Lutein

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

β,ε-carotene-3,3'-diol | |

| Other names

Luteine; trans-lutein; 4-[18-(4-Hydroxy-2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohexenyl)-3,7,12,16-tetramethyloctadeca-1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15,17-nonaenyl]-3,5,5-trimethyl-cyclohex-2-en-1-ol | |

| Identifiers | |

| 127-40-2 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28838 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL173929 |

| ChemSpider | 4444655 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.401 |

| E number | E161b (colours) |

| PubChem | 5281243 |

| UNII | X72A60C9MT |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

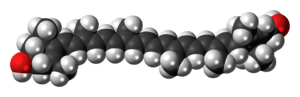

| C40H56O2 | |

| Molar mass | 568.871 g/mol |

| Appearance | Red-orange crystalline solid |

| Melting point | 190 °C (374 °F; 463 K)[1] |

| Insoluble | |

| Solubility in fats | Soluble |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Lutein (/ˈluːtiː.ᵻn/ or /ˈluːtiːn/;[2] from Latin luteus meaning "yellow") is a xanthophyll and one of 600 known naturally occurring carotenoids. Lutein is synthesized only by plants and like other xanthophylls is found in high quantities in green leafy vegetables such as spinach, kale and yellow carrots. In green plants, xanthophylls act to modulate light energy and serve as non-photochemical quenching agents to deal with triplet chlorophyll (an excited form of chlorophyll), which is overproduced at very high light levels, during photosynthesis. See xanthophyll cycle for this topic.

Lutein is obtained by animals directly or indirectly, from plants. Lutein is apparently employed by animals as an antioxidant and for blue light absorption. Lutein is found in egg yolks and animal fats. In addition to coloring yolks, lutein causes the yellow color of chicken skin and fat, and is used in chicken feed for this purpose. The human retina accumulates lutein and zeaxanthin. The latter predominates at the macula lutea while lutein predominates elsewhere in the retina. There, it may serve as a photoprotectant for the retina from the damaging effects of free radicals produced by blue light. Lutein is isomeric with zeaxanthin, differing only in the placement of one double bond.

The principal natural stereoisomer of lutein is (3R,3′R,6′R)-beta,epsilon-carotene-3,3′-diol. Lutein is a lipophilic molecule and is generally insoluble in water. The presence of the long chromophore of conjugated double bonds (polyene chain) provides the distinctive light-absorbing properties. The polyene chain is susceptible to oxidative degradation by light or heat and is chemically unstable in acids.

Lutein is present in plants as fatty-acid esters, with one or two fatty acids bound to the two hydroxyl-groups. For this reason, saponification (de-esterfication) of lutein esters to yield free lutein may yield lutein in any ratio from 1:1 to 1:2 molar ratio with the saponifying fatty acid.

As a pigment

This xanthophyll, like its sister compound zeaxanthin, has primarily been used as a natural colorant due to its orange-red color. Lutein absorbs blue light and therefore appears yellow at low concentrations and orange-red at high concentrations.

Lutein is also anti angiogenic. It inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Lutein was traditionally used in chicken feed to improve the color of broiler chicken skin. Polled consumers viewed yellow chicken skin more favorably than white chicken skin. Such lutein fortification also results in a darker yellow egg yolk. Today the coloring of the egg yolk has become the primary reason for feed fortification. Lutein is not used as a colorant in other foods due to its limited stability, especially in the presence of other dyes.

Role in human eyes

Lutein was found to be concentrated in the macula, a small area of the retina responsible for 3-Dimensional vision. The hypothesis for the natural concentration is that lutein helps keep the eyes safe from oxidative stress and the high-energy photons of blue light. Various research studies have shown that a direct relationship exists between lutein intake and pigmentation in the eye.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Lutein may play a role in Haidinger's brush, an entoptic phenomenon that allows humans to detect polarized light.

Macular degeneration

Several studies show that an increase in macula pigmentation decreases the risk for eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).[10][11][12] The only randomized clinical trial to demonstrate a benefit for lutein in macular degeneration was a small study, in which the authors concluded that visual function is improved with lutein alone or lutein together with other nutrients and also that more study was needed.[11]

There is epidemiological evidence of a relationship between low plasma concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin, and an increased risk of developing age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Some studies support the view that supplemental lutein and/or zeaxanthin help protect against AMD.[13]

In 2007, in a six-year study, John Paul SanGiovanni of the National Eye Institute, Maryland, found that lutein and zeaxanthin protect against blindness (macular degeneration), affecting 1.2 million Americans, mostly after age 65. Lutein and zeaxanthin reduce the risk of AMD.[13]

In 2013, findings of the Age-related Eye Disease Study 2 were reported in JAMA; AREDS2 was a five-year study designed to test whether the original AREDS formulation that was shown to reduce progression of age-related macular degeneration by 25 percent would be improved by adding omega-3 fatty acids; adding lutein and zeaxanthin; removing beta-carotene; or reducing zinc.[14] In AREDS2, participants took one of four AREDS formulations: the original AREDS formulation, AREDS formulation with no beta-carotene, AREDS with low zinc, AREDS with no beta-carotene and low zinc.[14] In addition, they took one of four additional supplement or combinations including lutein and zeaxanthin (10 mg and 2 mg), omega-3 fatty acids (1,000 mg), lutein/zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids, or placebo.[14] The study reported that there was no overall additional benefit from adding omega-3 fatty acids or lutein and zeaxanthin to the formulation.[14] However, the study did find benefits in two subgroups of participants: those not given beta-carotene, and those who had very little lutein and zeaxanthin in their diets.[14] Removing beta-carotene did not curb the formulation's protective effect against developing advanced AMD, which was important given that high doses of beta-carotene had been linked to higher risk of lung cancers in smokers.[14] It was recommended to replace beta-carotene with lutein and zeaxanthin in future formulations for these reasons.[14]

Cataracts

There is also epidemiological evidence that increasing lutein and zeaxanthin intake lowers the risk of cataract development.[13][15] Consumption of more than 2.4 mg of lutein/zeaxanthin daily from foods and supplements was significantly correlated with reduced incidence of nuclear lens opacities, as revealed from data collected during a 13- to 15-year period in the Nutrition and Vision Project (NVP).[16]

Photophobia (abnormal human optical light sensitivity)

A study by Stringham and Hammond, published in the January/February 2010 issue of Journal of Food Science, discusses the improvement in visual performance and decrease in light sensitivity (glare) in subjects taking 10 mg lutein and 2 mg zeaxanthin per day.[17]

In nutrition

Lutein is a natural part of human diet when fruits and vegetables are consumed. For individuals lacking sufficient lutein intake, lutein-fortified foods are available, or in the case of elderly people with a poorly absorbing digestive system, a sublingual spray is available. As early as 1996, lutein has been incorporated into dietary supplements. While no recommended daily allowance currently exists for lutein as for other nutrients, positive effects have been seen at dietary intake levels of 6–10 mg/day.[18] The only definitive side effect of excess lutein consumption is bronzing of the skin (carotenodermia).

The functional difference between lutein (free form) and lutein esters is not entirely known. It is suggested that the bioavailability is lower for lutein esters, but much debate continues.[19]

As a food additive, lutein has the E number E161b (INS number 161b) and is extracted from the petals of marigold (Tagetes erecta).[20] It is approved for use in the EU[21] and Australia and New Zealand[22] but is banned in the USA.

Some foods are considered good sources of the nutrients:[13][23][24][25]

| Product | Lutein/zeaxanthin (micrograms per hundred grams) |

|---|---|

| nasturtium (yellow flowers, lutein levels only) | 45,000 [25] |

| kale (raw) | 39,550 |

| kale (cooked) | 18,246 |

| dandelion leaves (raw) | 13,610 |

| nasturtium (leaves, lutein levels only) | 13,600 [25] |

| turnip greens (raw) | 12,825 |

| spinach (raw) | 12,198 |

| spinach (cooked) | 11,308 |

| swiss chard (raw or cooked) | 11,000 |

| turnip greens (cooked) | 8440 |

| collard greens (cooked) | 7694 |

| watercress (raw) | 5767 |

| garden peas (raw) | 2593 |

| romaine lettuce | 2312 |

| zucchini | 2125 |

| brussels sprouts | 1590 |

| pistachio nuts | 1205 |

| broccoli | 1121 |

| carrot (cooked) | 687 |

| Maize/corn | 642 |

| egg (hard boiled) | 353 |

| avocado (raw) | 271 |

| carrot (raw) | 256 |

| kiwifruit | 122 |

Safety

In humans, the Observed Safe Level (OSL) for lutein is 20 mg/day.[26] Although much higher levels have been tested without adverse effects and may also be safe, the data for intakes above the OSL are not sufficient for a confident conclusion of long-term safety.[26]

In mice, the LD50 exceeded the highest tested dose of 10 g/kg of body weight, and the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) was determined as 1 g/kg/day, also the highest dose tested.[27]

Commercial value

The lutein market is segmented into pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, food, pet foods, and animal and fish feed.

- The pharmaceutical market is estimated to be about US$190 million, nutraceutical and food is estimated to be about US$110 million.

- Pet foods and other applications are estimated at US$175 million annually.

Apart from the customary age-related macular degeneration applications, newer applications are emerging in cosmetics, skin care area as an antioxidant. It is one of the fastest growing areas of the US$2 billion carotenoid market.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ MSDS at Carl Roth (Lutein Rotichrom, German).

- ↑ "lutein", Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ Malinow MR, Feeney-Burns L, Peterson LH, Klein ML, Neuringer M (August 1980). "Diet-related macular anomalies in monkeys". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 19 (8): 857–63. PMID 7409981.

- ↑ Johnson EJ, Hammond BR, Yeum KJ (June 2000). "Relation among serum and tissue concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin and macular pigment density". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71 (6): 1555–62. PMID 10837298.

- ↑ Landrum, J., et al. Serum and macular pigment response to 2.4 mg dosage of lutein. in ARVO. 2000.

- ↑ Berendschot TT, Goldbohm RA, Klöpping WA, van de Kraats J, van Norel J, van Norren D (October 2000). "Influence of lutein supplementation on macular pigment, assessed with two objective techniques". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41 (11): 3322–6. PMID 11006220.

- ↑ Aleman TS, Duncan JL, Bieber ML (July 2001). "Macular pigment and lutein supplementation in retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42 (8): 1873–81. PMID 11431456.

- ↑ Duncan JL, Aleman TS, Gardner LM (March 2002). "Macular pigment and lutein supplementation in choroideremia". Exp. Eye Res. 74 (3): 371–81. doi:10.1006/exer.2001.1126. PMID 12014918.

- ↑ Johnson EJ, Neuringer M, Russell RM, Schalch W, Snodderly DM (February 2005). "Nutritional manipulation of primate retinas, III: Effects of lutein or zeaxanthin supplementation on adipose tissue and retina of xanthophyll-free monkeys". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46 (2): 692–702. doi:10.1167/iovs.02-1192. PMID 15671301.

- ↑ Richer S (January 1999). "ARMD—pilot (case series) environmental intervention data". J Am Optom Assoc. 70 (1): 24–36. PMID 10457679.

- 1 2 Richer S, Stiles W, Statkute L (April 2004). "Double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of lutein and antioxidant supplementation in the intervention of atrophic age-related macular degeneration: the Veterans LAST study (Lutein Antioxidant Supplementation Trial)". Optometry. 75 (4): 216–30. doi:10.1016/s1529-1839(04)70049-4. PMID 15117055.

- ↑ Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group (October 2001). "A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8". Arch. Ophthalmol. 119 (10): 1417–36. doi:10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. PMC 1462955

. PMID 11594942.

. PMID 11594942. - 1 2 3 4 SanGiovanni JP, Chew EY, Clemons TE (September 2007). "The relationship of dietary carotenoid and vitamin A, E, and C intake with age-related macular degeneration in a case-control study: AREDS Report No. 22". Arch. Ophthalmol. 125 (9): 1225–32. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.9.1225. PMID 17846363.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 http://www.nei.nih.gov/news/pressreleases/050513.asp

- ↑ "Associations between age-related nuclear cataract and lutein and zeaxanthin in the diet and serum in the Carotenoids in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, an Ancillary Study of the Women's Health Initiative.".

- ↑ Barker Fm, 2nd (2010). "Dietary supplementation: effects on visual performance and occurrence of AMD and cataracts.". Current medical research and opinion. 26 (8): 2011–23. doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.494549. PMID 20590393.

- ↑ Stringham, James M.; et al. (January–February 2010). "The Influence of Dietary Lutein and Zeaxanthin on Visual Performance". Journal of Food Science. 75 (1): R24–R29. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01447.x. PMID 20492192. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ↑ Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD (November 1994). "Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group". JAMA. 272 (18): 1413–20. doi:10.1001/jama.272.18.1413. PMID 7933422.

- ↑ Bowen PE, Herbst-Espinosa SM, Hussain EA, Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis M (2002). "Esterification does not impair lutein bioavailability in humans". J Nutr. 132 (12): 3668–73. PMID 12468605.

- ↑ WHO/FAO Codex Alimentarius General Standard for Food Additives

- ↑ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ↑ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code"Standard 1.2.4 - Labelling of ingredients". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ↑ Reuters, Study finds spinach, eggs ward off cause of blindness

- ↑ USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 23 (2010)

- 1 2 3 Niizu, P.Y.; Delia B. Rodriguez-Amaya (2005). "Flowers and Leaves of Tropaeolum majus L. as Rich Sources of Lutein". Journal of Food Science. 70 (9): S605–S609. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb08336.x. ISSN 1750-3841.

- 1 2 Shao A, Hathcock JN (2006). "Risk assessment for the carotenoids lutein and lycopene". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology : RTP. 45 (3): 289–98. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.05.007. PMID 16814439. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

The OSL risk assessment method indicates that the evidence of safety is strong at intakes up to 20mg/d for lutein, and 75 mg/d for lycopene, and these levels are identified as the respective OSL. Although much higher levels have been tested without adverse effects and may be safe, the data for intakes above these levels are not sufficient for a confident conclusion of long-term safety.

- ↑ Nidhi B, Baskaran V (2013). "Acute and subacute toxicity assessment of lutein in lutein-deficient mice" (PDF). Journal of Food Science. 78 (10): T1636–42. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12256. PMID 24024482. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

Preliminary acute toxicity study revealed that the LD50 exceeded the highest dose of 10000 mg/kg BW. In a subacute study, male mice were gavaged with 0, 100, 1000 mg/kg BW/day for a period of 4 wk. Plasma lutein levels increased dose dependently (P < 0.01) after acute and subacute feeding of lutein in LD mice. Compared to the control (peanut oil without lutein) group, no treatment-related toxicologically significant effects of lutein were prominent in clinical observation, ophthalmic examinations, body, and organ weights. Further, no toxicologically significant findings were eminent in hematological, histopathological, and other clinical chemistry parameters. In the oral subacute toxicity study, the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) for lutein in LD mice was determined as 1000 mg/kg/day, the highest dose tested.

- ↑ FOD025C The Global Market for Carotenoids, BCC Research