Early life and work of Clint Eastwood

a series on Clint Eastwood |

|---|

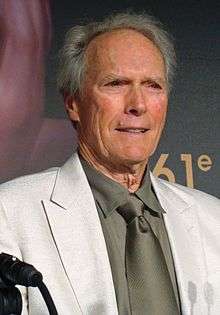

Clint Eastwood was born May 31, 1930 in San Francisco, California to Clinton Eastwood Sr. and Margaret Ruth (née Runner).

Early life

He was a large baby at 11 lb 6 oz (5.16 kg) and was named "Samson" by the nurses at the St. Francis Hospital.[1][2][3] Eastwood has English, Scottish, Dutch and Irish ancestry[4] and was raised in working-class Protestant homes in Oakland, Spokane, Washington and Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles along with his younger sister Jean. His father worked as a salesman and briefly a detective in San Francisco, according to U.S. Census records.[5][6] His family moved often, as his father worked at different jobs along the West Coast.[7] The family later settled in Piedmont, California, where Eastwood attended Piedmont Junior High School.

Eastwood was a bored student and records indicate he had to attend summer school.[8] Despite his athletic and musical talents, Eastwood shunned school teams and the band.[8] He was told he would make a good basketball player, but he was interested in individual pursuits like tennis and golf, a passion he retains today.[8] Shortly before he was to enter Piedmont High School, he rode his bike on the school's sports field and tore up the wet turf; this resulted in his being asked not to enroll.[9] Instead, he attended Oakland Technical High School, where the drama teachers encouraged him to take part in school plays, but was not interested. According to Eastwood, all he had on his mind were "fast cars and easy women".[10][11] He took auto mechanic courses and studied aircraft maintenance, rebuilding both aircraft and car engines.[11] Eastwood also became a pianist; according to a friend, he "would actually play the piano until his fingers were bleeding".[11]

By early 1949 his father moved to a plant in Seattle. Eastwood had to move in with a friend, Harry Pendleton, to finish high school in Oakland. He was invited to a house party in Malibu, where he met the film director Howard Hawks who, with John Ford, would influence his career.[12] Eastwood rejoined his family in Seattle, when he was 19, where he worked at the Weyerhaeuser Company pulp mill in Springfield, Oregon with his father.[13] He worked briefly as a lifeguard after obtaining a certificate from a Red Cross course,[14] and played ragtime piano at a bar in Oakland.

In 1951, Eastwood was drafted by the United States Army and assigned to Fort Ord in California, where he was appointed as a lifeguard and swimming instructor.[15] To supplement his $67 a month salary he held a part-time job on a loading dock for the Spreckels Sugar Refining Company. He visited Carmel for the first time and remarked "someday I'd like to live here", although he confessed he had gained unwanted attention from a 23-year-old school teacher, after a one-night stand, who stalked him and threatened to kill herself.[16]

In 30 September 1951, while returning from a weekend visit to his parents in Seattle, Eastwood was in the radar operator's compartment of an Douglas AD-1Q dive bomber that crashed into the Pacific Ocean off the Point Reyes Peninsula near San Francisco.[17][18] The aircraft had departed from Sand Point Naval Air Station near Seattle, bound for northern California.[n 1] During the flight, the rear door would not stay closed, the oxygen system proved inoperable, and the navigation systems and intercom failed. Eventually, during the late afternoon, the plane ran out of fuel and the pilot was forced to ditch the aircraft in the sea several miles off Point Reyes.[n 2] Both Eastwood and the pilot were uninjured and Eastwood was able to swim to shore unaided. He later reflected on his thoughts during the crash, "I thought I might die. But then I thought, other people have made it through these things before. I kept my eyes on the lights on shore and kept swimming."[19][17]

During his military service Eastwood became friends with future successful TV actors Richard Long, Martin Milner and David Janssen.[20]

Eastwood left Fort Ord in the spring of 1952 and moved back up to Seattle where he worked as a lifeguard for some time. However, as he had little money and few friends in Seattle, he moved down to Los Angeles.[21] During this time he worked managing an apartment house in Beverly Hills by day (into which he then moved) and worked at a Signal Oil gas station by night.[22][23] In June 1953, Eastwood met 22-year-old secretary Margaret Johnson and began dating her. They married shortly before Christmas 1953 in South Pasadena with friend Harry Pendleton as his best man, and honeymooned in Carmel.[22][24] After concluding his part-time work, he briefly attended Los Angeles City College and held several jobs digging foundations for residential swimming pools,[23] which he continued in between his early films.[25]

Early work

Becoming an actor

According to the CBS press release for Rawhide, Universal (known then as Universal-International) film company happened to be shooting in Fort Ord and an enterprising assistant spotted Eastwood and invited him to meet the director.[26] However, the key figure, according to his official biography was a man named Chuck Hill, who was stationed in Fort Ord and had contacts in Hollywood.[26] While in Los Angeles, Hill had reacquainted with Eastwood and with the help of an attractive telephone operator who took a shine to him, managed to succeed in sneaking Eastwood into a Universal studio and showed him to cameraman Irving Glassberg.[26] Glassberg was impressed with his appearance and stature and believed him to be, "the sort of good looking young man that has traditionally done well in the movies".[26]

Glassberg arranged for director Arthur Lubin to meet Eastwood at the gas station where he was working in the evenings in Los Angeles.[26] Lubin, like Glassberg was highly impressed, remarking, "so tall and slim and very handsome looking".[27] He swiftly arranged for Eastwood's first audition but was rather less enthusiastic, remarking, "He was quite amateurish. He didn't know which way to turn or which way to go or do anything".[27] Neverless, he told Eastwood not to give up, and suggested he attend drama classes, and later arranged for an initial contract for Eastwood in April 1954 at $100 a week.[27] Some people in Hollywood, including his wife Maggie, were suspicious of Lubin's intentions towards Eastwood; he was homosexual and maintained a close friendship with Eastwood in the years that followed.[28] After signing, Eastwood was required to perform in front of staff members, including actress Myrna Hansen. He played Alan Squier, a disillusioned English intellectual from The Petrified Forest and in one scene was required to strip in front of the Universal staff.[29] He was initially criticised for his speech and awkward manner; he was soft-spoken and in performing in front of people was cold, stiff and awkward.[30] Fellow talent school actor John Saxon, described Eastwood as, "being like a kind of hayseed.. Thin, rural, with a prominent Adam's Apple, very laconic and slow speechwise."[31] The new trainee was certainly not naturally disposed to being a leading man. He lacked creative imagination in the improvisations and although he had a sense of humor and was successful with women off screen, it did not transcend into his early acting.[31]

Universal Studios: Training and development

In May 1954, Eastwood made his first real audition, trying out for a part in Six Bridges to Cross, a film about the Brinks robbery that would mark the debut of actor Sal Mineo. Director Joseph Pevney was not impressed by his acting and rejected him for any role.[31] Later he tried out for Brigadoon, The Constant Nymph, Bengal Brigade and The Seven Year Itch in May 1954, Sign of the Pagan (June), Smoke Signal (August) and Abbott and Costello Meet the Keystone Kops (September), all without success.[31] Eastwood was eventually given a minor role by director Jack Arnold in the film Revenge of the Creature, a film set in the Amazon jungle, which was the sequel to The Creature from the Black Lagoon which had been released just months earlier.[32] Eastwood played the role of Jennings, a white-coated lab technician who assists the doctor (John Agar) in researching the "creature" and has a liking to white rats used in testing, keeping one in his pocket. His scene was shot in one day on Friday, July 30, 1954 at Stage No. 16 in Universal, although much of the rest of the film was shot at Marineland south of St Augustine, Florida.[33]

Following this, Eastwood and his wife moved into an apartment at Villa Sands at 4040 Arch Drive off Ventura Boulevard to be closer to the Universal lot, also occupied by fellow Universal actresses Gia Scala and Lili Kardell.[34] It also gave Eastwood an opportunity to continue his swimming as it had notable swimming facilities, and the apartment block became a venue for many swimsuit photo shoots, including a memorable one of Anita Ekberg in a leopard skin bikini.[34] In 1954, he agreed to play the part of a scarecrow in the annual Christmas musical for children of employees of Universal studio.[35] Meanwhile, Eastwood was coached by Jess Kimmel and Jack Kosslyn, and UCLA professor, Dr. Daniel Vandraegen who specialized in correcting bad speech. Eastwood had an early tendency to speak almost in a sibilant whisper and was advised to project his voice. These traits never fully went away, but actually worked in his favor in his later films, especially as the Man with No Name in which he often hissed his lines through clenched teeth.[35] Although Clint was self-conscious on camera, he demonstrated a strength in displaying anger onscreen, and in one improvised scene during training with Betty Jane Howarth, it left her in tears.[36]

At this time, Eastwood was likened to Gary Cooper and he resembled a tall, rangy version of James Dean with his high forehead and unruly quiff.[37] Eastwood was a great admirer of Dean and his rebel image.[37] However, one day he was introduced to James Dean at Lili Kardell's apartment and Dean showed little enthusiasm, prompting Eastwood to yank him to his feet and snort, "Goddamn it, fellow, stand up when I speak to you", although he was apparently kidding.[37] Eastwood also met Charlton Heston for the first time at a gym, mistaking him for Chuck Connors.[38]

In September 1955, Eastwood worked for three weeks on Arthur Lubin's Lady Godiva of Coventry in which he donned a medieval costume, and then in February 1955, won a role playing "Jonesy", a sailor in Francis in the Navy and his salary was raised to $300 a week for the four weeks of shooting.[39] He again appeared in a Jack Arnold film, Tarantula, with a small role as a squadron pilot, again uncredited.[40] In May 1955, Eastwood put four hours work into the film Never Say Goodbye, in which he again played a white-coated technician uttering a single line, and again had a minor uncredited role as a ranch hand (his first western film) in August 1955 with Law Man, also known as Stars in the Dust.[41] He gained experience behind the set, watching productions and dubbing and editing sessions of other films at Universal Studios, notably the Montgomery Clift/Elizabeth Taylor/Shelley Winters film A Place in the Sun.[41] Universal presented him with his first TV role with a small television debut on NBC's Allen in Movieland on July 2, 1955, starring actor Tony Curtis and musician Benny Goodman.[42] Although his records at Universal revealed his development, Universal terminated his contract on October 25, 1955, leaving Eastwood gutted and blaming casting director Robert Palmer, on whom he would exact revenge years later. When Palmer came looking for employment at his Malpaso Company, Eastwood rejected him.[43]

Uncredited Bit Parts in B-films

On the recommendation of Betty Jane Howarth, Eastwood soon joined new publicity representatives, the Marsh Agency, who had represented actors such as Adam West and Richard Long.[28] Although Eastwood's contract with Lubin had ended, he was important in landing Eastwood his biggest role to date; a featured role in the Ginger Rogers and Carol Channing western comedy, The First Traveling Saleslady.[44] Eastwood played a recruitment officer for Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders. He would also play a pilot in another of Lubin's productions, Escapade in Japan and would make several TV appearances under Lubin even into the early 1960s.[44] As Eastwood grew in success, he never spoke to Lubin again until 1992, shortly after winning his Oscar for Unforgiven, when Eastwood promised a lunch that never happened.[44]

Without the contract of Lubin in the meantime, however, Eastwood was struggling.[44] He was advised by Irving Leonard financially and under his influence changed talent agencies in rapid succession, the Kumin-Olenick Agency in 1956, and Mitchell Gertz in 1957. He landed a small role as temperamental army officer for a segment of ABC's Reader's Digest series, broadcast in January 1956, and later that year, a motorcycle gang member on a Highway Patrol episode.[44] In 1957, Eastwood played a cadet who becomes involved in a skiing search and rescue in the 'White Fury' installment of the West Point series. He also appeared in an episode of the prime time series Wagon Train and a suicidal gold prospector in Death Valley Days.[45] In 1958 he played a Navy lieutenant in a segment of Navy Log and in early 1959 made a notable guest appearance as a cowardly villain, intent on marrying a rich girl for money, in Maverick.[45]

During this period, Eastwood applied for assorted day jobs, dug pools and began working out hard in the gym.[45] He attended further acting classes held by Jack Kosslyn whose students also included people like Nick Adams, Irish McCalla, Jamie Farr and Jeanne Baird and other developing actors. Eastwood also displayed an early toughness in real life when on one evening Eastwood, his wife, Floyd Simmons and another couple had gone to dinner at Trader Vic's and were threatened at gunpoint before entering the restaurant by a gang of Latin thugs. Although his friends turned to flee, Clint stood his ground and growled, "Go on and pull that trigger, you little son of a bitch, and I'll kill you before I hit the ground".[46] The thugs ran off.[46] On another occasion, Clint and friend Fritz Manes were at a bar on Highland Avenue where Clint's long, wavy hair caught the attention of a group of sailors who taunted him and called him a "Hollywood faggot".[46] One of them landed a punch to Eastwood's face, but Eastwood surprised them, putting two of the men in hospital and injuring the others.[47]

Eastwood was credited for his roles in several more films. He auditioned for the film The Spirit of St. Louis, a Billy Wilder biopic about aviator Charles Lindbergh. He was rejected and the role in the end went to Jimmy Stewart who just put on makeup to make him look younger. He did however have a small part as an aviator in the French picture Lafayette Escadrille, and played an ex-renegade in the Confederacy in Ambush at Cimarron Pass, his biggest screen role to date opposite Scott Brady. His part was shot in nine days for Regal Films Inc. Out of frustration, he dismissed the film as "probably the lousiest Western ever made", and said, "It was sooo bad. I just kept sinking lower and lower in my seat and just wanted to quit".[48] Around the time the film was released Eastwood described himself as feeling "really depressed" and regards it as the lowest point in his career.[48] He seriously considered quitting the acting profession and returning to school to start doing something with his life.[48]

Rawhide (1959–1966)

Floyd Simmons recommended that Eastwood sign with his agent Bill Shiffrin, a hard man, noted for his work with other young, muscular actors. Shiffrin informed Clint that CBS were casting an hour-long Western series and urged him to attend the studio. There he met up with Sonia Chernus, a story editor now working for NBC and while conversing with her, an executive, Robert Sparks, spotted Eastwood in the canteen. The first thing he said was, "How tall are you exactly"? Clint replied, "6'4".[49] The executive invited him into his office and later arranged for a screen test with Charles Marquis Warren overlooking, in which Eastwood had to recite one of Henry Fonda's monologues from the William Wellman western, The Ox-Bow Incident.[50] A week later, Shiffrin rang Eastwood and informed him he had won the part of Rowdy Yates in Rawhide. He had successfully beaten competition such as Bing Russell and had got the break he had been looking for.[50]

Filming began in Arizona in the summer of 1958. His rivalry onscreen with Eric Fleming's character, Gil Favor, was reportedly initially echoed offscreen between the two actors. However, Eastwood has denied that the two ever had a scuffle and especially after Fleming's death by drowning in Peru some years later, has revealed he had much respect for his co-star.[51] The writer, Charles Marquis Warren, however, described Eastwood's co-star as, "a miserable human being, not only a lousy performer but a colossal egotist".[52] Although Eastwood was finally pleased with the direction of his career, he was not especially happy with the nature of his Rowdy Yates character. At this time, Eastwood was 30, and Rowdy was too young and too cloddish for Clint to feel comfortable with the part. Although boyishness was a key element in his casting, Eastwood disliked the juvenile overtones of the character and privately described Yates as "the idiot of the plains"[53] According to co-star Paul Brinegar, who played Wishbone, Eastwood was, "very unhappy about playing a teenager type".[54]

Eastwood soon ended his contract with Bill Shiffrin and hired Lester Salkow as his talent agent between 1961 and 1963. In regards to his contracts though, it was Irving Leonard and the attorney Frank Wells who played an important role. They structured Eastwood's earnings, (now at $750 per episode) to avoid paying undue taxes and guaranteed the paychecks from CBS well into the future.[55] Leonard in particular tightly controlled his finances to the extent that when he wanted to buy a car he had to request permission.[56] He and Maggie continued to live inexpensively but bought a home in Sherman Oaks off Beverly Glen, a modest hillside ranch. His first interview with TV Guide for Rawhide came in August 1959 in which they concentrated on his physical fitness, taking photographs of him doing pushups at home as Eastwood advised readers to keep in shape, warned against carbohydrates and recommended skipping beverages loaded with sugar and eating plenty of fruit and vegetables and vitamins.[57]

It took just three weeks for Rawhide to reach the top 20 in the TV ratings and soon rescheduled the timeslot half an hour earlier from 7.30 -8.30 pm every Friday, guaranteeing more of a family audience.[58] For several years it was a major success, and reached its peak as number 6 in the ratings between October 1960 and April 1961.[58] However, success was not without its price. The Rawhide years were undoubtedly the most grueling of his life, and at first, from July until April, they filmed six days a week for an average of twelve hours a day.[58] Although it never won Emmy stature, Rawhide earned critical acclaim and won the American Heritage Award as the best Western series on TV and it was nominated several times for best episode by the Writer's and Director's Guilds.[58] However, the quality of the storylines in each episode ranged dramatically from the brutal and subjects such as gypsy curses to predictable, silly comedy.[58] Eastwood during this period received some criticism and was considered too laid back by some directors who believed he relied on his looks and just didn't work hard enough.[59] Gene Fowler Jr. described Clint as "lackadaisical" in his attitude, whilst one of the series' most prolific crewmen, Tommy Carr described him as, "lazy, and would cost you a morning. I never started a day with Clint Eastwood in the first scene, because you knew he was gonna be late, at least a half hour or an hour."[59] Laziness, ironically, would later work in his favor and attract the attention of Italian director Sergio Leone and launch Eastwood's successful career in film. Karen Sharpe, an actress, explained the laziness might have been because of his womanizing and would often disappear into his trailer with a lady friend (despite being married) and after having sex, he'd be too tired to do his afternoon scenes.[59] Although Eastwood did demonstrate growing abilities as an actor, developing an ability to demonstrate surprising authority and balancing humor with emotional nuance, he was not much noticed for his acting abilities at the time.[60]

Despite his busy schedule, soon after singing A Drover's Life on Rawhide and later Beyond the Sun, Eastwood would have a strong desire to pursue his major passion, music. Although jazz was his main interest, he was also a country and western enthusiast.[61] He went into the studio and by late 1959 had produced the album Cowboy Favorites which was released on the Cameo label.[61] The album included some classics such as Bob Wills's San Antonio Rose and Cole Porter's Don't Fence Me In and despite his attempts to plug the album by going on a tour, it never reached the Billboard Hot 100.[61] Later in 1963, Cameo producer Kal Mann would bluntly tell him that "he would never make it big as a singer".[62] Nevertheless, during the off season of filming Rawhide, Eastwood and Brinegar, sometimes joined by Sheb Wooley would go on touring rodeos, state fairs and festivals and in 1962 their act entitled Amusement Business Cavalcade of Fairs earned them as much as $15,000 a performance.[62] Brinegar also accompanied Eastwood on his first trip outside the country in early 1962 to Japan to increase their publicity, leaving his wife at home.

By the third season of Rawhide, the Hollywood press began to speculate on Eastwood tiring of the series and that he was anxious to move on. A July 1961 article by Hank Grant in the Hollywood Reporter described him as, "Calm on the outside and boiling on the inside" and played upon Eastwood's apparent frustration that he hadn't been able to accept a single feature since joining the CBS series because of his contract, and he had said, "Maybe they really figure me as the sheepish, nice guy I portray in the series, but even a worm has to turn sometime."[63] Eastwood did, however, make several guest appearance in the meantime on TV, including a cameo in Mr Ed poking fun at himself as a neighbor of Mr. Ed in an episode directed by his old mentor Arthur Lubin and the western comedy series Maverick, in which he fought James Garner in the "Duel at Sundown" episode. Although Rawhide continued to attract notable actors such as Lon Chaney Jr, Mary Astor, Ralph Bellamy, Burgess Meredith, Dean Martin and Barbara Stanwyck, by late 1963 Rawhide was beginning to decline in popularity and lacked freshness in the script.[64] In regards to the character of Rowdy Yates, he had evolved to upstage that of Gil Favor and became increasingly tough like him, not a trait in which his character had begun. Rawhide would last until 1966, but a change of direction in Eastwood's career would occur in late 1963.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Different sources report different intended destinations. Schickel says it was Alameda Naval Air Station near Oakland. Zmijewsky says it was Mather Air Force Base at Sacramento. The Navy's accident report says it was San Diego, with a stop at McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento.

- ↑ Accounts of the crash location also differ slightly. Schickel says "they could see the cliffs at Point Reyes, three or four miles away. Zmijewsky says it was north of Drake's Bay and two miles offshore. The Navy's accident report indicates that it was west of Kehoe Beach.

References

- ↑ Schickel 1996, p. 21.

- ↑ guardian.co.uk Gentle man Clint, November 2, 2008.

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 22

- ↑ Smith, Paul (1993). Clint Eastwood a Cultural Production. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1958-1.

- ↑ adherents.com The Religious Affiliation of actor/director Clint Eastwood.

- ↑ Zmijewsky, p. 13

- ↑ CBS Evening News interview, February 6, 2005.

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 34

- ↑ Kilduff, Paul (September 2012). "The Principal of the Thing: Piedmont High's head honcho on texting, fear, and Rawhide". The East Bay Monthly. 42 (12): 18. Interview of Richard Kitchens.

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 35

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 37

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.41

- ↑ The King of Western Swing - Bob Wills Remembered. Rosetta Wills. 1998. p. 165 ISBN 0-8230-7744-6.

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.43

- ↑ Eliot, p. 23

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), pp. 48–49

- 1 2 Schickel 1996, pp. 51–55.

- ↑ "Accident Report: AD-1Q BU#409283 Eastwood". U.S. Navy. 1951.

- ↑ Zmijewsky (1982), p. 16

- ↑ Schickel 1996, p. 50.

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.54

- 1 2 McGillagan (1999), p. 55

- 1 2 Zmijewsky (1982), p. 17

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 56

- ↑ Zmijewsky (1982), p. 19

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGillagan (1999), p. 52

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 60

- 1 2 McGillagan (1999), p.84

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.61

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 62

- 1 2 3 4 McGillagan (1999), p. 63

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 64

- ↑ http://www.marineland.net/history/php

- 1 2 McGillagan (1999), pp. 65–66

- 1 2 McGillagan (1999), p. 72

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.77

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 73

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 78

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 79

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 80

- 1 2 McGillagan (1999), p. 81

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.86

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), pp. 82–3

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGillagan (1999), p. 85

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 87

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 90

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 91

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 93

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 94

- 1 2 McGillagan (1999), p. 95

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 100

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 101

- ↑ Reader's Digest Australia: RD Face to Face: Clint Eastwood.

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.102

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.104

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.105

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.108

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGillagan (1999), p. 110

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 111

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 113

- 1 2 3 McGillagan (1999), p. 114

- 1 2 McGillagan (1999), p. 115

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 124

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p. 125

Bibliography

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- Schickel, Richard (1996). Clint Eastwood: A Biography. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-42974-6.

- Zmijewsky, Boris; Lee Pfeiffer (1982). The Films of Clint Eastwood. Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-0863-9.