Familial dysautonomia

| Familial dysautonomia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Facial features of a patient with familial dysautonomia over time. Note flattening of upper lip. By age 10 years prominence of lower jaw is apparent and by age 19 years there is mild erosion of right nostril due to inadvertent self-mutilation. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | neurology |

| ICD-10 | G90.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 742.8 |

| OMIM | 223900 |

| DiseasesDB | 11631 |

| MedlinePlus | 001387 |

| eMedicine | oph/678 |

| MeSH | D004402 |

| GeneReviews | |

Familial dysautonomia (FD), sometimes called Riley–Day syndrome[1] and hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type III (HSAN-III), is a disorder of the autonomic nervous system which affects the development and survival of sensory, sympathetic and some parasympathetic neurons in the autonomic and sensory nervous system resulting in variable symptoms, including insensitivity to pain, inability to produce tears, poor growth, and labile blood pressure (episodic hypertension and postural hypotension). People with FD have frequent vomiting crises, pneumonia, problems with speech and movement, difficulty swallowing, inappropriate perception of heat, pain, and taste, as well as unstable blood pressure and gastrointestinal dysmotility. FD does not affect intelligence. Originally reported by Conrad Milton Riley and Richard Lawrence Day in 1949,[2] FD is one example of a group of disorders known as hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies (HSAN).[3] All HSAN are characterized by widespread sensory dysfunction and variable autonomic dysfunction caused by incomplete development of sensory and autonomic neurons. The disorders are believed to be genetically distinct from each other.

Symptoms

The most distinctive clinical feature is absence of overflow tears with emotional crying after age 7 months. This symptom can manifest less dramatically as persistent bilateral eye irritation. There is also a high prevalence of breech presentation. Other symptoms include weak or absent suck and poor tone, poor suck and misdirected swallowing, and red blotching of skin.

Symptoms in an older child with familial dysautonomia might include:

- Delayed speech and walking

- Unsteady gait

- Spinal curvature

- Corneal abrasion

- Less perception in pain or temperature with nervous system.

- Poor growth

- Erratic or unstable blood pressure.

- Red puffy hands

- Dysautonomia crisis: constellation of symptoms response to physical and emotional stress; usually accompanied by vomiting, increased heart rate, increase in blood pressure, sweating, drooling, blotching of the skin and a negative change in personality.

Etiology

Familial dysautonomia is the result of mutations in IKBKAP gene on chromosome 9, which encodes for the IKAP protein (IkB kinase complex associated protein). There have been three mutations in IKBKAP identified in individuals with FD. The most common FD-causing mutation occurs in intron 20 of the donor gene. Conversion of T→C in intron 20 of the donor gene resulted in shift splicing that generates an IKAP transcript lacking exon 20. Translation of this mRNA results in a truncated protein lacking all of the amino acids encoded in exons 20-37. Another less common mutation is a G→C conversion resulting in one amino acid mutation in 696, where Proline substitutes normal Arginine. The decreased amount of functional IKAP protein in cells causes familial dysautonomia.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis of FD is supported by a constellation of criteria:

- No fungiform papillae on the tongue

- Decreased deep tendon reflexes

- Lack of an axon flare following intradermal histamine

- No overflow tears with emotional crying

Genetic testing

Genetic testing is performed on a small sample of blood from the tested individual. The DNA is examined with a designed probe specific to the known mutations. The accuracy of the test is above 99%. Dr. Anat Blumenfeld of the Hadasah Medical center in Jerusalem identified chromosome number 9 as the responsible chromosome.

Prenatal testing

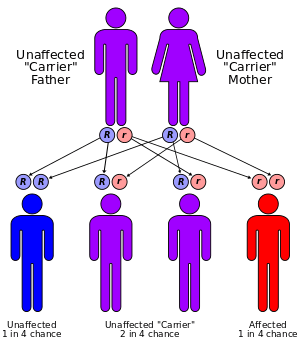

Familial dysautonomia is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means 2 copies of the gene in each cell are altered. If both parents are shown to be carriers by genetic testing, there is a 25% chance that the child will produce FD. Prenatal diagnosis for pregnancies at increased risk for FD by amniocentesis (for 14–17 weeks) or chorionic villus sampling (for 10–11 weeks) is possible.

Treatment and treatment locations

There currently is no cure for FD and death occurs in 50% of the affected individuals by age 30. There are only two treatment centers, one at New York University Hospital[4] and one at the Sheba Medical Center in Israel.[5] One is being planned for the San Francisco area.[6]

The survival rate and quality of life has increased since the mid 80s mostly due to greater understanding of the most dangerous symptoms. At present, FD patients can be expected to function independently if treatment is begun early and major disabilities avoided.

A major issue has been aspiration pneumonias, where food or regurgitated stomach content would be aspirated into the lungs causing infections. Fundoplications (by preventing regurgitation) and gastrostomy tubes (to provide non oral nutrition) have reduced the frequency of hospitalization.

Other issues which can be treated include FD crises, scoliosis, and various eye conditions due to limited or no tears.

An FD crisis is the body's loss of control of various autonomic nervous system functions including blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature. Both short term and chronic periodic high or low blood pressure have consequences and medication is used to stabilize blood pressure.

Treatment of manifestations

Although the FD-causing gene has been identified and it seems to have tissue specific expression, there is no definitive treatment at present. Treatment of FD remains preventative, symptomatic and supportive. FD does not express itself in a consistent manner. The type and severity of symptoms displayed vary among patients and even at different ages on the same patients. So patients should have specialized individual treatment plans. Medications are used to control vomiting, eye dryness, and blood pressure. There are some commonly needed treatments including:

- Artificial tears: using eye drops containing artificial tear solutions (methylcellulose)

- Feeding: Maintenance of adequate nutrition, avoidance of aspiration; thickened formula and different shaped nipples are used for baby.

- Daily chest physiotherapy (nebulization, bronchodilators, and postural drainage): for Chronic lung disease from recurrent aspiration pneumonia

- Special drug management of autonomic manifestations such as vomiting: intravenous or rectal diazepam (0.2 mg/kg q3h) and rectal chloral hydrate (30 mg/kg q6h)

- Protecting the child from injury (coping with decreased taste, temperature and pain perception)

- Combating orthostatic hypotension: hydration, leg exercise, frequent small meals, a high-salt diet, and drugs such as fludrocortisone.

- Treatment of orthopedic problems (tibial torsion and spinal curvature)

- Compensating for labile blood pressures

There is no cure for this genetic disorder.

Therapies under investigation

It is noted that in cell lines derived from heterozygous carriers of FD who display a normal phenotype, there are decreased levels of the wild-type IKAP transcript and also functional IKAP protein respectively. This would suggest that increasing the amount of the wild-type IKAP transcript may improve the manifestation in patients with FD.

Prognosis

The outlook for patients with FD depends on the particular diagnostic category. Patients with chronic, progressive, generalized dysautonomia in the setting of central nervous system degeneration have a generally poor long-term prognosis. Death can occur from pneumonia, acute respiratory failure, or sudden cardiopulmonary arrest in such patients.

Parents and patients should generally be educated regarding daily eye care and early warning signs of corneal problems as well as use of punctual cautery. This education has resulted in decreased corneal scarring and need for more aggressive surgical measures such as tarsorrhaphy, conjunctival flaps, and corneal transplants.

Epidemiology

Familial dysautonomia is seen almost exclusively in Ashkenazi Jews and is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. Both parents must be carriers in order for a child to be affected. The carrier frequency in Jewish individuals of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) ancestry is about 1/30, while the carrier frequency in non-Jewish individuals is unknown. If both parents are carriers, there is a one in four, or 25%, chance with each pregnancy for an affected child. Genetic counseling and genetic testing is recommended for families who may be carriers of familial dysautonomia.

Worldwide, there have been approximately 600 diagnoses recorded since discovery of the disease, with approximately 350 of them still living.[7]

Research

In January 2001, researchers at Fordham University and Massachusetts General Hospital simultaneously reported finding the genetic mutation that causes FD, a discovery that opens the door to many diagnostic and treatment possibilities.[8][9]

Despite that it probably would not happen in the near future, some expect that stem-cell therapy will result. Eventually, treatment could be given in utero.

While that may be years ahead, genetic screening became available around April 2001, enabling Ashkenazi Jews to find out if they are carriers. Screening organization Dor Yeshorim offers testing as part of its panel, which also includes Tay-Sachs disease and cystic fibrosis.

In the meantime more research into treatments are being funded by the foundations that exist. These foundations are organized and run by parents of those with FD. There is no governmental support beyond recognizing those diagnosed with FD as eligible for certain programs.[10]

See also

- Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy (HSAN)

- Congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis (CIPA), HSAN Type IV

- Congenital insensitivity to pain

- Dysautonomia

- Medical genetics of Ashkenazi Jews

References

- ↑ pediatriconcall.com

- ↑ Riley CM, Day RL, Greely D, Langford WS (1949). "Central autonomic dysfunction with defective lacrimation". Pediatrics. 3 (4): 468–77. PMID 18118947.

- ↑ Axelrod FB (2002). "Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies. Familial dysautonomia and other HSANs". Clin Auton Res. 12. Suppl 1 (7): I2–14. doi:10.1007/s102860200014. PMID 12102459.

- ↑ Dysautonomia Treatment and Evaluation Center

- ↑ Sheba Medical Center

- ↑ "San Francisco To Get a Genetics Center - Forward.com". Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ↑ http://www.familialdysautonomia.org/history.php

- ↑ Anderson SL, Coli R, Daly IW, Kichula EA, Rork MJ, Volpi SA, Ekstein J, Rubin BY (2001). "Familial dysautonomia is caused by mutations of the IKAP gene". Am J Hum Genet. 68 (3): 753–8. doi:10.1086/318808. PMC 1274486

. PMID 11179021.

. PMID 11179021. - ↑ Slaugenhaupt SA, Blumenfeld A, Gill SP, Leyne M, Mull J, Cuajungco MP, Liebert CB, Chadwick B, Idelson M, Reznik L, Robbins C, Makalowska I, Brownstein M, Krappmann D, Scheidereit C, Maayan C, Axelrod FB, Gusella JF (2001). "Tissue-specific expression of a splicing mutation in the IKBKAP gene causes familial dysautonomia". Am J Hum Genet. 68 (3): 598–605. doi:10.1086/318810. PMC 1274473

. PMID 11179008.

. PMID 11179008. - ↑ Benefits for people with FD - from Dysautonomia foundation

Further reading

- Axelrod FB, Hilz MJ (2003). "Inherited autonomic neuropathies". Semin Neurol. 23 (4): 381–90. doi:10.1055/s-2004-817722. PMID 15088259.

- Axelrod FB (2004). "Familial dysautonomia". Muscle Nerve. 29 (3): 352–63. doi:10.1002/mus.10499. PMID 14981733.

- Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF (2002). "Familial dysautonomia". Curr Opin Genet Dev. 12 (3): 307–11. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00303-9. PMID 12076674.

- Felicia B Axelrod; Gabrielle Gold-von Simson (October 3, 2007). "Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies: types II, III, and IV". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2 (39): 39. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-39. PMC 2098750

. PMID 17915006.

. PMID 17915006.