European Communities Act 1972 (UK)

|

| |

| Long title | An Act to make provision in connection with the enlargement of the European Communities to include the United Kingdom, together with (for certain purposes) the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man and Gibraltar. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1972 c. 68 |

| Territorial extent | United Kingdom & Gibraltar |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 17 October 1972 |

Status: Amended | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

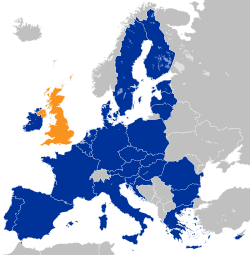

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| United Kingdom in the European Union |

|---|

|

|

Membership

Legislation |

|

The European Communities Act 1972 (c. 68) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which legislated for the accession of the United Kingdom to the European Economic Community (the Common Market), the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) and also legislated for the incorporation of European Union law (then Community law) into the domestic law of the United Kingdom. All three of these institutions would later form part of what is now known as the European Union and the act has been amended several times to give legal effect to the Single European Act, the Maastricht Treaty which formed the European Union and most recently the Treaty of Lisbon. It may or may not be repealed or amended[1] following the decision in the EU Referendum to "Leave the European Union" on Thursday 23 June 2016. In an interview with BBC News Theresa May promised that UK will introduce a bill to remove the European Communities Act 1972 (UK) from the statute book.[2]

Overview

The European Communities Act was the instrument whereby the UK was able to join the European Union (then known as the European Economic Community). It enables, under section 2(2), UK government ministers to lay regulations before Parliament to transpose EU Directives and rulings of the European Court of Justice into UK law. It also provides, in section 2(4), that all UK legislation, including primary legislation (Acts of Parliament) have effect "subject to" directly applicable EU law. This has been interpreted by UK courts as granting EU law primacy over domestic UK legislation. In the Factortame case, the House of Lords (Lord Bridge) has interpreted section 2(4) as effectively inserting an implied clause into all UK statutes that they shall not apply where they conflict with European law. This is seen by some as a departure from the British constitutional doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, as traditionally understood.[3]

Effect

As a matter of EU law, the primacy and direct effect of EU law is derived from the founding treaties of the union, and does not depend on any national constitutional provision or statute. However, this view has not been accepted by the British judiciary. As a matter of British constitutional law, the primacy of EU law derives solely from the European Communities Act. This means that if the Act were repealed,[4] any EU law (unless it has been transposed into British legislation) would, in practice, become unenforceable in the United Kingdom and Gibraltar, and the powers delegated by the Act to the EU institutions would return to the Parliament of the United Kingdom.[5]

The question of sovereignty had been discussed in an official document (FCO 30/1048) that became available to the public in January 2002 under the Thirty-year rule. It listed among "Areas of policy in which parliamentary freedom to legislate will be affected by entry into the European Communities": Customs duties, Agriculture, Free movement of labour, services and capital, Transport, and Social Security for migrant workers. The document concluded (paragraph 26) that it was advisable to put the considerations of influence and power before those of formal sovereignty.[6]

Repeal

The UK voted for British withdrawal from the EU in the June 2016 referendum. In October 2016 the prime minister, Theresa May, promised a "Great Repeal Bill" which would repeal the 1972 act and import its regulations into UK law, with effect from the date of British withdrawal. The regulations could then be amended or repealed on a case-by-case basis.[7]

In R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, the High Court held that under the act, the government did not have the power to trigger the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union using the royal prerogative. Through passing the European Communities Act, Parliament had made European Union law part of UK law, which could be undone only by the action of Parliament, under the principle of Parliamentary sovereignty.

See also

- European Communities Act 1972 (Ireland)

- Referendum Act 1975

- European Assembly Elections Act 1978

- European Parliamentary Elections Act 1993

- European Parliamentary Elections Act 1999

- European Parliamentary Elections Act 2002

- United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum, 1975

- European Union Act 2011

- European Union Referendum Act 2015

- UK renegotiation of EU membership, 2016

- United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016

-

Brexit, Article 50, and other articles – Wikipedia book

Brexit, Article 50, and other articles – Wikipedia book

Notes

- ↑ Allen Green, David (11 July 2016). "Is an Act of Parliament required for Brexit?". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ May, Theresa. "Brexit: PM to trigger Article 50 by end of March". BBC News.

- ↑ Elliott, M. "United Kingdom: Parliamentary sovereignty under pressure". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 2 (3): 545–627. doi:10.1093/icon/2.3.545.

- ↑ As British government could propose in Fall 2016: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-37532364

- ↑ Akehurst, Michael; Malanczuk, Peter (1997). Akehurst's Modern Introduction to International Law. London: Routledge. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-415-11120-1.

- ↑ FCO 30/1048, Legal and constitutional implications of UK entry into EEC (open from 1 January 2002).

- ↑ Mason, Rowena (2 October 2016). "Theresa May's 'great repeal bill': what's going to happen and when?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

Further reading

- Booker, C., and North, R., The Great Deception, Continuum Publishing London and New York, 2003. (EU Referendum Edition published by Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, April 2016)

.svg.png)