False killer whale

| False killer whale[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

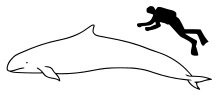

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Pseudorca Reinhardt, 1862 |

| Species: | P. crassidens |

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1846) | |

| | |

| False killer whale range | |

The false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) is a cetacean, and the third-largest member of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae). It lives in temperate and tropical waters throughout the world. As its name implies, the false killer whale shares characteristics, such as appearance, with the more widely known killer whale. Like the killer whale, the false killer whale attacks and kills other cetaceans, but the two species do not belong to the same genus. The false killer whale has not been extensively studied in the wild; much of the data about it have been derived by examining stranded false killer whales.[3]

Discovery

The false killer whale was first described by the British paleontologist and biologist Richard Owen in his 1846 book A history of British fossil mammals and birds.[4] He based this work on a fossil discovered in 1843 in the great fen at the neighourhood of Stamford, Lincolnshire. Owen proposed to name the cetacean Phocaena crassidens, and by comparing its characteristics and dimensions, noted a general resemblance to those of the grampus (Phocaena orca) and the round-headed porpoise (Phocaena melas).[4]

The species was thought extinct until Johannes Reinhardt confirmed it was alive when he described a large pod at the Kiel Bay in 1861. One of these was captured, and others were found the following year, beached on the coast of Denmark.[5]

Population and distribution

The false killer whale appears to have a widespread, if small, presence in tropical and semitropical oceanic waters. A few of these whales have been found in temperate water, but these are probably stray individuals. Their most common habitat is the open ocean, though they also frequent other areas.[6] They have been sighted in fairly shallow waters such as the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea, as well as the Atlantic Ocean (from Scotland to Argentina), the Indian Ocean (in coastal regions and around the Lakshadweep Islands), the Pacific Ocean (from the Sea of Japan to New Zealand and the tropical area of the eastern side), and in Hawaii. Recently, a pod of false killer whales was observed hunting down a small species of shark in Australia.[7]

The Hawaiian populations are the most studied groups of false killer whales. The three distinct groups in the islands are an offshore population, a northwestern Hawaiian Island group, and a small group around the main Hawaiian Islands. This last group, a unique, small, insular population, is genetically distinct from the other populations.[8]

A false killer whale and a bottlenose dolphin mated in captivity and produced a fertile calf.[9] The hybrid offspring has been called a “wholphin”.

Description

The false killer whale is black with a grey throat and neck. It has a slender body with an elongated, tapered head and 44 teeth. The dorsal fin is sickle-shaped and its flippers are narrow, short, and pointed. The average size is around 4.9 m (16 ft). Females can reach a maximum known size of 5.1 m (17 ft) in length and 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) in weight, while the largest males can reach 6.1 m (20 ft) and as much as 2,200 kg (4,900 lb).[6][10][11]

Human interaction

False killer whales are kept in captivity and studied in the wild by scientists. Several public aquaria display them. For example, Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium in Japan displays false killer whales in the Okichan Theater.[12]

These whales have been known to approach and offer fish they have caught to humans diving or boating.[6][8]

Scientists have undertaken research to understand more about the species—including population surveys, satellite-tagged individual whales, and carcasses studies. From these studies, they determined information about habitat, range, and distinct populations. Recent study of the local population of false killer whales in Hawaii shows evidence of a dramatic decline over the last 20 years. Five years of aerial surveys from 1993 through 2003 show a steep decline in sighting rates. Group sizes of the largest groups documented before 1989 surveys were almost four times larger than the entire 2009 population estimate.[8]

Beachings

On 30 July 1986, a pod of 114 false killer whales became stranded at Town Beach, Augusta, in Flinders Bay, Western Australia. In a three-day operation, coordinated by the Department of Conservation and Land Management, volunteers carried 96 of the whales on trucks to more sheltered waters, and then successfully guided them out into the bay.[13][14]

On 2 June 2005, up to 140 (estimates vary) false killer whales were beached at Geographe Bay, Western Australia.[15] The main pod, which had split into four strandings along the length of the coast, was successfully moved back to sea, with only one death, after 1,500 volunteers intervened, coordinated once again by the Department of Conservation and Land Management.

Just before sunrise on 30 May 2009, a pod of 55 false killer whales was discovered stranded on a sandy beach at Kommetjie in South Africa (34°8′3.98″S 18°19′58.22″E / 34.1344389°S 18.3328389°E).[16] Despite the efforts of over 50 volunteers, most animals beached themselves again and the weather complicated further attempts.[17] Authorities euthanized 44 whales.

As of July 2014, no record of an orphaned infant of the species surviving to adulthood after stranding has been reported, but veterinarians expressed hope about the prospects of a six-week-old male calf found on the shores of North Chesterman beach, near Tofino, British Columbia.[18] He was found in critical condition on 11 July 2014, and received care at the Vancouver Aquarium.[18][19]

Conservation

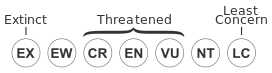

The false killer whale is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS), and the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS). The species is further included in the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manate and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU) and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU).

In November 2012, the United States' National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recognized the Hawaiian population of false killer whales, which numbers around 150 individuals, as endangered.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Mead, J.G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Taylor, B.L.; Baird, R.; Barlow, J.; Dawson, S.M.; Ford, J.; Mead, J.G.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Wade, P. & Pitman, R.L. (2008). "Pseudorca crassidens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ↑ Barid, R. W. (2002). False killer whale. Encyclopedia of marine mammals. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 411–412.

- 1 2 Owen, R. (1846). A history of British fossil mammals and birds. pp. 516–520.

- ↑ Matthews, L. Harrison (1977). La Vida de los Mamíferos, Tomo II (in Spanish). Historia Natural Destino, vol. 17. Barcelona, España: Ediciones Destino. p. 844. ISBN 84-233-0700-X.

- 1 2 3 "False killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens)". ARKive. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ Mazza, Ed. "Incredible Drone Video Shows False Killer Whales Hunt, Kill And Eat A Shark". Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Hawai‘i's false killer whales". Cascadia Research.

- ↑ "Whale-dolphin hybrid has baby wholphin". MSNBC. 15 April 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ↑ "False killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens)". Marine Species Identification Portal. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "False Killer Whale". SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "Okichan Theater". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "Whale rescue in 1986 changed not just the people who were there". ABC. South West WA. 7 June 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ↑ "World watched as WA town saved the whales". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ↑ "Scores of whales stranded in western Australia". The Daily Telegraph. London. 23 March 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Pitney, Nico (30 May 2009). "Whales Killed At Kommetjie In South Africa (VIDEO)". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ↑ ""Fifty Pilot Whales Beach Themselves in Kommetjie". 1 June 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- 1 2 Carmichael, Jackie (24 July 2014). "Rescued Pseudorca clings to life, shows some progress". Alberni Valley Times.

- ↑ O'Connor, Elaine (25 July 2014). "Critically ill false killer whale calf improving at Vancouver Aquarium's marine rescue centre". The Province.

- ↑ Kearn, Rebekah (27 November 2012). "Hawaiian False Killer Whale Endangered". Courthouse News. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

Further reading

- Heptner, V. G.; Nasimovich, A. A; Bannikov, Andrei Grigorevich; Hoffmann, Robert S, Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, part 3 (1996). Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation

- National Audubon Society: Guide to Marine Mammals of the World ISBN 0-375-41141-0

- Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- "Beached whales saved in Australia". BBC News. June 2005. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

External links

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

- NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Resources, False Killer Whale (Pseudorca crassidens)

- Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas

- Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area

- Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia

- Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region

- Voices in the Sea - Sounds of the False Killer Whale