Affection

Affection, attraction, infatuation, or fondness is a "disposition or state of mind or body"[1] that is often associated with a feeling or type of love. It has given rise to a number of branches of philosophy and psychology concerning emotion, disease, influence, and state of being.[2] "Affection" is popularly used to denote a feeling or type of love, amounting to more than goodwill or friendship. Writers on ethics generally use the word to refer to distinct states of feeling, both lasting and spasmodic. Some contrast it with passion as being free from the distinctively sensual element.[3]

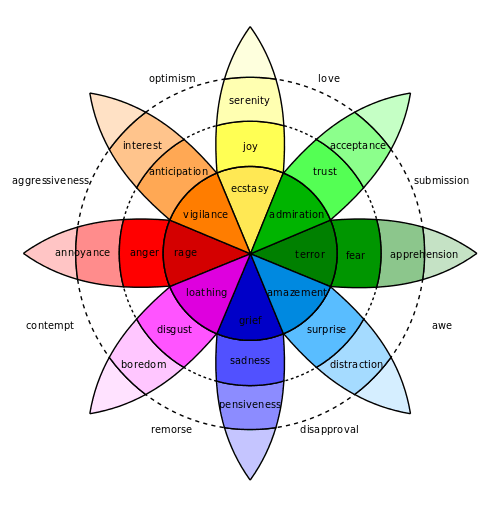

Even a very simple demonstration of affection can have a broad variety of emotional reactions, from embarrassment to disgust to pleasure and annoyance. It also has a different physical effect on both, the giver and the receiver.[4]

Restricted definition

More specifically, the word has been restricted to emotional states, the object of which is a living thing such as a human or animal. Affection is compared with passion, from the Greek "pathos". As such it appears in the writings of French philosopher René Descartes, Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza, and most of the writings of early British ethicists. However, on various grounds (e.g., that it does not involve anxiety or excitement and that it is comparatively inert and compatible with the entire absence of the sensuous element), it is generally and usefully distinguished from passion. In this narrower sense the word has played a great part in ethical systems, which have spoken of the social or parental affections as in some sense a part of moral obligation. For a consideration of these and similar problems, which depend ultimately on the degree in which the affections are regarded as voluntary, see H. Sidgwick, Methods of Ethics pp. 345–349.[3]

Expression

Affection can be communicated by words, gestures, or touches. Affectionate behavior may have evolved from parental nurturing behavior due to its associations with hormonal rewards.[5] Such affection has been shown to influence brain development in infants.[6] Expressions of affection can be unwelcome if they pose implied threats to one's well being. If welcomed, affectionate behavior may be associated with various health benefits. It has been proposed that positive sentiment increases the propensity of people to interact and that familiarity gained through affection increases positive sentiment among them.[7]

Affection can be displayed in different manners in different cultural societies. For example, in the Manchu ethnic group, mothers publicly kissing their infant is viewed as inappropriate, while publicly performing fellatio on their infant son is considered an appropriate act of affection.[8][9][10][11][12]

See also

References

- ↑ affection - Definitions from Dictionary.com

- ↑ 17th and 18th Century Theories of Emotions > Francis Hutcheson on the Emotions (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- 1 2

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Affection". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 299–300.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Affection". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 299–300. - ↑ "The Effects of Affection | Research Matters". researchmatters.asu.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- ↑ according to Communication professor Kory Floyd of the University of Arizona

- ↑ Infant Observation: International Journal of Infant Observation and Its Applications

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ↑ Clarke, John R. (2001). Looking at Lovemaking (1st paperback print ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-520-22904-4.

In the Manchu tribe, a mother will routinely suck her small son's penis in public but would never kiss his cheeks. Among adults, the Manchu believe, fellatio is a sexual act, but kissing—even between mother and infant son—is always a sexual act, and thus fellation becomes the proper display of motherly affection.

- ↑ Barre, Weston La (1975). "The Cultural Basis of Emotions and Gestures". In Davis, Martha. Anthropological Perspectives of Movement. Arno Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-405-06201-8.

Manchu kissing is purely a private sexual act, and though husband and wife or lovers might kiss each other, they would do it stealthily since it is shameful to do ... yet Manchu mothers have the pattern of putting the penis of the baby boy into their mouths, a practice which probably shocks Westerners even more than kissing in public shocks the Manchu.

- ↑ Barre, Weston La (1974). "The Cultural Basis of Emotions and Gestures". In Starr, Jerold M. Social structure and social personality. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 79.

- ↑ Halperin, David M.; Winkler, John J.; Zeitlin, Froma I. (1990). Before Sexuality. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-691-00221-7.

- ↑ Walls, Neal (2001). Desire, Discord and Death. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-89757-056-5.

Further reading

- Janice Raymond. 2001. A Passion for Friends. Publisher. Spinifex Press, ISBN 187675608X, 9781876756086

- Elizabeth Sibthorpe Pinchard.2012. Family Affection: A Tale for Youth. Publisher- Hardpress Publishing, 2012 ISBN 1290006709, 9781290006705

- Joshua Hordern. 2013. Political Affections: Civic Participation and Moral Theology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199646813

- Robin Becker. 2006. Domain of Perfect Affection. Publisher University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0822959313, 9780822959311

- Kory Floyd. 2006. Communicating Affection: Interpersonal Behavior and Social Context. Advances in Personal Relationships. Publisher Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521832055, 9780521832052

- Tuan Yi-fu. 1984. Dominance & affection: The making of pets. Publisher-Yale University Press (New Haven). ISBN 0300032226

- International Journal of Infant Observation and Its Applications. 2011. ISSN 1369-8036

- Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences ; Vol 16 Issue 2. 2006.

- Infant Observation: International Journal of Infant Observation and Its Applications.Why love matters: How affection shapes a baby's brain.2006.

- Gustav Moritz. 1850. Duty and Affection. Publisher-Oxford University

- Sue Gerhardt. 2004. Why Love Matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby's Brain. Publisher-Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1583918175, 9781583918173

- Gretchen Reydams-Schils. 2005. The Roman Stoics: Self, Responsibility, and Affection. Publisher University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226308375, 9780226308371

- Ariel Knafo & Robert Plomin. 2006. Parental Discipline and Affection and Children’s Prosocial Behavior:Genetic and Environmental Links

- MAURICE A. FELDMAN, LAURIE CASE ET AL. 1989. PARENT EDUCATION PROJECT III: INCREASING AFFECTION AND RESPONSIVITY IN DEVELOPMENTALLY HANDICAPPED MOTHERS: COMPONENT ANALYSIS, GENERALIZATION, AND EFFECTS ON CHILD LANGUAGE

- Halliday, James L. 1953. Concept of a Psychosomatic Affection. Publisher- Ronald Press Company

- Kory Floyd & Mark T. Morman. Affection received from fathers as a predictor of men's affection with their own sons: Tests of the modeling and compensation hypotheses. 2009.

External links

Quotations related to Affection at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Affection at Wikiquote