Economics of coffee

r:Coffea canephora

m:Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica

a:Coffea arabica

Coffee is a popular beverage and an important commodity. Tens of millions of small producers in developing countries make their living growing coffee. Over 2.25 billion cups of coffee are consumed in the world every day.[1] Over 90% of coffee production takes place in developing countries - mostly South America, while consumption happens mainly in the industrialized economies.[1]

25 million small producers rely on coffee for a living worldwide,[2] in Brazil alone, where almost a third of all the world's coffee is produced, over 5 million people are employed in the cultivation and harvesting of over 3 billion coffee plants;[2] it is a more labour-intensive culture than alternative cultures of the same regions as sugar cane or cattle, as it is not subject to automation and requires constant attention.

Coffee is a major export commodity: it was the top agricultural export for twelve countries in 2004,[3] the world's seventh-largest legal agricultural export by value in 2005,[4] and "the second most valuable commodity exported by developing countries," from 1970 to circa 2000.[5][6][7] This last fact is frequently misstated; see coffee commodity market.

Further, green (unroasted) coffee is one of the most traded agricultural commodities in the world,[8] and is traded in futures contracts on many exchanges, including the New York Board of Trade, New York Mercantile Exchange, New York Intercontinental Exchange, and the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange. The world's largest transfer point for coffee is the port of Hamburg, Germany.

World production

| Top Ten Green Coffee Producers – 2011 (millions of metric tons) | |

|---|---|

| | 2.70 |

| | 1.28 |

| | 0.63 |

| | 0.47 |

| | 0.37 |

| | 0.33 |

| | 0.30 |

| | 0.28 |

| | 0.25 |

| | 0.24 |

| World Total | 8.46 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) | |

In 2009 Brazil was the world leader in production of green coffee, followed by Vietnam, Indonesia, Colombia and Ethiopia.[9] Arabica coffee beans are cultivated in Latin America, eastern Africa, Arabia, or Asia. Robusta coffee beans are grown in western and central Africa, throughout southeast Asia, and to some extent in Brazil.[10]

Beans from different countries or regions can usually be distinguished by differences in flavor, aroma, body, and acidity.[11] These taste characteristics are dependent not only on the coffee's growing region, but also on genetic subspecies (varietals) and processing.[12] Varietals are generally known by the region in which they are grown, such as Colombian, Java and Kona.

[13]Coffee in India

In 16th century a holy sufi saint Baba Budan reportedly smuggled “seven coffee seeds”from Arabia and planted in the courtyard of his hermitage in Chikmagalure of Karnataka. From there coffee spread over to other parts and presently 16 varieties of coffee is grown in India. Coffee was first introduced in Andhra Pradesh in 1898 by Mr. Brodi, a Brtisher in Pamuleru valley in East Godavari district. Subsequently it spread over to Pullangi (East Godavari district) and Gudem (Visakhapatnam district) agency tracks. In 1920s even though it spread over to Ananthagiri in Araku valley and Chintapalli areas, coffee cultivation remained dormant for a long time. In 1960s, the Andhra Pradesh Forest Department developed coffee plantations in 10100 acres in Reserve forest areas. These plantations were handed over to the A.P. Forest Development Corporation in the year 1985. In the year 1956 after the formation of Girijan Cooperative Corporation (GCC), the Coffee Board identified GCC for promoting coffee plantations. Since then GCC started making efforts to develop coffee plantation through local tribal famers. A separate coffee wing was carved out in GCC and promoting coffee in around 4000 hectares taken up. Thus, the coffee grown in Araku valley by the tribal farmers under organic practices attained recognition as “Araku coffee”. After 1985, GCC promoted another organization by name “Girijan Coop. Plantation Development Corporation” (GCPDC) exclusively to develop coffee plantations in tribal areas. All the plantations developed by GCC and GCPDC were handed over to the tribal farmers @ 2 acres to each family. In July, 1997 the employees working in GCPDC were deployed to ITDA and coffee expansion was taken up under Five year Plan and MGNREGS. Thus presently the coffee cultivation reached 1 lakh acres and maintained by the tribal farmers. In India, while coffee plantations were well developed over the last century in Western ghats, expansion of coffee in Eastern ghats is still to develop. Coffee is grown under organic practices under shades of Mango, Jackfruit, Banana and silver oak trees. It also helps in environmental conservation and ecological balances. Around 1 lakh tribal families living in this region are getting financially stabilized through coffee cultivation. The more welcoming development is that the tribal famers have given up their traditional “Podu” cultivation and now switched over to coffee cultivation on a large scale. It is not an exaggeration to say that in Araku region, the coffee cultivation is not only helping conservation of forest and ecological balances but also as a viable high economic pursuit to the tribal farmers. The coffee cultivated in this region at an altitude of 900 to 1100 m MSL is having unique qualities due to medium acidity in soil. During the year 2015-16 GCC collected 1400 M.Ts of coffee, marketed the same through E-auctions

Consumption

In the year 2000 in the US, coffee consumption was 22.1 gallons (100.468 litres) per capita.[14] More than 150 million Americans (18 and older) drink coffee on a daily basis, with 65 percent of coffee drinkers consuming their hot beverage in the morning. In 2008, it was the number-one hot beverage of choice among convenience store customers, generating about 78 percent of sales within the hot dispensed beverages category.[15]

Pricing

According to the Composite Index of the London-based coffee export country group International Coffee Organization the monthly coffee price averages in international trade had been well above 100 US cent/lb during the 1970s and 1980s, but then declined during the late 1990s reaching a minimum in September 2001 of just 41.17 US cent per lb and stayed low until 2004. The reasons for this decline included a collapse of the International Coffee Agreement of 1962–1989[16] with Cold War pressures, which had held the minimum coffee price at US$1.20 per pound.

The expansion of Brazilian coffee plantations and Vietnam's entry into the market in 1994 when the United States trade embargo against it was lifted added supply pressures to growers. The market awarded the more affordable Vietnamese coffee suppliers with trade and caused less efficient coffee bean farmers in many countries such as Brazil, Nicaragua, and Ethiopia not to be able to live off of their products, which at many times were priced below the cost of production, forcing many to quit the coffee bean production and move into slums in the cities. (Mai, 2006).

The decline in the ingredient cost of green coffee, while not the only cost component of the final cup being served, occurred at the same time as the rise in popularity specialty cafés, which sold their beverages at unprecedented high prices. According to the Specialty Coffee Association of America, in 2004 16% of adults in the United States drank specialty coffee daily; the number of retail specialty coffee locations, including cafés, kiosks, coffee carts and retail roasters, amounted to 17,400 and total sales were $8.96 billion in 2003.

Specialty coffee, however, is frequently not purchased on commodities exchanges—for example, Starbucks purchases nearly all its coffee through multi-year, private contracts that often pay double the commodity price.[17] It is also important to note that the coffee sold at retail is a different economic product than wholesale coffee traded as a commodity, which becomes an input to the various ultimate end products so that its market is ultimately affected by changes in consumption patterns and prices.

In 2005, however, the coffee prices rose (with the above-mentioned ICO Composite Index monthly averages between 78.79 (September) and 101.44 (March) US Cent per lb). This rise was likely caused by an increase in consumption in Russia and China as well as a harvest which was about 10% to 20% lower than that in the record years before. Many coffee bean farmers can now live off their products, but not all of the extra-surplus trickles down to them, because rising petroleum prices make the transportation, roasting and packaging of the coffee beans more expensive.

Prices have risen from 2005 to 2009 and sharply in the second half of 2010 on fears of a bad harvest in key coffee-producing countries, with the ICO indicator price reaching 231 in March 2011[18]

Classification

A number of classifications are used to label coffee produced under certain environmental or labor standards. For instance, "Bird-Friendly" or "shade-grown coffee" is said to be produced in regions where natural shade (canopy trees) is used to shelter coffee plants during parts of the growing season. Organic coffee is produced under strict certification guidelines, and is grown without the use of artificial pesticides or fertilizers..

Fair trade coffee is produced by small coffee producers who belong to cooperatives; guaranteeing for these cooperatives a minimum price, though with historically low prices, current fair-trade minimums are lower than the market price of only a few years ago. Fairtrade America is the primary organization currently overseeing Fair Trade coffee practices in the United States, while the Fairtrade Foundation does so in the United Kingdom.

Commodity chain for the coffee industry

v2.png)

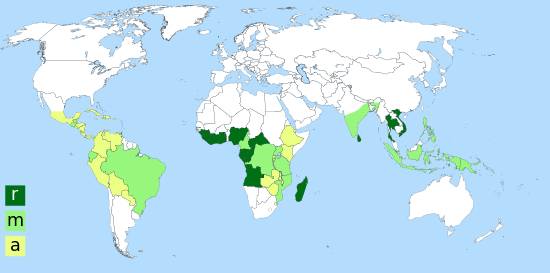

World Map based on Coffee imported by country in 2005. Map shows gross imports, not how much coffee stays within the country or how much is consumed. Some countries re-export significant portions of their coffee imported. |

The coffee industry currently has a commodity chain that involves producers, middlemen exporters, importers, roasters, and retailers before reaching the consumer.[19] Middlemen exporters, often referred to as coffee "coyotes," purchase coffee directly from small farmers.[19] Large coffee estates and plantations often export their own harvests or have direct arrangements with a transnational coffee processing or distributing company. Under either arrangement, large producers can sell at prices set by the New York Coffee Exchange.

Green coffee is then purchased by importers from exporters or large plantation owners.[19] Importers hold inventory of large container loads, which they sell gradually through numerous small orders. They have capital resources to obtain quality coffee from around the world, capital normal roasters do not have. Roasters' heavy reliance on importers gives the importers great influence over the types of coffee that are sold to consumers.

In the United States, there are around 1,200 roasters. Roasters have the highest profit margin in the commodity chain.[19] Large roasters normally sell pre-packaged coffee to large retailers, such as Maxwell House, Folgers and Millstone.

Coffee reaches the consumers through cafes and specialty stores selling coffee, of which, approximately, 30% are chains, and through supermarkets and traditional retail chains. Supermarkets and traditional retail chains hold about 60% of market share and are the primary channel for both specialty coffee and non-specialty coffee. Twelve billion pounds of coffee is consumed around the globe annually, and the United States alone has over 130 million coffee drinkers.

Coffee is also bought and sold by investors and price speculators as a tradable commodity. Coffee futures contracts are traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) under ticker symbol KC with contract deliveries occurring every year in March, May, July, September, and December.[20]

Fair trade coffee

According to the World Fair Trade Organization and the other three major Fair Trade organizations (Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, Network of European Worldshops and European Fair Trade Association), the definition of fair trade is "a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade". The stated goal is to offer better trading conditions to marginalized producers and workers. Fair trade organizations, along with the backing of consumers, campaign for change in the rules and practice of conventional international trade. However, not all coffee producers are happy with the methods or results.

Fair Trade organizations promote a trade environment in which the coffee importer has a direct relationship with the coffee producer, excluding the middlemen. Coffee importers provide credit to certified farmers to help them stay out of debt with coffee traders so they can develop long-lasting trade relationships. Producer organizations are paid a floor price (Fairtrade Minimum Price) of US$125 cents per pound for Fairtrade certified washed Arabica and US$120 cents for unwashed Arabica, or the market price, if higher.[21] The free trade price of coffee rose above this minimum in September 2007, but due to recent economic events, the free trade price dropped back below this minimum in October 2008.[22] The fair trade price for (conventional natural robusta) coffee has been $1.01 since June 2008 [23] The price of conventional commodity coffee was also over $1 in 2008, but about $0.70 in 2009.

Fairtrade certification is not free; there is an application fee, initial certification fee, membership dues, annual audit fees and more. Certification can cost thousands of Euros for a single plantation.[24] Large corporate farms can often handle the paperwork and recuperate the cost of certification more easily than small, independent farms. As a result, there are plenty of small, independent farms that are not Fairtrade certified even though they meet or exceed the Fairtrade standards.

Coffee and the environment

Originally, coffee farming was done in the shade of trees, which provided natural habitat for many animals and insects, roughly approximating the biodiversity of a natural forest.[25][26] These traditional farmers used compost of coffee pulp and excluded chemicals and fertilizers. They also typically cultivated bananas and fruit trees as shade for the coffee trees,[27] which provided additional income and food security.

However, in the 1970s and 1980s, during the Green Revolution, the US Agency for International Development and other groups gave eighty million dollars to plantations in Latin America for advancements to go along with the general shift to technified agriculture.[28] These plantations replaced their shade grown techniques with sun cultivation techniques to increase yields, which in turn destroyed forests and biodiversity.[29]

Sun cultivation involves cutting down trees, and high inputs of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Environmental problems, such as deforestation, pesticide pollution, habitat destruction, soil and water degradation, are the effects of most modern coffee farms, and the biodiversity on the coffee farm and in the surrounding areas suffer.[25] Of the 50 countries with the highest deforestation rates from 1990 to 1995, 37 were coffee producers[30]

As a result, there has been a return to both traditional and new methods of growing shade-tolerant varieties. Shade-grown coffee can often earn a premium as a more environmentally sustainable alternative to mainstream sun-grown coffee.

See also

References

- 1 2 Ponte, Stefano (2002). "The 'Latte Revolution'? Regulation, Markets and Consumption in the Global Coffee Chain". World Development. Elsevier Science Ltd. 30: 1099–1122. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00032-3. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- 1 2 FAO, 2007

- ↑ "FAO Statistical Yearbook 2004 Vol. 1/1 Table C.10: Most important imports and exports of agricultural products (in value terms) (2004)" (PDF). FAO Statistics Division. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ "FAOSTAT Core Trade Data (commodities/years)". FAO Statistics Division. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2007. To retrieve export values: Select the "commodities/years" tab. Under "subject", select "Export value of primary commodity." Under "country," select "World." Under "commodity," hold down the shift key while selecting all commodities under the "single commodity" category. Select the desired year and click "show data." A list of all commodities and their export values will be displayed.

- ↑ Talbot, John M. (2004). Grounds for Agreement: The Political Economy of the Coffee Commodity Chain. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 50.

So many people who have written about coffee have gotten it wrong. Coffee is not the second most valuable primary commodity in world trade, as is often stated. [...] It is not the second most traded commodity, a nebulous formulation that occurs repeatedly in the media. Coffee is the second most valuable commodity exported by developing countries.

- ↑ Pendergrast, Mark (April 2009). "Coffee: Second to Oil?". Tea & Coffee Trade Journal: 38–41. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ Pendergrast, Mark (1999). Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03631-8.

- ↑ Mussatto, Solange I.; Machado, Ercília M. S.; Martins, Silvia; Teixeira, José A. (2011). "Production, Composition, and Application of Coffee and Its Industrial Residues". Food and Bioprocess Technology. 4 (5): 661–72. doi:10.1007/s11947-011-0565-z.

- ↑ "Coffee: World Markets and Trade" (PDF). Foreign Agricultural Service Office of Global Analysis. United States Department of Agriculture. December 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ "Botanical Aspects". London: International Coffee Organization. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Davids, Kenneth (2001). Coffee: A Guide to Buying Brewing and Enjoying (5th ed.). New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-24665-X.

- ↑ Castle, Timothy James (1991). The Perfect Cup: A Coffee Lover's Guide to Buying, Brewing, and Tasting. Reading, Mass.: Aris Books. p. 158. ISBN 0-201-57048-3.

- ↑ "Middlemen still a menace for Araku coffee growers: GCC chief". http://www.newindianexpress.com/. 24 October 2016. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Bottled water pours past competition". DSN Retailing Today. 13 October 2003.

- ↑ Fact Sheets: Coffee Sales

- ↑ Daviron, Benoit; Ponte, Stefano (2005). "3". The Coffee Paradox. Zed Books, London & NY. p. 86. ISBN 1-84277-457-3

- ↑ Rickert, Eve (15 December 2005). "Environmental effects of the coffee crisis: a case study of land use and avian communities in Agua Buena, Costa Rica". M.Sc. Thesis, The Evergreen State College.

- ↑ ICO. "ICO Indicator Prices".

- 1 2 3 4 "www.globalexchange.org". Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- ↑ NYMEX Coffee Futures Contract Overview via Wikinvest

- ↑ "Minimum payment for coffee beans". Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ↑ "Price of a pound of coffee delivered in November 2008". Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ↑ "FLO Fairtrade Minimum Price and Premium Table" (PDF). Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ "FLO-CERT Fairtrade Certification company" (PDF). Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- 1 2 Janzen, Daniel H. (Editor) (1983). Natural History of Costa Rica. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-39334-8.

- ↑ "Fact Sheets". si.edu. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ Krigsvold, Marsha (Editor) (2001). Diversification Options for Coffee Growing Areas in Central America. Chemonics International Inc.

- ↑ "NRDC: Coffee, Conservation, and Commerce in the Western Hemisphere - Chapter 3". nrdc.org. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ The grind over sun coffee, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center

- ↑ "11 Incredible Facts About The Global Coffee Industry". businessinsider. 2011.

External links

- Eco-certified coffee: How much is there? – Market share of eco-certified coffees as of 2013 with links to references and industry sources.

- Corporate coffee: How much is eco-certified? – Top North American coffee brands and the amount of certified coffees each purchased annually, most 2008-2013.

- Coffee latest trade data on ITC Trade Map

- Articles on world coffee trade at the Agritrade web site.