Euston railway station

| Euston | |

|---|---|

| London Euston | |

|

Main entrance in 2009 | |

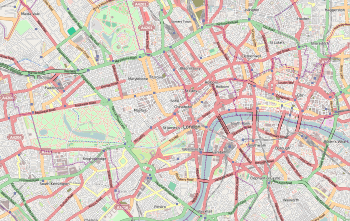

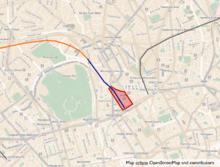

Euston Location of Euston in Central London | |

| Location | Euston Road |

| Local authority | London Borough of Camden |

| Managed by | Network Rail |

| Station code | EUS |

| DfT category | A |

| Number of platforms | 18 |

| Accessible | Yes [1] |

| Fare zone | 1 |

| OSI |

Euston tube station Euston Square St Pancras King's Cross |

| Cycle parking | Yes – platforms 17–18 and external |

| Toilet facilities | Yes |

| National Rail annual entry and exit | |

| 2010–11 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2011–12 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2012–13 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2013–14 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| 2014–15 |

|

| – interchange |

|

| Railway companies | |

| Original company | London & Birmingham Railway |

| Pre-grouping | London & North Western Railway |

| Post-grouping | London Midland & Scottish Railway |

| Key dates | |

| 20 July 1837 | Opened |

| 1849 | Expanded |

| 1962–1968 | Rebuilt |

| Other information | |

| Lists of stations | |

| External links | |

| WGS84 | 51°31′42″N 0°07′59″W / 51.5284°N 0.1331°WCoordinates: 51°31′42″N 0°07′59″W / 51.5284°N 0.1331°W |

|

| |

Euston railway station or London Euston /ˈlʌndən.ˈjuːstən/ is a central London railway terminus and one of 19 stations managed by Network Rail.[4] It is the sixth busiest railway station in the UK.

Euston is the southern terminus of the West Coast Main Line, the busiest intercity passenger route in Britain and the main gateway from London to the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and parts of Scotland. Virgin Trains provides high-speed intercity services to these regions. Its most important long-distance destinations are Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow. London Midland also provide local commuter and regional services via the WCML from London to Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire as well as long-distance services to the West Midlands county, Staffordshire and Cheshire. Euston is also the terminus for suburban services on the Watford DC Line operated by London Overground.

It is connected to Euston tube station and near to Euston Square tube station on the London Underground. It is a short walk from King's Cross Station, the southern terminus of the East Coast Main Line, and St Pancras International Station for the Midland Main Line and for Eurostar to France, Belgium and the Netherlands. These stations are all in Travelcard Zone 1.

History

Euston was the first intercity railway station in London, opened on 20 July 1837 as the terminus of the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR).[5] The building was demolished in the 1960s and replaced with the present building in the international modern style.

The site was chosen in the early 1830s by George and Robert Stephenson, engineers of the L&BR. The area was mostly farmland at the edge of the expanding city. The station was named after Euston Hall in Suffolk, the ancestral home of the Dukes of Grafton, the main landowners in the area. Objections by local farmers meant that, when the Act authorising construction of the line was passed in 1833, the terminus was at Chalk Farm. These objections were overcome, and in 1835 an Act authorised construction of the station, which then went ahead.[5][6]

The station and railway have been owned by the L&BR (1837–1845), the London and North Western Railway (1846–1922), the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (1923–1947), British Railways (1948–1994), Railtrack (1994–2001) and Network Rail (2001–present)

Original building

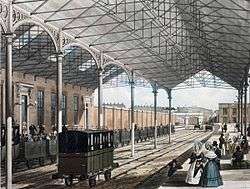

The original station was built by William Cubitt.[7] It was designed by the classically trained architect Philip Hardwick[8][9] with a 200 ft (61 m)-long trainshed by structural engineer Charles Fox. It had two platforms, one for departures and one for arrivals. Also by Hardwick was a 72 ft (22 m)-high Doric propylaeum, the largest ever built,[10] erected at the entrance as a portico, known as the Euston Arch.

.jpg)

Until 1844 trains were pulled up the incline to Camden Town by cables because the L&BR's Act of Parliament prohibited the use of locomotives in the Euston area; this is said to have been in response to concerns of local residents about noise and smoke from locomotives toiling up the incline.[11]

The station grew rapidly as traffic increased. It was greatly expanded with the opening in 1849 of the Great Hall, designed by Hardwick's son Philip Charles Hardwick in classical style. It was 126 ft (38 m) long, 61 ft (19 m) wide and 64 ft (20 m) high, with a coffered ceiling and a sweeping double flight of stairs leading to offices at its northern end. Architectural sculptor John Thomas contributed eight allegorical statues representing the cities served by the line. The station stood on Drummond Street, further back from Euston Road than the front of the modern complex; Drummond Street now terminates at the side of the station but then ran across its front.[12] A short road called Euston Grove ran from Euston Square towards the arch. Two hotels, the Euston Hotel and the Victoria Hotel, flanked the northern half of this approach.

As traffic grew, the station required further expansion. Two platforms were added in the 1870s with new service roads and entrances, and four in the 1890s, bringing the total to 15.[5] The growth of the platforms took place as follows:

- Nos 1/2 (built 1873)

- No 3 (1837, the original arrival platform)

- Nos 4/5 (1891)

- No 6 (1837, the original departure platform)

- Nos 7/8 (two short platforms that were rarely used)

- Nos 9/10 (1840, mostly used for parcels)

- No 11 (mainly used for parcels)

- Nos 12–15 (1892, used for main line services and accessed from a separate entrance termed the West Station).[13]

Apart from the lodges on Euston Road and statues now on the forecourt, few relics of the old station survive. The National Railway Museum's collection at York includes a commemorative plaque and Edward Hodges Baily's statue of George Stephenson, both from the Great Hall; the entrance gates; and an 1846 turntable discovered during demolition.

-

The Great Hall

-

Euston Arch (ca 1851)

-

LNWR War Memorial by Reginald Wynn Owen

-

LNWR Portland stone entrance lodge

-

Trains at Euston in 1944.

1930s rebuilding proposals

By the 1930s Euston had become congested, and the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) considered rebuilding it. In 1931 it was reported that a site for a new station was being sought, with the most likely option being behind the existing station in the direction of Camden Town.[14] By 1937 it had appointed the architect Percy Thomas to produce designs.[15] He proposed a new American-inspired station that would involve removing or re-siting the arch. When World War II intervened, the proposals were shelved.[16]

New building

In the early 1960s it was decided that a larger station was required. Because of the restricted layout of track and tunnels at the northern end, enlargement could be accomplished only by expanding southwards over the area occupied by the Great Hall and the Arch.[6] Amid much public outcry, the station building and the Arch were demolished in 1961–2 and replaced by a new building. Its opening in 1968 followed the electrification of the West Coast Main Line, and the new structure was intended to symbolise the coming of the "electric age". The station was built by Taylor Woodrow Construction Ltd[6] to a design by BR's architects in consultation with Richard Seifert & Partners, responsible for the second phase of the complex in the late 1970s.

The station is a long, low structure with a frontage of some 197 m (646 ft). The second phase consists of a bus terminal and three low-rise office towers overlooking Melton Street and Eversholt Street. The offices were occupied by British Rail, then by Railtrack, and finally by Network Rail, which has now vacated all but a small portion of one of the towers. These buildings are in a functional style; the main facing material is polished dark stone, complemented by white tiles, exposed concrete and plain glazing. The station has a single large concourse, separate from the train shed. A few remnants of the older station remain: two Portland stone entrance lodges and a war memorial. A statue of Robert Stephenson by Carlo Marochetti, previously in the old ticket hall, stands in the forecourt.

There is a large statue by Eduardo Paolozzi named Piscator dedicated to German theatre director Erwin Piscator at the front of the courtyard. Other pieces of public art, including low stone benches by Paul de Monchaux around the courtyard, were commissioned by Network Rail in the 1990s.

The station has catering units and shops, a large ticket hall and an enclosed car park with over 200 spaces.[17]

The screening-off and positioning of platforms away from a spacious main concourse results in a waiting area protected from the elements, while areas in front of the intercity platforms allow passengers to queue without obstructing passenger flow in the main body of the station. Passenger flow is further aided by the positioning of the main departure indicator board to encourage passengers to gather away from platform entrances, and by a walkway under the main concourse that provides a direct link from commuter platforms 8 to 11 to the Underground station.

The lack of daylight on the platforms compares unfavourably with the glazed trainshed roofs of traditional Victorian railway stations, but the use of the space above as a parcels depot[18] released the maximum space at ground level for platforms and passenger facilities.

The station has 18 platforms: platforms 8 to 11 are used for London Overground and London Midland commuter and regional services, and have automatic ticket gates. Platforms 1, 2, 14 and 15 are extra long to accommodate the 16-car Caledonian Sleeper.

-

Euston station and associated offices

-

Station signage

-

The trainshed from above

Architectural controversy

Euston's 1960s style of architecture has been described as "hideous",[19] "a dingy, grey, horizontal nothingness"[20] and a reflection of "the tawdry glamour of its time", entirely lacking in "the sense of occasion, of adventure, that the great Victorian termini gave to the traveller".[21] Writing in The Times, Richard Morrison stated that "even by the bleak standards of Sixties architecture, Euston is one of the nastiest concrete boxes in London: devoid of any decorative merit; seemingly concocted to induce maximum angst among passengers; and a blight on surrounding streets. The design should never have left the drawing-board – if, indeed, it was ever on a drawing-board. It gives the impression of having been scribbled on the back of a soiled paper bag by a thuggish android with a grudge against humanity and a vampiric loathing of sunlight".[22] Michael Palin, explorer and travel writer, in his contribution to Great Railway Journeys titled "Confessions of a Trainspotter", likened it to "a great bath, full of smooth, slippery surfaces where people can be sloshed about efficiently".[23]

Access to parts of the station is difficult for people with physical disability. The ramps from the concourse down to platform level are too steep for unassisted wheelchairs, but the introduction of lifts in May 2010 made the taxi rank and underground station accessible from the concourse.

The demolition of the original buildings in 1962 has been described as "one of the greatest acts of Post-War architectural vandalism in Britain" and is believed to have been approved by the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, the first of a line of Prime Ministers who championed motorway building. The replacement trainshed has a low, flat roof, making no attempt to match the airy style of London's major 19th century trainsheds. The attempts made to preserve the earlier building, championed by the later Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman, led to the formation of the Victorian Society and heralded the modern conservation movement.[24] This movement saved the nearby high Gothic St Pancras Station when threatened with demolition in 1966, ultimately leading to its renovation in 2007 as the terminus of HS1 to the Continent.

The demolition of the original building is often compared to the 1963 demolition of New York Penn Station, which similarly alerted preservationists in New York City to the importance of saving historic buildings.

1966 Asquith Xavier overturns colour bar

Up until 1966 Euston Station, along with St Pancras Station nearby, operated a colour bar, a ban on people of colour from working on the trains, operated by the unions and the management of the station despite the passing of the Race Relations Act in 1965 which made discrimination on the grounds of colour illegal in public places. The Act stated that it was against the law to "refuse anyone access, on racial grounds, to public places such as hotels, pubs, restaurants, cinemas, public transport or any place run by a public authority". But the legislation did not apply to the workplace. Asquith Xavier went public about his desire to work as a train guard and caused uproar particularly among his fellow workers. But as a result of his bravery the Race Relations Act was strengthened to include the workplace in its provisions. [25]

1973 IRA attack

Extensive but superficial damage was caused by an IRA bomb that exploded close to a snack bar at approximately 1:10 pm on 10 September 1973, injuring eight people.[26] The Metropolitan Police had received a three-minute warning and were unable to evacuate the station completely, but British Transport Police evacuated much of the area just before the explosion, reducing casualties. In 1974, the mentally-ill Judith Ward confessed to the bombing and was convicted of this and other crimes despite the evidence against her being highly suspect and Ward retracting her confessions. She was acquitted in 1992, and the actual culprit has not been found.[27]

Privatisation

Ownership of the station transferred from British Rail to Railtrack plc in 1994, passing to Network Rail in 2002 following the collapse of Railtrack.

In 2005 Network Rail was reported to have long-term aspirations to redevelop the station, removing the 1960s buildings and providing more commercial space by using the "air rights" above the platforms.

In December 2005 Network Rail announced plans to create a subway link to Euston Square tube station, currently separated by a five-minute walk along Euston Road.[28]

2007 rebuilding announcement

On 5 April 2007, British Land announced that it had won the tender to demolish and rebuild the station, spending some £250m of its overall redevelopment budget of £1bn for the area. The number of platforms would increase from 18 to 21.[29] Media reports in early 2008 hinted that the Arch could be rebuilt.[30]

Sydney & London Properties, project manager to the Euston Estate Limited Partnership, launched a Vision Masterplan in May 2008 with the aim of stimulating debate about the future of the station and its neighbourhood.[31]

2011 redesign announcement

In September 2011 plans for demolition were cancelled, and Aedas was appointed to give the station a makeover.[32]

Matthew Flinders bicentenary

In July 2014 a statue of Matthew Flinders, who circumnavigated the globe and charted Australia, was unveiled; it is thought that his grave lies under platform 15 at the station.[33]

Current status

Usage

Euston is the sixth-busiest terminus in London by entries and exits.[34][35][36][37]

High Speed 2

On 11 March 2010 the Secretary of State for Transport announced that Euston was the preferred southern terminus of the proposed High Speed 2 line to Birmingham and the north.[38] This would require expansion to the south and west to create new sufficiently long platforms. These plans would preclude the 2007 reconstruction and would entail complete reconstruction, involving the demolition of 220 Camden Council flats, with half the station providing conventional train services and the new half high-speed trains. The Command Paper suggests rebuilding the Arch, and an artist's impression includes it.[39]

The station would have 24 platforms serving both high-speed and classic lines. These would be at a low level. The flats demolished for the extension would be replaced by significant building work above. The underground station would be rebuilt and connected to Euston Square tube station. When High Speed 2 is extended beyond Birmingham, the Mayor's office believes it will be necessary to build the proposed Crossrail 2 line via Euston to relieve 10,000 extra passengers forecast to arrive during an average day.[40][41][42][43]

To relieve pressure on Euston during and after rebuilding for High Speed 2, HS2 Ltd has proposed the diversion to Old Oak Common (for Crossrail) of eight London Midland trains per hour originating/terminating between Tring and Milton Keynes Central (inclusive).[44]

Accidents and incidents

- On 26 April 1924, an electric multiple unit was in a rear-end collision with an excursion train.[45]

- On 27 August 1928, a passenger train crashed through the buffers. Thirty people were injured.[46]

- On 10 September 1973, a snack bar at the station was bombed by the Provisional IRA, injuring eight people.[47]

National Rail

There are four train operating companies from Euston:

Virgin Trains operates Intercity West Coast services from platforms 1–7 and 12–18:

- 1 train per hour to Glasgow Central / Edinburgh Waverley (alternating) via Birmingham.

- 1 to Glasgow Central via Preston. Additional services operate to/from Preston, Lancaster, Carlisle during peak times.

- 2 to Birmingham New Street via Coventry, extended to/from Wolverhampton (at peak hours)

- 3 to Manchester Piccadilly via Stockport;

- 2 via Stoke-on-Trent

- 1 via Crewe,

- 1 to Liverpool Lime Street via Stafford, Crewe and Runcorn.

- 1 to Chester via Crewe, with certain trains extended along the North Wales Coast Line to Bangor or Holyhead for the ferries to Ireland, such as Irish Ferries as well as Stena Line to Dublin Port, one train on Mon-Fri to Wrexham General

- 2 trains per day to Shrewsbury

- 1 train per day on Monday-Friday to Blackpool North

London Midland operates regional and commuter services from platforms 8, 9, 10 and 11. Outer suburban services depart from platforms 7, 12–15 and 17–18.

- 2 trains per hour to Tring

- 1 to Milton Keynes Central

- 2 to Birmingham New Street via Northampton

- 1 to Northampton.

- 1 to Crewe via Stafford and Stoke-on-Trent

London Overground operates local commuter services, from platform 9, with a few departing from platforms 8, 10 and 11.

- 3 trains per hour to Watford Junction via the Watford DC Line.

Caledonian Sleeper operates two nightly services to Scotland, from platforms 1 & 2.

- Highland sleeper to Aberdeen via Kirkcaldy and Dundee, Fort William via Dalmuir, and Inverness via Stirling and Perth.

- Lowland sleeper to Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Waverley via Carlisle.

London Underground

Euston station is directly above and connected to Euston tube station, on the Victoria line and the Northern line (both Bank and Charing Cross branches) of the London Underground. Euston Square tube station on the Circle line, Hammersmith & City line and Metropolitan line is a five-minute walk away along Euston Road.

If High Speed 2 goes ahead, Transport for London (TfL) plans to change the safeguarded route for the proposed Chelsea–Hackney line to include Euston between Tottenham Court Road and King's Cross St Pancras.[48] As part of the rebuilding work for High Speed 2, it is proposed to integrate Euston and Euston Square into a single tube station.[41]

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

towards Hammersmith | Circle line Transfer at: Euston Square | |||

| Hammersmith & City line Transfer at: Euston Square | towards Barking |

|||

| Metropolitan line Transfer at: Euston Square | towards Aldgate |

|||

| Northern line Charing Cross branch Transfer at: Euston | ||||

| Northern line Bank branch Transfer at: Euston | ||||

towards Brixton | Victoria line Transfer at: Euston | towards Walthamstow Central |

Bus Station

There is a bus station directly in front of the station for bus services to many parts of London.

See also

- Curzon Street railway station – the Birmingham counterpart of the original Euston

- Pennsylvania Station (New York City) – a station similarly demolished and replaced

- Crossrail 3 – an unofficially proposed rail tunnel under London between Euston and Waterloo, providing a through route across the city.

References

- ↑ "London and South East" (PDF). National Rail Enquiries. National Rail. September 2006. Archived from the original (pdf) on 6 March 2009.

- ↑ "Out of Station Interchanges" (XLS). Transport for London. May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Station usage estimates". Rail statistics. Office of Rail Regulation. Please note: Some methodology may vary year on year.

- ↑ "Commercial information". Our Stations. London: Network Rail. April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Euston Station, London". Network Rail. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 The New Euston Station 1968. British Rail information booklet.

- ↑ Holland & Hannen and Cubitts – The Inception and Development of a Great Building Firm, 1920, p. 41.

- ↑ www.shaw-hardwick.co.uk – Website in memory of the Hardwick architects

- ↑ Cole, Beverly (2011). Trains. Potsdam, Germany: H.F.Ullmann. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-8480-0516-1.

- ↑ "Arch outside the main entrance to Euston Station, Camden, London, 1952". Museum of London Picture Library. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- ↑ "London and Birmingham Railway". Camden Railway Heritage Trust. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ www.motco.com – 1862 map, showing position of 1849 station.

- ↑ McCarthy, Colin; McCarthy, David (2009). Railways of Britain – London North of the Thames. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7110-3346-7.

- ↑ "New Euston Station". Western Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 30 January 1931. Retrieved 27 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Reconstruction of Euston Station". Sheffield Independent. British Newspaper Archive. 27 February 1937. Retrieved 27 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Bull, John. "The Euston Arch Part 2: Death". London Reconnections. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Station Facilities for London Euston". ATOC. n.d. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "The New Euston Station 1968" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2009.

- ↑ Williams, Michael (14 September 2007). "The real Eurostar: How a poet returned St Pancras to the nation". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ↑ Martin, Andrew (13 December 2004). "So, what would you burn?". New Statesman. London. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ↑ Stamp, Gavin (October 2007). "Steam ahead: the proposed rebuilding of London's Euston station is an opportunity to atone for a great architectural crime". Apollo: the international magazine of art and antiques. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- ↑ Morrison, Richard (10 April 2007). "Euston: we have an architectural problem". The Times. London. Retrieved 22 September 2007. (subscription required)

- ↑ "An Ode To Euston Station".

- ↑ Royal Institution of British Architects, "How We Built Britain" exhibition. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07zzr8r

- ↑ BBC On This Day 1973: "Bomb blasts rock Central London". Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/november/4/newsid_2538000/2538321.stm

- ↑ http://www.alwaystouchout.com/project/125 – Euston to Euston Square subway link

- ↑ Stewart, Dan (5 April 2007). "British Land wins £1bn Euston contract". Building.

- ↑ Binney, Marcus (18 February 2008). "Landmark of the railway age may be resurrected". The Times. London.(subscription required)

- ↑ – "Vision of Euston Station in the future"

- ↑ "Euston Station". Aedas. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Higgitt, Rebekah (18 July 2014). "Matthew Flinders bicentenary: statue unveiled to the most famous navigator you've probably never heard of". The Guardian Science blog. London. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Station Usage 2007/08" (PDF). Network Rail. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ↑ "Stations Run by Network Rail". Network Rail. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ↑ "Station facilities for London Euston". National Rail Enquiries. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Commercial information" (PDF). Complete National Rail Timetable. London: Network Rail. May 2013. p. 43. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Department for Transport (2010a). High Speed Rail – Command Paper (PDF). The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-10-178272-2. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ "High Speed Rail (Command Paper)" (PDF). Department for Transport. March 2010. p. 104.

- ↑ Cecil, Nicholas (28 February 2011). "High-speed trains 'will increase passenger numbers by 10,000' at Euston station". London Evening Standard.

- 1 2 Transport Select Committee, 28 June 2011, House of Commons

- ↑ Subject: Proposal for Examining the Potential Effect of High Speed 2 on London's Transport Network, Greater London Authority, 17 May 2011.

- ↑ High Speed Rail: Investing in Britain's Future Consultation, Department for Transport, February 2011.

- ↑ High Speed Rail London to the West Midlands and Beyond: A Report to Government by High Speed Two Limited: part 3 of 11 Archived 1 January 1970 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hall, Stanley (1990). The Railway Detectives. London: Ian Allan. p. 83. ISBN 0 7110 1929 0.

- ↑ Trevena, Arthur (1980). Trains in Trouble. Vol. 1. Redruth: Atlantic Books. p. 35. ISBN 0-906899-01-X.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/september/10/newsid_2504000/2504619.stm

- ↑ "HS2 fuels Crossrail 2 business case". TransportXtra. 21 December 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Euston station. |

- Station information on Euston railway station from Network Rail

- Euston Station and railway works – information about the old station from the Survey of London online.

- Euston Station Panorama

- Euston Arch Trust – the campaign for the return of the Euston Arch to the station with detailed history and gallery.

- The New Euston Station 1968 – 1968 British Rail information booklet about the rebuilt Euston station. Also includes historical information.

- Falco Completes Cycle Parking Installation at Euston Station