Endless Forms Most Beautiful (book)

| |

| Author | Sean B. Carroll |

|---|---|

| Country | USA |

| Subject | Evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) |

| Genre | Popular science |

| Publisher | W. W. Norton |

Publication date | 2005 |

| Pages | 331 |

Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo and the Making of the Animal Kingdom is a 2005 book by Sean B. Carroll. It presents a summary of the emerging field of evolutionary developmental biology and the role of toolkit genes. It has won numerous awards for science communication.

The book's argument is that evolution in animals (though no doubt similar processes occur in other organisms) proceeds mostly by modifying the way that regulatory genes, which do not code for structural proteins (such as enzymes), control embryonic development. In turn, these regulatory genes turn out to be based on a very old set of highly conserved genes which Carroll nicknames the toolkit. Almost identical sequences can be found across the animal kingdom, meaning that toolkit genes such as Hox must have evolved before the Cambrian radiation which created most of the animal body plans that exist today. These genes are used and reused, occasionally by duplication but far more often by being applied unchanged to new functions. Thus the same signal may be given at a different time in development, in a different part of the embryo, creating a different effect on the adult body. In Carroll's view, this explains how so many body forms are created with so few structural genes.

The book has been praised by critics, and called the most important popular science book since Richard Dawkins's The Blind Watchmaker.

Book

Context

The title quotes from the last sentence of Charles Darwin's 1859 The Origin of Species, in which he described the evolution of all living organisms from a common ancestor: "endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved."[1]

Contents

- Part I The Making of Animals

- 1. Animal Architecture

- Modern Forms, Ancient Designs.

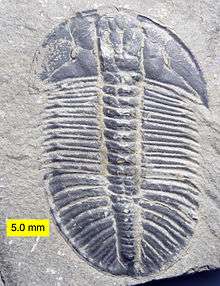

- Carroll argues that many animals have a modular design with repeated parts, as in trilobites with repeated segments, or the repeated fingers of a human hand.

- 2. Monsters, Mutants, and Master Genes

- Embryologists study how bodies develop, and the abnormalities when things go wrong, such as homeotic variants when one body part is changed into another (for instance, a fruit fly antenna becomes a leg with the Antennapedia mutant).

- 3. From E. coli to Elephants

- Carroll tells the tale of the genetic code, and the lac operon, showing that the environment and genetic switches together control gene expression. He introduces the Evo-devo gene toolkit.

- 4. Making Babies: 25,000 Genes, Some Assembly Required

- Carroll looks at how a fruit fly's embryonic development is controlled, and describes his own discoveries (back in 1994).

- 5. The Dark Matter of the Genome

- Operating Instructions for the Tool Kit

- Carroll describes how genes are switched on and off in a precisely choreographed time sequence and 3-dimensional pattern in the developing embryo, and how the logic can be modified by evolution to create different animal bodies.

.jpeg)

- Part II Fossils, Genes, and the Making of Animal Diversity

- 6. The Big Bang of Animal Evolution

- The Cambrian radiation saw an explosion in the variety of animal body plans, from flatworms and molluscs to arthropods and vertebrates. Carroll explains how shifting the pattern of Hox gene expression shaped the bodies of different types of arthropods and different types of vertebrates.

- 7. Little Bangs: Wings and Other Revolutionary Inventions

- Carroll explains how evolution goes to work within a lineage, specialising arthropod limbs from all being alike to "all of the different implements a humble crayfish carries", with (he writes) more gizmos than a Swiss Army knife.

- 8. How the Butterfly Got Its Spots

- Echoing the titles of Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories, Carroll shows how butterfly wing patterns evolved, including his discovery of the role of the Distal-less gene there, until then known in limb development. Evidently, a genetic switch could be reused for different purposes.

- 9. Paint It Black

- Carroll looks at zebra stripes, industrial melanism in the peppered moth, and the spots of big cats, all examples of the control of pattern in animals, down to molecular level.

- 10. A Beautiful Mind

- The Making of Homo sapiens.

- Carroll discusses how humans differ from other apes, and why there aren't many structural genes for the differences. Most of the changes are in genetic control, not in proteins.

- 11. Endless Forms Most Beautiful

- Carroll concludes by revisiting Darwin's Origin of Species, starting with how Darwin evolved the final paragraph of his book, leaving only these four words "completely untouched throughout all versions and editions". He shows that evo-devo is a cornerstone of a synthesis of evolution, genetics, and embryology, replacing the "Modern synthesis" of 20th century biology.

Illustrations

The book is illustrated with photographs, such as of developing fruit fly embryos dyed to show the effects of toolkit genes, and with line drawings by Jamie W. Carroll, Josh P. Klaiss and Leanne M. Olds.

Awards

- Discover magazine's Top Science Books of the Year, 2005[2]

- USA Today's Top Science Books of the Year, 2005[2]

- Banta Prize, Wisconsin Library Association, 2006[2]

- Finalist, 2005 Los Angeles Times Book Prize (Science and Technology)[2]

- Finalist, 2006 National Academy of Sciences Communication Award[2]

Reception

.png)

The evolutionary biologist Lewis Wolpert, writing in American Scientist, calls Endless Forms Most Beautiful "a beautiful and very important book." He summarizes the message of the book with the words "As Darwin's theory made clear, these multitudinous forms developed as a result of small changes in offspring and natural selection of those that were better adapted to their environment. Such variation is brought about by alterations in genes that control how cells in the developing embryo behave. Thus one cannot understand evolution without understanding its fundamental relation to development of the embryo." Wolpert notes that Carroll intended to explain evo-devo, and "has brilliantly achieved what he set out to do."[3]

Jerry A. Coyne, writing in Nature, describes the book as for the interested lay reader, and calls it "a paean to recent advances in developmental genetics, and what they may tell us about the evolutionary process." For him, the centrepiece is "the unexpected discovery that the genes that control the body plans of all bilateral animals, including worms, insects, frogs and humans, are largely identical. These are the ‘homeobox’ (Hox) genes". He calls Carroll a leader in the field and an "adept communicator", but admits to "feeling uncomfortable" when Carroll sets out his personal vision of the field "without admitting that large parts of that vision remain controversial." Coyne points out that the idea that the "‘regulatory gene’ is the locus of evolution" dates back to Roy Britten and colleagues around 1970, but was still weakly supported by observation or experiment. He grants that chimps and humans are almost 99% identical at DNA level, but points out that "humans and chimps have different amino-acid sequences in at least 55% of their proteins, a figure that rises to 95% for humans and mice. Thus we can't exclude protein-sequence evolution as an important reason why we lack whiskers and tails." He also notes that nearly half of human protein-coding genes do not have homologues in fruit flies, so one could argue the opposite of Carroll's thesis and claim that "evolution of form is very much a matter of teaching old genes to make new genes."[4]

The review in BioScience noted that the book serves as a new Just So Stories, explaining the "spots, stripes, and bumps" that had attracted Rudyard Kipling's attention in his children's stories. The review praises Carroll for tackling human evolution and covering the key concepts of what Charles Darwin called the grandeur of [the evolutionary view of] life, suggesting that "Kipling would be riveted."[5]

The science writer Peter Forbes, writing in The Guardian, calls it an "essential book" and its author "both a distinguished scientist ... and one of our great science writers."[6] The journalist Dick Pountain, writing in PC Pro magazine, argues that Endless Forms Most Beautiful is the most important popular science book since Richard Dawkins's The Blind Watchmaker, "and in effect a sequel [to it]."[7]

Douglas H. Erwin, reviewing the book for Artificial Life, notes that life forms from fruit flies to man have far fewer genes than many biologists expected – in man's case, only some 20,000. "How could humans, in all our diversity of cell types and complexity of neurons, require essentially the same number of genes as a fly, or worse, a worm (the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans)?" asks Erwin. He answers his own question about the "astonishing morphological diversity" of animals coming from "such a limited number of genes", praising Carroll's "insightful and enthusiastic" style, writing in a "witty and engaging" way, pulling the reader into the complexities of Hox and PAX-6, as well as celebrating the Cambrian explosion of life forms and much else.[8]

References

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1859). "XIV". On The Origin of Species. p. 503. ISBN 0-8014-1319-2. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carroll, Sean B. "Endless Forms Most Beautiful". Sean B. Carroll. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Wolpert, Lewis (September 2005). "Clever Tinkering". American Scientist. 93 (5): 1.

- ↑ Coyne, J. A. (2005). "Switching on evolution". Nature. 435 (7045): 1029–1030. doi:10.1038/4351029a.

- ↑ "The New "Just So" Stories". BioScience. 55 (10): 898–899. 2005.

- ↑ Forbes, Peter (23 March 2016). "The Serengeti Rules by Sean B Carroll review – a visionary book about how life works". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ Pountain, Dick (November 2016). "Nature's 3D printer exposes Pokemon Go as a hollow replica". PC Pro (265): 26.

- ↑ Erwin, Douglas J. (2007). "Book Review: Endless Forms Most Beautiful". Artificial Life. 13 (1): 87–89.

External links

- Cornell University's Creative Machines Laboratory app to evolve three-dimensional shapes according to the principles laid out in the book