Education in Haiti

| |

| Ministry of Education | |

|---|---|

| Minister of National Education & Professional Training | Nesmy Manigat |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | French, Haitian Creole |

| Literacy (2015) | |

| Total | 60.7% (est. 2015)[1] |

| Male | 64.3% |

| Female | 57.3% |

| Primary | 88%[2] |

| [1] | |

Formal Education rates in Haiti are among the lowest in the Western Hemisphere.[3] Haiti's literacy rate of about 61% (64.3% for males and 57.3% for females) is below the 90% average literacy rate for Latin American and Caribbean countries.[1] The country faces shortages in educational supplies and qualified teachers. The rural population is less educated than the urban.[3] The 2010 Haiti earthquake exacerbated the already constrained parameters on Haiti's educational system by destroying infrastructure and displacing 50-90% of the students, depending on locale.

International private schools (run by Canada, France, or the United States) and church-run schools educate 90% of students.[3] Haiti has 15,200 primary schools, of which 90% are non-public and managed by communities, religious organizations or NGOs.[4] The enrollment rate for primary school is 88%.[2] Secondary schools enroll 20% of eligible-age children. Higher education is provided by universities and other public and private institutions.

The educational sector is under the responsibility of the Ministre de l'Éducation Nationale et de la Formation Professionnelle (MENFP).[5] The Ministry provides very little funds to support public education. As a result, the private sector has become a substitute for governmental public investment in education as opposed to an addition.[6] The Ministry is limited in its ability to improve the quality of education in Haiti.[7]

Despite the deficiencies of the Haitian education sector, some Haitian leaders have attempted to make improving education a national goal. The country has attempted three major reform efforts, with a new one in progress as a response to the earthquake.[7][8]

History

Pre-independence

"African slaves were worked so hard by French plantation owners that half died within a few years; it was cheaper to import new slaves than to improve working conditions enough to increase survival. This attitude allowed no time or resources for the education of the enslaved.[9] Children of slaveholders were tutored in the early grades at home and then sent to France for further study. There were few schools in Sante Domingue. At the time of independence, years of war had demolished most infrastructure including any educational facilities.[9]

Independence through the 1800s

At the beginning of independence, King Christophe in the north of Haiti looked to Englishman William Wilberforce to build up the new nation's educational system.[9] King Christophe, though illiterate, understood the necessity of education. He was keen to show that formerly enslaved educated persons could hold their own with the educated of the world. Wilburforce encouraged Prince Saunders of Boston as well as four others to join their efforts at developing a Lancastrian model of education.[9] This is a Monitorial System where the teacher teaches the more advanced students who then in turn teach the less advanced. It is designed to educate a large number of students without benefit of a large number of professional teachers.

In the south of Haiti, President Alexandre Pétion turned to the French to guide his development of the educational system. He was personally familiar with it since he had studied ballistics in France.[9] His approach to the issue of inadequate numbers of teachers for the primary grades was to focus on secondary education in the Napoleonic approach to education.[10]

The first Constitution, promulgated in 1805 by King Christophe,[11] stated that "... education shall be free. Primary education shall be compulsory... State education shall be free at every level."[6] It guaranteed the right for everyone to teach –an "open-door policy" to private initiatives[12] which meant that every person would have the right to form private establishments for the education and instruction of youth.[8][13] The practice of providing accessible public education for all was established later when the Constitution was revised in 1807.[8] Much later in 1987, the declaration that education shall be a right for every citizen was added to the Constitution.[14]

(These educational goals expressed in the Constitution have not been achieved. In the beginning, the government's primary focus was on building schools to serve the children of the political elite.[6] These schools were predominantly found in urban areas, and patterned after the French and British school models.[6] At the end of the 19th century, there were 350 public schools in the country. It rose to approximately 730 by the eve of the American Occupation of Haiti in 1917.[6])

The American Occupation of 1915-1934

At the beginning of the United States occupation of Haiti there was an effort by the U.S. military to improve the education but not to the degree to which they had in the previous countries that they had occupied such as Cuba or the Puerto Rico.[15] Their initial assessment of the Haitian educational system was similar to many that had been made before.[16] The solution of the military, as first understood - of broadening the type of education and opening it up to more of the population, was considered a positive change by many Haitians as well as a number of American editorial writers who were keeping an eye on Haiti.[17] The most basic issue was that the current educational system did not successfully educate the average Haitian who spoke only Haitian Creole. The Haitian education system was built on the idea of the superiority of the French language over any other language, and the profound inferiority of Haitian culture to that of the French culture. This concept of superiority were born in the minds of the elite during the years of slavery and were re-enforced when the French Catholic Church was allowed to return and begin establishing schools as a result of the Concordat of 1860. The classical education, more commonly called an "academic" education was meant to prepare the elite for further education in France. There was heavy emphasis on the literature of France and rhetoric and very little science or practical education such as engineering and the learning tended to be rote. The language of instruction was French which was further re-enforced at home, among friends and in their reading materials down to food labels in their pantries. Non-elite students did not have the benefit of speaking French at home. In the schools that served the non-elite, French was still the language of instruction but there was a good chance the teacher was not fluent and the teaching became even more rote. Further down the social ladder, the quality of the teacher's either Creole or French was even less certain.[18] To ensure universal education for all, it was clear that profound, deep, systemic changes would need to begin.[19]

The Occupation's solution, however, was different than prior attempts at repair in that there was to be a new and extreme emphasis on agricultural education over the traditional academic education that the elites received.[19] The decision process surrounding this move to agricultural education and its implementation caused a great deal of concern and controversy in Haiti as well as in the U.S. - particularly among black American leaders. To them it smacked of attempts in the southern United States to limit black citizens to simple agricultural training to keep them from moving up the social economic ladder and to keep them from moving into a profession or positions of leadership.[20] (Note that there was an ongoing debate in the United States among leaders of black people at the time about the best educational path for black Americans – see the discussions between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois [ whose father had been born in Haiti.][21] - however no black leader advocated for solely agricultural training.) US. black leaders discovered that the U.S. decision makers in Haiti were all white military men - the majority of whom were southerners raised with Jim Crow laws. Concerns were raised about systemic racism such that one such leader Rayford W. Logan – an American French speaking advocate of Pan-Africanism - went on a fact finding mission, traveling much of the country and examining documents published by the Occupational forces. While there was no systematic record- keeping for all the Occupation years or for all the other efforts in the occupied countries, he was able to see clear patterns of denial of funds and minimization of Haitian culture. He concluded that the occupation's educational efforts were failing due to issues related to racism – some subtle and some blatant.[17]

In the initial treaty with Haiti no mention was explicitly made of educational improvements or policy as had been done in the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico.[22] Rayford considered this "an almost inexplicable omission".[23]

The Occupation budget for education in Haiti in 1920 paled in comparison to previous amounts allocated in other occupied countries. (Note that all monies for education came out of the Haitian treasury – there were no monies forthcoming from the United States.) [20][24]

- Haiti had $340,000.[25]

- Cuba had 20 times the budget ($7,000,000) for the same number of people.[25]

- Puerto Rico had 11 times the budget ($4,000,000) with half the people of Haiti.[25]

- Dominican Republic had 5 times the budget ($1,500,000) with a third of the people.[25]

While the U.S. was in the Dominican Republic, the salary of a teacher there had increased from $5 to $10 a month to $55 a month. Dominican rural schools had increased in number from 84 before the occupation to 489 in 1921. Logan attributed this disparity to racism, even though citizens of both countries were descended from African slaves.[17] The Dominican Republic citizens described themselves as white people or mulatto while Haitians described themselves as black or mulatto.[17]

In Haiti, the Occupation had essentially developed two school systems - one run by the U.S. – the agricultural sector called Service Techniques and the one run by the Haitian government – the academic from the elite lycee schools to the primary school in the mountain villages.

The implementation of the Service Techniques was highly problematic. The classes were taught by American teachers – few of whom spoke French let alone Haitian Creole. This required most classes to use translators which slowed down the teaching process considerably and added another cost.

Logan found that the salary differentials were such that Haitian primary school teachers were paid $72 a year while the American inspector of schools in that local area was paid between $1800 and $2400 a year. Academic schools were clearly deprived of funds while agricultural schools were generously funded. The Americans paid little attention to rural schools – home of the vast majority of Haitians.

After 13 years of Occupation there were only a third of the rural schools - 306 – as opposed to the 1074 required by the Haiti law of 1912.[26] There was also a dearth of government owned school buildings – Haiti had much more of a deficit in numbers of school buildings than other countries the U.S. had occupied. In the Philippines, the Occupation had built 1000 schools; in Cuba, 2600 schools with attendance jumping from 21,000 to 215,000.[27]

Given the concern about European influence in the Caribbean prior to World War I it is not surprising that Occupation forces wanted to diminish the influence of the Germans and French in Haitian life. Germans controlled important parts of the economy but it was the French who controlled the culture. It was much easier to replace the Germans with American businessmen but there was not an easy replacement for the French way of life. When the Haitian government asked that French Trappists (one of Catholicism's holy orders) be allowed to provide schooling, they were denied – even though this would have been a less expensive method of education. There was also a deep concern surrounding the separation of church and state among the Occupation leaders because it did not fit the model of American democracy. In the Americans' view the Catholic Church was intertwined with French influence and its reach into Haitian society needed to be reduced even though this would negatively affect academic education. At one point, two French professors were denied the ability to teach and the French Ambassador to the United States made an official complaint.[28] It was the hope of the Occupation to reduce cultural reliance on the French but the American military badly underestimated the intellectual, language and emotional ties to France among the elite.

There were some elite who at the beginning of the Occupation offered support for the Occupation's educational efforts but once it became it clear that there would not only be no support for the academic schools, that many of them would actually be closed – the elite became increasingly anti-American.[19]

While many in Haiti had a plethora of reasons to be frustrated with the Occupation it was actually students who instigated the final demonstrations against the Americans that finally forced them out. They had been promised scholarships to the Service Techniques but did not receive them. It was the straw that broke the camel's back and began the revolt that ended the Occupation in 1934.[17][19][29][30]

Post Occupation

The government attempted to expand access to public education in the 1940s.

Duvalier Era

This was halted during the Duvalier era. Between 1960 and 1971, 158 new public schools were built. Private education represented 20% of school enrollment in 1959-60.[6] After his son Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier took over in 1971, the public sector continued to stagnate, but the private sector accelerated partly due to a rule instituted by Baby Doc that religious missionaries were required to build an affiliated school with any new church.[31] By 1979-80 57% of enrollment in primary education, and 80% in secondary education was private.[6] During the Duvalier era a number of qualified teachers left the country to escape political repression.[6] During the 1980s, the average annual growth rates in private and public enrollment were 11% and 5%, respectively.[6]

Post Duvalier Era

The expansion of private schools increased further after the end of the Duvalier regime in 1986, as many religious communities established their own educational institutions. The years 1994-1999 were a peak period for school construction and the private sector has been growing exponentially since.[31]

Twenty-first century

Overview

Though the Constitution requires that a public education be offered free to all people,[32] the Haitian government has been unable to fulfill this obligation.[33] It spends about 10% of the federal budget on the country's elementary and secondary schools.[34] Out of the 67% enrollment rate for elementary school, 70% continue on to the third grade.[35] 21.5% of the population, age 5 and older, receive a secondary level education and 1.1% at the university level (1.4% for men compared to 0.7% for women).[36] Nearly 33% of children between the ages of 6 and 12 (500,000 children) do not attend school, and this percentage climbs to 40% for children ages 5 to 15 which accounts for approximately one million children.[36] The dropout rate is particularly high at 29% in the first basic cycle.[36] Close to 60% of children drop out of school before receiving their primary education certificate.[36] Of the two million children enrolled in the basic level, 56% are at the required age for the first cycle (ages 6 to 11).[36] While the mandated age for entering grade 1 is 6, the actual mean age is nearly 10, and students in grade 6 are on average almost 16, which is 5 years older than expected.[31] 83% of those ages 6–14 attended school in 2005. These rates are much lower for the poor.[31]

With the exception of higher education, private schools in Haiti account for 80% of total enrollments and serve the majority of Haitian students.[37] According to Wolff[37] there are three main types of schools that make up the private sector. The first and largest type of private schools are for-profit private schools run by entrepreneurs. These schools have very few, if any, books and unqualified teachers and school directors. They are popularly known as "écoles borlettes," which translates to "lottery schools," because "only by chance do the children learn anything."

The second type of private schools are those run by religious organizations such as Catholic and Evangelical churches, as well as some nonsectarian schools. The Ministry of Education at the time of the 2010 earthquake reported that Christian missionaries provide about 2,000 primary schools educating 600,000 students - about a third of the population that is school age.[38] Some of these schools offer a better quality of education than for-profit schools do, but they often have risky conditions and staff with no professional capabilities.

The final type of private school composes of "community schools," which are financed by whatever funds the local community can mobilize. They tend to be of very poor quality, worse than for-profit schools, but they do charge very low fees.

A handful of private schools in Haiti, mostly clustered around the capital city, Port-au-Prince, and accessible to the rich (except for limited scholarship fund opportunities), offer education with relatively high quality standards.[37]

Furthermore, three-fourths of all private schools operate with no certification or license from the Ministry of Education.[37] This literally means that anyone can open a school at any level of education, recruit students and hire teachers without having to meet any minimum standards.[37]

The majority of schools in Haiti do not have adequate facilities and are under-equipped. According to the 2003 school survey, 5% of schools were housed in a church or an open-air shaded area.[36] Some 58% do not have toilets and 23% have no running water.[36] 36% of schools have libraries.[36] The majority of workers, about 80% do not meet the existing criteria for the selection of training programs or are not accepted in these programs because of the lack of space in professional schools.[36] 6 out of every 1,000 workers in the labor market have a diploma or certificate in a technical or professional field.[36] In addition, 15% of teachers at the elementary level have basic teaching qualifications, including university degrees. Nearly 25% have not attended secondary school.[39] More than half of the teachers lack adequate teacher training or have had no training at all.[39] There is also a high attrition of teachers, as many teachers leave their profession for alternative better paying jobs. Sometimes they are not paid due to insufficient government funds.[40]

Current Issues

Structural violence

Anthropologist Paul Farmer states that an underlying problem, negatively affecting Haiti's education system, is structural violence.[41] He says that Haiti illustrates how prevailing societal factors, such as racism, pollution, poor housing, poverty, and varying forms of social disparity, structural violence limits the children of Haiti, particularly those living in rural areas or coming from lower social classes, from enrolling into school and receiving proper education.[42][43][44] Farmer has suggested that addressing unfavorable social phenomena, such as poverty and social inequality, the negative impacts of structural violence on education can be reduced and that improvements to the nation's educational standards and literacy rates can be attained.[42]

Educational Disincentives

Education in Haiti is valued. Literacy is a mark of some prestige. Students wear their school uniforms with pride.[45]:5 When Haitians are able to devote any income for schooling, it tends to take a higher proportion of their income. as opposed to most other countries.[45] There is a disconnect between the high opinion of education and educational attainment.[46]

Increasing a family's income would appear to solve the problem of insufficient family funds to pay for schooling.[45]:7In reality, though, there are a confluence of systems and actors in Haiti’s educational sphere that need to be taken into consideration.

Locale needs to be considered - depending on whether or not the community is urban or rural.[45]

There are the different actors - students, families, schools, teachers,curriculum, the government, and NGOs. These are briefly some of the issues that affect the various actors:

Students may delay their entry to school. They may be obliged to repeat grades. Sometimes they drop out.[45]

Teachers may be under-qualified.[45]:15 They may be underpaid.[45]:16

There may be insufficient schools in an area. They may lack adequate facilities. The expense of attendance may exceed a families resources.[45] There are some families that spend 40% of their income on school expenses says Education Minister Nesmy Manigat.[47]

Curriculum mismatches may occur. For example, the language of instruction is typically in French. The vast majority of students speak only Creole. French instruction is useful in producing students who will be able to attend a university in a French-speaking country such as France or Canada. There is limited educational opportunities for students who do not want to attend university, or who want to attend but cannot afford it.[45]

The Government provides few public schools. They are vastly outnumbered by private schools. The government is unable to enforce its desired policies with respect to education.[45] This inability has a myriad of ramifications. For example, the Haitian educational system has two exams that the government requires for a student to be promoted to the next grade. These exams are taken at the end of the 5th and 7th grades.[45]:5 :22However, many schools require exams at the end of every school year. The successful result will allow a promotion to the next grade- this includes public as well as private schools.[45]:11

The students are required to pay a fee to take the exams.[45]:29 If the fee is not paid, the student does not pass to the next grade regardless of how well they did during the school year. In rural areas, family income is greatest at the beginning of the school year when the harvest is in. It is easier to have children start school than finish. For families whose children do not get promoted, school fees must still be paid for the grade that is being repeated. This doubles the cost per grade or even more if the exam fees are once more not paid at the end of the year.[45]:5 This scenario is more likely for lower income families who can least afford the increased cost.

A solution to this issue of less family funds at the end of the school year that Lunde proposes is a change in the banking system.[45]:27 She suggests that access to loans at the end of the year based on anticipated harvest of the next year may help in these instances. The is an example of digging deep through a system’s issues and coming up with a possible solution that does not appear on the face of it to be connected to the problem.

Another solution to one of the key problems and the main bottleneck [45]:32 - teacher quality and quantity - is using the Diaspora. The World Bank estimates that 8 out of 10 college educated Haitians live outside the country.[45]:15 A way to attract them back to Haiti would be to offer dual citizenship.[45]:15

A number of schools are run by religious organizations but many more are run as a business to make a profit. "The consequence of the privatization of education is that private households are carrying the economic burden of both the real cost of education and the private actor’s profit" [45]:22 Haiti has the highest percentage of private schools than any other country.[45]:22

Repeating grades leads to a wider range of abilities in the classroom, making it that much more difficult teaching. This taxes an already unqualified teacher’s abilities. Often teachers are only a few grades ahead of the students they are teaching.[45]:16 Public school teachers typically are more qualified than private school teachers.[45]:15There are no laws or regulations with respect to setting up a school so anyone can do it and begin teaching.

There is a lack of schools in Haiti - insufficient schools given the number of potential students.[45]:17 One of the results of this is that it can be a long walk to school in the countryside, in the dark - a walk one way of 2 hours is not uncommon.[45]:17Parents can be reluctant to send a 6 year old that far on their own or even an older girl - there are safety concerns.[45]:19If the child does walk a long distance, they are often too tired to pay attention and may even fall asleep in class.[45]:18 The time getting to and from school also cuts into the time to help the family at home. If the parents are relying on the child’s labor, this long walk can be a disincentive to enrollment.[45]:19 Delaying school enrollment leads to students starting school overaged which in turn has its own issues.

Schools can be selective about who they admit. A number of them will only admit children who read and write already.[45]:12 This has made a big demand for pre-schools and creates one more hurdle to education for the lower income families.[45]:12 The best preschools cost more than the best private primary schools.[48] Education Minister Nesmy Manigat has set a new policy that disallows preschool graduations - a practice that has been to raise revenue rather than academic standards.[49]

Families use different strategies to provide education despite the disincentives.[45] Parents may focus their educational funds on the one child who appears to be the most promising academically. Or in the interests of fairness, allow one child to go to school, alternating children each year until all have had their chance and then repeat the cycle as funds allow. Since it may take at least 4 years to learn to read and write, dropping out before the first cycle is complete, typically makes an almost total loss of the money spent on that child's education.[45]:29

Given the lack of schools for the number of children who want education, there is a high demand for seats even if a family has the money to pay for school fees.[45]:31 At this point, it becomes a case of who they know - personal connections become necessary. Having connections to a Marraine or Parraine (Godmother or Godfather) who can influence a school's decision to enroll your child is vital.[45]:31 There may actually be a number of influencers in chain - that all must be paid a fee - in order to secure a seat.[45]:31

Impact of 2010 earthquake

_-_Rebuilding_schools_after_the_2010_earthquake%2C_Port_au_Prince%2C_Haiti.jpg)

The 2010 Haiti earthquake that struck on January 12, 2010 has exacerbated the already constraining factors on Haiti's educational system.[31] It is estimated that approximately 1.3 million children and youth under 18 were directly or indirectly affected. Nearly 4,200 schools were destroyed affecting nearly 50% of Haiti's total school and university population, and 90% of students in Port-au-Prince.[50] Of this population, 700,000 were primary school-age children between the ages of 6 and 12 years old. The earthquake caused death and injury to thousands of students and hundreds of professors and school administrators, however the actual number of casualties is unknown.[51] Most schools, including those that were minimally or not structurally affected at all, were closed for many months following the earthquake.[8] More than a year since the earthquake occurred, many schools still remain closed and, in many cases, tents and other semi-permanent structures have become temporary replacements for damaged or closed schools.[52] By early 2011, more than one million people, approximately 380,000 of whom are children, remained in crowded internally displaced people camps.[53]

The Haitian Ministry of Education estimates that the earthquake affected 4,992 (23%) of the nation's schools.[54] Higher education institutions were hit especially hard, with 87% gravely damaged or completely demolished.[51] In addition, the Ministry of Education building was completely destroyed.[55] The cost of destruction and damage to establishments and equipment at all levels of the education system is estimated at 478.9 million USD.[56] Another residual effect has been the number of children disabled by resulting injuries from the earthquake. These children are now experiencing permanent disabilities, and many schools lack the resources to properly attend to them.[57]

Successful models

While the Haitian state continues to rebuild the nation's infrastructure following the 2010 earthquake, private institutions are successfully educating Haitians by following a model of solidarity and subsidiarity. The Catholic Church remains the largest provider of education in Haiti, running 15% of schools nationally.[58] The majority of the 2,315 Catholic schools are attached to a parish or congregation.

Educational system

Formal education in Haiti begins at preschool, which is followed by 9 years of Fundamental Education (first, second and third cycles). Secondary education comprises 4 years of schooling. Starting at the second cycle of Fundamental Education, students have the option of following vocational training programs. Higher education follows completion of secondary education, and can be a wide range of years depending on program of study. The World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE) uses data from Haiti's 2002-2003 census administered by the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (MENFP),[59] the 2011 Presidential Commission on Education and Training (GTEF),[60] the Haitian Institute of Statistics and Information Technology[61] and the National Institute of Vocational Training (INFP)[62] to provide background information on the educational system in Haiti which is described below.[63]

Primary education

Although not compulsory, preschool is formally recognized for children between the ages of 3 and 5. Around 705,000 children below 6 years of age, representing 23% of the age group, have access to preschool education. The majority of preschools are located in elementary schools, and most of these are private and concentrated in the West department. Tuition costs have increased significantly over the last decade for preschools, going from 1628 gourdes (roughly $41) in 2004, to 4675 gourdes (roughly $117) in 2007, a 187% increase in just 3 years.

Elementary education is compulsory for children between 6 and 11. It consists of 3 cycles of 3 years each, which altogether is called "fundamental education". The 3rd cycle is completed either in elementary or in secondary school. Enrollment has seen a steady improvement in the last decade. According to IHSI, the Haitian Institute of Statistics and Information Technology, school enrollment has gone from 40.1% in 1990 to 86.7% in 2002, representing 2.1 million children. Although tuition in public schools is legally free for the first two cycles of fundamental education, equivalent to elementary education, 81.5% of these children go to private schools and pay fees, often due to the limited availability of public schools. One hundred forty five districts have no public school and 92% of the 15,268 elementary schools in Haiti are private. Tuition costs have increased significantly over the last decade. Average tuition for 2nd cycle classes in elementary school has almost tripled since 2000, sometimes going up to 92,500 gourdes ($2313).[63]

Secondary education

Less than 22% of children move on from elementary to secondary education. Of this 22%, 75% go to private schools who charge fees. Of the approximately 2,190 secondary schools in Haiti, 90.5% of secondary schools are private and 78% of them are located in urban areas. Roughly half of all schools are located in the West Department. There is a large discrepancy between the West and other regions in Haiti. Tuition costs have increased significantly over the last decade. Average tuition went from 5,000 gourdes ($125) in 2004 to 7,800 gourdes ($195) in 2007, representing an increase of 56% in 3 years.[63]

Higher education

Higher education in Haiti consists of 4 regional public universities including the State University of Haiti (Université d'État d'Haiti, UEH), 4 other public institutions each associated with their respective ministries, and the private sector. Public universities require an annual fee of 3,000 gourdes ($75). The State University of Haiti, located in Port-au-Prince, is the largest public university in Haiti and had 10,130 students enrolled in 2008, with 2,340 of them being first year students. Estimates on the number of students enrolled in higher education vary greatly from 100,000 to 180,000, leading to about 40% to 80% of students in the private sector. Many private universities and institutions have emerged in the last 30 years and in total there are around 200, 80% of which are in Port-au-Prince. 54 out of these 200 schools are officially approved by MENFP.[63]

A list of some universities in Haiti includes:

- Université Caraïbe (CUC)

- Université d'État d'Haïti (UEH)

- Université Notre Dame d'Haïti (UNDH)

- Université Adventiste d'Haïti (Haitian Adventist University)

- Centre de Techniques et d'Economie Appliquée (CTPEA)[51]

- Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Technologie (ENST)[51]

- Ecole Supérieure d'Infotronique d'Haïti (ESIH)[51]

- Institut Universitaire Quisqueya Amérique (INUQUA)[51]

- Université Quisqueya (uniQ)[51]

Vocational training

Vocational training in Haiti is given at different levels between the second half of secondary school ( 10 years of education) and the first half of university (13 years of education). Starting at the second cycle of fundamental education, students have the option of following vocational training instead of pursuing the formal education cycles. It is given through different formats and at different levels and it includes: technical education (EET) and professional education (EEP), housework skills (CM) and professional training (CFP). GTEF estimates the number of students to be in vocational training to be about 21,090.[63]

- Professional education (EEP): Professional education in Haiti is given to children having completed elementary education. Most programs last for 3 to 4 years, and are aimed at teaching the basic skills of a given vocation. According to INFP, there are about 40 of them, of which almost half are private.

- Technical education (EET): Around 50 out of the 138 institutions recognized by the INFP offer technical education at the secondary level, of which 4 are public. The programs usually last 3 years.

- Family centers ("Centres Menagers"): Family centers offer 2 to 3 year programs in clothing, cooking and/or housework arts, to people who have not completed elementary education. There is no age restriction and most participants are female adults of all ages. There are about 140 such institutions in Haiti. Many of them are located in elementary schools or in temporary locations, and operate in very bad conditions with almost no equipment.

- Professional training (Centre de Formation Professionnelle, CFP): Professional training is meant for candidates having completed 10 or 11 years of education, or for workers wishing to acquire skills that are specific to a certain vocation of their choice. According to the Ministry of Social Affairs (MAST), there are over 200 private institutions, which cover 24 occupations and operate under their supervision. MAST delivers Professional Certificates to those who complete professional training. The West department consists of 80% of these institutions. The two public centers that existed are now not functional. The Centre Educatif de Carrefour has been closed since 2000 and the Centre Educatif de Bel Air was destroyed in the 2010 earthquake.

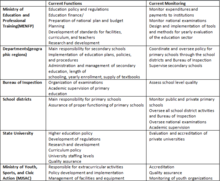

Governance

Education in Haiti is governed by the Haitian Ministry of National Education and Professional Training (Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Formation Professionnelle, or MENFP). Even though most of the schools in Haiti are private, the MENFP is charged with regulating the entire educational system.[8] The Ministry of Education has two main goals: (1) to provide educational services to its citizens and (2) to play a normative and regulatory role.[7] However, the MNEFP has been ineffective in fulfilling these goals because it is overstretched and lacks enough support. For example, there is now approximately one inspector per six thousand students who is responsible for providing accreditation, pedagogical supervision, and administrative support.[7]

The MENFP plays a significant role in the determination of curriculum content, regulations, validation of degrees and certificates, and inspections. Organizationally, the ministry does not adequately separate the functions of governance and policy making from the functions of management. There is no strong and independent policy making body.[7] In an effort to decentralize the education sector, a limited amount of responsibility and authority has been given to departments of Haiti (Haiti's ten geographic regions), school district offices, and inspection zones.[7]

Funding

The Haitian government, mainly the Ministry of Education is not in a position to close deficient schools because it is not equipped to take on the additional responsibility, nor does it have the resources or capacity to do so.[8] After a peak of 19% in 1987-88 and 22% in 1994-95, the percentage of Haiti's national budget allocated to education declined from 17% to 10% between 2001 and 2010[63] with 20% of education-related expenditures reaching rural areas, which is where 70% of Haiti's population is found.[8] This figure is low compared with other countries that are comparable according to the Human Development Index (HDI), which puts Haiti in 145th place out of 169 countries.[63] However, Haiti receives international aid which supplements, to a certain extent, the insufficient educational budget. In 2006 the country received $10.4 million to support basic education programs and $2.5 million to support higher education programs. According to USAID, ongoing US-supported education programs have lowered dropout rates and raised the performance of more than 75,000 Haitian youth.[64]

The substantial growth of the private sector, despite the constitutional guarantee of free education, indicates that the reality is that providing free education for all is very expensive. The majority of private schools do not receive any government subsidizes.[6] There is no government scholarship program to alleviate the burden on poor families. Help comes from the "Fonds de Parrainage", a private sector foundation which offers scholarships to needy children enrolled in eligible private schools.[6] The annual number of beneficiaries is around 13,000, representing a mere 1.3% of the student population enrolled in private schools.[6]

Financial support from the government is a salary subsidy covering approximately 500 teachers working full-time in private religious schools. This represents 2.5% of the private sector teaching force.[6] The public schools have collected fees because government funding has been insufficient. It had become common practice for school principals to require a parental financial contribution from each student.[6] Thus, for many parents, it did not make as much financial difference to put their children in public or private schools. When President Aristide returned from exile, he decided that public schools would no longer collect fees. This decision actually had a negative effect because it left public schools more destitute.[6] It is clear that the growth of the private sector has become a substitution for public investment, as opposed to an addition.[6]

Recent reform efforts

Despite the severe deficiencies of the Haitian education sector, many Haitian leaders have attempted to make improving education an important national goal. The country has attempted three major education reform efforts in recent years including the Bernard Reform of 1978, The National Plan on Education and Training (NPET) of 1997, and The Presidential Commission for Education in Haiti of 2008. More recently, following the 2010 earthquake, Haiti has partnered with the Inter-American Development Bank to propose a new 5-year educational plan.

Bernard Reform of 1978

The Bernard Reform of 1978 was an attempt to modernize and make the educational system more efficient. It was also an attempt at capacity building to satisfy the educational needs of the country despite its economic limitations.[7] The Bernard Reform sought to introduce vocational training programs designed as alternatives to traditional education in order to align the school structure with labor market demands.[7][8] The reform also restructured and expanded the secondary school system by separating it into academic and technical tracks.[7] In addition, Haitian Creole began to be utilized in classrooms as the language of instruction in the first 4 grades of primary school during this time period.[7] French and Creole are both official languages of Haiti. All Haitians speak Creole. The most privileged Haitians speak French.[7] The practice of using French rather than Creole in the classroom discriminates against the lower socioeconomic classes and the Bernard Reform was an attempt at addressing this issue.[7]

As part of the reform, a program was implemented in 1979 with the help of the World Bank to make Creole the first language of instruction rather than French. One thousand students were chosen to participate. During the first four years of school, all subjects were taught in Creole. In the third and fourth year, students were taught how to read and write in French. In the fifth year all teaching was done in French. The program was canceled in 1982 even though it was a great success. The elite had put pressure on the government to eliminate the program; they were concerned that the better educated citizens would be a threat to their power.[65]

In addition to failing to make Creole the initial language of instruction there were two other serious failures: lengthy delays in the implementation of new the curriculum and inadequate resources and infrastructure to support the proposed changes.[7] An issue that also became prevalent was that the majority of parents preferred to see their children attend universities because they saw the technical schools as low-prestige institutions. As a result, the labor market lacked sufficient jobs for new graduates of liberal arts programs, and consequently salaries lagged behind expectations.[7]

The National Plan on Education and Training of 1997

The National Plan on Education and Training was a plan that introduced a shift away from the French educational model.[7] The French educational model was one characterized by a highly centralized bureaucracy, which was teacher-centered and saw students as passive learners.[7] The NPET of 1997 marked a shift to a model of participatory learning based on student-centered approaches.[7] The NPET also shifted to a new paradigm of citizenship education aimed at developing civic knowledge and attitudes that would promote unity and an appreciation of the diversity in Haitian society, providing the foundation for an inclusive national identity.[7]

One of the principal goals of this plan was to uphold the Constitution and ensure that primary education would be made compulsory and free, neither of which have been realized to date.[8] The national education budget increased from 9% of the national budget in 1997 to 22% in 2000. This paid for programs to provide school lunches, uniforms, and bus transportation.[3] Additionally, in 2002 the government began a literacy campaign, facilitated by 30,000 literacy monitors and the distribution of 700,000 literacy manuals.[3] Overall, school attendance rose from 20% in 1994 to 64% in 2000.[3]

The NPET, however, was limited in its achievements. The goal of making primary education free and compulsory has not been met. Primary education remains beyond the reach of most Haitians, because they are highly privatized and very expensive.[7] In addition, there has been minimal decentralization of the educational sector because there are fears that the decentralization process will lead to fragmentation rather than resolve the problems of social polarization.[7] Furthermore, the NPET has not been successful in creating a space for communities to express their opinions through parent-teacher associations or other mechanisms.[7]

The Presidential Commission for Education in Haiti of 2008

The Presidential Commission for Education reported their recommendations to outgoing President René Préval and the Ministry of Education on recommendations for a new national curriculum.[8] The primary goals of the commission were to provide 100% enrollment of all school-age children, a free education to all, including textbooks and materials, and a hot meal daily for each child.[8] Lumarque stated that accelerated teacher training was essential for the attainment of these goals. In order to adequately reflect the needs of the people the commission traveled throughout the country asking parents and community leaders what they desired most for their children.[8] When the national curriculum plan is finalized, all public schools and those private schools that choose to participate will be expected to begin utilizing standardized teaching materials in addition to standardized test methods.[8][66]

The Operational Plan of 2010-2015

After Haiti's 2010 earthquake, the President of Haiti, René Préval in May 2010 gave the Inter-American Development Bank, IDB the mandate to work with the Education Ministry and the National Commission in preparing a major reform of the education system in a 5-year plan.[67] This 5 year, 4.2 billion USD plan calling for private schools to become publicly funded which would increase the access of education for all children.[8] The plan hopes to have all children enrolled in free education up to 6th grade by 2015, and 9th grade by 2020.[68] The IDB has committed 250 million USD of its own grant resources and has pledged to raise an additional 250million USD from third-party donors.[8]

The first phase of the plan is to subsidize existing private schools. According to the plan, the government would pay the salaries of teachers and administrators participating in the new system.[68] In order to participate in this new system, schools will undergo a certification process to verify the number of students and staff at their school, after which they will receive funding to upgrade facilities and purchase educational materials.[68] This would become the first step towards establishing a tracking mechanism in Haiti.[8] In order to remain certified, schools would have to comply with certain standards, including the adoption of a national curriculum, teacher training and facility improvement programs.[8] The plan will also finance the building of new schools and the use of school spaces to provide services such as nutrition and health care.[68]

Currently, most private schools serve approximately 100 students; yet they have the capacity for up to 400.[66] The intention of the plan is to eliminate waste and become more efficient in the schooling system. The goal is to eliminate low quality, inefficient schools and consolidate many others over time, and improve the overall quality of education in Haitian schools.[8][69]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "The World Factbook". Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Haiti boosts health and education in the past decade, says new UNDP report". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Haiti country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (May 2006). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Education: Overview". United States Agency for International Development. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ↑ "MENFP". Ministre de l'Éducation Nationale et de la Formation Professionnelle.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Salmi, Jamil. 2000. "Equity and Quality in Private Education: the Haitian paradox." A Journal of Comparative Education 30:163-178.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Luzincourt, K., & Gulbrandson, J. 2010. Education and Conflict in Haiti. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Carlson et al. Haitian Diaspora and Education Reform. 2011. Columbia University.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richard, Jean (2014). "Haiti: History of Mathematics Education". Mathematics and Its Teaching in the Southern Americas with An Introduction by Ubiratan D'Ambrosio. World Scientific Publishing Co. p. 241. ISBN 9789814590563.

- ↑ "The Revolution, Napoleon, and Education". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Al-Bataineh, Adel T and Mohamed A. Nur-Awaleh. 2005. International Education Systems And Contemporary Education Reforms. University Press of America. Lanham, Maryland.

- ↑ Haiti Government. 1801. Haiti Constitution of 1801. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ Haiti Government. 1987. Haiti Constitution 1987. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius (2008). Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press of America. p. 24. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ Logan, Rayford W. (Oct 1930). "Education in Haiti". The Journal of Negro History. Association for the Study of African American Life and History Inc. 15 (4): 442. JSTOR 2714206.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Logan, Rayford W. (Oct 1930). "Education in Haiti". The Journal of Negro History. Association for the Study of African American Life and History Inc. 15 (4): 401–460. doi:10.2307/2714206. JSTOR 2714206.

- ↑ Hebblethwaite, Benjamin (2012). "French and underdevelopment, Haitian Creole and development: Educational language policy problems and solutions in Haiti". Journal of Pidgen and Creole Languages. John Benjamins Publlishing Company. 27 (2): 255–302. doi:10.1075/jpcl.27.2.03heb.

- 1 2 3 4 Pamphile, Léon Dénius (2008). Clash of cultures :America's educational strategies in occupied Haiti, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Press of America. p. 177.

- 1 2 Logan, Rayford W. (Oct 1930). "Education in Haiti". The Journal of Negro History. Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc. 15 (4): 447. JSTOR 2714206.

- ↑ "Du Bois, Mary Silvina Burghardt". DuBoisopedia. University of Massachusetts Amherst Special Collections and Arhives. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius. Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press of America. p. 24. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius (2008). Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press of America. p. 26. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius (2008). Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. University Press of America. p. 54. ISBN 0761839925.

- 1 2 3 4 Pamphile, Leon Denius. Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press of America. p. 54. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius (2008). Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press of America. p. 458. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius (2008). vClash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press of America. p. xii. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius (2008). Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press of America. p. 43. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ Pamphile, Leon Denius (2008). Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied, 1915-1934. Lanham: University Free Press America. p. 84. ISBN 0761839925.

- ↑ "Dr. Leon Pamphile: "Haitians' & African Americans' Struggle Against Racism Through the NAACP". Chalres Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice. Harvard Law School. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Demombynes , Gabriel, Peter Holland, Gianmarco León. 2010. Students and the Market for Schools in Haiti. The World Bank. Latin America and the Caribbean Region. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ↑ Henriette Lunde. Youth and Education in Haiti – disincentives, vulnerabilities and constraints. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ Franz, Paul. "Haiti's Lost Children". Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ Ell Darren. "The Struggle for Education in Haiti", Rabble. CA, 10 August 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ↑ "UNICEF Humanitarian Action Report 2008", UNICEF.org. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper. 2008-2010. Ministry of Planning and External Cooperation. The Republic of Haiti. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wolff, L. 2008. Education in Haiti: The Way Forward. Washington, DC: PREAL. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ↑ "Missionaries Go to Haiti, Followed by Scrutiny". New York Times. New York Times. 2 February 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- 1 2 [World Bank 2007 Project Appraisal Document for Education for All Program]

- ↑ "Concern Training Teachers in Haiti", Education Partnership for children of conflict. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ↑ Farmer, Paul; foreword by Amartya (2004). Pathologies of power : health, human rights, and the new war on the poor : with a new preface by the author (2° édition. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24326-2.

- 1 2 Farmer, Paul E.; Bruce Nizeye; Sara Stulac; Salmaan Keshavjee (October 2006). "Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine". PLoS Medicine. 3 (10): 1686–1690. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449. PMC 1621099

. PMID 17076568.

. PMID 17076568. - ↑ The World Bank. "Haiti Overview". The World Bank. Retrieved 20 Mar 2013.

- ↑ Farmer, Paul (June 2004). "An Anthropology of Structural Violence". Current Anthropology. 45 (3): 305–325. doi:10.1086/382250.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Lunde, Henriette (2008). Youth and Education in Haiti: Disincentives, Vulnerabilities and Constraints (ebook ed.). Oslo, Norway: Fafo Institute of Applied International Studies (Oslo). p. 38.

- ↑ Luzincourt, Ketty; Gulbrandson, Jennifer (2010). Education And Conflict In Haiti: Rebuilding The Education Sector After The 2010 Earthquake. Special Report 245. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace. p. 3.

- ↑ "Right to Quality Education". Our World, Our Dignity, Our Future, 2015 European Year for Development. European Commission. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ Salmi, Jamil (2000). "Equity and Quality in Private Education: The Haitian paradox". Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 30 (2): 171. doi:10.1080/03057920050034101.

- ↑ Charles, Jacqueline (September 4, 2015). "From uniforms to apps, transforming Haiti education, one reform at a time". Miami Herald.

- ↑ Carlson et al. Haitian Diaspora and Education Reform. 2011. Columbia University.Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 INURED. 2010. The Challenge for Haitian Higher Education: A Post-Earthquake Assessment of Higher Education Institutions in the Port-au-Prince Metropolitan Area. Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED). Port-au-Prince: INURED. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ INEE. 2004. Minimum Standards. INEE: Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ UNICEF. 2011. Children in Haiti: One Year After - The Long Road from Relief to Recovery. UNICEF, Haiti Country Office. United Nations Children's Fund.

- ↑ Haiti Special Envoy to the United Nations.2008. Education | Haiti. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ UNESCO. 2010. UNESCO's Education Priorities in Haiti. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ Haiti Government. 2010. Haiti Earthquake PDNA: Assessment of Damage, Losses, General and Sectoral Needs. Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2010. Realising the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ Catholic Relief Services. June 2012. "Final Report of the National Survey of Catholic Schools in Haiti." Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ↑ Ministere de l'Education Nationale et de la Formation Professionnelle

- ↑ Groupe de Travail sur l'Education et la Formation

- ↑ IHIS - Institut Haitien de Statistiques et d'Informatiques

- ↑ Institut National de la Formation Professionnelle

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Suzata, Eriko. 2011. Education in Haiti: An Overview of Trends, Issues, and Plans. World Innovative Summit for Education. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ Seelke, Clare Ribando. 2007. Overview of Education Issues and Programs in Latin America. Congressional Research Report for Congress. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ World Education Encyclopedia: A Survey of Educational Systems Worldwide. Detroit, MI: Gale Group. 2002. ISBN 978-0028655949.

- 1 2 McNulty, B. 2011. The Education of Poverty: Rebuilding Haiti's School System After Its "Total Collapse". The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs , 35 (1), 111.

- ↑ mandate

- 1 2 3 4 Bruemmer, R. (March 5, 2011). "Schools Key to Recovery". Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Canada. pp. 1A.

- ↑ Inter-American Development Bank. 2010. Haiti Gives IDB Mandate to Promote Major Educational Reform. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

Further reading

- Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina, Annie Georges, and Susan Pozo. "Migration, Remittances, and Children's Schooling in Haiti." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 630 (2010): 224-44. Print.

- Angulo, A. J. "Education during the American Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934." Historical Studies in Education 22.2 (2010): 1-17. Print.

- Bataineh, Adel T., and Mohamed A. Awaleh. International Education Systems and Contemporary Reforms. ISBN 9780761830467 Lanham, MD: U of America, 2005. 123-138. Print.

- Atasay, Engin, and Garrett Delavan. "Monumentalizing Disaster and Wreak-Construction: A Case Study of Haiti to Rethink the Privatization of Public Education." Journal of Education Policy 27.4 (2012): 529-53. Print.

- Cabrera, Angel, Frank Neville, and Samantha Novick. "Harnessing Human Potential in Haiti." Innovations 5.4 (2010): 143-9. Print.

- Campbell, Carl. "Education and Society in Haiti 1804-1843." Caribbean Quarterly 2004: 14. JSTOR Journals. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

- Clément J. History of Education in Haiti: 1804-1915 (First Part). Revista de Historia de América [serial online]. 1979:141. Available from: JSTOR Journals, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 21, 2015

- Clement J. History of Education in Haiti: 1804-1915. Revista de Historia de América [serial online]. 1979:33. Available from: JSTOR Journals, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 21, 2015.

- Colon, Jorge. "A Call For A Response From The International Chemistry Community. (Science For Haiti(." Chemistry International 4 (2012): 10. Academic OneFile. Web. 29 Apr. 2015.

- Gagneron, Marie. "The Development of Education in Haiti." Order No. EP17380 Atlanta University, 1941. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

- Dale, George A. Education in the Republic of Haiti. Washington: U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education, 1959. Print.

- Doucet, Fabienne. "Arrested Development: How Lack of Will Cripples Educational Reform in Haiti." Journal of Haitian Studies 18.1, Special Issue on Education & Humanitarian Aid (2012): 120-50. Print.

- Fevrier, Marie M. "The Challenges of Inclusive Education in Haiti: Exploring the Perspectives and Experiences of Teachers and School Leaders." Order No. 3579388 Union Institute and University, 2013. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

- Machlis, Gary E, Jorge Colón, and Jean E. McKendry. Science for Haiti: A Report on Advancing Haitian Science and Science Education Capacity. Washington, D.C: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011. Print.

- Joint, Louis A, and Martin M. Saint. Système Éducatif Et Inégalités Sociales En Haïti: Le Cas Des Écoles Catholiques Congrégationistes Saint Martial, Saint Louis De Bourbon Et Juvénat Du Sacré-Coeur. S.l.: s.n., 2005. Print.

- Joseph, Carole Berotte, and Arthur K. Spears. The Haitian Creole Language :History, Structure, use, and Education. Lanham Md.: Lexington Books, 2010. Print.

- Moy, Yvette. "An Editor's Journey: Return to Haiti." Diverse: Issues in Higher Education 29.5 (2012): 14-7. Print.

- Newswire, PR. "Landmark MIT-Haiti Initiative Will Transform Education in Haiti." PR Newswire US (2013)Print.

- Paproski, Peter John. "Community Learning in Haiti: A Case Study." M.A. McGill University (Canada), 1998. Print.Canada

- Rea, Patrick Michael, "The Historic Inability of the Haitian Education System to Create Human Development and its Consequences" (2014). Dissertations and Theses, 2014-Present. Paper 463.

- Salmi, J. "Equity And Quality In Private Education: The Haitian Paradox." Compare 30.2 (2000): 163-78. ERIC. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

- Sandiford, Gladwyn A. "Rebuilding Haiti's Educational Access: A Phenomenological Study of Technology use in Education Delivery." Ph.D. Walden University, 2013. Print.United States -- Minnesota: .

- Vallas, Paul, Tressa Pankovits, and Elizabeth White. Education in the Wake of Natural Disaster. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2014. Print.

- Verna, Chantalle F. "Haiti, the Rockefeller Foundation, and UNESCO’s Pilot Project in Fundamental Education, 1948-1953." Diplomatic History (2015)Print.

- Wang, Miao, and MCSunny Wong. "FDI, Education, and Economic Growth: Quality Matters." Atlantic Economic Journal 39.2 (2011): 103-15. Print.