Environmental art

Environmental art is a range of artistic practices encompassing both historical approaches to nature in art and more recent ecological and politically motivated types of works.[1][2] Environmental art has evolved away from formal concerns, worked out with earth as a sculptural material, towards a deeper relationship to systems, processes and phenomena in relationship to social concerns.[3] Integrated social and ecological approaches developed as an ethical, restorative stance emerged in the 1990s.[4] Over the past ten years environmental art has become a focal point of exhibitions around the world as the social and cultural aspects of climate change come to the forefront.

The term "environmental art" often encompasses "ecological" concerns but is not specific to them.[5] It primarily celebrates an artist's connection with nature using natural materials.[1][2] The concept is best understood in relationship to historic earth/Land art and the evolving field of ecological art. The field is interdisciplinary in the fact that environmental artists embrace ideas from science and philosophy. The practice encompasses traditional media, new media and critical social forms of production. The work embraces a full range of landscape/environmental conditions from the rural, to the suburban and urban as well as urban/rural industrial.

History: Landscape painting and representation

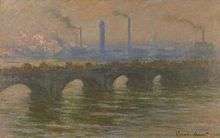

It can be argued that environmental art began with the Paleolithic cave paintings of our ancestors. While no landscapes have (yet) been found, the cave paintings represented other aspects of nature important to early humans such as animals and human figures. "They are prehistoric observations of nature. In one-way or another, nature for centuries remained the preferential theme of creative art." [6] More modern examples of environmental art stem from landscape painting and representation. When artists painted onsite they developed a deep connection with the surrounding environment and its weather and brought these close observations into their canvases. John Constable’s sky paintings “most closely represent the sky in nature.”[7] Monet’s London Series also exemplifies the artist’s connection with the environment. “For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life, the air and the light, which vary continually for me, it is only the surrounding atmosphere that gives subjects their true value."[8]

Contemporary painters, such as Diane Burko represent natural phenomena - and its change over time - to convey ecological issues, drawing attention to climate change.[9][10] Alexis Rockman's landscapes depict a sardonic view of climate change and humankind's interventions with other species by way of genetic engineering.[11]

Challenging traditional sculptural forms

It is possible to trace the growth of environmental art as a "movement", beginning in the late 1960s or the 1970s. In its early phases it was most associated with sculpture—especially Site-specific art, Land art and Arte povera—having arisen out of mounting criticism of traditional sculptural forms and practices which were increasingly seen as outmoded and potentially out of harmony with the natural environment.

In October 1968 Robert Smithson organized an exhibition at Dwan Gallery in New York titled Simply “Earthworks”. All of the works posed an explicit challenge to conventional notions of exhibition and sales, in that they were either too large or too unwieldy to be collected; most were represented only by photographs, further emphasizing their resistance to acquisition.[12] For these artists escaping the confines of the gallery and modernist theory was achieved by leaving the cities and going out into the desert.

”They were not depiciting the landscape, but engaging it; their art was not simply of the landscape, but in it as well.”[13] This shift in the late 60’s and 70’s represents an avant garde notion about sculpture, the landscape and our relationship with it. The work challenged the conventional means to create sculpture, but also defied the high art modes of dissemination and exhibition of the work, such as the Dawn Gallery show mentioned earlier. This shift opened up a new space and in doing so expanded the ways in which work was documented and conceptualized.[14]

In Europe, among many others, artists like Nils Udo, Jean-Max Albert,[15][16] Piotr Kowalski[17] had been creating environmental art since the 1960s.

.jpg)

Entering public and urban spaces

In 1978 Barry Thomas and friends illegally occupied a vacant CBD lot in Wellington New Zealand. He dumped a truck load of topsoil then planted 180 cabbage seedlings in the shape of the word "Cabbage" for his 'vacant lot of cabbages. The site was then inundated with contributing artists' work - the whole event lasted 6 months and ended with a week long festival celebrating native trees and forests. In 2012, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa—the country's largest cultural institution—purchased all of the cabbage patch archives citing it as 'an important part of our artistic and social history'.[19]

While this earlier work was mostly done in the deserts of the American west, the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s saw works moving into the public landscape. Artists like Robert Morris began engaging county departments and public arts commissions to create works in public spaces such as an abandoned gravel pit.[20] Herbert Bayer used a similar approach and was selected to create his Mill Creek Canyon Earthworks in 1982. The project served functions such as erosion control, a place to serve as a reservoir during high rain periods, and a 2.5 acre park during dry seasons.[21] Lucy Lippard's groundbreaking book, on the parallel between contemporary land art and prehistoric sites, examined the ways in which these prehistoric cultures, forms and images have "overlaid" onto the work of contemporary artists working with the land and natural systems.[14]

The expanding term of environmental art also encompasses the scope of the urban landscape. Agnes Denes created a work in downtown Manhattan Wheatfield - A Confrontation (1982) in which she planted a field of wheat on the two-acre site of a landfill covered with urban detritus and rubble. The site is now Battery Park City and the World Financial Center: morphing from ecologic power to economic power.

Alan Sonfist introduced the key environmentalist idea of bringing nature back into the urban environment with his first historical Time Landscape sculpture, proposed to New York City in 1965, and visible to this day at the corner of Houston and LaGuardia in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Today Sonfist is joining forces with the broad enthusiasm for environmental and green issues among public authorities and private citizens to propose a network of such sites across the metropolitan area, which will raise consciousness of the key role that nature will play in the challenges of the 21st century. The sacredness of nature and the natural environment is often evident in the work of Environmental Artists.

Just as the earthworks in the deserts of the west grew out of notions of landscape painting, the growth of public art stimulated artists to engage the urban landscape as another environment and also as a platform to engage ideas and concepts about the environment to a larger audience. "Many environmental artists now desire not merely an audience for their work but a public, with whom they can correspond about the meaning and purpose of their art."[22] Andrea Polli's installation Particle Falls made particulate matter in the air visible in a way that passersby could see.[23] For HighWaterLine Eve Mosher and others walked through neighborhoods in at-risk cities such as New York City and Miami, marking the projected flood damage which could occur as a result of climate change and talking with residents about what they were doing.[24][25]

Superstorm Sandy initiated numerous artists responses to New York City's forgotten waterfront and historical waterways. The exhibition, Silent Beaches, Untold Stories: New York City's Forgotten Waterfront, curated by St. John's University professor, Elizabeth Alpert, presented a range of artists approaches to the urban environment and complex ecological systems of New York City.[26]

EcoArt

Ecological art a.k.a. EcoArt is an artistic practice or discipline proposing paradigms sustainable with the life forms and resources of our planet.[27] It is composed of artists, scientists, philosophers and activists who are devoted to the practices of ecological art.[28] Historical precedents include Earthworks, Land Art, and landscape painting/photography. EcoArt is distinguished by a focus on systems and interrelationships within our environment: the ecological, geographic, political, biological and cultural.[29] Ecoart creates awareness, stimulates dialogue, changes human behavior towards other species, and encourages the long-term respect for the natural systems we coexist with. It manifests as socially engaged, activist, community-based restorative or interventionist art. Ecological artist, Aviva Rahmani believes that "Ecological Art is an art practice, often in collaboration with scientists, city planners, architects and others, that results in direct intervention in environmental degradation. Often, the artist is the lead agent in that practice."[30][31] There are numerous approaches to EcoArt including but not limited to:

• Representational Artworks - revealing information and conditions primarily through image-making and object-making with the intention of stimulating dialogue.

• Remediation Projects that reclaim or restore polluted and disrupted environments – these artists often work with environmental scientists, landscape architects and urban planners[32]

• Activist Projects that engage, inform, energize and activate change of behaviors and/or public policy.[33]

• Social Sculptures – socially engaged, time-based artwork that involves communities in monitoring their landscapes and taking a participatory role in sustainable practices and lifestyles.

• EcoPoetic approaches that initiate a re-envisioning and re-enchantment with the natural world, inspiring healing and co-existence with other species.

• Direct Encounters – artworks that bring into play natural phenomena such as water, weather, sunlight, plants, etc.[34]

• Didactic or Pedagogical Works that share information about environmental injustice and ecological problems such as water and soil pollution and health hazards.

• Lived-and-relational Aesthetics involving sustainable, off-the-grid, permaculture existences.[35]

Contributions by women in the area of EcoArt are significant, many are cataloged in WEAD, Women Environmental Artists Directory founded in 1995 by Jo Hanson, Susan Leibovitz Steinman and Estelle Akamine.[36]

EcoArt definition: There is discussion and debate among Ecological Artists, if Ecological Art or EcoArt, should be considered a discrete discipline within the Arts, distinct from Environmental Art. A current definition of Ecological Art, drafted collectively by the EcoArtNetwork is "Ecological Art is an art practice that embraces an ethic of social justice in both its content and form/materials. EcoArt is created to inspire caring and respect, stimulate dialogue, and encourage the long-term flourishing of the social and natural environments in which we live. It commonly manifests as socially engaged, activist, community-based restorative or interventionist art.[37] "Artists considered to be working within this field subscribe generally to one or more of the following principles:

• Focus on the web of interrelationships in our environment—on the physical, biological, cultural, political, and historical aspects of ecological systems.

• Create works that employ natural materials or engage with environmental forces such as wind, water, or sunlight.

• Reclaim, restore, and remediate damaged environments.

• Inform the public about ecological dynamics and the environmental problems we face.

• Revision ecological relationships, creatively proposing new possibilities for coexistence, sustainability, and healing.[38]

Considering environmental impact

Within environmental art, a crucial distinction can be made between environmental artists who do not consider the possible damage to the environment that their artwork may incur, and those whose intent is to cause no harm to nature. For example, despite its aesthetic merits, the American artist Robert Smithson’s celebrated sculpture Spiral Jetty (1969) inflicted permanent damage upon the landscape he worked with, using a bulldozer to scrape and cut the land, with the spiral itself impinging upon the lake. Similarly, criticism was raised against the European sculptor Christo when he temporarily wrapped the coastline at Little Bay, south of Sydney, Australia, in 1969. Conservationists' comments attracted international attention in environmental circles and led contemporary artists in the region to rethink the inclinations of land art and site-specific art.

Sustainable art is produced with consideration for the wider impact of the work and its reception in relationship to its environments (social, economic, biophysical, historical, and cultural). Some artists choose to minimize their potential impact, while other works involve restoring the immediate landscape to a natural state.[2]

British sculptor Richard Long has for several decades made temporary outdoor sculptural work by rearranging natural materials found on site, such as rocks, mud and branches, which will therefore have no lingering detrimental effect. Chris Drury instituted a work entitled "Medicine Wheel" which was the fruit and result of a daily meditative walk, once a day, for a calendar year. The deliverable of this work was a mandala of mosaicked found objects: nature art as process art. Crop artist Stan Herd[39] shows similar connection with and respect for the land.

Leading environmental artists such as the Dutch sculptor Herman de Vries, the Australian sculptor John Davis and the British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy similarly leave the landscape they have worked with unharmed; in some cases they have revegetated damaged land with appropriate indigenous flora in the process of making their work. In this way the work of art arises out of a sensitivity towards habitat. Perhaps the most celebrated instance of environmental art in the late 20th century was 7000 Oaks, an ecological action staged at Documenta during 1982 by Joseph Beuys, in which the artist and his assistants highlighted the condition of the local environment by planting 7000 oak trees throughout and around the city of Kassel.

Ecological awareness and transformation

Other artists, like eco-feminist artist Aviva Rahmani reflect on our human engagement with the natural world, and create ecologically informed artworks that focus on transformation or reclamation. In the last two decades significant environmentally concerned work has been made by Rosalie Gascoigne, who fashioned her serene sculptures from rubbish and junk she found discarded in rural areas. Patrice Stellest created big installations with junk, but also incorporated pertinent items collected around the world and solar energy mechanisms. John Wolseley hikes through remote regions, gathering visual and scientific data, then incorporates visual and other information into complex wall-scale works on paper. Environmental art or Green art by Washington, DC based glass sculptors Erwin Timmers and Alison Sigethy incorporates some of the least recycled building materials; structural glass. EcoArt writer and theoretician Linda Weintraub coined the term, "cycle-logical" to describe the correlation between recycling and psychology. The 21st century notion of artists' mindful engagement with their materials harkens back to paleolithic midden piles of discarded pottery and metals from ancient civilizations.[40] Weintraub cites the work of MacArthur Fellow Sarah Sze who recycles, reuses, and refurbishes detritus from the waste stream into elegant sprawling installations. Her self-reflective work draws our attention to our own cluttered lives and connection to consumer culture.[41][42] Brigitte Hitschler's Energy field drew power for 400 red diodes from the to-be-reclaimed potash slag heap upon which they were installed, using art and science to reveal hidden material culture.[43] Ecological artist and activist, Beverly Naidus, creates installations that address environmental crises, nuclear legacy issues, and creates works on paper that envision transformation.[44] Her community-based permaculture project, Eden Reframed remediates degraded soil using phytoremediation and mushrooms resulting in a public place to grow and harvest medicinal plants and edible plants. Naidus is an educator having taught at the University of Washington, Tacoma for over ten years, where she created the Interdisciplinary Studio Arts in Community curriculum merging art with ecology and socially engaged practices.[45] Naidus's book, Arts for Change: Teaching Outside the Frame is a resource for teachers, activists and artists.[46][47] Sculptor and installation artist Erika Wanenmacher was inspired by Tony Price in her development of works addressing creativity, mythology, and New Mexico’s nuclear presence.[48] Various artists, including Daniele Del Nero, have worked in different ways using living mold as an artistic element.[49][50]

Renewable energy sculpture

Renewable energy sculpture is another recent development in environmental art. In response to the growing concern about global climate change, artists are designing explicit interventions at a functional level, merging aesthetical responses with the functional properties of energy generation or saving. Andrea Polli's Queensbridge Wind Power Project is an example of experimental architecture, incorporating wind turbines into a bridge's structure to recreate aspects of the original design as well as lighting the bridge and neighbouring areas.[51] Ralf Sander's public sculpture, the World Saving Machine, used solar energy to create snow and ice outside the Seoul Museum of Art in the hot Korean summer.[52][53] Practitioners of this emerging area often work according to ecologically informed ethical and practical codes that conform to Ecodesign criteria.

See also

- Arte povera

- BioArt

- crop art

- Ecofeminist art

- Ecological art

- Ecovention

- Environmental movement

- Environmental sculpture

- Environmentalism

- Greenmuseum.org

- Land art

- Land Arts of the American West

- Natural World Museum

- Process art

- Site-specific art

- Sustainable art

- Teaneck Creek Conservancy

- Trashion

- Waterfire

- ART/MEDIA

- Urban acupuncture in art

References

- 1 2 Bower, Sam (2010). "A Profusion of Terms". greenmuseum.org. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Steinman, Susan. "WEAD, Women Environmental Artists Directory". WEAD, Women Environmental Artists Directory. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ Kastner, J. and Wallis, B. Eds. (1998) Land and Environmental Art. London: Phaidon Press.

- ↑

- Gablik, S. (1984) Has Modernism Failed? New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Gablik, S. (1992) The Reenchantment of Art. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Matilsky, B., (1992) Fragile Ecologies: Contemporary Artists Interpretations and Solutions, New York, NY: Rizolli International Publications Inc.

- ↑ Weintraub, Linda. "Untangling Eco from Enviro". Artnow Publications. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "The Landscape in Art: Nature in the Crosshairs of an Age-Old Debate - ARTES MAGAZINE". ARTES MAGAZINE. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Thornes, John E. (2008). "A Rough Guide to Environmental Art" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 33: 391–411 (395). doi:10.1146/annurev.environ.31.042605.134920.

- ↑ House, John (1986). Monet: Nature into Art. London: Yale Univ. Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-300-03785-6.

- ↑ "Painting Climate Change: An Interview with Artist Diane Burko About Her Show 'The Politics of Snow'". TheScientist. March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Arntzenius, Linda (September 5, 2013). "Diane Burko's Polar Images Document Climate Change". Town Topics.

- ↑ Tranberg, Dan (December 1, 2010). "Alexis Rockman". Art in America. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Kastner, Jeffrey and Wallis, Brian (1998) Land and Environmental Art, London: Phaidon Press, p. 23, ISBN 0-7148-3514-5

- ↑ Beardsley, p. 7

- 1 2 Lippard, Lucy (1995). Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory. London: The New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-238-0.

- ↑ Wolfgang Becker, Sculpture Nature, Centre d'Arts Plastiques Contemporain, Bordeaux, 1980

- ↑ [https://books.google.com/books/about/L_espace_de_profil.html?id=PAlPAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y Space in profile/ L'espace de profil,

- ↑ Piotr Kowalski, by Jean-Christophe Bailly : Éditions Hazan, Paris, 1988,

- ↑ Book Analysis of a process over time - 2007 - ISBN 980-6472-21-7

- ↑ Farrar, Sarah (November 2, 2012), ‘Vacant lot of cabbages’ documentation enters Te Papa’s archives, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- ↑ Beardsley, p. 90

- ↑ Beardsley, p. 94

- ↑ Beardsley, p. 127

- ↑ "Particle Falls, Public Art by Andrea Polli". Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ Doan, Abigail (2013-11-26). "HighWaterLine: Visualizing Climate Change with Artist Eve Mosher". The Wild Magazine. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ↑ Kolbert, Elizabeth (2012-11-12). "Crossing the Line". The New Yorker. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ↑ Trapasso, Clare (September 6, 2013). "St. John's University exhibit sheds light on forgotten waterfront". New York Daily News. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Wildy, Jade. "Progressions in Ecofeminist Art: The Changing Focus of Women in Environmental Art". International Journal of the Arts and Society. The Arts Collection. 6 (1): 53–66.

- ↑ Weintraub, Linda (2006). Eco-Centric Topics: Pioneering Themes for Eco-Art (PDF). New York: Artnow Publications: Avant-Guardians: Textlets in Art and Ecology.

- ↑ Weintraub, Linda (2007). EnvironMentalities: Twenty-Two Approaches to Eco-Art (PDF). New York: Artnow Publications, Avan-Guardians: Texlets in Art and Ecology.

- ↑ Rahmani, Aviva (Spring–Summer 2013). "Triggering Change: A Call to Action" (PDF). Public Art Review (48): 23. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ http://www.sfeap.org

- ↑ Rahmani, Aviva; Schroeder, Paul C.; Boudreau, Paul R.; Brehme, Chris E.W.; Boyce, Andrew M.; Evans, Alison J. (2001). "The Gulf of Maine Environmental Information Exchange:participation, observation, conversation". Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 28 (6): 865–887. doi:10.1068/b2749t.

- ↑ Stringfellow, Kim (2003). "Safe As Mother's Milk: The Hanford Project". ACM Digital Library. Siggraph '03 Proceedings. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Dionisio, Jennifer. "Calendar of Rain". Chemical Heritage Foundation.

- ↑ Santoro, Alyce. "We are the instant & efficient & comprehensive Synergetic Omni Solution". 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Hanson, Jo, Leibovitz Steinman, Susan and Akamine, Estelle. "WEAD, Women Environmental Artists Directory". WEAD, Women Environmental Artists Directory.

- ↑ Kagan, Sacha (2014). The practice of ecological art. [plastik] 4 . Available online at: http://art-science.univ-paris1.fr/plastik/document.php?id=866. ISSN 2101-0323.

- ↑ "ISE's Beverly Naidus publishes "Arts for Change"". Institute for Social Ecology. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Herd, Stan (1994) Crop Art and Other Earthworks", New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., ISBN 0810925753

- ↑ Weintraub, Linda, with Shuckmann, Skip (2007). Cycle-Logical Art: Recycling Matters for Eco-Art. New York: Artnow Publications: Avant-Guardians Textlets on Art and Ecology. ISBN 0-9777421-5-6.

- ↑ Sze, Sarah. "Sarah Sze Selected Exhibitions". Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ Sze, Sarah (May 30, 2013). "At Venice Biennale, Sara Sze's 'Triple Point'". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ Hitschler, Brigitte (2003). "Energy Field" (PDF). HYLE – International Journal for Philosophy of Chemistry. Chemistry in Art - A Virtual Art Exhibition Jointly Published with the Special Issue on "Aesthetics and Visualization in Chemistry". Karlsruhe, Germany. 9 (3): 16. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ "Beverly Naidus". WEAD Women Environmental Artist Directory. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Naidus, Beverly (2007). "Profile: Beverly Naidus's Feminist Activist Art Pedagogy: Unleashed and Engaged". NWSA Journal. 19 (1): 137–155. doi:10.2979/nws.2007.19.1.137. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Miles, Malcom (2005). Outside the Frame: Teaching Socially Engaged Art, New Practices - New Pedagogies. New York/London: Routledge. ISBN 1134225156.

- ↑ http://www.newvillagepress.net/author/?fa=ShowAuthor&Person_ID=4

- ↑ Rutherford, James (2004). Tony Price, atomic art. Albuquerque, NM: Lithexcel. ISBN 978-0967510675. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ Liboiron, Max. "The Art of Mould". Discard Studies. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ http://slimoco.ning.com/, retrieved 27 July 2015

- ↑ Polli, Andrea. "The Queensbridge Wind Power Project". Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ Obrist, Volker (2013-08-06). "Ralf Sander's World Saving Machine Uses Solar Energy to Create Ice!". Inhabitat. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ "Projects". Wind Saving Machine. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

Bibliography

- Beardsley, John (1998). Earthworks and Beyond: Contemporary Art in the Landscape. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 0-89659-963-9.

Further reading

- Catalano, Gary (1985). An Intimate Australia : The Landscape & Recent Australian Art. Sydney, NSW: Hale & Iremonger. p. 112p. ISBN 0-86806-126-3.

- Gooding, Mel (2002). Song of the Earth: European Artists and the Landscape. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 167p. ISBN 0-500-51016-4.

- Grande, John (1994). Balance: Art and Nature. London: Black Rose Books. ISBN 1-55164-234-4.

- Grande, John (2004). Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists. New York. ISBN 0-7914-6194-7.

- Kagan, Sacha (2011). Art and Sustainability: Connecting Patterns for a Culture of Complexity. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8376-1803-7.

- Sonfist, Alan (2004). Nature: The End of Art. Florence, Italy: Gli Ori,Dist. Thames & Hudson. p. 280p. ISBN 0-615-12533-6.

- Wildy, Jade (2011). Shades of Green (Thesis). Adelaide: University of Adelaide. External link in

|title=(help)

External links

- contingent ecologies

- greenmuseum

- ecoartnetwork

- The South Florida Environmental Art Project (SFEAP)

- ecoartspace

- EarthArtists.org – listings of Earth, Land, Environmental and Eco-artists.

- Aspen Institute – Energy and Environment Awards

- List of Environmental Art Definitions

- art + environment

- Some artist examples

- Center for Economic and Environmental Development (CEED) Arts & Environment Initiative

- United Nations Art for the Environment Program

- Greenmuseum.org

- crosshairs-of-an-age-old-debate/ Artes Magazine (On line arts journal) 16 November 2010