Mastocytosis

| Mastocytosis | |

|---|---|

| |

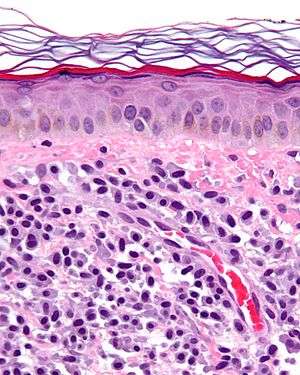

| Micrograph of mastocytosis. Skin biopsy. H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Oncology, allergology, hematology |

| ICD-10 | Q82.2, C96.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 757.33, 202.6 |

| ICD-O | 9741/3 |

| OMIM | 154800 |

| DiseasesDB | 7864 |

| eMedicine | derm/258 med/1401 |

| MeSH | D008415 |

Mastocytosis, one of the mast cell diseases, is a rare mast cell activation disorder of both children and adults caused by the presence of too many mast cells (mastocytes) and CD34+ mast cell precursors.[1]

People affected by mastocytosis are susceptible to itching, hives, and anaphylactic shock, caused by the release of histamine from mast cells. The current classifications, definitions and diagnostic criteria for mastocytosis are being reviewed for revision to better describe the collection of related disorders.[2]

Classification

Mastocytosis can occur in a variety of forms:

- Most cases are cutaneous (confined to the skin only), and there are several forms. The most common cutaneous mastocytosis is urticaria pigmentosa (UP), more common in children, although also seen in adults. Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP) is a much rarer form of cutaneous mastocytosis that affects adults.[3] UP and TMEP can evolve into indolent systemic mastocytosis. This should be considered if patients develop any systemic symptoms .[4]

- Systemic mastocytosis involves the bone marrow in some cases and in some cases other internal organs, usually in addition to involving the skin. Any organ can be involved. Mast cells collect in various tissues and can affect organs where mast cells do not normally inhabit such as the liver, spleen and lymph nodes, and organs which have normal populations but numbers are increased. In the bowel, it may manifest as mastocytic enterocolitis.[5]

- Generalized eruption of cutaneous mastocytosis (adult type) is the most common pattern of mastocytosis presenting to the dermatologist, with the most common lesions being macules, papules, or nodules that are disseminated over most of the body but especially on the upper arms, legs, and trunk.[6]:616

- Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis' has diffuse involvement in which the entire integument may be thickened and infiltrated with mast cells to produce a peculiar orange color, giving rise to the term "homme orange."[6]:616

There are three classes of systemic mastocytosis: indolent systemic mastocytosis, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, and Leukemic systemic (which affects 3% of cases).

Mast cell diseases

Other types of mast cell disease include:

- Monoclonal mast cell activation, defined by the World Health Organisation definitions 2010, also has increased mast cells but insufficient to be systemic mastocytosis (in World Health Organisation Definitions)[7]

- Mast cell activation syndrome – has normal number of mast cells, but all the symptoms and in some cases the genetic markers of systemic mastocytosis.[7]

- Other known but rare mast cell proliferation diseases are mast cell leukemia and mast cell sarcoma.

Signs and symptoms

When too many mast cells exist in a person's body and undergo degranulation, the additional chemicals can cause a number of symptoms which can vary over time and can range in intensity from mild to severe. Because mast cells play a role in allergic reactions, the symptoms of mastocytosis often are similar to the symptoms of an allergic reaction. They may include, but are not limited to:[8]

- Fatigue

- Skin lesions (urticaria pigmentosa), itching, and dermatographic urticaria (skin writing)

- Abdominal discomfort

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Olfactive intolerance

- Infections (bronchitis, rhinitis, and conjunctivitis)

- Ear/nose/throat inflammation

- Anaphylaxis (shock from allergic or immune causes)

- Episodes of very low blood pressure (including shock) and faintness

- Bone or muscle pain

- Decreased bone density or increased bone density (osteoporosis or osteosclerosis)

- Headache

- Depression[9]

- Ocular discomfort

- Increased stomach acid production causing peptic ulcers (increased stimulation of enterochromaffin cell and direct histamine stimulation on parietal cell)

- Malabsorption (due to inactivation of pancreatic enzymes by increased acid)[10]

Pathophysiology

Mast cells are located in connective tissue, including the skin, the linings of the stomach and intestine, and other sites. They play an important role in helping defend these tissues from disease. By releasing chemical "alarms" such as histamine, mast cells attract other key players of the immune defense system to areas of the body where they are needed.

Mast cells seem to have other roles as well. Because they gather together around wounds, mast cells may play a part in wound healing. For example, the typical itching felt around a healing scab may be caused by histamine released by mast cells. Researchers also think mast cells may have a role in the growth of blood vessels (angiogenesis). No one with too few or no mast cells has been found, which indicates to some scientists we may not be able to survive with too few mast cells.

Mast cells express a cell surface receptor, c-kit[11] (CD117), which is the receptor for stem cell factor (scf). In laboratory studies, scf appears to be important for the proliferation of mast cells. Mutations of the c-kit receptor, leading to uncontrolled stimulation of the receptor, is a cause for the disease. Inhibiting the tyrosine kinase receptor with imatinib (see below) may reduce the symptoms of mastocytosis.

Diagnosis

Doctors can diagnose urticaria pigmentosa (cutaneous mastocytosis, see above) by seeing the characteristic lesions that are dark-brown and fixed. A small skin sample (biopsy) may help confirm the diagnosis.

By taking a biopsy from a different organ, such as the bone marrow, the doctor can diagnose systemic mastocytosis. Using special techniques on a bone marrow sample, the doctor looks for an increase in mast cells. Another sign of this disorder is high levels of certain mast-cell chemicals and proteins in a person's blood and sometimes in the urine. Serum tryptase level is the initial screening test for suspected systemic mastocytosis.

Epidemiology

No one is sure how many people have either type of mastocytosis, but mastocytosis generally has been considered to be an "orphan disease" (orphan diseases affect 200,000 or fewer people in the United States). Mastocytosis, however, often may be misdiagnosed, especially because it typically occurs secondary to another condition, and thus may occur more frequently than assumed.

Treatment

There is currently no cure for mastocytosis, but there are a number of medicines to help treat the symptoms:

- Antihistamines block receptors targeted by histamine released from mast cells. Both H1 and H2 blockers may be helpful.

- Leukotriene antagonists block receptors targeted by leukotrienes released from mast cells.

- Mast cell stabilizers help prevent mast cells from releasing their chemical contents. Cromolyn sodium oral solution (Gastrocrom / Cromoglicate) is the only medicine specifically approved by the FDA for the treatment of mastocytosis. Ketotifen is available in Canada and Europe, but is only available in the U.S. as eyedrops (Zaditor).

- Proton pump inhibitors help reduce production of gastric acid, which is often increased in patients with mastocytosis. Excess gastric acid can harm the stomach, esophagus, and small intestine.

- Epinephrine constricts blood vessels and opens airways to maintain adequate circulation and ventilation when excessive mast cell degranulation has caused anaphylaxis.

- Salbutamol and other beta-2 agonists open airways that can constrict in the presence of histamine.

- Corticosteroids can be used topically, inhaled, or systemically to reduce inflammation associated with mastocytosis.

Antidepressants are an important and often overlooked tool in the treatment of mastocytosis. Depression and other neurological symptoms have been noted in mastocytosis.[12][13] Some antidepressants, such as doxepin, are themselves potent antihistamines and can help relieve physical as well as cognitive symptoms.

Dihydropyridines and calcium channel blockers are sometimes used to treat high blood pressure. At least one clinical study suggested nifedipine, one of the dihydropyridines, may reduce mast cell degranulation in patients who exhibit urticaria pigmentosa. A 1984 study by Fairly et al. included a patient with symptomatic urticaria pigmentosa who responded to nifedipine at dose of 10 mg po tid.[14] However, nifedipine has not been approved by the FDA for treatment of mastocytosis.

In rare cases in which mastocytosis is cancerous or associated with a blood disorder, the patient may have to use steroids and/or chemotherapy. The novel agent imatinib (Glivec or Gleevec) has been found to be effective in certain types of mastocytosis.[15]

There are clinical trials currently underway testing stem cell transplants as a form of treatment.

Research

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases scientists have been studying and treating patients with mastocytosis for several years at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center.

Some of the most important research advances for this rare disorder include improved diagnosis of mast cell disease and identification of growth factors and genetic mechanisms responsible for increased mast cell production. Researchers are currently evaluating approaches to improve ways to treat mastocytosis.

Scientists also are focusing on identifying disease-associated mutations (changes in genes). NIH scientists have identified some mutations, which may help researchers understand the causes of mastocytosis, improve diagnosis, and develop better treatments.

History

Urticaria pigmentosa was first described in 1869.[16] Systemic mastocytosis was first reported by French scientists in 1936.[17]

See also

- Mast cell tumors are found in many species of animals.

References

- ↑ Horny HP, Sotlar K, Valent P (2007). "Mastocytosis: state of the art". Pathobiology. 74 (2): 121–32. doi:10.1159/000101711. PMID 17587883.

- ↑ http://www.mastocytosis.ca/masto.htm

- ↑ Ellis DL (1996). "Treatment of telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans with the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped dye laser". Dermatol Surg. 22 (1): 33–7. doi:10.1016/1076-0512(95)00388-6. PMID 8556255.

- ↑ Noack F, Escribano L, Sotlar K, Nunez R, Schuetze K, Valent P, Horny HP (2003). "Evolution of urticaria pigmentosa into indolent systemic mastocytosis: abnormal immunophenotype of mast cells without evidence of c-kit mutation ASP-816-VAL". Leuk Lymphoma. 44 (2): 313–9. doi:10.1080/1042819021000037967. PMID 12688351.

- ↑ Ramsay DB, Stephen S, Borum M, Voltaggio L, Doman DB (2010). "Mast cells in gastrointestinal disease". Gastroenterology Hepatology (N Y). 2010 (12): 772–7. PMC 3033552

. PMID 21301631.

. PMID 21301631. - 1 2 James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- 1 2 Akin C, Valent P, Metcalfe DD (2010). "Mast cell activation: proposed diagnostic criteria". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 126 (6): 1099–104. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.035. PMC 3753019

. PMID 21035176.

. PMID 21035176. - ↑ Hermine O, Lortholary O, Leventhal PS, et al. (2008). Soyer HP, ed. "Case-Control Cohort Study of Patients' Perceptions of Disability in Mastocytosis". PLoS ONE. 3 (5): e2266. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002266. PMC 2386235

. PMID 18509466.

. PMID 18509466.

- ↑ Depression in Patients with Mastocytosis: Prevalence, Features and Effects of Masitinib Therapy

- ↑ Lee, JK; Whittaker, SJ; Enns, RA; Zetler, P (Dec 7, 2008). "Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic mastocytosis". World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 14 (45): 7005–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.7005. PMID 19058339.

- ↑ Orfao A, Garcia-Montero AC, Sanchez L, Escribano L (2007). "Recent advances in the understanding of mastocytosis: the role of KIT mutations". Br. J. Haematol. 138 (1): 12–30. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06619.x. PMID 17555444.

- ↑ Moura DS, Sultan S, Georgin-Lavialle S, Pillet N, Montestruc F, et al. (2011). "Depression in Patients with Mastocytosis: Prevalence, Features and Effects of Masitinib Therapy". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e26375. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026375.

- ↑ Rogers MP, Bloomingdale K, Murawski BJ, Soter NA, Reich P, Austen KF (1986). "Mixed organic brain syndrome as a manifestation of systemic mastocytosis". Psychosom Med. 48 (6): 437–47. doi:10.1097/00006842-198607000-00006. PMID 3749421.

- ↑ Fairley JA, Pentland AP, Voorhees JJ (1984). "Urticaria pigmentosa responsive to nifedipine". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 11 (4 Pt 2): 740–3. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(84)70233-7. PMID 6491000.

- ↑ Droogendijk HJ, Kluin-Nelemans HJ, van Doormaal JJ, Oranje AP, van de Loosdrecht AA, van Daele PL (2006). "Imatinib mesylate in the treatment of systemic mastocytosis: a phase II trial". Cancer. 107 (2): 345–51. doi:10.1002/cncr.21996. PMID 16779792.

- ↑ Nettleship E, Tay W (1869). "Reports of Medical and Surgical Practice in the Hospitals of Great Britain". Br Med J. 2 (455): 323–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.455.323. PMC 2260962

. PMID 20745623.

. PMID 20745623. - ↑ Sézary A, Levy-Coblentz G, Chauvillon P (1936). "Dermographisme et mastocytose". Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphilol. 43: 359–61.

External links

- The Mastocytosis Society, Inc.

- Mastokids.org

- Mastocytosis Society Canada

- Mastopedia Information and Support Group

- UK Mastocytosis Support

- The Australasian Mastocytosis Foundation

- Cancer.Net Mastocytosis

- The Many Faces of Mastocytosis

- International Community for Mastocytosis