Essential fatty acid

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| See also |

Essential fatty acids, or EFAs, are fatty acids that humans and other animals must ingest because the body requires them for good health but cannot synthesize them.[1]

The term "essential fatty acid" refers to fatty acids required for biological processes but does not include the fats that only act as fuel. Essential fatty acids should not be confused with essential oils, which are "essential" in the sense of being a concentrated essence.

Only two fatty acids are known to be essential for humans: alpha-linolenic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid) and linoleic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid).[2] Some other fatty acids are sometimes classified as "conditionally essential," meaning that they can become essential under some developmental or disease conditions; examples include docosahexaenoic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid) and gamma-linolenic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid).

When the two EFAs were discovered in 1923, they were designated "vitamin F", but in 1929, research on rats showed that the two EFAs are better classified as fats rather than vitamins.[3]

Functions

- The biological effects of the ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids are mediated by their mutual interactions, see Essential fatty acid interactions for detail.

In the body, essential fatty acids serve multiple functions. In each of these, the balance between dietary ω-3 and ω-6 strongly affects function.

- They are modified to make

- the classic eicosanoids (affecting inflammation and many other cellular functions)

- the endocannabinoids (affecting mood, behavior and inflammation)

- the lipoxins which are a group of eicosanoid derivatives formed via the lipoxygenase pathway from ω-6 EFAs and resolvins from ω-3 (in the presence of acetylsalicylic acid, downregulating inflammation)

- the isofurans, neurofurans, isoprostanes, hepoxilins, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and Neuroprotectin D

- They form lipid rafts (affecting cellular signaling)[4]

- They act on DNA (activating or inhibiting transcription factors such as NF-κB, which is linked to pro-inflammatory cytokine production)[5]

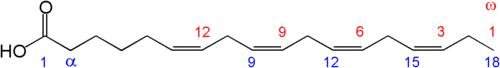

Fatty acids are straight chain hydrocarbons possessing a carboxyl (COOH) group at one end. The carbon next to the carboxylate is known as α, the next carbon β, and so forth. Since biological fatty acids can be of different lengths, the last position is labelled as a "ω", the last letter in the Greek alphabet. Since the physiological properties of unsaturated fatty acids largely depend on the position of the first unsaturation relative to the end position and not the carboxylate. For example, the term ω-3 signifies that the first double bond exists as the third carbon-carbon bond from the terminal CH3 end (ω) of the carbon chain. The number of carbons and the number of double bonds is also listed.

ω-3 18:4 (stearidonic acid) or 18:4 ω-3 or 18:4 n−3 indicates an 18-carbon chain with 4 double bonds, and with the first double bond in the third position from the CH3 end. Double bonds are cis and separated by a single methylene (CH2) group unless otherwise noted. So in free fatty acid form, the chemical structure of stearidonic acid is:

Examples

- For complete tables of ω-3 and ω-6 essential fatty acids, see Polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The essential fatty acids start with the short chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (SC-PUFA):

- ω-3 fatty acids:

- α-Linolenic acid or ALA (18:3n-3)

- ω-6 fatty acids:

- Linoleic acid or LA (18:2n-6)

These two fatty acids cannot be synthesized by humans because humans lack the desaturase enzymes required for their production.

They form the starting point for the creation of longer and more desaturated fatty acids, which are also referred to as long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA):

- ω-3 fatty acids:

- eicosapentaenoic acid or EPA (20:5n-3)

- docosahexaenoic acid or DHA (22:6n-3)

- ω-6 fatty acids:

- gamma-linolenic acid or GLA (18:3n-6)

- dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid or DGLA (20:3n-6)

- arachidonic acid or AA (20:4n-6)

ω-9 fatty acids are not essential in humans because they can be synthesized from carbohydrates or other fatty acids.

Essential fatty acids

Mammals lack the ability to introduce double bonds in fatty acids beyond carbon 9 and 10, hence ω-6 linoleic acid (18:2,9,12), abbreviated LA (18:2n-6), and the ω-3 linolenic acid (18:3,9,12,15), abbreviated ALA (18:3n-3), are essential for humans in the diet. In humans, arachidonic acid (20:4,5,8,11,14, abbreviated 20:4n-6) can be synthesized from LA by alternative desaturation and chain elongation.

Humans can convert both LA and ALA to docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3; DHA) respectively, although the conversion to DHA is limited, resulting in lower blood levels of DHA than through direct ingestion. This is illustrated by studies in vegans and vegetarians.[6] If there is relatively more LA than ALA in the diet it favors the formation of docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-6) from LA rather than docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3) from ALA. This effect can be altered by changing the relative ratio of LA:ALA, but is more effective when total intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids is low. However, the capacity to convert LA to AA and ALA to DHA in the preterm infant is limited, and preformed AA and DHA may be required to meet the needs of the developing brain. Both AA and DHA are present in breastmilk and contribute along with the parent fatty acids LA and ALA to meeting the requirements of the newborn infant. Many infant formulas have AA and DHA added to them with an aim to make them more equivalent to human milk.

Essential nutrients are defined as those that cannot be synthesized de novo in sufficient quantities for normal physiological function. This definition is met for LA and ALA but not the longer chain derivatives in adults.[7] The longer chain derivatives particularly, however, have pharmacological properties that can modulate disease processes, but this should not be confused with dietary essentiality.

Between 1930 and 1950, arachidonic acid and linolenic acid were termed 'essential' because each was more or less able to meet the growth requirements of rats given fat-free diets. However, they were yet to be recognized as essential nutrients for humans. In the 1950s Arild Hansen showed that infants fed skimmed milk developed essential fatty acid deficiency. It was characterized by an increased food intake, poor growth, and a scaly dermatitis, and was cured by the administration of corn oil.

Later work by Hansen randomized 426 children, mainly black, to four treatments: modified cow's milk formula, skimmed milk formula, skimmed milk formula with coconut oil, or cow's milk formula with corn oil. The infants who received the skimmed milk formula or the formula with coconut oil developed essential fatty acid deficiency signs and symptoms. This could be cured by administration of ethyl linoleate (the ethyl ester of linoleic acid) with about 1% of the energy intake.[8]

Collins et al. 1970[9] were the first to demonstrate linoleic acid deficiency in adults. They found that patients undergoing intravenous nutrition with glucose became isolated from their fat supplies and rapidly developed biochemical signs of essential fatty acid deficiency (an increase in 20:3n-9/20:4n-6 ratio in plasma) and skin symptoms. This could be treated by infusing lipids, and later studies showed that topical application of sunflower oil would also resolve the dermal symptoms.[10] Linoleic acid has a specific role in maintaining the skin water-permeability barrier, probably as constituents of acylglycosylceramides. This role cannot be met by any ω-3 fatty acids or by arachidonic acid.

The main physiological requirement for ω-6 fatty acids is attributed to arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is the major precursor of prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and anandamides that play a vital role in cell signaling. Metabolites from the ω-3 pathway, mainly from eicosapentaenoic acid, are mostly inactive, and this explains why ω-3 fatty acids do not correct the reproductive failure in rats where arachidonic is needed to make active prostaglandins that cause uterine contraction.[11] To some extent, any ω-3 or ω-6 can contribute to the growth-promoting effects of EFA deficiency, but only ω-6 fatty acids can restore reproductive performance and correct the dermatitis in rats. Particular fatty acids are still needed at critical life stages (e.g. lactation) and in some disease states.

In nonscientific writing, common usage is that the term essential fatty acid comprises all the ω-3 or -6 fatty acids. Conjugated fatty acids like calendic acid are not considered essential. Authoritative sources include the whole families, but generally only make dietary recommendations for LA and ALA with the exception of DHA for infants under the age of 6 months. Recent reviews by WHO/FAO in 2009 and the European Food Safety Authority[12] have reviewed the evidence and made recommendations for minimal intakes of LA and ALA and have also recommended intakes of longer chain ω-3 fatty acids based on the association of oily fish consumption with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease. Some earlier review lumped all polyunsaturated fatty acids together without qualification whether they were short or long-chain PUFA or whether they were ω-3 and ω-6 PUFA.[13][14][15]

Traditionally speaking, the LC-PUFAs are not essential. Because the LC-PUFA are sometimes required, they may be considered "conditionally essential", or not essential to healthy adults.[16]

Some of the food sources of ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids are fish and shellfish, flaxseed (linseed) and flaxseed oil, hemp seed, olive oil, soya oil, canola (rapeseed) oil, chia seeds, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, leafy vegetables, and walnuts; but most of these food sources are poor sources of EFA's. Flaxseed are the best source of ω-3 EFA, next is chiaseed, lastly hempseed; sunflower and starflower seeds are the best sources of ω-6 EFA.

Essential fatty acids play a part in many metabolic processes, and there is evidence to suggest that low levels of essential fatty acids, or the wrong balance of types among the essential fatty acids, may be a factor in a number of illnesses, including osteoporosis.[17]

Fish is the main source of the heart disease-fighting omega-3 fats eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), but some plant-based foods also contain omega-3 in the form of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), which also helps heart health.[18] The human body can (and in case of a purely vegetarian diet often must unless certain algae or supplements derived from them are consumed) convert α-linolenic acid (ALA) to EPA and subsequently DHA. This however requires more metabolic work, which is thought to be the reason that the absorption of essential fatty acids is much greater from animal rather than plant sources.

The IUPAC Lipid Handbook provides a very large and detailed listing of fat contents of animal and vegetable fats, including ω-3 and -6 oils.[19] The National Institutes of Health's EFA Education group publishes Essential Fats in Food Oils.[20] This lists 40 common oils, more tightly focused on EFAs and sorted by n-6:3 ratio. Vegetable Lipids as Components of Functional Food lists notable vegetable sources of EFAs as well as commentary and an overview of the biosynthetic pathways involved.[21] Careful readers will note that these sources are not in excellent agreement. EFA content of vegetable sources varies with cultivation conditions. Animal sources vary widely, both with the animal's feed and that the EFA makeup varies markedly with fats from different body parts.

Human health

Almost all the polyunsaturated fats in the human diet are EFAs. Essential fatty acids play an important role in the life and death of cardiac cells.[22][23][24][25]

Essential fatty acid deficiency

Essential fatty acid deficiency results in a dermatitis similar to that seen in zinc or biotin deficiency.[26]:485

Biologist Ray Peat has claimed there are flaws in the studies showing the need for ω-3 and ω-6 (also called n-3 and n-6) fats. He further claims that EFA deficiencies have sometimes been reversed by adding B vitamins or a fat-free liver extract to the diet. In his view, 'the optimal dietary level of the "essential fatty acids" might be close to zero, if other dietary factors were also optimized.'[27] However, these views are contrary to the scientific consensus.

Treatment for depression

Research suggests that high intakes of fish and omega-3 fatty acids are linked to decreased rates of major depression. Omega-3 fatty acids, such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are important for enzymatic pathways required to metabolize long-chain (i.e. 14 to 22 carbons) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Low plasma concentrations of DHA predict low concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). It is found that low concentrations of 5-HIAA in the brain is associated with depression and suicide.[28]

There are high concentrations of DHA in synaptic membranes of the brain. This is critical for synaptic transmission and membrane fluidity. The omega-6 fatty acid to omega-3 fatty acid ratio is important to avoid imbalance of membrane fluidity. Membrane fluidity affects function of enzymes such as adenylate cyclase and ion channels such as calcium, potassium, and sodium, which in turn affects receptor numbers and functioning, as well as serotonin neurotransmitter levels. It is evident that western diets are deficient in omega-3 and excessive in omega-6, and balancing of this ratio would confer numerous health benefits.[29]

Clinical research suggests a benefit of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of depression during the perinatal period.[28] A meta-analysis of trials of EPA supplements for depression in non-pregnant adults concluded that supplements with more than 60% EPA are effective, but those containing primarily DHA, or less than 60% EPA, were not effective.[30]

See also

- Eicosanoid

- Specialized proresolving mediators

- Endogenous cannabinoid

- Essential amino acid

- Essential fatty acid interactions

- Fatty acid metabolism

- Fatty acid synthase

- Nonclassic eicosanoid

- Oily fish

- Omega-3 fatty acid

- Omega-6 fatty acid

- Polyunsaturated fat

References

- ↑ Robert S. Goodhart; Maurice E. Shils (1980). Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lea and Febinger. pp. 134–138. ISBN 0-8121-0645-8.

- ↑ Whitney Ellie; Rolfes SR (2008). Understanding Nutrition (11th ed.). California: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 154.

- ↑ Burr, G.O., Burr, M.M. and Miller, E. (1930). "On the nature and role of the fatty acids essential in nutrition" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 86 (587). Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Stillwell W, Shaikh SR, Zerouga M, Siddiqui R, Wassall SR (2005). "Docosahexaenoic acid affects cell signaling by altering lipid rafts". Reproduction, Nutrition, Development. 45 (5): 559–79. doi:10.1051/rnd:2005046. PMID 16188208.

- ↑ Calder PC (December 2004). "n-3 fatty acids, inflammation, and immunity--relevance to postsurgical and critically ill patients". Lipids. 39 (12): 1147–61. doi:10.1007/s11745-004-1342-z. PMID 15736910.

- ↑ Sanders TA. DHA Status of vegetarians. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essential Fatty Acids 2009; 81(2-3):137-41. doi:10.1016/j.plefa.2009.05.013 PMID 19500961

- ↑ FAO/WHO Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition. Report of an expert consultation. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 91, Rome 2011. ISSN 0254-4725

- ↑ Wiese, H; Hansen, A; Adams, DJ (1958). "Text". Journal of Nutrition. 66 (3): 345–360. PMID 13611579.

- ↑ "Plasma lipids in human linoleic acid deficiency.". Nutr Metab. 13 (3): 150–67. 1971. doi:10.1159/000175332. PMID 5001758.

- ↑ Prottey, C; Hartop, PJ; Press, M (1975). "Correction of the cutaneous manifestations of essential fatty acid deficiency in man by application of sunflower-seed oil to the skin.". J Invest Dermatol. 64 (4): 228–34. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12510667. PMID 1117180.

- ↑ Sanders T and Emery P. The Molecular Basis of Human Nutrition, Taylor Frances, London, 2003 ISBN 0-748-40753-7

- ↑ Jones, A (2010). "EFSA Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids and cholesterol". EFSA Journal. 8 (3): 1461. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1461.

- ↑ Heather Hutchins, MS, RD (2005-10-19). "Symposium Highlights -- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Recommendations for Therapeutics and Prevention".

Omega-3 fatty acids and their counterparts, n-6 fatty acids, are essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) because they cannot be synthesized de novo in the body.

- ↑ Nugent KP, Spigelman AD, Phillips RK (June 1996). "Tissue prostaglandin levels in familial adenomatous polyposis patients treated with sulindac". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 39 (6): 659–62. doi:10.1007/BF02056946. PMID 8646953.

Arachidonic acid is an essential fatty acid…

- ↑ Carlstedt-Duke J, Brönnegård M, Strandvik B (December 1986). "Pathological regulation of arachidonic acid release in cystic fibrosis: the putative basic defect". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (23): 9202–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.23.9202. PMC 387103

. PMID 3097647.

. PMID 3097647. [T]he turnover of essential fatty acids is increased (7). Arachidonic acid is one of the essential fatty acids affected.

- ↑ Cunnane SC (November 2003). "Problems with essential fatty acids: time for a new paradigm?". Progress in Lipid Research. 42 (6): 544–68. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(03)00038-9. PMID 14559071.

- ↑ Kruger MC, Horrobin DF (September 1997). "Calcium metabolism, osteoporosis and essential fatty acids: a review". Progress in Lipid Research. 36 (2–3): 131–51. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(97)00007-6. PMID 9624425.

- ↑ Cleveland Clinic - Plant Sources of omega 3s

- ↑ IUPAC Lipid Handbook

- ↑ Essential Fats in Food Oils

- ↑ Vegetable Lipids as Components of Functional Food, Stuchlik and Zak

- ↑ Honoré E, Barhanin J, Attali B, Lesage F, Lazdunski M (March 1994). "External blockade of the major cardiac delayed-rectifier K+ channel (Kv1.5) by polyunsaturated fatty acids". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (5): 1937–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1937. PMC 43279

. PMID 8127910.

. PMID 8127910. - ↑ Reiffel JA, McDonald A (August 2006). "Antiarrhythmic effects of omega-3 fatty acids". The American Journal of Cardiology. 98 (4A): 50i–60i. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.027. PMID 16919517.

- ↑ Landmark K, Alm CS (November 2006). "[Alpha-linolenic acid, cardiovascular disease and sudden death]". Tidsskrift for Den Norske Lægeforening (in Norwegian). 126 (21): 2792–4. PMID 17086218.

- ↑ Herbaut C (September 2006). "[Omega-3 and health]". Revue médicale de Bruxelles (in French). 27 (4): S355–60. PMID 17091903.

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ http://raypeat.com/articles/nutrition/oils-in-context.shtml

- 1 2 Rees AM, Austin MP, Parker G (April 2005). "Role of omega-3 fatty acids as a treatment for depression in the perinatal period". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 39 (4): 274–80. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2005.01565.x. PMID 15777365.

- ↑ Logan AC (November 2004). "Omega-3 fatty acids and major depression: a primer for the mental health professional". Lipids in Health and Disease. 3 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-3-25. PMC 533861

. PMID 15535884.

. PMID 15535884. - ↑ Sublette, ME; Ellis, SP; Geant, AL; Mann, JJ (2011). "Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 72 (12): 1577–84. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06634. PMC 3534764

. PMID 21939614.

. PMID 21939614.