Fakiha

-

fakiha

-

fakiha

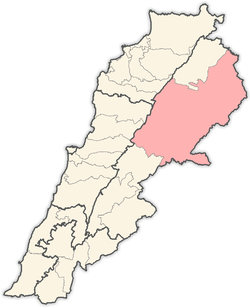

Bearing a name appropriate to the usage of a significant amount of its land, the village of Al-Fakiha (Arabic: فاكهة) (literally "fruits") lies in the North-East section of the Bekaa Valley Governorate in Lebanon. The village itself is separated into three neighborhoods: Jdaydi, Zaytoun and Fakiha, the grouping adopting the name of the third one.

Fakiha neighbourhood

The Fakiha sub-village is mostly suburbia with houses built very close to each other if not on top of each other or connected in some other way. As a result, a close-knit community has developed in the village, despite two major religions being present: Sunnite Muslim and Melkite Greek Catholic Church. The authentic families in Fakiha zaytoun and jdeideh like bayt Al Sheikh-Ali mainly , Mrad, Kibar, succarieh, eit and Khalil as they are the most predominant families in the three suburbs. The village is mainly Sunni.[1]

Zaytoun

Zaytoun (literally "olives") is a much more spaced section. The houses are built more modernly and spaciously, each boasting a large block of land (at least two to three acres). The land is used to its full potential, with the agriculture including an abundance of olive groves, orchards of apricot and fig trees as well as a variety of other fruits and vegetables depending on the whim of the farmer and his intention of use of the crops.

Within Zaytoun is a branch of the Omar El-Mokhtar educational facilities called Al-Qayrawaan. It is one of the few in the area that supports a K-9 English/Arabic curriculum with highly qualified staff. The sciences, mathematics and a language subject is taught in English, whereas the humanities and a language subject are taught in Arabic. Moreover, extra-curriculum subjects are available. The community present in Zaytoun shares the closeness of that of Fakiha despite the more spaced housing. However, its population is completely of the Sunni Muslim faith.

-

jdeide

-

jdeide

Jdeide or al jdeideh

The last of the three sections is the Jdaydi sub-village. It is similar in structure to Zaytoun, but the difference is that the housing is less spacious as is the land allotments. The community in Jdaydi is not as close-knit as the former two, with the tendency to form social groups more noticeable, especially among the youth. The population is a mixture of Sunni Muslim and the Catholic church. Jdeide or Djedeideh is very famous in the second world war as Djedeide Fortress or Djedeideh Gorge ^^The defence was to be based on a number of ‘fortresses’, corresponding more or less to the desert ‘boxes’, covering all the routes down through Syria. The Division's particular responsibility, the Djedeide fortress, was an important one, blocking the Bekaa valley, for centuries a north-south highway pointing at Palestine and Egypt. Near the little village of Djedeide the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges bounding this valley converged, making a naturally strong position that would be difficult to get at from a flank. The fortress was to be tank-proof, dug for all-round defence, and stocked with two months' supplies. All this was to be done by mid-May—Jerry, said the experts, would not be able to overcome all the obstacles separating him from Syria before the end of May at the earliest. ^The Djedeide fortress, sprawling across the valley and up the hills on either side, had already had some work done on it— an anti-tank ditch across the front was nearly finished. Fourth Brigade had the right-hand sector, consisting mostly of the forbidding Anti-Lebanon slopes; only 18 Battalion had a stretch of comparatively low, accessible ground. About a mile along the good main road running north from camp the unit's area began, and from there it stretched another mile and a half forward, astride the road, as far as Djedeide village, which was included in the front line. The battalion's mile and a quarter of front was to be held by two companies, B in Djedeide and on the valley floor to the left of the road, D among gardens and orchards on gentle slopes on the right flank, just above Djedeide. The rest of the unit was farther back, perched on hillsides on the right of the road, in the lee of a rocky spur which came down just behind Djedeide. The battalion's right-hand neighbour, 20 Battalion, looked down on it from the crags, while 18 Battalion itself looked down on the valley to its left, where other troops were later to come in and complete the line.

For two months the men worked at Djedeide, blasting away the hard rock, hewing out slit trenches and gun positions, living quarters and first-aid posts, observation posts and headquarters, the last-named roofed over and strengthened with heavy railway iron. Some natural caves provided ready-made dugouts without the hard work, once the traces of native occupation were cleared away. Everything was camouflaged, and an intricate system of dummy and alternative positions was built. The Syrians living nearby became very friendly after a while, and the first-aid posts found themselves acting fairy godmothers to the villagers, whose medical services seemed to be nil.

At first the men attacked the work with enjoyment. It was a novelty to be in cultivated country, or even on a rocky hill, after the eternal sand and sameness of Egypt. The air was crisp and clear, the cold invigorating, and the weather for the first few days good. From about 18 to 25 March the retreating winter had a last fling, with vicious rainstorms, snow almost page 241 to the bottom of the hills, and freezing cold; but this ended very quickly, and by the end of the month the sun was out again and the valley warming up with the advance of spring. The oranges ripened and were a pleasant variation in the rations, succeeded by apricots as the weeks wore on.

The malarial season came too. The Bekaa valley is a highly malarious area, and from 4 April every possible weapon was turned against its bearer, the too friendly anopheles mosquito. Anti-malaria squads could be seen prowling the area spraying stagnant water with insecticide. Complicated personal precautions appeared in routine orders—mosquito nets to be tucked in round blankets at dusk, sleeping quarters sprayed every morning, face nets and gloves for sentries, repellent cream smeared on exposed skin. You even saw inspecting officers running their fingers along a man's cheek to see if he had greased himself properly. Later in April, when summer clothes were issued, the unlovely Bombay bloomers at last came into their own, being unhitched and let down below the knee at dusk to dissuade the ‘mossies’. In 18 Battalion, as in every other unit, the men were apt to look on all these precautions with a tolerant contempt, and observe them when convenient. But this was not the case with typhus, which was reported in the Bekaa valley in March. This most unpleasant disease commanded more respect among the Kiwis, who were quite ready to co-operate by obeying ‘out of bounds’ restrictions where typhus was concerned.

As the weeks went on and the heat increased, the first enthusiasm for manual labour was less evident. The Bekaa valley, the men found, was a natural wind funnel. It blew almost continuously, sometimes in gales that forced fine dust in everywhere—you might as well be back in Egypt, was the men's reaction whenever this got particularly bad. The tempo of the work slackened considerably.

With the receding snow the mountains lost their beauty and became arid, ragged hunks of rock, and though the valley blossomed in lush spring green splashed with the vivid red of wild poppies, there was a feeling of being shut in, of having no horizon wider than the few miles of river plain and the mountain tops. This increased when in late April the semi-nomadic local peasants began their move to summer grazing page 242 grounds. Every day and all day the valley was filled with a moving throng of sheep and camels, of dark gipsy-looking people, of donkeys loaded high with household goods, all coming from nobody knew where and disappearing into the vague distance. No wonder that the Kiwis, without enough hard work to absorb all their surplus energy, tended to become restless.

With restlessness comes mischief. Mild mischief, to be sure, but it took several forms—a vastly greater consumption of questionable liquor with all its unpleasant effects, an equally vast increase in the popularity of that expensive sport ‘two up’, systematic dynamiting of the fish out of the Orontes River which ran past 18 Battalion's camp some two miles away.

This last caused most trouble. Beginning in a small way in March, it had assumed such proportions by late April that the river was practically denuded of fish, and the local authorities, perturbed by the disappearance of one of their staple food sources, made a vigorous protest which led to the sport being completely banned under penalty of severe punishment.

It was all very well putting notices in routine orders banning this or that, but it was more to the point to provide recreation. So this is what 18 Battalion set out to do, and it was very successful. ^ from ^^ The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945^^

Emigration

Being in direct contact with the major road that connects Lebanon to Syria and, in turn, to the rest of the Arab world, Fakiha has flourished commercially and culturally and is a major contributor in the field of teaching across the entire Bekaa Valley. Not only have its inhabitants spread across the country, but a significant amount of them have emigrated to many countries including Brazil, Australia, the America, Canada, France, Italy, Argentina and other countries all over the world.

References

- ↑ , p.6.

External links

- Fekeheh, Localiban

Coordinates: 34°14′44″N 36°24′21″E / 34.24556°N 36.40583°E