Economic history of the world

| Economics |

|---|

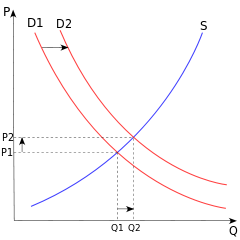

Supply and Demand graph, illustrating one of the most important economic principles |

|

|

| By application |

|

| Lists |

|

The economic history of the world is a record of the economic activities (i.e. the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services) of all humans, spanning both recorded history and evidenced prehistory.

Paleolithic

Throughout the Paleolithic Era the primary socio-economic unit was the band (small kin group).[1] Communication between bands occurred for the purposes of trading ideas and stories, tools, foods, skins and other commodities, and for the exchange of mates. Economic resources were constrained by typical ecosystem factors: density and replacement rates of edible flora and fauna, competition from other consumers (organisms) and climate.[2] Throughout the Upper Paleolithic, humans both dispersed and adapted to a greater variety of environments, and also developed their technologies and behaviors to increase productivity in existing environments[3][4] taking the global population to between 1 and 15 million.[5]

It has been estimated that throughout prehistory, the world average GDP per capita was about $158 per annum (adjusted to 2013 dollars), and did not rise much until the Industrial Revolution.[6]

This age was from 500,000- 10,000 BC.[7]

Mesolithic

This period began with the end of the last glacial period over 10,000 years ago involving the gradual domestication of plants and animals and the formation of settled communities at various times and places.

Neolithic

Within each tribe the activity of individuals was differentiated to specific activities, and the characteristic of some of these activities were limited by the resources naturally present and available from within each tribe's territory, creating specializations of skill. By the "... division of labour and evolution of new crafts ..." (Cameron p.25) "tribal units became naturally isolated through time from the over-all developments in skill and technique present within their neighbouring environment. To utilize artifacts made by tribes specializing in areas of production not present to other tribes, exchange and trade became necessary."[8]

The first object or physical thing specifically used in a way similar enough to the modern definition of money, i.e. in exchange, was (probably) cattle (according to R.Davies).[9]

Trading in red ochre is attested in Swaziland, shell jewellery in the form of strung beads also dates back to this period, and had the basic attributes needed of commodity money. To organize production and to distribute goods and services among their populations, before market economies existed, people relied on tradition, top-down command, or community cooperation.

Antiquity: Bronze and Iron ages

See also : Ancient economic thought

Early developments in formal money and finance

See also : History of money

The city states of Sumer developed a trade and market economy based originally on the commodity money of the shekel which was a certain weight measure of barley, while the Babylonians and their city state neighbors later developed the earliest system of prices using a metric of various commodities that was fixed in a legal code.[10] The early law codes from Sumer could be considered the first (written) financial law, and had many attributes still in use in the current price system today; such as codified quantities of money for business deals (interest rates), fines for 'wrongdoing', inheritance rules, laws concerning how private property is to be taxed or divided, etc.[11] For a summary of the laws, see Babylonian law.

Temples are history's first documented creditors at interest, beginning in Sumer in the third millennium. By charging interest and ground rent on their own assets and property, temples helped legitimize the idea of interest‑bearing debt and profit seeking in general. Later, while the temples no longer included the handicraft workshops which characterized third‑millennium Mesopotamia, in their embassy functions they legitimized profit‑seeking trade, as well as by being a major beneficiary.[12]

Antiquity: Classical Era

India and China, the two largest economies respectively, accounted for more than half the size of the world economy.[13] Despite the high GDP, these nations being major population centers, did not have significantly higher GDP per capita.[14]

Expedition and long distance commerce

The two major changes in commercial activity due to expedition known by historical recounting, are those led by Alexander the Great,[15] which facilitated multi-national trade,[16] and the conquest to empire of Caesar (a Roman) of France and Britain.[17]

External trade with the Roman Empire

During the time of the trade of the Occident with Rome, Egypt was the wealthiest of all places within the Roman Empire. The merchants of Rome acquired produce from Persia through Egypt, by way of the port of Berenice, and subsequently the Nile.[18][19]

The introduction of coinage

According to Herodotus, and most modern scholars, the Lydians were the first people to introduce the use of gold and silver coin.[20] It is thought that these first stamped coins were minted around 650-600 BC.[21] A stater coin was made in the stater (trite) denomination. To complement the stater, fractions were made: the trite (third), the hekte (sixth), and so forth in lower denominations.

Developments in economic awareness and thought

The first economist (at least from within opinion generated by the evidence of extant writings) is considered to be Hesiod, by the fact of his having written on the fundamental subject of the scarcity of resources, in Works and Days .[22][23]

Greek and Roman thinkers made various economic observations, especially Aristotle and Xenophon. Many other Greek writings show understanding of sophisticated economic concepts. For instance, a form of Gresham’s Law is presented in Aristophanes’ Frogs.

Bryson of Heraclea was a neo-platonic who is cited as having heavily influenced early Muslim economic scholarship.[24]

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages the world economy slowly expanded with the increase of population and trade. The silk road was used for trading between Europe, Central Asia and China. During the early period of the Middle Ages, Europe was an economic backwater, however, by the later Medieval period rich trading cities in Italy emerged, creating the first modern accounting and finance systems.[25]

The first banknotes were used in Tang dynasty China in the ninth century (with expanded use during the Song dynasty),.

Early Modern Era

The Early modern era was a time of mercantilism, nationalism, and international trade. The waning of Feudalism saw new national economic frameworks begin to be strengthened. After the voyages of Christopher Columbus et al. opened up new opportunities for trade with the New World and Asia, newly-powerful monarchies wanted a more powerful military state to boost their status. Mercantilism was a political movement and an economic theory that advocated the use of the state's military power to ensure that local markets and supply sources were protected.

The first banknote in Europe was issued by Stockholms Banco in 1661.

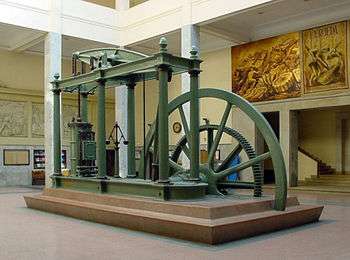

The Industrial Revolution

Economic history as it relates to economic growth in the modern sense first occurred during the Industrial Revolution in Europe, due to high amounts of energy conversion taking place.

The twentieth century

Economic growth spread to all regions of the world during the twentieth century, when world GDP per capita quintupled. The highest growth occurred in the 1960s during post-war reconstruction. Some increase in the volume of international trade is due to the reclassification of within-country trade to international trade – because of increasing number of countries and resulting changes in national boundaries. The effect is small.[27]

In particular, shipping containers revolutionized trade in the second half of the century, by making it cheaper to transport goods, especially internationally.[28]

Twenty-first century and the future

Global economic crisis

The world economy was predicted to shrink by between 0.5% and 1.0% in 2009, the first global contraction in 60 years. In its forecast the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said that developed countries will suffer "deep recession".[29]

See also

- Economics

- History of international trade

- Mode of production

- List of recessions

- List of countries by past GDP (PPP)

- History of the world

- Natural capital

- Energy economics

- Money

- Thermoeconomics

- Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt

- Technocracy (bureaucratic)

- Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World

References

- ↑ Scarre, Chris, ed. (2009). The Human Past (2nd ed.). Thames&Hudson. p. 32. ISBN 9780195127058.

- ↑ Cameron, Rondo; Neal, Larry (2003). A Concise Economic History of the World (4th Paperback ed.). Oxford. pp. 21–23. ISBN 9780195127058.

- ↑ Scarre, Chris, ed. (2009). The Human Past (2nd ed.). Thames&Hudson. pp. 171–173. ISBN 9780195127058.

- ↑ Aydon, Cyril (2007). A Brief History of Mankind. Robinson. pp. 10–20. ISBN 9781845297480.

- ↑ Hassan, Fekri A. (1981). Demographic Archeology. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123313508.

- ↑ http://delong.typepad.com/print/20061012_LRWGDP.pdf

- ↑ Vaswani, Padma, ed. (2012). Transitions (3 ed.). Vikas Publishing House Pvt Ltd.

- ↑ Rondo E.Cameron ( William Rand Kenan University Professor, Emory University in Atlanta, GA)Concise Economic History of the World: From Paleolithic Times to the Present Oxford University Press, 11 Mar 1993 Retrieved 2012-05-15

- ↑ Roy and Glyn Davies History of Money Exeter University and the University of Wales Press, Retrieved 2012-05-15

- ↑ http://history-world.org/reforms_of_urukagina.htm

- ↑ Charles F. Horne, Ph.D. (1915). "The Code of Hammurabi : Introduction". Yale University. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.appropriate-economics.org/materials/The_Early_Evolution_of_Interest-Bearing_Debt-Hudson.htm

- ↑ Maddison, Angus (2006). The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective (Vol. 1). Historical Statistics (Vol. 2). OECD. pp. 261, Table B–12. ISBN 92-64-02261-9.

- ↑ Maddison, Angus (2006). The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective (Vol. 1). Historical Statistics (Vol. 2). OECD. pp. 263, Table B–21. ISBN 92-64-02261-9.

- ↑ Quintus Curtius Rufus, William Henry Crosby Quintus Curtius Rufus: Life and exploits of Alexander the Great D. Appleton and Company, 1858 , Retrieved 2012-05-15

- ↑ Helmut Koester - Introduction to the New Testament: History, culture, and religion of the Hellenistic age Walter de Gruyter, 2000 ISBN 3110146924 Retrieved 2012-06-01

- ↑ John Pinkerton A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World: Many of which are Now First Translated Into English ; Digested on a New Plan, Volume 17 Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1814 Retrieved 2012-05-15

- ↑ Sir Richard Phillips New voyages and travels: consisting of originals, translations, and abridgments, Volume 1 printed for Sir Richard Phillips and Co. Retrieved 2012-05-15

- ↑ Charles Rollin The ancient history: containing the history of the Egyptians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Medes, Lydians, Carthaginians, Persians, Macedonians, the Seleucidae in Syria, and Parthians, Volume 1 Robert Carter, 1844 , Retrieved 2012-05-15

- ↑ Herodotus. Histories, I, 94

- ↑ http://rg.ancients.info/lion/article.html Goldsborough, Reid. "World's First Coin"

- ↑ Justin Ptak Institute for Business Cycle Research Retrieved 2012-05-16

- ↑ Tomáš Sedláček is a member of the National Economic Council in Prague (2011)Economics of Good and Evil: The Quest for Economic Meaning from Gilgamesh to Wall Street Oxford University Press, 1 Oct 2011Retrieved 2012-05-16

- ↑ Spengler (1964).

- ↑ http://www.economypoint.org/e/economics-in-the-middle-ages.html

- ↑ Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of into the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM (Madrid)

- ↑ Roser, Max; Crespo-Cuaresma, Jesus (2012). ""Borders Redrawn: Measuring the Statistical Creation of International Trade"". World Economy. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2012.01454.x.

- ↑ Marc Levinson The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and The World Economy Bigger Princeton University Press, 7 January 2008 Retrieved 2012-05-15

- ↑ "World economy 'to shrink in 2009'". BBC News. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.