Crested penguin

| Crested penguin Temporal range: Miocene to present | |

|---|---|

1.jpg) | |

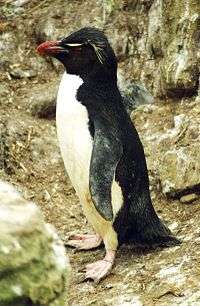

| Macaroni penguin, Eudyptes chrysolophus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Eudyptes Vieillot, 1816 |

| Species | |

|

Eudyptes chrysocome | |

The term crested penguin is the common name given collectively to species of penguins of the genus Eudyptes.[1] The exact number of species in the genus varies between four and seven depending on the authority, and a Chatham Islands species may have become extinct in the 19th century. All are black and white penguins with yellow crests, red bills and eyes, and are found on Subantarctic islands in the world's southern oceans. All lay two eggs, but raise only one young per breeding season; the first egg laid is substantially smaller than the second.

Taxonomy

The genus was described by the French ornithologist Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1816; the name is derived from the Ancient Greek words eu "good", and dyptes "diver".[2]

Six extant species have been classically recognised, with the recent splitting of the rockhopper penguin increasing it to seven. Conversely, the close relationship of the macaroni and royal penguins, and the erect-crested and Snares penguins have led some to propose that the two pairs should be regarded as species.[3]

Order Sphenisciformes

- Family Spheniscidae

- Fiordland penguin, Eudyptes pachyrhynchus

- Snares penguin, Eudyptes robustus – has been considered a subspecies of the Fiordland penguin

- Erect-crested penguin, Eudyptes sclateri

- Southern rockhopper penguin, Eudyptes chrysocome

- Eastern rockhopper penguin, Eudyptes (chrysocome) filholi

- Western rockhopper penguin, Eudyptes (chrysocome) chrysocome

- Northern rockhopper penguin, Eudyptes moseleyi – traditionally considered a subspecies of Eudyptes chrysocome as the rockhopper penguin.

- Royal penguin, Eudyptes schlegeli – sometimes considered a morph of E. chrysolophus

- Macaroni penguin, Eudyptes chrysolophus

- Chatham penguin, Eudyptes chathamensis (prehistoric?)

The Chatham Islands form is known only from subfossil bones, but may have become extinct as recently as the late 19th century as a bird kept captive at some time between 1867 and 1872[4] might refer to this taxon. It appears to have been a distinct species, with a thin, slim and low bill.

Evolution

Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA evidence suggests that the crested penguins split from the ancestors of their closest living relative, the yellow-eyed penguin, in the mid-Miocene around 15 million years ago, before splitting into separate species around 8 million years ago in the late Miocene.[5]

A fossil penguin genus, Madrynornis, has been identified as the closest known relative of the crested penguins. Found in late Miocene deposits dated to about 10 million years ago, it must have separated from the crested penguins around 12 million years ago. Given that the head ornamentation by yellow filoplumes seems plesiomorphic for the Eudyptes-Megadyptes lineage, Madrynornis probably had them too.

Description

The crested penguins are all similar in appearance, having sharply delineated black and white plumage with red beaks and prominent yellow crests. Their calls are more complex than those of other species, with several phrases of differing lengths.[6] The royal penguin (mostly) has a white face, while other species have black faces.

Breeding

Crested penguins breed on Subantarctic islands in the southern reaches of the world's oceans; the greatest diversity occurring around New Zealand and surrounding islands. Their breeding displays and behaviours are generally more complex than other penguin species.[7] Both male and female parents take shifts incubating eggs and young.[8]

Crested penguins lay two eggs, but almost always raise only one young successfully. All species exhibit the odd phenomenon of egg-size dimorphism in breeding; the first egg (or A-egg) laid is substantially smaller than the second egg (B-egg). This is most extreme in the macaroni penguin, where the first egg averages only 60% the size of the second.[9] The reason for this is a mystery remains unknown, although several theories have been proposed. British ornithologist David Lack theorized that the genus was evolving toward the laying of a one-egg clutch.[10] Experiments with egg substitution have shown that A-eggs can produce viable chicks that were only 7% lighter at time of fledging.[11] Physiologically, the first egg is smaller because it develops while the mother is still at sea swimming and thus has less energy to invest in the egg.[12]

Recently, brooding royal and erect-crested penguins have been reported to tip the smaller eggs out as the second is laid.

Species photographs

Photographs of adults of the extant (living) species are shown:

- Surviving species

-

Royal penguin

Eudyptes schlegeli -

Southern rockhopper penguin

Eudyptes chrysocome -

Northern rockhopper penguin

Eudyptes moseleyi -

.jpg)

Fiordland penguin

Eudyptes pachyrhynchus -

.jpg)

Snares penguin

Eudyptes robustus -

6.jpg)

Macaroni penguin

Eudyptes chrysolophus

References

- ↑ "ITIS Standard Report Page: Eudyptes".

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George & Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ Christidis L, Boles WE (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. Canberra: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6.

- ↑ A.J.D. Tennyson and P.R. Millener (1994). Bird extinctions and fossil bones from Mangere Island, Chatham Islands, Notornis (Supplement) 41, 165–178.

- ↑ Baker AJ, Pereira SL, Haddrath OP, Edge KA (2006). "Multiple gene evidence for expansion of extant penguins out of Antarctica due to global cooling". Proc Biol Sci. 273 (1582): 11–17. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3260. PMC 1560011

. PMID 16519228.

. PMID 16519228. - ↑ Williams (The Penguins) p. 69

- ↑ Williams (The Penguins) p. 52

- ↑ Williams (The Penguins) p. 76

- ↑ Williams (The Penguins) p. 38

- ↑ Lack, David (1968). Ecological Adaptations for breeding in birds. London: Methuen.

- ↑ Williams, Tony D (1990). "Growth and survival in the Macaroni Penguin Eudyptes chrysolophus, A- and B-chicks: do females maximise investment in the large B-egg". Oikos. 59 (3): 349–54. doi:10.2307/3545145. JSTOR 3545145.

- ↑ Young, Ed (4 October 2016). "Why Crested Penguins Always Lay Doomed Eggs". National Geographic (magazine). Retrieved 10 October 2016.

Cited text

- Williams, Tony D (1995). The Penguins. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854667-X.

External links

- TerraNature Three Eudyptes species endemic to New Zealand