Du Shi

Du Shi (Chinese: 杜詩; pinyin: Dù Shī; Wade–Giles: Tu Shih, d. 38[1][2]) was a Chinese governmental Prefect of Nanyang in 31 AD and a mechanical engineer of the Eastern Han Dynasty in ancient China. Du Shi is credited with being the first to apply hydraulic power (i.e. a waterwheel) to operate bellows (air-blowing device) in metallurgy. His invention was used to operate piston-bellows of the blast furnace and then cupola furnace in order to forge cast iron, which had been known in China since the 6th century BC. He worked as a censorial officer and administrator of several places during the reign of Emperor Guangwu of Han. He also led a brief military campaign in which he eliminated a small bandit army under Yang Yi (d. 26).

Life

Early career

Although the year of his birth is uncertain, it is known that Du Shi was born in Henei, Henan province.[2] Du Shi became an Officer of Merit in his local commandery before receiving an appointment in 23 as a government clerk under Emperor Gengshi of Han (r. 23–25), following the revolt against the Xin Dynasty usurper Wang Mang (r. 9–23).[2] However, Du soon after swore his allegiance to Emperor Guangwu of Han (r. 25–57), who is considered the true founder of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220).[2]

Censorate officer

Under Emperor Guangwu, Du Shi was appointed as an officer in the Censorate and was in charge of monitoring affairs and upholding law and order within the new capital at Luoyang.[2] When the undisciplined troops of the military officer Xiao Guang (d. 26) ran rampant in the capital city and terrorized its inhabitants without any perceivable action on Xiao's part to prevent it, Du Shi had him arrested.[3] Du had Xiao summarily executed without explicit consent from the throne, sending in a report of the event only after the execution.[3] Guangwu was not displeased with this, as he called him into court to grant him an insignia which justified his actions.[2] Shortly after this event, the bandit leader Yang Yi (d. 26) caused a major disturbance in Hedong Commandery, which Du Shi was sent to quell.[4] When word of the arrival of Du Shi's forces in the region, Yang Yi planned to flee across the Yellow River.[4] However, Du Shi anticipated this, sending a raiding party to burn the boats Yang Yi intended to use for his escape.[4] After conscripting troops from Hedong Commandery, Du Shi led a surprise ambush with a cavalry unit that dispersed Yang's bandits and annihilated them.[2]

Administrator

For three years, Du served as a county magistrate in Henan province where his administration gained wide acclaim from provincial authorities.[5] Afterwards, Du distinguished himself as a Commandant in Pei and in Runan.[6] In 31 he was appointed as an administrator over Nanyang.[6] While serving there, he had an array of dykes and canals built for land reclamation and growth of local agriculture.[6] It is here that he also developed a water-powered reciprocator for bellows in smelting cast iron, a machine which reportedly saved an enormous amount of physical labor.[6] It is recorded that the locals were so fond of him that they often referred to him as "Mother Du" and compared him to noteworthy figures of history, such as Shao Xinchen of the Western Han era.[6]

Du Shi was by all means a local administrator, yet he also made recommendations to the imperial court on policy issues.[6] He recommended that the Tiger Tallies system be reinstated.[6] This was a means for imperial authorities to check possible official corruption in the forgery of mobilization of troops for war.[6] Du also nominated several minor officials he deemed worthy as candidates for higher posts in the capital, including Fu Zhang.[6] In a memorial of 37, he urged the court to consider Fu as the next Imperial Secretary.[6]

Death

Du Shi's reputation was somewhat stymied in 38 when he was accused of having one of his retainers sent to kill a man out of vengeance for his brother.[6] In that same year, Du became ill and died.[6] Despite Du's long-standing official career, the Director of Retainers Bao Yong reported that no proper funeral ceremony could be arranged for Du, since Du was nearly broke when he died.[6] However, the Emperor had an imperial edict made which granted Du a proper funeral ceremony at his commandery residence in the capital, along with silk to pay for the expenditures.[6]

The Water-Powered Blast Furnace

Book of Later Han account

The engineer and statesman Du Shi is mentioned briefly in the Book of Later Han (Hou Han Shu) as follows (in Wade-Giles spelling):

| “ | In the seventh year of the Chien-Wu reign period (31 AD) Tu Shih was posted to be Prefect of Nanyang. He was a generous man and his policies were peaceful; he destroyed evil-doers and established the dignity (of his office). Good at planning, he loved the common people and wished to save their labor. He invented a water-power reciprocator for the casting of (iron) agricultural implements. Those who smelted and cast already had the push-bellows to blow up their charcoal fires, and now they were instructed to use the rushing of the water to operate it...Thus the people got great benefit for little labor. They found the 'water(-powered) bellows' convenient and adopted it widely.[7] | ” |

Donald B. Wagner writes that there is no remaining physical evidence of the bellows which Du Shi used, so modern scholars are still unable to determine whether or not they were made of leather or giant wooden fans as described later in the 14th century.[8]

Spread of Use

The historical text Sanguo Zhi (Records of the Three Kingdoms) records the use of both human labor and horse-power to operate metallurgic bellows of a blast furnace before water-power was applied.[7] It also records that the engineer and Prefect of Luoling Han Ji (d. 238) reinvented a similar water-powered bellows that Du Shi had earlier pioneered.[9] Two decades after this, it is recorded that another design for water-powered bellows was created by Du Yu (222–285).[7] In the 5th-century text of the Wu Chang Ji, its author Pi Ling wrote that a planned, artificial lake had been constructed in the Yuanjia reign period (424–429) for the sole purpose of powering water wheels aiding the smelting and casting processes of the Chinese iron industry.[10] The 5th-century text Shui Jing Zhu mentions the use of rushing river water to power waterwheels, as does the Tang Dynasty (618–907) geography text of the Yuanhe Jun Xian Tu Chi, written in 814 AD.[9][11]

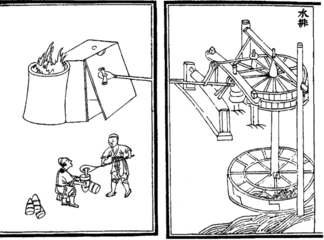

Although Du Shi is the first historical figure to apply water power to metallurgic bellows, the oldest extant Chinese illustration depicting such a device in operation can be seen in a picture of the Nong Shu, printed by 1313 AD during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) of China.[12] The text was written by Wang Zhen, who explained the methods used for a water-powered blast-furnace (Wade-Giles spelling):

| “ | According to modern study (+1313!), leather bag bellows were used in olden times, but now they always use wooden fan (bellows)(mu shan). The design is as follows. A place beside a rushing torrent is selected, and a vertical shaft is set up in a framework with two horizontal wheels so that the lower one is rotated by the force of the water. The upper one is connected by a driving belt to a (smaller) wheel in front of it, which bears an eccentric lug (lit. oscillating rod). Then all as one, following the turning (of the driving wheel), the connecting-rod attached to the eccentric lug pushes and pulls the rocking roller, the levers to left and right of which assure the transmission of the motion to the piston-rod (chih mu). Thus this is pushed back and forth, operating the furnace bellows far more quickly than would be possible with man-power.[13] | ” |

See also

- Trip hammer

- List of Chinese people

- Antipater of Thessalonica

Notes

- ↑ Book of Later Han, vol. 31

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Crespigny, 183.

- 1 2 Crespigny, 183 & 890.

- 1 2 3 Crespigny, 183 & 963

- ↑ Crespigny, 183–184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Crespigny, 184.

- 1 2 3 Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 370

- ↑ Wagner, 77.

- 1 2 Wagner, 77–78.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 371-371.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 373.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 371.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 376.

References

- de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23-220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 90-04-15605-4.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Wagner, Donald B. (2001). The State and the Iron Industry in Han China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Publishing. ISBN 87-87062-83-6.