Echiura

| Echiura Temporal range: Upper Carboniferous–Recent[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Urechis caupo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Echiura Newby, 1940[2] |

| Subdivision | |

| |

The Echiura, or spoon worms, are a small group of marine animals. Once treated as a separate phylum, they are now universally considered to represent derived annelid worms, which have lost their segmentation.[3][4][5][6] The majority of echiurans live in shallow water, but there are also deep sea forms. More than 230 species have been described.[7] The Echiura fossilise poorly and the earliest known specimen is from the Upper Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian). However, U-shaped fossil burrows that could be Echiuran have been found dating back to the Cambrian.

Distribution and habitat

Echiurans are exclusively marine and the majority of species live in the Atlantic Ocean. They are mostly infaunal, occupying burrows in the seabed, either in the lower intertidal zone or the shallow subtidal (e.g. the genera Echiurus, Urechis, and Ikeda). A few are found in deep waters including at abyssal depths.[8] They often accumulate in sediments with high concentrations of organic matter.

One species, Thalassema mellita, which lives off the southeastern coast of the US, inhabits the tests (exoskeleton) of dead sand dollars. When the worm is very small, it enters the test and later becomes too large to leave. In the 1970s, the spoon worm Listriolobus pelodes was found on the continental shelf off Los Angeles in numbers of up to 1,500 per square metre (11 square feet) near sewage outlets.[9] The burrowing and feeding activities of these worms churned up and aerated the sediment and promoted a balanced ecosystem with a more diverse fauna than would otherwise have existed in this heavily polluted area.[9]

Anatomy

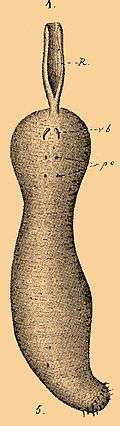

The bodies of spoon worms are generally cylindrical with two wider regions separated by a narrower region. There is a large extendible, scoop-shaped proboscis in front of the mouth which gives the animals their common name. This proboscis resembles that of peanut worms but it cannot be retracted into the body. It houses a brain and may be homologous to the prostomium of other annelids.[10] The proboscis is used for feeding and has rolled-in margins and a groove on the ventral surface. The distal end is sometimes forked. The proboscis can be very long; in the case of the Japanese species Ikeda taenioides, the proboscis can be 150 centimetres (59 in) long while the body is only 40 centimetres (16 in). Even smaller species like Bonellia can have a proboscis a metre (yard) long. Respiration also takes place through the proboscis although some larger species also use cloacal irrigation. In this process, water is pumped into and out of the rear end of the gut through the anus. The proboscis additionally has a sensory function.[11]

Compared with other annelids, echiurans have relatively few setae. In most species, there are just two, located on the underside of the body just behind the proboscis. In others, such as Echiurus, there are also further setae near the posterior end of the animal. Unlike other annelids, adult echiurans have no trace of segmentation.[10]

The body wall is muscular. It surrounds a large coelom which leads to a long looped intestine with an anus at the rear tip of the body.[12] The intestine is highly coiled, giving it a considerable length in relation to the size of the animal. A pair of simple or branched diverticula are connected to the rectum. These are lined with numerous minute ciliated funnels that open directly into the body cavity, and are presumed to be excretory organs.[10]

Echiurans do not have a distinct respiratory system, absorbing oxygen through the body wall.

Although some species lack a blood vascular system, where it is present, it resembles that of other annelids. The blood is essentially colourless, although some haemoglobin-containing cells are present in the coelomic fluid of the main body cavity. There can be anything from one to over a hundred metanephridia for excreting nitrogenous waste, which typically open near the anterior end of the animal.[10]

The nervous system consists of a brain near the base of the proboscis, and a ventral nerve cord running the length of the body. Aside from the absence of segmentation, this is a similar arrangement to that of other annelids. Echiurans do not have any eyes or other distinct sense organs.[10]

Most echiurans are a dull grey or brown but a few species are more brightly coloured, the translucent green Listriolobus pelodes being an example.[8]

A spoon worm can move from one location to another by extending its proboscis and grasping some object before pulling the body forward. Echiurus can also swim by use of the proboscis and by contractions of the body wall.[13]

Feeding

Typical spoon worms, including Bonellia, are suspension feeders, projecting their proboscis out of their burrows, with the gutter projecting upwards. Edible particles will then settle onto the proboscis and a ciliated channel conducts the food to the trunk.

Some spoon worms live in U-shaped tunnels in sand, mud or other soft substrate. Echiurus for example is a detritivore and extends its proboscis from the rim of its burrow with the ventral side on the substrate. The surface of the proboscis is well equipped with mucus glands to which food particles adhere. The mucus is bundled into boluses by cilia and these are passed along the feeding groove by cilia to the mouth. The proboscis is periodically withdrawn into the burrow and later extended in another direction.[8]

Urechis has a different method of feeding on detritus. It has a short proboscis and a ring of mucus glands at the front of its body. It expands its muscular body wall to deposit a ring of mucus on the burrow wall then retreats backwards, exuding mucus as it goes and spinning a mucus net. It then draws water through the burrow by peristaltic contractions and food particles stick to the net. When this is sufficiently clogged up, the spoon worm moves forward along its burrow devouring the net and the trapped particles. This process is then repeated and in a detritus-rich area may take only a few minutes to complete. Large particles are squeezed out of the net and are eaten by other invertebrates living commensally in the burrow. These typically include a small crab, a scale worm and often a fish lurking just inside the back entrance.[8]

Ochetostoma erythrogrammon obtains its food by another method. it has two vertical burrows connected by a horizontal one. Stretching out its proboscis across the substrate it shovels material into its mouth before separating the edible particles.[14] Other spoon worms conceal themselves in rock crevices, empty gastropod shells, sand dollar tests and similar places.[12] Some are scavengers or detritivores, while others are interface grazers and some are suspension feeders.[15]

While the proboscis of a spoon worm is on the surface it is at risk of predation by bottom-feeding fish. In some species the proboscis will autotomise (break off) if attacked and the worm will regenerate a proboscis over the course of a few weeks.[8]

Reproduction

Echiurans are dioecious, with separate male and female individuals. The gonads are associated with the peritoneal membrane lining the body cavity, into which they release the gametes. The sperm and eggs complete their maturation in the body cavity, before being released into the surrounding water through the metanephridia. Fertilization is external.[10]

Fertilized eggs hatch into free-swimming trochophore larvae. In some species, the larva briefly develops a segmented body before transforming into the adult body plan, supporting the theory that echiurans evolved from segmented ancestors resembling more typical annelids.[10]

The species Bonellia viridis, also remarkable for the possible antibiotic properties of bonellin, the green chemical in its skin, is unusual for its extreme sexual dimorphism. Females are typically 8 centimetres (3.1 in) in body length, excluding the proboscis, but the males are only 1 to 3 millimetres (0.039 to 0.118 in) long, and spend their lives within the uterus of the female.[10]

References

- ↑ Jones, D.; Thompson, I. D. A. (1977). "Echiura from the Pennsylvanian Essex Fauna of northern Illinois". Lethaia. 10 (4): 317. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1977.tb00627.x.

- ↑ Name authority

- ↑ Dunn, C. W.; Hejnol, A.; Matus, D. Q.; Pang, K.; Browne, W. E.; Smith, S. A.; Seaver, E.; Rouse, G. W.; Obst, M.; Edgecombe, G. D.; Sørensen, M. V.; Haddock, S. H. D.; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A.; Okusu, A.; Kristensen, R. M. B.; Wheeler, W. C.; Martindale, M. Q.; Giribet, G. (2008). "Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life". Nature. 452 (7188): 745–749. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..745D. doi:10.1038/nature06614. PMID 18322464.

- ↑ Bourlat, S.; Nielsen, C.; Economou, A.; Telford, M. (2008). "Testing the new animal phylogeny: A phylum level molecular analysis of the animal kingdom". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 49 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.07.008. PMID 18692145.

- ↑ Struck, T. H.; Paul, C.; Hill, N.; Hartmann, S.; Hösel, C.; Kube, M.; Lieb, B.; Meyer, A.; Tiedemann, R.; Purschke, G. N.; Bleidorn, C. (2011). "Phylogenomic analyses unravel annelid evolution". Nature. 471 (7336): 95–98. Bibcode:2011Natur.471...95S. doi:10.1038/nature09864. PMID 21368831.

- ↑ Struck, T. H.; Schult, N.; Kusen, T.; Hickman, E.; Bleidorn, C.; McHugh, D.; Halanych, K. M. (2007). "Annelid phylogeny and the status of Sipuncula and Echiura". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-57. PMC 1855331

. PMID 17411434.

. PMID 17411434. - ↑ Zhang, Z.-Q. (2011). "Animal biodiversity: An introduction to higher-level classification and taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148: 7–12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Walls, Jerry G. (1982). Encyclopedia of Marine Invertebrates. TFH Publications. pp. 262–267. ISBN 0-86622-141-7.

- 1 2 Stull, Janet K.; Haydock, C.Irwin; Montagne, David E. (1986). "Effects of Listriolobus pelodes (Echiura) on coastal shelf benthic communities and sediments modified by a major California wastewater discharge". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 22 (1): 1–17. Bibcode:1986ECSS...22....1S. doi:10.1016/0272-7714(86)90020-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 870–873. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ↑ Toonen, Rob (2012). "Part 6: Phylum Sipuncula and Phylum Annelida". Reefkeeper's Guide to Invertebrate Zoology. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- 1 2 Felty Light, Sol (1954). Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. Google Books. p. 108. ISBN 9780520007505. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ↑ "Echiuroidea". Encyclopedia Britannica 1911. Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- ↑ Chuang, S. H. (1962). "Feeding Mechanism of the Echiuroid, Ochetostoma erythrogrammon Leuckart & Rueppell, 1828". Biological Bulletin. 123 (1): 80–85. JSTOR 1539504.

- ↑ Echiuroidea World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Echiura. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Echiura |