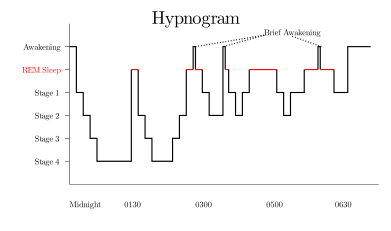

Normal sleep has different stages that together last 90 to 100 minutes:

- Non REM Stages 1 and 2: Light sleep NREM-sleep

- Non REM Stage 3 (previously 3 and 4): Deep slow wave sleep (SWS)

- REM-sleep when memorable dreams occur

FFI patients cannot go past stage 1 and thus their brains are not getting the rest they need to revive, as most reviving and repairing processes of the body are believed to happen during these deeper sleep stages.[6] For example, psychiatrist Ian Oswald observed that during slow wave sleep (SWS), the pituitary gland increases its secretion of growth hormones. This discovery led Oswald to conclude that SWS restores the wear and tear bodily tissues gain throughout the day.[7] Since a patient with FFI would be unable to reach SWS, and therefore the process of restoration during sleep, their body would become more worn each passing day.

Cause

Gene PRNP that provides instructions for making the prion protein PrPC is located on the short (p) arm of chromosome 20 at position p13.[8] Both FFI patients and those with familial Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (fCJD) carry a mutation at codon 178 of the prion protein gene. FFI is also invariably linked to the presence of the methionine codon at position 129 of the mutant allele, whereas fCJD is linked to the presence of the valine codon at that position.[9] "The disease is where there is a change of amino acid at position 178 when an asparagine (N) is found instead of the normal aspartic acid (D). This has to be accompanied with a methionine at position 129."[10]

Treatment

In late 1983, Italian neurologist/sleep expert Dr. Ignazio Roiter received a patient at the University of Bologna hospital's sleep institute. The man, known only as Silvano, decided in a rare moment of consciousness to be recorded for future studies and to donate his brain for research in hopes of finding a cure for future victims. As of 2016, no cure or treatment has yet been found for FFI. Gene therapy has been thus far unsuccessful. While it is not currently possible to reverse the underlying illness, there is some evidence that treatments that focus solely upon the symptoms may improve quality of life.[11]

It has been proven that sleeping pills and barbiturates are unhelpful; on the contrary, in 74% of cases, they have been shown to worsen the clinical manifestations and hasten the course of the disease.[12]

One of the most notable cases is that of Michael (Michel A.) Corke, a music teacher from New Lenox, Illinois (born in Watseka, Illinois). He began to have trouble sleeping before his 40th birthday in 1991; following these first signs of insomnia, his health and state of mind quickly deteriorated as his condition worsened. Eventually, sleep became completely unattainable, and he was soon admitted to University of Chicago Hospital with a misdiagnosis of clinical depression due to multiple sclerosis. Medical professionals Dr. Raymond Roos and Dr. Anthony Reder, at first unsure of the nature of his illness, initially diagnosed multiple sclerosis; in a bid to provide temporary relief in the later stages of the disease, physicians induced a coma with the use of sedatives, to no avail as his brain still failed to shut down completely. Corke died in 1993, a month after his 42nd birthday, by which time he had been completely sleep-deprived for six months.[13]

One person was able to exceed the average survival time by nearly one year with various strategies, including vitamin therapy and meditation, using different stimulants and hypnotics, and even complete sensory deprivation in an attempt to induce sleep at night and increase alertness during the day. He managed to write a book and drive hundreds of miles in this time but nonetheless, over the course of his trials, the person succumbed to the classic four-stage progression of the illness.[6][11]

In the late 2000s, a mouse model was made for FFI. These mice expressed a humanized version of the PrP protein that also contains the D178N FFI mutation.[14] These mice appear to have progressively fewer and shorter periods of uninterrupted sleep, damage in the thalamus, and early deaths, similar to humans with FFI.

As of 2016, studies suggest that doxycycline may be able to slow or even prevent the development of the disease.[15][16][17]

Epidemiology

It was reported in 1998 that there were 25 families in the world known to carry the gene for FFI: eight German, five Italian, four American, two French, two Australian, two British, one Japanese, and one Austrian.[18] In 2011, another family was added to the list when researchers found the first man in the Netherlands with FFI. While he had lived in the Netherlands for 19 years, he was of Egyptian descent.[5] There are other prion diseases that are similar to FFI and could be related but are missing the D178N gene mutation.[4]

Only nine cases of sporadic fatal insomnia have ever been diagnosed as of July 2005.[19] In sFI, there is no mutation in PRNP-prion gene in D178N, but all have methionine homozygosity at codon 129.[20][21]

Related conditions

There are other diseases involving the mammalian prion protein.[22] Some are transmissible (TSEs, including FFI) such as kuru, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, also known as "mad cow disease") in cows, and chronic wasting disease in American deer and American elk in some areas of the United States and Canada, as well as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD). Until recently, prion diseases were only thought to be transmissible via direct contact with infected tissue, such as from eating infected tissue, transfusion, or transplantation; new research now suggests that prion diseases can be transmitted via aerosols, but that the general public is not at risk of airborne infection.[23]

References

Notes

- 1 2 Schenkein J, Montagna P (2006). "Self management of fatal familial insomnia. Part 1: what is FFI?". MedGenMed. 8 (3): 65. PMC 1781306

. PMID 17406188.

. PMID 17406188. - ↑ The Family That Couldn't Sleep.

- ↑ Max, D.T. (May 2010). "The Secret of Sleep". National Geographic Magazine. p. 74.

- 1 2 Cortelli, Pietro; Gambetti, Pierluigi; Montagna, Pasquale & Lugaresi, Elio (1999). "Fatal familial insomnia: clinical features and molecular genetics". Journal of Sleep Research. 8: 23–29. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00005.x.

- 1 2 Jansen, C.; Parchi, P.; Jelles, B.; Gouw, A. A.; Beunders, G.; van Spaendonk, R. M. L.; van de Kamp, J. M.; Lemstra, A. W.; Capellari, S.; Rozemuller, A. J. M. (13 July 2011). "The first case of fatal familial insomnia (FFI) in the Netherlands: a patient from Egyptian descent with concurrent four repeat tau deposits". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 37 (5): 549–553. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01126.x. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- 1 2 Dying Without Sleep: Insomnia and its Implications

- ↑ Green, S. (2011). Sleep. In Green, S., Biological Rhythms, Sleep, and Hypnosis (65–6). England: Macmillan Publishers Limited.

- ↑ PRNP-gene

- ↑ PRPC gene mutation.

- ↑ About FFI in Perpetualsummer Archive.org

- 1 2 Schenkein J, Montagna P (2006). "Self-management of fatal familial insomnia. Part 2: case report". MedGenMed : Medscape general medicine. 8 (3): 66. PMC 1781276

. PMID 17406189.

. PMID 17406189. - ↑ Turner, Rebecca. "The Man Who Never Slept: Michael Corke". World Of Lucid Dreaming. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- ↑ health.howstuffworks.com

- ↑ Jackson W, et al. (2009). "Spontaneous Generation of Prion Infectivity in Fatal Familial Insomnia Knockin Mice". Neuron. 63 (4): 438–450. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.026. PMC 2775465

. PMID 19709627.

. PMID 19709627. - ↑ Forlonia, Gianluigi; Tettamantia, Mauro; Luccaa, Ugo; Albanesea, Yasmin; Quaglioa, Elena; Chiesaa, Roberto; Erbettab, Alessandra; Villanib, Flavio; Redaellib, Veronica; Tagliavinib, Fabrizio; Artusoc, Vladimiro; Roiterc, Ignazio (21 May 2015). "Preventive study in subjects at risk of fatal familial insomnia: Innovative approach to rare diseases". Prion. 9 (2): 75–79. doi:10.1080/19336896.2015.1027857. PMID 25996399.

- ↑ Robson, David (19 January 2016). "The tragic fate of the people who stop sleeping". BBC. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "Dying for sleep: Could there be a cure for Fatal Familial Insomnia?". ResearchGate. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ Gambetti and Lugaresi 1998

- ↑ Discovery-channel: "My Shocking Story-Dying to Sleep"

- ↑ Mehta LR, Huddleston BJ, Skalabrin EJ, et al. (July 2008). "Sporadic fatal insomnia masquerading as a paraneoplastic cerebellar syndrome". Arch. Neurol. 65 (7): 971–3. doi:10.1001/archneur.65.7.971. PMID 18625868.

- ↑ Moody KM, Schonberger LB, Maddox RA, Zou WQ, Cracco L, Cali I (2011). "Sporadic fatal insomnia in a young woman: a diagnostic challenge: case report". BMC Neurol. 11: 136. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-136. PMC 3214133

. PMID 22040318.

. PMID 22040318. - ↑ Panegyres, Peter; Burchell, Jennifer T. (2016). "Prion diseases: immunotargets and therapy". ImmunoTargets and Therapy: 57. doi:10.2147/ITT.S64795. ISSN 2253-1556.

- ↑ Mosher, Dave (January 13, 2011). "Airborne Prions Make for 100 Percent Lethal Whiff". Wired. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

Bibliography

- Akroush, Ann M. "Fatal Familial Insomnia". University of Michigan.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Fatal Familial Insomnia; FFI -600072

- Montagna P, Gambetti P, Cortelli P, Lugaresi E (2003). "Familial and sporadic fatal insomnia". Lancet Neurol. 2 (3): 167–76. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00323-5. PMID 12849238.

- Almer G, Hainfellner JA, Brücke T, et al. (1999). "Fatal familial insomnia: a new Austrian family". Brain. 122 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1093/brain/122.1.5. PMID 10050890.

External links

- "The Family that Couldn't Sleep" book by D.T. Max

- Schadler, Jay; Viddy, Laura. "Medical Mystery: When Sleep Doesn't Come, Death Does". ABC News.

- AFIFF Fatal Familial Insomnia Families Association website