Egyptomania

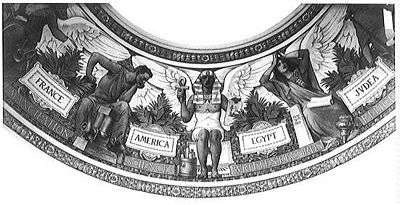

Egyptomania was the renewed interest of Europeans in ancient Egypt during the nineteenth century as a result of Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign (1798–1801) and, in particular, as a result of the extensive scientific study of ancient Egyptian remains and culture inspired by this campaign. In addition to its aesthetic impact on literature, art and architecture, it also played a role in the discussion about race, gender and national identity. Egyptomania is of particular importance to American culture because of the way in which the example of ancient Egypt served to create a sense of independent nationhood during the nineteenth century.[2] However, Egypt has had a significant impact on the cultural imagination of all Western Cultures.[3]

Culture

Since the early nineteenth century, the fascination with ancient Egypt seems to have affected every field of American culture. Some of the most important areas of culture influenced by Egyptomania are literature, architecture, art, film, politics and religion. There were two important waves of Egyptomania in the nineteenth century, especially in arts and design, which were both caused by publications about Egypt that became very popular:[4] Vivant Denon, Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypt (1802), and the Institute of Egypt's Description de l'Egypte (1809). Because of these publications, people became more and more interested in Egyptian culture and everything related to it. Ancient Egyptian images and representations were integrated into a wide variety of cultural sectors. They influenced the fine arts not just in the United States, but throughout the western world, e.g. Verdi's famous Aida.

Egyptian images and symbols also served for more trivial purposes, such as dessert services, furniture, decoration, commercial kitsch or even advertising.[4] There were parties and public events that had Egypt as a motto, where people wore special costumes. In general, people were fascinated by everything that had the label Egypt attached to it. And even today, this kind of fascination for Egypt and all things Egyptian still exists. Many different exhibitions about Egyptian culture in museums all over the world demonstrate people's continued interest in it.[5]

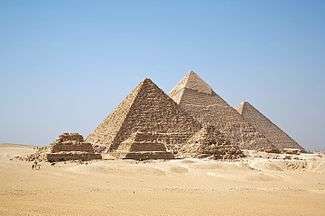

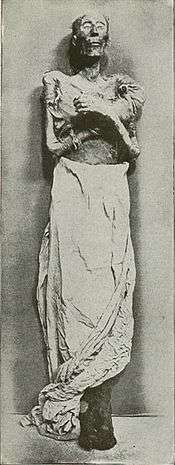

Fascinated by Egyptian culture, American literature, visual art and architecture absorbed what was becoming general knowledge about ancient Egyptian culture, making use of this knowledge in the contemporary debate about national identity, race, and slavery. Certain characteristic elements of Egyptian culture became particularly symbolically charged. The mummy, for example, represented the fascination of the Americans with the living dead, reanimation, revenge and anxiety about race.[6] This fascination went so far that 'mummy unwrapping parties' were organised, thus pushing the hysteria of the Americans with Egyptian myths further and further.[7] The figure of Cleopatra, hieroglyphic writing and deciphering, and the pyramid as maze and tomb are other examples of how ancient Egypt has been productive in the West, and specifically in the United States since the nineteenth century. Well-known literary works that make use of these symbolic references to Egypt include "Some Words With a Mummy" by E. A. Poe,[8] "Lost In A Pyramid Or The Mummy’s curse" by Louisa May Alcott[9] or The Marble Faun by Nathaniel Hawthorne. The impact of ancient Egyptian culture in architecture is called the Egyptian Revival, an important expression of neoclassicism in the United States. Well-known Egyptian images, forms and symbols were integrated in the contemporary style. This influence can best be seen in the architecture of cemeteries and prisons. Other examples of this influence are the Gold Pyramid House in Illinois or the famous Obelisk (Washington Monument) in Washington, D.C. Movies such as The Mummy (1999) (itself a remake of a 1932 Boris Karloff film) and its sequels demonstrate that ancient Egypt and the discovery of its secrets is still a powerful point of reference for contemporary western cultures. Important scholarly texts about this phenomenon in American culture include Scott Trafton’s Egypt Land (2004) and M. J. Schueller’s U.S. Orientalism (1998).

Science

In the early nineteenth century natural science based on Empiricism was still in its infancy. Though a lot of ground breaking discoveries were made, many ideas that were debated seriously by the intellectual community at that time may appear humorous at best, spurious and opportunistic at worst to observers from our time. This is true also with regard to Egyptology: the great interest in Egypt and its history spawned enormous efforts that produced indispensable knowledge as for instance the deciphering of hieroglyphics by Jean-François Champollion in 1824. Yet much of the work in and on Egypt was not performed by full-time scholars but by rich enthusiasts whose training and expertise did not quite match their interest. Major amounts of knowledge have been destroyed by poorly documented excavations and poorly performed dissections. The popularity of Egyptology in educated circles led to strange phenomena, as for instance when amateur Egyptologists would organize "Mummy Parties", social gatherings with a pseudo scientific outlook, which consisted mainly of "unwrapping" a mummy purchased for the purpose by the host.

Another rather strange chapter of nineteenth century science that is relevant with regard to Egyptomania is Craniology, the study of the human cranium that claimed to be able to determine an individual's intelligence and even character. Egyptian mummies served as an abundant source for the object of study — skulls. Craniology was especially important with regard of the question, whether Egyptians were black or white, a debate lead in light of the justification of slavery. The key figure for this period seems to be Samuel George Morton who founded the American School of Ethnology. He put forward the theory of Polygenesis claiming that there is not one but several human races who are in a hierarchical order with whites at the top and blacks at the bottom end of the scale. Although science today disapproves of Morton's findings it still revalidated his professional status, because Morton's American School was to a large degree responsible for the development of the current professional status of the sciences and the renunciation of puritan ideas of monogenesis and the Christian, clerical worldview, common at the time.[10]

Race and national identity

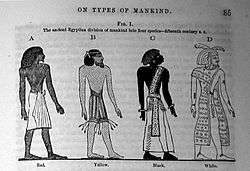

Egypt occupies a special location in-between historical and geographic regions: According to Richard White, Egypt is not easily placed within Africa or Asia, or within the East or the West. Therefore, it seems as if Egypt is "everybody’s past".[11] The figure of Egypt has been an important point of reference in the development of national identity in the western World, though these processes of identity formation are complex and involve many factors. Racial identity is central to these processes, particularly in the United States, where the emerging sense of a distinct national identity and the increasing conflict over slavery were inseparably linked in the first half of the 19th century. Paschal Beverly Randolph crystallized the way in which Egypt served as a model for the new nation when he said, "For America, read Africa; for the United States, Egypt" (1863). Among the large variety of ethnic groups that formed the population of the United States the common denominator was being non-black, being able to define oneself utilizing a binaristic Other. Historically, the attempt to scientifically establish a racial hierarchy as undertaken by the American School of Ethnology evoked an understanding of whiteness as the natural American national identity.[12] The racial identity of Egyptian pharaohs was used especially by 19th century scientists such as Samuel George Morton and his contemporaries to confirm the contemporary American racial hierarchy. This hierarchy served proponents of slavery to justify the inhuman treatment of slaves and the denial of civil rights for any but white Americans.[10] Types of Mankind (1854), the culmination of American School racial thinking, contains a major chapter on the racial characteristics of the ancient Egyptians, starting a controversy that still rages today.[13] Historians have put forward three main hypotheses which clearly contradict each other.[11] Scientists, historians and anatomists argue whether the Egyptians were white, black or hybrid (mixture of both). The argument draws on aspects such as wall paintings or the physique of mummies.

Going back to ancient Greek and Roman descriptions of Egyptians, Afrocentrist thinkers in the nineteenth century insisted that the Egyptians were black Africans, making it possible to provide an ancient and noble lineage that countered the degrading images proliferated by racist science and pro-slavery polemic. Prominent contributors to this debate include David Walker, James McCune Smith, Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois. Identifying with the enslaved Hebrews, African Americans had long used the biblical Exodus narrative to encode their right and desire for freedom, as the well-known spiritual "Go down, Moses" still testifies. David Walker's Appeal (1829) places this biblical story of liberation in tension with the assertion that the Pharaohs were black as well. The prominent black abolitionists James McCune Smith and Frederick Douglass countered white ethnography directly, as for example in Douglass' "Claims of the Negro Ethnologically Considered" (1854), drawing from findings of earlier European ethnologists such as James Prichard. At the turn of the 20th century, W. E. B. Du Bois shaped the concept of race and identity in yet another way by writing about the "double consciousness" of Africans in the "Diaspora", meaning the descendants of the slaves in the United States. This concept led to the twentieth century Black nationalist movements.

Notes and references

- ↑ cf. Trafton 2004, 2.

- ↑ cf. esp. Trafton 2004.

- ↑ For a chronological overview of the impact of Egypt on the Western imagination since ancient Greece see Egypt in the Western imagination.

- 1 2 cf. Whitehouse

- ↑ A prominent example, which also reflected upon the cultural meaning of this fascination, is the exhibition "Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art, 1730-1930" (Paris, Musée Du Louvre, 20 January – 18 April 1994; Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, 17 June – 18 September 1994; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, 16 October 1994 – 29 January 1995). The exhibition catalog was published by The National Gallery of Canada in 1994 (Humbert et al.).

- ↑ Trafton 2004:121-164

- ↑ cf. Trafton 2004:124-126

- ↑ cf. Trafton 2004:132-140

- ↑ cf. Trafton 2004:126-129

- 1 2 cf. Nelson 1998

- 1 2 Ater, 2003.

- ↑ cf. Nelson 1998.

- ↑ For example, Vincent Sarich and Frank Miele's Race: The Reality of Human Differences (2004), a recent attempt to add academic credibility to the popular — but scientifically discredited — notion that "race" constitutes an essential rather than a culturally constructed human difference, uses Egypt in a similar way.

References and further reading

- Ater, Renee. "Making History: Meta Warrick Fuller's 'Ethiopia". American Art 17.3 (2003): 12-31.

- Brier, Bob. Egyptomania. Brookville, NY: Hillwood Art Museum, 1992. ISBN 0-933699-26-3 (exhibition catalog)

- Curl, James Stevens. Egyptomania: The Egyptian Revival, A Recurring Theme in the History of Taste. Manchester University Press, 1994. Manchester, UK; New York: Manchester University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-7190-4126-0

- Draper, Theodore. The Rediscovery of Black Nationalism. New York: Viking Press, 1970. ISBN 0-670-59114-9

- Gillman, Susan. "Pauline Hopkins and the Occult: African-American Revisions of Nineteenth-Century Sciences" In: American Literary History, Vol 8, No.1, spring 1996, pp. 57–82

- Glaude, Eddie S. Exodus! Religion, Race, and Nation in Early Nineteenth-Century Black America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. ISBN 0-226-29819-1

- Gruesser, John Cullen. Black on Black: Twentieth-Century African American Writing About Africa. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2000. ISBN 0-8131-2163-9

- Humbert, Jean-Marcel, et al. Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art, 1730-1930. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1994. ISBN 0-88884-636-3 (Exhibition catalog: Paris, Musée Du Louvre, 20 January-18 April 1994; Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, 17 June-18 September 1994; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, 16 October 1994 – 29 January 1995)

- Howe, Stephen. Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. London ; New York: Verso, 1998. ISBN 1-85984-873-7

- Nelson, Dana D. National Manhood: Capitalist Citizenship and the Imagined Fraternity of White Men. Duke University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8223-2149-1

- Perniola, Mario, Enigmas. The Egyptian Moment in Society and Art, translated by Christopher Woodall, preface to the English Edition by the author, London-New York, Verso, 1995.

- Schueller, Malini Johar. U.S. Orientalisms: Race, Nation, and Gender in Literature, 1790-1890. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998. ISBN 0-472-10885-9

- Trafton, Scott Driskell. Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-Century American Egyptomania. New Americanists. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8223-3362-7

- Wallace, Maurice O. Constructing the Black Masculine: Identity and Ideality in African American Men's Literature and Culture, 1775-1995. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8223-2854-2

- Whitehouse, Helen. Review Article: "Egyptomanias"' In: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol 101, No.1, Jan 1997, pp. 158–161.

External links

- Egyptomania.org, a website devoted to covering all aspects of "Egyptomania" from both a scholarly and a popular perspective. Includes Bibliographies.

- American Egyptomania, a scholarly website maintained at George Mason University, under the guidance of Scott Trafton, the author of Egypt Land (2004). Focuses on expressions of Egyptomania in the United States starting in the early nineteenth century and includes excerpts from original documents.

- Underwood & Underwood Egypt Stereoviews, a digital library collection maintained by the American University in Cairo Rare Books and Special Collections Library. The collection highlights Egyptomania in the late nineteenth century.