Eniwa, Hokkaido

| Eniwa 恵庭市 | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Eniwa | ||

|

| ||

| ||

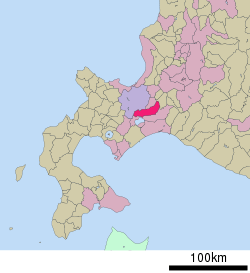

Location of Eniwa in Hokkaido (Ishikari Subprefecture) | ||

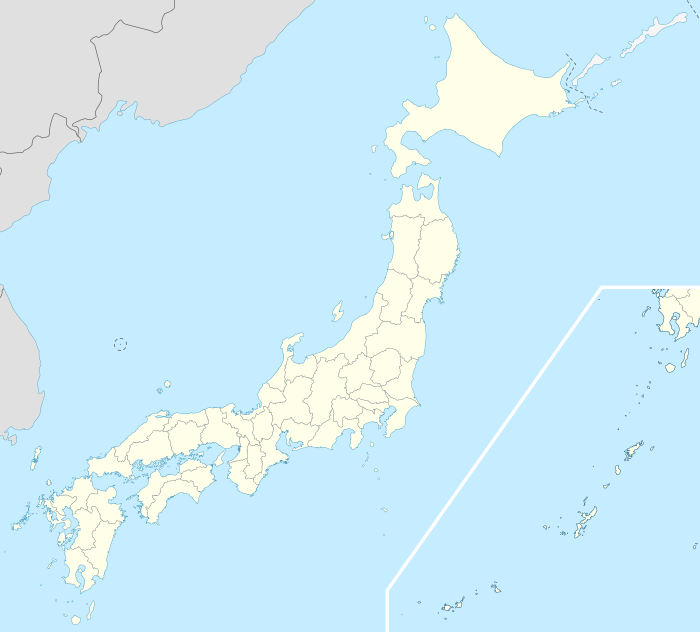

Eniwa Location in Japan | ||

| Coordinates: 42°53′N 141°35′E / 42.883°N 141.583°ECoordinates: 42°53′N 141°35′E / 42.883°N 141.583°E | ||

| Country | Japan | |

| Region | Hokkaido | |

| Prefecture | Hokkaido (Ishikari Subprefecture) | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Yutaka Harada (since November 2009) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 294.87 km2 (113.85 sq mi) | |

| Population (October 2013) | ||

| • Total | 68,883 | |

| • Density | 233.60/km2 (605.0/sq mi) | |

| Symbols | ||

| • Tree | Japanese Yew | |

| • Flower | Lily of the Valley | |

| • Bird | Kingfisher | |

| • Others | Ebisu kabocha pumpkin | |

| Time zone | Japan Standard Time (UTC+9) | |

| City hall address |

1, Kyōmachi, Eniwa-shi, Hokkaido 061-1498 | |

| Website |

www | |

Eniwa (恵庭市 Eniwa-shi) (Japanese pronunciation: [eniw͍a]) is a city in Ishikari Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan. It is on the Ishikari plain, 8 km north of Chitose and 26 km south of the prefectural capital Sapporo. It is reached through route 36 and the Chitose Railway Line. The town is separated into three major areas: Eniwa in the south, Megumino in the center, and Shimamatsu in the north.

Many farms are located around Eniwa, and the town has many manufacturing businesses, including the Sapporo Brewery Hokkaido factory. There are three Japan Ground Self-Defense Force camps in the city.

Eniwa's 2012 population of 68,883 makes it the fourth largest city in the Ishikari Subprefecture and the 13th largest in Hokkaido.

Etymology

The town's name is taken from the nearby Mount Eniwa, in the Shikotsu-Tōya National Park. The name in Ainu, e-en-iwa (エエンイワ), means "sharp mountain."[1] The name was transliterated into Japanese ateji to mean blessed garden. The Japanese transliteration was chosen because of the homonyms niwa (庭, "garden") and niwa (二輪, "two rings"), the later referring to the two rivers that pass through the city, the Shimamatsu River and the Izari River, as well as the "blessings" (e (恵)) between the two rivers.[2]

History

The first known settlement of Eniwa was in the Initial Jōmon period in 7000 BC, at the Karinba Ruins (カリンバ遺跡 Karinba Iseki).[3][4] The settlement received a surge of people in 2000 B,[5] and continued being settled for many years. Many artifacts have been found, including lacquered combs, beads, earthenware and stone accessories.[3] Historical Satsumon culture (700–1200 CE) graves dating have been found around Eniwa, at the Moizari Kofun Site (茂漁古墳群 Moizari kofun-gun).[6] The style is similar to those at the Ebetsu Kofun Site and northern Tōhoku historic graves. During the Ainu settlement period (1200 CE until the Meiji era), there is historical evidence for settlements in the villages and further away on the plains.[3]

After the Matsumae clan settled on the southern tip of Hokkaido in 1590, they traded goods with the Ainu who lived in the area. In the Edo period, one of the 13 trading locations across the Ishikari plain was Shuma-mappu Location (シュママップ場所 Shumamappu Basho) (Ainu: Shuma-o-mappu (シュマ・オ・マップ)), which corresponds to the modern-day Shimamatsu River basin. The trading area was active until the end of the Edo era. Early Japanese contact with the area included in 1755, when jezo spruce trees were harvested along the Izari river, and in 1805, when the river was farmed for salmon and trout.[5]

In 1857, the Hakodate magistrate decreed that a road between Otaru and Chitose be developed, leading to the development of the Ishikari Plain.[5] When Hokkaido became a part of Japan in the early Meiji period, the area around Eniwa was incorporated into Iburi Province in 1869.[7]

Settlers from Kōchi Prefecture initially settled in Eniwa in 1870 in two villages: Izari Village (漁村 Izari-mura) in the south and Shimamatsu Village (島松村 Shimamatsu-mura) in the north.[2] In 1873, the Sapporo Highway (札幌本道 Sapporo Hondō), the a road linking Hakodate with Sapporo was completed, and it was built through both villages. In 1873, rice farming started in Shimamatsu, as well as the first postal service.[5]

In 1880, the Chitose town hall began administering five surrounding villages to Chitose, including Izari and Shimamatsu.[8] In 1886, 65 families from Waki, Yamaguchi and Iwakuni, Yamaguchi moved to the shores of the Izari river, which greatly increased the size of Izari.[2] A year later, the Izari town hall was built, meaning Chitose no longer administered Izari or Shimamatsu.[2][8] At this point, Eniwa had grown to 572 residents, and the first elementary school was opened.[2] Shinto shrines were constructed in 1901: Toyosaka Shrine in Izari and Shimamatsu Shrine. The Buddhist temple Ten'yū-ji's main building was constructed in 1904.

In 1906, Izari and Shimamatsu were merged to form Eniwa Village (恵庭村 Eniwa-mura), a second class municipality.[2] The village also administered Hiroshima Village; in 1943 the village seceded. In 1922, the village received electricity, after the Izari River was used for hydroelectric power.[5] By 1923, the town had grown enough to become a first class municipality. Eniwa was first connected to by rail in 1926, after the Sapporo Line (now known as the Chitose Line) was completed, and Eniwa Station and Shimamatsu Station were opened.[5]

In the 1930s, Eniwa became a site for mining gold and silver. In 1935, a small-scale private mine called the Kōryū Mine (光竜鉱山 Kōryū Kōzan) was opened in 1935 and run by the Fujita company.[9] In 1939, the nationally run Eniwa Gold Mine (恵庭鉱山 Eniwa Kōzan) opened. A mining town to the north-northwest of Mount Eniwa was constructed, and Kōryū Mine was expanded. The town featured around 40 five-family apartments and additional buildings for administration and amenities, however, no restaurants or entertainment areas were constructed.[10] Two elementary schools were operated for the area. Both mines were closed in 1943, due to the Order for Gold Mine Consolidation.[11] By the end of the Eniwa Mine's operations, a total of 700 kg of gold and 3,500 kg of silver had been mined.[12] The mines and buildings were dismantled, though the Kōryū Mine was reopened in 1949 by Yutani Mining.[9]

After the Occupation of Japan beginning in 1945, many agricultural reforms were undertaken that made the farms around Eniwa more prosperous.[5] In September 1950, a military camp for training police personnel was built in Kashiwagi.[5][13] In 1951, Company C, 52d Infantry Regiment (Anti-Tank) of the United States Army held military practices at the camp.[5][14] When the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force's Northern Army was established in 1952, they took over running the camp and established the South Eniwa Camp in 1952.[15]

By 1951, the village's population was significant enough to be upgraded to a town.[2] In 1970 after the town had 34,500 residents, it was upgraded to Eniwa City, after a piece of regional legislation allowed Eniwa, Noboribetsu and later Date to become cities.[2] In 1979, part of the farmland between Eniwa and Shimamatsu was developed into Megumino, a new suburb of the city. By 1982, the Megumino Station was built, along with the Ito-Yokado shopping center and the Megumino Elementary School.

In 1987, residents exceeded 50,000.[2] The Sapporo Brewery Hokkaido factory was built in the south of Eniwa in 1989,[16] and a dedicated train station, the Sapporo Beer Teien Station was built in 1990. In 1993, residents in Eniwa exceeded 60,000.[2]

In 2006, Eniwa's first community radio station began broadcast. It was originally called FM Pumpkin (FMパンキン), but the name was changed to E-Niwa in 2010.[5]

In April 2013, construction began on East Garden Megumino (イーストガーデン恵み野 Īsuto Gāden Megumino), a 4.6 hectare housing development in east Megumino. The first houses were completed in May 2013, with the entire area expected to be completed in 2015.[17] The development of 25 hectares west of Megumino Station is being planned. Development consent was given in July 2011.[18]

Demographics

| Population census | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1955 | 19,900 | — |

| 1960 | 29,575 | +8.25% |

| 1965 | 31,240 | +1.10% |

| 1970 | 34,449 | +1.97% |

| 1975 | 39,884 | +2.97% |

| 1980 | 42,911 | +1.47% |

| 1985 | 48,305 | +2.40% |

| 1990 | 55,615 | +2.86% |

| 1995 | 62,351 | +2.31% |

| 2000 | 65,239 | +0.91% |

| 2005 | 67,614 | +0.72% |

| 2010 | 69,334 | +0.50% |

| Source: [19] | ||

As of October 2013, the city has an estimated population of 68,883 residents, with 31,005 households and the density of 233.60 persons per km². 51% of the population is female.[20] Eniwa's population is 99.7% Japanese, with the remaining 0.3% being foreign residents.[21] 13.8% of residents are under 15 years of age, and the workforce comprises 64.4% of residents. 21.8% of people are over age 65. In the 2012 population records, 22 residents are listed as centenarians.[21]

The bulk of the population, 68%, lives in central Eniwa, while 17.5% live in Megumino and 13.2% live in Shimamatsu. The remainder 1.3% of Eniwa residents live in the surrounding farmland.[20]

Geography and climate

Eniwa is on the Ishikari Plain, amongst farmland. The town is 8 km from Chitose (and the New Chitose Airport), and to the north is Kitahiroshima City. 26 km north of Eniwa is Sapporo, the largest city and prefectural capital of Hokkaido. All of these cities are connected by the Chitose Line railway and by the Japan National Route 36. The town is on the Izari River and the Shimamatsu River.[2]

The area administered to by Eniwa extends north to the Shimamatsu river and stops at the border to Naganuma township in Sorachi Subprefecture. Eniwa borders Chitose city along its south border, with the cities being separated by as little as 750 m in some places. To the west of Eniwa is the Shikotsu-Tōya National Park. Eight mountains in the park are considered a part of Eniwa, including Mount Izari and Mount Soranuma. In the area is the hydroelectric Izarigawa Dam that dams the Izari river.

The city of Eniwa is separated into three major areas: Eniwa in the south, Megumino (恵み野) in the center and Shimamatsu in the north. Shimamatsu is separated from Eniwa and Megumino by approximately 300 meters.

Winters in Eniwa are colder than the surrounding areas, due to the town being inland. The average daily low temperature is between 5-6 degrees lower than Sapporo, 26 km to the north near the Sea of Japan, and 4-5 degrees lower than in Tomakomai, 28 km to the south on the coast of the Pacific Ocean. Summers are slightly more milder than in Sapporo.[22]

| Climate data for Eniwa, Japan (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.8 (82) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.3 (93.7) |

31.8 (89.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.9 (37.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.0 (68) |

23.2 (73.8) |

25.0 (77) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

1.1 (34) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −13.2 (8.2) |

−12.8 (9) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

0.1 (32.2) |

5.4 (41.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.1 (52) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

1.7 (35.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.8 (−16.2) |

−26.9 (−16.4) |

−21.1 (−6) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−26.9 (−16.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.9 (2.24) |

54.1 (2.13) |

52.1 (2.051) |

62.2 (2.449) |

78.6 (3.094) |

64.1 (2.524) |

101.3 (3.988) |

167.3 (6.587) |

150.6 (5.929) |

105.3 (4.146) |

85.3 (3.358) |

66.7 (2.626) |

1,044.3 (41.114) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 168 (66.1) |

159 (62.6) |

102 (40.2) |

11 (4.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

12 (4.7) |

124 (48.8) |

576 (226.8) |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[22] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Traditionally, Eniwa's economy was based around farming, with the first major rice farms created in 1873.[5] Eniwa has two main crops: flowers and rice.[23] 3,800ha of land are dedicated to flowers, most of which are cut flowers. 2,700 ha of land are dedicated to rice farming, mostly ley farming, though paddy field rice exists.[23] Rice in Eniwa is generally made up of the Yume Pirika, Nanatsu Boshi, Oborozuki and Fukkurinko.[24]

Eniwa also grows many vegetables. Vegetables with 100 ha or more dedicated space include wheat, soybeans, sugar beet, potatoes and daikon (Japanese radish). Other farmed vegetables include ebisu kabocha pumpkins, carrots, adzuki beans and cabbages.[23] The ebisu kabocha is the city vegetable. Pumpkin-flavored soft serve, manjū and soup can be bought at the Flower Road Eniwa roadside station.[25]

In the Heisei era, manufacturing has increasingly become an important industry. In 1989, an area in southern Eniwa became dedicated to manufacture, called the Eniwa Techno Park (恵庭テクノパーク Eniwa Tekuno Pāku).[5] In the same year, the Sapporo Brewery Hokkaido factory was built. It deals with 120 million liters of beer per year.[16][26] There are many food production factories are in Eniwa, including ones for Sanmaruko, the restaurant chain Tonden, oden producer Horikawa, Hoshio Milk, Yamazaki Baking, Kibun Foods and Robapan. Morinaga Milk Industry built its Sapporo Factory in Eniwa in 1961; in April 2013 it halted all manufacturing there, leaving the site as a delivery depot.[27]

There are mechanical factories for Sanwa Holdings, MSK Farm Machinery, Mitsubishi's customized machinery division and Oji Paper.

Three camps for the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force's Northern Army are in Eniwa — Camp Shimamatsu, Camp Kita Eniwa, and Camp Minami Eniwa — where the Northern Army performs military exercises, including the 1st Tank Group's tank practice.

Religion

There are a variety of Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines and Christian churches in Eniwa. Most of the institutions were established in the Meiji period. The most recent Shinto shrine was built in 1908.

There are seven Buddhist temples in Eniwa. The largest is Ten'yū-ji, an Otani-ha temple established in 1886.[28] Daian-ji was initially established as a terakoya school for the children of Eniwa in 1887, but grew to be a temple in 1911.[29] The Eniwa Buddhist temples follow a variety of schools. Two of the temples are Otani-ha, two are Hongan-ji, Kōryū-ji is a Kompira worshiping Kōyasan Shingon-shū temple, Daian-ji is Sōtō and Myōshō-ji is Nichiren Shū.

There are four Shinto shrines around Eniwa. Toyosaka Shrine was first established in 1874 as an area dedicated to Inari Ōkami, with a small shrine for Ōkuninushi built at the site in 1891.[30] A second shrine, built to accommodate settlers from Toyama and Ishikawa.[31] Shimamatsu Shrine was established in 1901 from donations from the people who lived in Shimamatsu.[32] The fourth, Kashiwagi Shrine, was established in 1908. Much of the shrine was demolished in 1982 due to dilapidation.[33] In Eniwa, there are six Shinto gods who have been enshrined: Toyouke-Ōmikami (at Toyosaka and Shimamatsu), Ōkuninushi (at Toyosaka), Amenominakanushi (at Kashiwagi) and Amaterasu, Inari Ōkami and Kasuga Ōkami at Eniwa Shrine.

There are three Christian churches in Eniwa, the Catholic Eniwa Parish, Eniwa Evangelical Christian Church and the Eniwa Evangelical Lutheran church. In addition, there is a Jehovah's Witness church, as well as a church for the Chitose and Eniwa ward of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Parks and recreation

Eniwa has five public parks: Eniwa Park, Nakajima Park, Furusato Park, Megumino Central Park and Technopark Central Park. The parks are mostly around central and southern Eniwa.[34] The largest, Eniwa Park, is 411,000m². In addition, the land around the banks of the Izari River is considered urban open space. Parks in Eniwa mostly consist of open spaces and woodland, though several feature sporting facilities, such as Nakajima Park's jogging track.

In 2006, an agricultural theme park called Ecorin Village was built in Eniwa. At the gardening center of the theme park is a greenhouse housing Tomato no Mori (とまとの森, "Tomato Forest"), which in November 2013 was awarded the Guinness World Records award for the largest tomato plant in the world, measuring 85.46m2 at the time.[35]

Within the urban borders of Eniwa are several park golf grounds, a sport created in Hokkaido. Outside of the city, the Eniwa Country Club features three nine-hole golf courses.[36]

In the Shikotsu-Tōya National Park to the west, many of the mountains such as Mount Izari and Mount Soranuma feature walking trails to their summits. The man-made Lake Eniwa (えにわ湖 Eniwa-ko) lake is behind the Izari Dam in the national park,.

Education

Eniwa has two public high schools, five junior high schools, and eight elementary schools. In 2012, the city had 3,935 students enrolled at elementary schools and 2,079 at junior high schools.[37] In 2008, 300 students were enrolled at Eniwa North High School and 200 at Eniwa South High School.[38][39]

Eniwa's first school was opened in 1887, when Buddhist priest Kyūzō Nakayama established a terakoya for the children of Eniwa.[29] In 1897, the temple school was moved and became a public school, Eniwa Elementary School.[40] Three more elementary schools were opened in the Meiji period. By the early 1940s, Eniwa had eight elementary schools. In 1947, four new junior high schools were created, later amalgamating into two by 1964. The two high schools were opened in 1951. In the 1960s and 1970s, five elementary schools and one junior high school were closed or merged. With the building of Megumino in the late 1970s and increasing growth in the city, three new junior high schools and six new elementary schools were built between 1970 and 1991.[5]

Eniwa has one university and three vocational schools. Hokkaido Bunkyo University's main campus is in Eniwa. The university has two departments, foreign languages and health sciences.[41] The three vocational schools are in Megumino. The largest, the Hokkaido High-Technology College, is a multi-discipline school, with four faculties: technology, medicine, education and recovery/sports science.[42] The Hokkaido Eco Communication College is a veterinary school,[43] and the Nihon Fukushi Rehabilitation Gakuin is a physical medicine and rehabilitation school. In addition to these, Kinki University has its Hokkaido seminar house for natural resource research in Eniwa.

Transportation

Eniwa is connected to the Hokkaido Railway network on the Chitose Line. There are four train stations (from north to south): Shimamatsu Station, Megumino Station and Eniwa Station, as well as the electronically manned Sapporo Beer Teien Station. The Eniwa Station is a designated stop for Rapid Airport trains, though not a stop for limited express trains such as the Super Ōzora or the Super Tokachi.

Japan National Route 36 and Japan National Route 453 run through Eniwa. There are two toll express roads through Eniwa, the Hokkaidō Expressway and the Dōtō Expressway which begins at the Chitose-Eniwa junction. There are two bus services in Eniwa. The Hokkaido Chuo Bus transports passengers around Hokkaido and passes through Eniwa. The Eniwa Community Bus was established in 2004 and circuits around Eniwa.[5]

Eniwa is serviced by the New Chitose Airport for air travel, 15 km away. It is an international airport, with destinations mainly in Asia such as Seoul, Shanghai and Taipei. However, the bulk of its traffic is Japanese domestic travelers.

Community work

In the spring and summer, community organisations plant flowers around the city's public gardens, leading to the moniker 'Gardening Town' (ガーデニングのまち gādeningu no machi).[2]

Sister cities

Eniwa has two sister cities:[2]

Waki, Yamaguchi (established 1979)

Waki, Yamaguchi (established 1979) Timaru, New Zealand (established 2008)

Timaru, New Zealand (established 2008)

External links

![]() Media related to Eniwa, Hokkaidō at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eniwa, Hokkaidō at Wikimedia Commons

- (Japanese) Official homepage

- Official homepage

References

- ↑ アイヌ語地名リスト [Ainu Language Place Name List] (PDF) (in Japanese). Office of Ainu Measures Promotion, Department of Environment and Lifestyle, Hokkaido Government. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 恵庭市の概要 [An Outline of Eniwa City] (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 カリンバ遺跡パンフレット [Karinba Ruins Pamphlet] (PDF) (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ↑ カリンバ遺跡 [Karinba Ruins] (in Japanese). The Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 恵庭歴史年表 [Eniwa History Timeline] (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ↑ Kono, Hiromichi (December 1959). "Chōshi (鑷子)" [Tweezers]. Utari (ウタリ), Hokkaido Gakugei University Archaeology Researchers Newsletter 36 (in Japanese). Sapporo, Hokkaido: Hokkaido Gakugei University. 2 (15).

- ↑ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric; Roth, Käthe (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01753-6.

- 1 2 『新千歳市史』編さんだより 志古津 過去からのメッセージ 第6号 [Shikotsu - message from the past. (from the New Chitose City History) (issue number 6)] (PDF) (in Japanese). City of Chitose. July 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- 1 2 Watanabe, Shigeru (1979). 恵庭市史 [Eniwa City History]. Eniwa, Japan: Eniwa City Office.

- ↑ Asada, Masahiro (1999). 北海道金鉱山史研究 [Hokkaido Gold Mine History Research]. Sapporo, Japan: Hokkaido University Press. ISBN 4-8329-6021-0.

- ↑ 千歳鉱山と恵庭鉱山、光竜鉱山 [Chitose Mine, Eniwa Mine and Koryu Mine] (in Japanese). Hokkaido Government. 2006. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ↑ 北海道の金属鉱業 [Hokkaido Metal Mining Industry]. Hokkaidō Kōgyōkai. 1952. p. 79.

- ↑ 北恵庭駐屯地 [North Eniwa Camp] (in Japanese). Japan Self Defence Force. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ Clayton, John (July 10, 1951). "Mock Battle as Much Like Real As Can be Made". Ada Evening News. Ada, Oklahoma. p. 1. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ↑ 陸上自衛隊イベント情報 [Self Defence Force Event Information] (in Japanese). Japan Self Defence Force. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- 1 2 工場という名の美術館 [An art gallery by the name of a factory] (in Japanese). Eniwa City Sightseeing Association. 2007. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ 恵庭で大規模な宅地開発 [Large-scale residential development in Eniwa] (in Japanese). Tomakomai Minpou. April 13, 2013. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ↑ 恵み野駅西口土地区画整理事業 土地区画整理組合設立の認可について [Megumino Station West Entrance Land Planning Project: Concerning the land development union approval] (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ↑ 恵庭市の人口 人口の推移口 [Eniwa City Population: population transitions] (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- 1 2 町名別人口調べ [Suburb population breakdown] (PDF) (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- 1 2 恵庭市の人口 年齢別人口 [Eniwa City Population: age breakdown] (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- 1 2 恵庭島松 [Eniwa Shimamatsu] (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. August 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- 1 2 3 第3期恵庭市農業振興計画 第3章 恵庭市農業の現状と主要課題 [The Third Eniwa City Farming Promotion Plan. Chapter 3: The current state of Eniwa farming and farmed goods] (PDF) (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ↑ 北海道への移住・定住への道!その5 恵庭産新 [The road for those moving or settling in Hokkaido! No. 5, Eniwa New Produce] (in Japanese). Eniwa Community Development Cooperative Blog. October 11, 2012. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ 今月の焦点 道と川の駅花ロードえにわ [This month's focus: Michi to Kawa no Eki Hana Road Eniwa] (PDF) (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. June 15, 2006. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ↑ 北海道工場 > 工場見学 [Hokkaido Factory: factory tours] (in Japanese). Sapporo Breweries. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ 札幌工場生産中止に関するお知らせ [Sapporo Factory Production Halt Announcement] (in Japanese). Morinaga Milk. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ↑ 天融寺の沿革 [Ten'yū-ji Development] (in Japanese). Ten'yū-ji. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- 1 2 大安寺について [About Daian-ji] (in Japanese). Daian-ji. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ↑ 豊栄神社 (恵庭市) [Toyosaka Shrine (Eniwa)] (in Japanese). Hokkaido Shrine Directory. 2003. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ 恵庭神社 (恵庭市) [Eniwa Shrine (Eniwa)] (in Japanese). Hokkaido Shrine Directory. 2003. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ 島松神社(恵庭市) [Shimamatsu Shrine (Eniwa)] (in Japanese). Hokkaido Shrine Directory. 2003. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ 柏木神社(恵庭市) [Kashiwagi Shrine (Eniwa)] (in Japanese). Hokkaido Shrine Directory. 2003. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ 公園管理業務 [Park management] (in Japanese). Eniwa City Development Co-operative. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ↑ えこりん村の「トマトの木」、ギネス記録に [Ecorin Village's Tomato Forest inducted into Guinness Book of Records] (in Japanese). Yomiuri Shimbun. November 20, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Courses". Eniwa Country Club. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ↑ 学校一覧 [Schools in brief] (in Japanese). City of Eniwa. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ 恵庭北高校(偏差値・倍率) [Eniwa North High School (statistics and specifics)] (in Japanese). Hokkaido High School Entrance Exam Lab. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ 恵庭南高校(偏差値・倍率) [Eniwa South High School (statistics and specifics)] (in Japanese). Hokkaido High School Entrance Exam Lab. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ 沿革 [History] (in Japanese). Eniwa Elementary School. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ↑ 学部・学科・大学院 [Departments, subjects and graduates] (in Japanese). Bunkyo University. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ 学科紹介 [Subject Introduction] (in Japanese). Hokkaido High-Technology College. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ 学科紹介 [Subject Introduction] (in Japanese). Hokkaido Eco Communication College. Retrieved October 30, 2012.