Domestic violence in the United States

.jpg)

Domestic violence in United States is a form of violence expressed by one partner or partners against another partner or partners in the context of an intimate relationship in the U.S.. It is recognized as an important social problem by governmental and non-governmental agencies, and various Violence Against Women Acts have been passed by the US Congress in an attempt to stem this tide.

Victimization from domestic violence transcends the boundaries of gender and sexual orientation, with significant percentages of LGBT couples facing these issues.[1] Men are subject to domestic violence in large numbers, such as in situational couple violence as mentioned above, but they are less likely to be physically hurt than female victims.[2][3] Social and economically disadvantaged groups in the U.S. regularly face worse rates of domestic violence than other groups. For example, about 60% of Native American women are physically assaulted in their lifetime by a partner or spouse.[4]

Many scholarly studies of the problem have stated that is often part of a dynamic of control and oppression in relationships, regularly involving multiple forms of physical and non-physical abuse taking place concurrently. Intimate terrorism, an ongoing, complicated use of control, power and abuse in which one person tries to assert systematic control over another psychologically. shelters exist in many states as well as special hotlines for people to call for immediate assistance, with non-profit agencies trying to fight the stigma that people both face in reporting these issues.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary definition, domestic violence is: "the inflicting of physical injury by one family or household member on another; also: a repeated or habitual pattern of such behavior."[5]

Governmental definitions

The following definition applies for the purposes of subchapter III of chapter 136 of title 42 of the US Code:

The term 'domestic violence' includes felony or misdemeanor crimes of violence committed by a current or former spouse of the victim, by a person with whom the victim shares a child in common, by a person who is cohabitating with or has cohabitated with the victim as a spouse, by a person similarly situated to a spouse of the victim under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction receiving grant monies, or by any other person against an adult or youth victim who is protected from that person’s acts under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction.[6]

It was inserted into the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 by section 3(a) of the Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005.[7]

It also applies for the purposes of section 7275 of subpart 17 of Part D of subchapter V of chapter 70 of title 20,[8] section 1437F of subchapter I of chapter 8 of title 42,[9] and subchapter XII-H of chapter 46 of title 42 of the US Code.[10]

The US Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) defines domestic violence as a "pattern of abusive behavior in any relationship that is used by one partner to gain or maintain power and control over another intimate partner". The definition adds that domestic violence "can happen to anyone regardless of race, age, sexual orientation, religion, or gender", and can take many forms, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional, economic, and psychological abuse.[11]

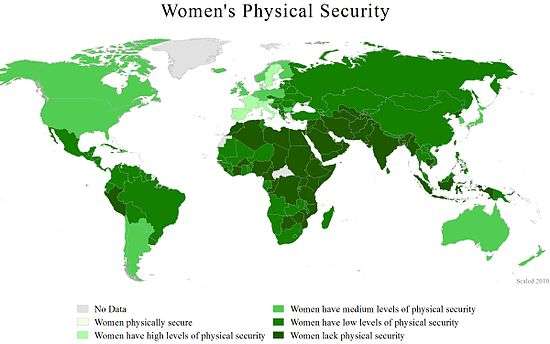

A global problem

Kofi Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations, declared in a 2006 report posted on the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) website that:

Violence against women and girls is a problem of pandemic proportions. At least one out of every three women around the world has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime with the abuser usually someone known to her.[12]

-

A world map showing countries by women's physical security, 2011.

Forms

Domestic violence may include verbal, emotional, economic, physical and sexual abuse. All forms of domestic abuse have one purpose: to gain and maintain control over the victim. Abusers use many tactics to exert power over their spouse or partner: dominance, humiliation, isolation, threats, intimidation, denial and blame.[13]

The dynamics between the couple may include

- Situational couple violence, which arises out of conflicts that escalate to arguments and then to violence, is not connected to a general pattern of control, generally infrequent, and likely the most common type of intimate partner violence. Women are as likely as men to be abusers, however, women are somewhat more likely to be physically injured, but are also more likely to successfully find police intervention.[14]:3

- Intimate terrorism (IT), involves a pattern of ongoing control using emotional, physical and other forms of domestic violence and is what generally leads victims. It is what was traditionally the definition of domestic violence and is generally illustrated with the "Power and Control Wheel"[15] to illustrate the different and inter-related forms of abuse.[14]:2–4

- Violent resistance (VR), or "self-defense", is violence perpetrated by victims against their abusive partners.[16]

- Common couple violence, where both partners are engaged in domestic violence actions.[17]

- Mutual violent control (MVC) is a rare type of intimate partner violence that occurs when both partners act in a violent manner, battling for control.[18]

Incidence

The ten states with the highest rate of females murdered by males were, as of 2010, Nevada, South Carolina, Tennessee, Louisiana, Virginia, Texas, New Mexico, Hawaii, Arizona, Georgia.[19] In 2009, for homicides in which the victim to offender relationship could be identified, 93% of female victims were murdered by a male they knew, 63% of them in the context of an intimate relationship.[20]

Several studies in the U.S. have found that domestic violence is significantly more common in the families of police officers than in other families, which is very problematic, since police officers must play a key role in responding to incidents of DV.[21][22][23]

Gender aspects of abuse

In the United States, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics in 1995 women reported a six times greater rate of intimate partner violence than men, suggesting either higher levels of violence by men, higher levels of reporting by women, or disproportionate response by law enforcement.[24][25] The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) indicates that in 1998 about 876,340 violent crimes were committed in the U.S. against women by their current or former spouses, or boyfriends.[26] According to the Centers for Disease Control, in the United States 4.8 million women suffer intimate partner related physical assaults and rapes and 2.9 million men are victims of physical assault from their partners.[27]

A large study, compiled by Martin S. Fiebert, shows that women are as likely to be abusive to men, but that men are less likely to be hurt. However, he noted, men are seriously injured in 38 percent of the cases in which "extreme aggression" is used. Fiebert additionally noted that his work was not meant to minimize the serious effects of men who abuse women.[24][28][nb 1] Women are far more likely to use weapons, such as sharp or blunt objects other than a knife or firearm.[29]

Studies have found that men are much less likely to report victimization in these situations.[30] According to some studies, less than 1% of domestic violence cases are reported to the police.[31][32] In the United States 10–35% of the population will be physically aggressive towards a partner at some point in their lives.[24][33][34] As abuse becomes more severe women become increasingly overrepresented as victims.[33]

The National Violence Against Women Survey for 2000 reported that 25% of women and 7.6% of men reported being victims of intimate partner violence at some point in their lives.[35] The rate of intimate partner violence in the U. S. has declined since 1993.[36]

As pointed out by a 2006 Amnesty International report, The Maze of Injustice: The Failure to Protect Indigenous Women From Sexual Violence in the USA[37] the data for Native women reveals high levels of sexual violence. Statistics gathered by the U.S. government reveal that Native American and Alaska Native women are more than 2.5 times more likely to be sexual assaulted than women in the United States in general;[38] more than one in three Native women will be raped in their lifetime.[39]

Straus and Gelles found that in couples reporting spousal violence, 27 percent of the time the man struck the first blow; in 24 percent of cases, the woman initiated the violence. The rest of the time, the violence was mutual, with both partners brawling. The results were the same even when the most severe episodes of violence were analyzed. In order to counteract claims that the reporting data was skewed, female-only surveys were conducted, asking females to self-report, and the data was the same.[40] The simple tally of physical acts is typically found to be similar in those studies that examine both directions, but some studies show that male violence may be more serious. Male violence may do more damage than female violence;[41] women are more likely to be injured and/or hospitalized. Women are more likely to be killed by an intimate than the reverse (according to the Department of Justice, the rate is 63.7% to 36.3%),[42] and women in general are more likely to be killed by their spouses than by all other types of assailants combined.[43]

A research article published in the Journal of Family Psychology, "Estimating the Number of American Children Living in Partner-Violent Families", says that contrary to media and public opinion women commit more acts of violence than men in eleven categories: throw something, push, grab, shove, slap, kick, bite, hit or threaten a partner with a knife or gun. The study, which was based on interviews with 1,615 married or cohabiting couples and extrapolated nationally using census data, found that 21 percent of couples reported domestic violence.[44] However, one of the report's authors, Renee McDonald, who was interviewed by The Washington Times cautioned, "We don't want to minimize [female-to-male violence], but on the other hand we don't want to forget the fact that men can be much more harmful to women."[45]

The National Institute of Justice contends that national surveys supported by NIJ, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics that examine more serious assaults do not support the conclusion of similar rates of male and female spousal assaults. These surveys are conducted within a safety or crime context and clearly find more partner abuse by men against women.[46][nb 2]

Statistics

Over a year

- 1% of all women (age > 18) who participated in a UN national study in 1995–96, who may or may not have been married or partnered, were victims of domestic abuse within the previous 12-month period. Since this population included women who had never been partnered, the prevalence of domestic violence may have been greater.[47]

- A report by the United States Department of Justice in 2000 found that 1.3% of women and 0.9% of men reported experiencing domestic violence in the past year.[2]

- About 2.3 million people are raped or physically assaulted each year by a current or former intimate partner or spouse.[48]

- Physically assaulted women receive an average of 6.9 physical assaults by the same partner per year.[48]

During pregnancy

The United States was one of the countries identified by a United Nations study with a high rate of domestic violence resulting in death during pregnancy.[49][nb 3]

During one's lifetime

- According to The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and The National Institute of Justice, nearly 25% of women experience at least one physical assault during adulthood by a partner.[48]

- 22% of the women had been subject to domestic violence during some period of their life, according to a United Nations study. Since this population included women who had never been married or partnered, the prevalence of domestic violence may have been greater.[47]

- According to a report by the United States Department of Justice in 2000, a survey of 16,000 Americans showed 22.1 percent of women and 7.4 percent of men reported being physically assaulted by a current or former spouse, cohabiting partner, boyfriend or girlfriend, or date in their lifetime.[2]

- 60% of American Indian and Alaska Native women will be physically assaulted in their lifetime.[48]

- A 2013 report by the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 26% of male homosexuals and 44% of lesbians surveyed reported experiencing intimate partner violence. The study evaluated 2010 data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, which involved over 16,000 U.S. adults.[1]

Injury

In 1992, domestic violence was the leading cause of injury for women between 15 and 44; more than rapes, muggings, and car accidents combined.[50] The levels of domestic injury against men have not been investigated to the same extent.

Rape

- 1 in 33 men and 1 in 7 women have experienced an attempted or completed rape committed by a partner. More than one in three American Indian and Alaska Native women will be raped in their lifetimes.[48][51]

- A 2013 CDC study stated that 28% of straight women who had been raped experienced their first rape as a child, with the crime taking place between the ages of 11 and 17.[1]

Murder

Women are more likely than men to be murdered by an intimate partner. Of those killed by an intimate partner, about three quarters are female and about a quarter are male. In 1999 in the United States, 1,218 women and 424 men were killed by an intimate partner,[52] and 1,181 females and 329 males were killed by their intimate partners in 2005.[53][54] In 2007, 2,340 deaths were caused by intimate partner violence—making up 14% of all homicides. 70% of these deaths were females and 30% were males.[55]

Dating violence

Dating violence is often a precursor to domestic violence. 22% of high school girls and 32% of college women experienced dating violence in a 2000 study. 20.6% of women experienced two or more types of dating violence and 8.3% of women experienced rape, stalking or physical aggression while dating.[56] The levels of dating violence against men has not been investigated to the same extent.

Stalking

According to the Centers for Disease Control National Intimate Partner Violence Survey results of 2010, 1 in 6 women (15.2%) have been stalked during their lifetime, compared to 1 in 19 men (5.7%).[57] Additionally, 1 in 3 bisexual women (37%) and 1 in 6 heterosexual women (16%) have experienced stalking victimization in their lifetime during which they felt very fearful or believed that they or someone close to them would be harmed or killed.[58]

Socio-economic impacts

While domestic violence crosses all socio-economic classes, Intimate Terrorism (IT) is more prevalent among poor people. When evaluating situational couple violence, poor people, subject to greater strains, have the highest percentage of situational couple violence, which does not necessarily involve serious violence.[14]:4

Regarding ethnicity, socio-economic standing and other factors often have more to do with rates of domestic violence. When comparing the African American population to European Americans by socio-economic class, the rates of domestic violence are roughly the same. Since there are more poor African Americans, though, there is a higher incidence of domestic violence overall. It is not possible to evaluate the rate of domestic violence by ethnicity alone, because of the variability of cultural, economic and historical influences and the forms of domestic violence (situational couple violence, intimate terrorism) affecting each population of people.[14]:4

Effects on children

Up to 10 to 20% children in the United States witness abuse of a parent or caregiver annually. As a result, they are more likely to experience neglect or abuse, less likely to succeed at school, have poor problem-solving skills, subject to higher incidence of emotional and behavioral problems, and more likely to tolerate violence in their adult relationships.[59] Complicating this already bleak picture, parental psychopathology in the wake of domestic violence can further compromise the quality of parenting, and in turn increase the risk for the child's developing emotional and behavioral difficulties if mental health care is not sought.[60]

Homelessness

According to the authors of "Housing Problems and Domestic Violence," 38% of domestic violence victims will become homeless in their lifetime.[48] Domestic violence is the direct cause of homelessness for over half of all homeless women in the United States.[61] According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, domestic violence is the third leading cause of homelessness among families.[62]

Economic impacts

Economic abuse can occur across all socio-economic levels.[63]

The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence in the United States reports that:

- 25% - 50% of victims of abuse from a partner have lost their job due to domestic violence.

- 35% - 56% of victims of domestic violence are harassed at work by their partners.

- More than 1.75 million workdays are lost each year to domestic violence. Lost productivity due to missed workdays and decreased productivity, with increased health and safety costs, results in a loss of $3 to $5 billion each year.[64]

The Centers for Disease Control has released that the medical care, mental health services, and lost productivity cost of intimate partner violence was an estimated $8.3 billion in 2003 dollars for women alone.[65]

Religion

One 2004 study by William Bradford Wilcox examined the relationship between religious affiliation, church attendance, and domestic violence, using data on wives' reports of spousal violence from three national United States surveys conducted between 1992 and 1994.[66] The study found that the lowest reported rates of domestic violence occurred among active conservative Protestants (2.8% of husbands committed domestic violence), followed by those who were religiously unaffiliated (3.2%), nominal mainline Protestants (3.9%), active mainline Protestants (5.4%), and nominal conservative Protestants (7.2%).[66]

Overall (including both nominal and active members), the rates among conservative Protestants and mainline Protestants were 4.8% and 4.3%, respectively.[66] Examining Wilcox's study, Van Leewen finds that the parenting style of conservative Protestant fathers is characterized by features which have been linked to positive outcomes among children and adolescents,[nb 4][67] that there is no evidence that gender-traditionalist ideology of the "soft patriarchal" kind is a strong predictor of domestic physical abuse,[nb 5][67] and that "gender hierarchicalist males" who are frequent and active church members function positively in the domestic environment. [nb 6][67]

Another 2007 study by Christopher G. Ellison found that "religious involvement, specifically church attendance, protects against domestic violence, and this protective effect is stronger for African American men and women and for Hispanic men, groups that, for a variety of reasons, experience elevated risk for this type of violence."[68]

History

Prior to the mid-1800s most legal systems implicitly accepted wife beating as a valid exercise of a husband's authority over his wife.[69][70] One exception, however, was the 1641 Body of Liberties of the Massachusetts Bay colonists, which declared that a married woman should be "free from bodilie correction or stripes by her husband."[71]

Political agitation during the 19th century led to changes in both popular opinion and legislation regarding domestic violence within the United Kingdom and the United States.[72][73] In 1850, Tennessee became the first state in the United States to explicitly outlaw wife beating.[74][75] Other states soon followed suit.[70][76]

In 1878, the Matrimonial Causes Act made it possible for women in the UK to seek separations from abusive husbands.[77] By the end of the 1870s, most courts in the United States were uniformly opposed to the right of husbands to physically discipline their wives.[78] By the early 20th century, it was common for the police to intervene in cases of domestic violence in the United States, but arrests remained rare.[79] Wife beating was made illegal in all states of the United States by 1920.[80][81]

Modern attention to domestic violence began in the women's movement of the 1970s, particularly within feminism and women's rights, as concern about wives being beaten by their husbands gained attention. The first known use of the expression "domestic violence" in a modern context, meaning "spouse abuse, violence in the home" was in 1973.[82][83] With the rise of the men's movement of the 1990s, the problem of domestic violence against men has also gained significant attention.

Attention to violence against men began in the late 1980s. Broadly speaking, such claims have been discounted by feminist organizations, claiming they are an attempt to downplay violence against women.

Laws

Victims of DV are offered legal remedies, which include the criminal law, as well as obtaining a protection order. The remedies offered can be both of a civil nature (civil orders of protection and other protective services) and of a criminal nature (charging the perpetrator with a criminal offense). People perpetrating DV are subject to criminal prosecution, most often under assault and battery laws. Other common statutes used include, but are not reduced to, harassment, menacing, false imprisonment. Perpetrators of DV can be charged under general statutes, but some states have enacted specific statutes dealing only with DV. Under South Carolina code, the crime of "Criminal domestic violence" states that "it is unlawful to: (1) cause physical harm or injury to a person's own household member; or (2) offer or attempt to cause physical harm or injury to a person's own household member with apparent present ability under circumstances reasonably creating fear of imminent peril." If aggravated circumstances are present, people can be charged with the crime of "Criminal domestic violence of a high and aggravated nature." Criminal domestic violence is not the only charge possible in South Carolina, people can also be charged under other general statutes.[84][85][86]

Violence Against Women Acts

Three Violence Against Women Acts (VAWA) (1994, 2000, 2005) United States federal laws have been signed into law by the President to end domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking. The law helped victim advocates and government agencies to work together, created prevention and victim support programs, and resulted in new punishments for certain violent crimes, which by 2005 resulted in:

- 49.8% reduction of non-fatal, violent victimizations committed by intimate partners.

- In the first six years, an estimated $14.8 billion in net averted social costs.

- 51% increase in reporting of domestic violence and 18% increase in National Domestic Violence Hotline calls each year, evidence that as victims become aware of remedies, they break the code of silence.[48][87]

Family Violence Prevention and Services Act

The Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) provides federal funding to help victims of domestic violence and their dependent children by providing shelter and related help, offering violence prevention programs, and improving how service agencies work together in communities.

- Formula Grants. This money helps states, territories, and tribes create and support programs that work to help victims and prevent family violence. The amount of money is determined by a formula based partly on population. The states, territories, and tribes distribute the money to thousands of domestic violence shelters and programs.

- The 24-hour, confidential, toll-free National Domestic Violence Hotline provides support, information, referrals, safety planning, and crisis intervention in more than 170 languages to hundreds of thousands of domestic violence victims each year.

- The Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances (DELTA) Program teaches people ways to prevent violence.[87]

Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances (DELTA)

The DELTA program, funded by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), works towards preventing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in certain funded communities. The way that the DELTA program works towards prevention is by understanding factors that influence violence and then focusing on how to prevent these factors. This is done by using a social ecological model which illustrates the connection between Individual, Relationship, Community, and Societal factors that influence violence.

Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban

The Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban is a United States federal law enacted in 1996 to ban firearms and ammunitions to individuals convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence, or who are under a restraining (protection) order for domestic abuse in all 50 states.[88][89]

United States federal probation and supervised release for domestic violence offenders

The United States federal probation and supervised release law:

- Requires first-time domestic violence offenders convicted of domestic violence crimes to attend court-approved non-profit offender rehabilitation programs within a 50-mile radius of the individual's legal residence.

- Makes probation mandatory for first-time domestic violence offenders not sentenced to a term of imprisonment.[90]

United States asylum for victims of domestic violence

In 2014 the Board of Immigration Appeals, America's highest immigration court, found for the first time that women who are victims of severe domestic violence in their home countries can be eligible for asylum in the United States.[91] However, this ruling was in the case of a woman from Guatemala and thus applies only to women from Guatemala.[91]

Law enforcement

In the 1970s, it was widely believed that domestic disturbance calls were the most dangerous type for responding officers, who arrive to a highly emotionally charged situation. This belief was based on FBI statistics which turned out to be flawed, in that they grouped all types of disturbances together with domestic disturbances, such as brawls at a bar. Subsequent statistics and analysis have shown this belief to be false.[92][93]

Statistics on incidents of domestic violence, published in the late 1970s, helped raise public awareness of the problem and increase activism.[94][95] A study published in 1976 by the Police Foundation found that the police had intervened at least once in the previous two years in 85% of spouse homicides.[96] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, feminists and battered women's advocacy groups were calling on police to take domestic violence more seriously and change intervention strategies.[97] In some instances, these groups took legal action against police departments, including Los Angeles's, Oakland, California's and New York City's, to get them to make arrests in domestic violence cases.[98] They claimed that police assigned low priority to domestic disturbance calls.[99]

The Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment was a study done in 1981–1982, led by Lawrence W. Sherman, to evaluate the effectiveness of various police responses to domestic violence calls in Minneapolis, Minnesota, including sending the abuser away for eight hours, giving advice and mediation for disputes, and making an arrest. Arrest was found to be the most effective police response. The study found that arrest reduced the rate by half of re-offending against the same victim within the following six months.[100] The results of the study received a great deal of attention from the news media, including The New York Times and prime-time news coverage on television.[101]

Many U.S. police departments responded to the study, adopting a mandatory arrest policy for spousal violence cases with probable cause.[102] By 2005, 23 states and the District of Columbia had enacted mandatory arrest for domestic assault, without warrant, given that the officer has probable cause and regardless of whether or not the officer witnessed the crime.[103] The Minneapolis study also influenced policy in other countries, including New Zealand, which adopted a pro-arrest policy for domestic violence cases.[104]

However, the study was subject of much criticism, with concerns about its methodology, as well as its conclusions.[101] The Minneapolis study was replicated in several other cities, beginning in 1986, with some of these studies having different results; one of which being the fact that the deterrent effect observed in the Minneapolis experiment was largely localized.[105] In the replication studies which were far more broad and methodologically sound in both size and scope, arrest seemed to help in the short run in certain cases, but those arrested experienced double the rate of violence over the course of one year.[105]

Each agency and jurisdiction within the United States has its own Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) when it comes to responding and handling domestic calls. Generally, it has been accepted that if the understood victim has visible (and recent) marks of abuse, the suspect is arrested and charged with the appropriate crime. However, that is a guideline and not a rule. Like any other call, domestic abuse lies in a gray area. Law enforcement officers have several things to consider when making a warrantless arrest:

- Are there signs of physical abuse?

- Were there witnesses?

- Is it recent?

- Was the victim assaulted by the alleged suspect?

- Who is the primary aggressor?

- Could the victim be lying?

- Could the suspect be lying?

Along with protecting the victim, law enforcement officers have to ensure that the alleged abusers' rights are not violated. Many times in cases of mutual combatants, it is departmental policy that both parties be arrested and the court system can establish truth at a later date. In some areas of the nation, this mutual combatant philosophy is being replaced by the primary abuser philosophy in which case if both parties have physical injuries, the law enforcement officer determines who the primary aggressor is and only arrests that one. This philosophy started gaining momentum when different government/private agencies started researching the effects. It was found that when both parties are arrested, it had an adverse effect on the victim. The victims were less likely to call or trust law enforcement during the next incident of domestic abuse.[106]

State due diligence

International law requires that States exercise due diligence to reduce domestic violence and, when violations occur, to provide effective investigation and redress to victims.[107] In 2011, Rashida Manjoo, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, urged the United States to "[e]xplore more uniform remedies for victims of domestic violence," "[r]e-evaluate existing mechanisms at federal, state, local, and tribal levels for protecting victims and punishing offenders," "[e]stablish meaningful standards for enforcement of protection orders," and "[i]nitiate more public education campaigns."[108] After the Supreme Court of the United States held in Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales that Jessica Lenahan, a victim of domestic violence, had no constitutional right to the enforcement of her restraining order, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights found that the United States "failed to act with due diligence" to protect Jessica Lenahan and her daughters Leslie, Katheryn, and Rebecca Gonzales from domestic violence, "which violated the state’s obligation not to discriminate and to provide for equal protection before the law."[109] The Commission further held that "the failure of the United States to adequately organize its state structure to protect [Leslie, Katheryn, and Rebecca] from domestic violence was discriminatory and constituted a violation of their right to life."[109]

Freedom from domestic violence resolution movement

Since 2011,[110] twenty-six local governments in the United States have passed resolutions declaring freedom from domestic violence to be a fundamental human right,[111] rooted in the recognition of governmental responsibility to ensure this right.[112] These resolutions were passed by Albany Common Council (NY), Albany County Legislature (NY), Austin City Council (TX), Boston City Council (MA), Cayuga Heights Town Board (NY), City Council of Baltimore (MD), City Council of Chicago (IL), City Council of Jacksonville (FL), City Council of the City of Miami Springs (FL), Council of the City of Cincinnati (OH), Council of Washington, D.C., Erie County Legislature (NY), Ithaca Common Council (NY), Ithaca Town Board (NY), Lansing Town Board (NY), Laredo with Webb County (TX), Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners (FL), Montgomery City with Montgomery County (AL), Pratville (AL), Seattle Human Rights Commission (WA), State College (PA), Tompkins County Council of Governments (NY), Tompkins County Legislature (NY), Travis County Commissioners Court (TX) and Village of Cayuga Heights (NY).[113]

Although the resolutions are not identical, most declare that freedom from domestic violence is a fundamental human right, and further resolve that the state and local governments should secure this human right on behalf of their citizens and should incorporate the resolution's principles into their policies and practices.[114]

Support organizations

Christian

A contributing factor to the disparity of responses to abuse is lack of training. Many Christian seminaries had not educated future church leaders about how to manage violence against women. Once pastors began receiving training, and announced their participation in domestic violence educational programs, they immediately began receiving visits from women church members who had been subject to violence.[115]

The first Theological Education and Domestic Violence Conference, sponsored by the Center for the Prevention of Sexual and Domestic Violence, was held in 1985 to identify topics that should be covered in seminaries. When church leaders first encounter sexual and domestic violence, they need to know what community resources are available. They need to focus on ending the violence, rather than on keeping families together.[115]

One of the Salvation Army's missions is working with victims of domestic abuse. They offer safe housing, therapy, and support.

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence

The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, otherwise known as the NCADV, is a non-profit organization centered on creating a culture where domestic violence is not tolerated. The NCADV works toward this vision by promoting a society that empowers the victims and survivors of domestic violence and holds their abusers accountable. They work toward their goal of changing society to have a zero tolerance for domestic violence by effecting public policy, increasing understanding of the impact of domestic violence, and providing education and programs for victims.[116]

The NCADV works with national organisations to push for policies and legislation that work to protect victims and survivors of domestic violence. They also offer programs for victims to assist them in rehabilitation such as The Cosmetic and Reconstructive Surgery Program. This program is offered to survivors and consists of plastic surgeons volunteering their services to assist survivors of domestic violence, who cannot afford plastic surgery, in removing their scars left by an abusive partner.[116]

Domestic violence shelters

Domestic violence shelters are buildings, usually sets of apartments, that are set as a place where victims of domestic violence can seek refuge from their abusers. In order to keep the abuser from finding the victim, the location of these shelters are kept confidential. These shelters provide the victims with the basic living necessities including food. Some domestic violence shelters have room for victimized mothers to bring their children, therefore offering childcare as well. Although the length of time a person can stay in these shelters is limited, most shelters help victims in finding a permanent home, job, and other necessities one needs to start a new life. Domestic Violence shelters should also be able to refer its victims to other services such as legal help, counseling, support groups, employment programs, health services, and financial opportunities.[117]

Hotlines

- The National Domestic Violence Hotline is a 24-hour, confidential, toll-free hotline created through the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act. Hotline staff immediately connect the caller to a service provider in his or her area. Highly trained advocates provide support, information, referrals, safety planning, and crisis intervention in 170 languages to hundreds of thousands of domestic violence victims.[118]

- Loveisrespect, National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline, launched February 8, 2007 by the National Domestic Violence Hotline, is a 24-hour national Web-based and telephone resource, created to help teens (ages 13–18) experiencing dating abuse, and is the only helpline in the country serving all 50 states, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.[119]

Reduction programs

Community activism by men

Men's groups against domestic violence and forced rape, found around the world, take measures to reduce their use of violence. Typical activities include group discussions, education campaigns and rallies, work with violent men, and workshops in schools, prisons and workplaces. Actions are frequently conducted in collaboration with women's organizations that are involved in preventing violence against women and providing services to abused women. In the United States alone, there are over 100 such men's groups, many of which focus specifically on sexual violence.[120]

Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (Duluth Model)

The Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (Duluth Model), featured in the documentary Power and Control: Domestic Violence in America,[121][122] was the first multi-disciplinary program designed to coordinate the actions of a variety of agencies in Duluth, Minnesota dealing with domestic violence for a more effective outcome and has become a model for programs in other jurisdictions.[123] A nationwide study published in 2002 sponsored by the federal government found that batterers who complete programs based on the "Duluth Model," are less likely to repeat acts of domestic violence than those who do not complete any batterers' intervention program.[124]

See also

Legal remedies:

- Address confidentiality program, some states in the United States

- Injunction

- Restraining order

Organizations:

- AHA Foundation (Muslim women's rights in western countries)

- Futures Without Violence

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence

- National Network to End Domestic Violence

- Peaceful Families Project (Muslim organization)

- Stop Abuse For Everyone, inclusive of all types of domestic violence victims: age, LBGT, gender, etc.

- Tahirih Justice Center

- Convicted Women Against Abuse

General:

References

- Notes

- ↑ Martin S. Fiebert of the Department of Psychology at California State University, Long Beach, has compiled an annotated bibliography of research relating to spousal abuse by women on men. This bibliography examines 275 scholarly investigations: 214 empirical studies and 61 reviews and/or analyses appear to demonstrate that women are as physically aggressive, or more aggressive, than men in their relationships with their spouses or male partners. The aggregate sample size in the reviewed studies exceeds 365,000.[24] In a Los Angeles Times article about male victims of domestic violence, Fiebert suggests that "...consensus in the field is that women are as likely as men to strike their partner but that—as expected—women are more likely to be injured than men."[28]

- ↑ The National Institute of Justice states that studies finding equal or greater frequency of abuse by women against men are based on data compiled through the Conflict Tactics Scale. This survey tool was developed in the 1970s and may not be appropriate for intimate partner violence research because it does not measure control, coercion, or the motives for conflict tactics; it also leaves out sexual assault and violence by ex-spouses or partners and does not determine who initiated the violence.[46]

- ↑ India and Bangladesh were also noted as countries with a high prevalence of death during pregnancy due to domestic abuse.[49]

- ↑ "He concludes that conservative Protestant fathers’ neotraditional parenting style seems to be closer to the authoritative style—characterized by moderately high levels of parental control and high levels of parental supportiveness—that has been linked to positive outcomes among children and adolescents."

- ↑ ‘The upshot is that we have no evidence so far that a gender-traditionalist ideology—at least of the soft patriarchal variety—is a strong predictor of domestic physical abuse.’

- ↑ "Gender hierarchicalist males—at least those who have frequent and active church involvement—turn out, on average, to be better men than their theories: more often than not, they are functional egalitarians, and the rhetoric of male headship may actually be functioning as a covert plea for greater male responsibility and nurturant involvement on the home front."

- Citations

- 1 2 3 Heavey, Susan (January 25, 2013). "Data shows domestic violence, rape an issue for gays". Reuters. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Tjaden, Patricia; Thoennes, Nancy (November 2000). "Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women". National Institute of Justice, United States Department of Justice.

- ↑ Rogers, Kenneth; Baumgardner, Barbara; Connors, Kathleen; Martens, Patricia; Kiser, Laurel (2010), "Prevention of family violence", in Compton, Michael T., Clinical manual of prevention in mental health (1st ed.), Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, p. 245, ISBN 9781585623471,

Women are more often the victims of domestic violence than men and are more likely to suffer injuries and health consequences...

- ↑ Malcoe, LH; Duran, BM; Montgomery, JM (2004). "Socioeconomic disparities in intimate partner violence against Native American women: a cross-sectional study". BMC Med. 2: 20. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-2-20. PMC 446227

. PMID 15157273.

. PMID 15157273. - ↑ Domestic Violence. Merriam Webster. Retrieved 14 Nov. 2011.

- ↑ US Code. Title 42. Chapter 136. Subchapter III. Section 13925(a)(6)

- ↑ The Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005

- ↑ US Code. Title 20. Chapter 70. Subchapter V. Part D. Subpart 17. Section 7275(a)(1).

- ↑ US Code. Title 42. Chapter 8. Subchapter I. violence&url=/uscode/html/uscode42/usc_sec_42_00001437---f000-.html Section 1437F(f)(8)

- ↑ US Code. Title 42. Chapter 46. Subchapter XII-H. Section 3796gg–2.

- ↑ "About Domestic Violence". Office on Violence Against Women. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- ↑ Moradian, Azad. Domestic Violence against Single and Married Women in Iranian Society. Tolerancy International. September 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ↑ Smith, Melinda, M.A.; Segal, Jeanne, Ph.D. (December 2014). "Domestic Violence and Abuse: Signs of Abuse and Abusive Relationships". http://www.helpguide.org. Helpguide.org. Retrieved 14 February 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Ooms, Theodora (2006). A sociologist's perspective on domestic violence: a conversation with Michael Johnson, PhD (pdf). Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP).

- ↑ Power and Control Wheel, National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ Bachman, Ronet; Carmody, Dianne Cyr (December 1994). "Fighting fire with fire: the effects of victim resistance in intimate versus stranger perpetrated assaults against females". Journal of Family Violence. Springer. 9 (4): 317–331. doi:10.1007/BF01531942.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael P.; Ferraro, Kathleen J. (November 2000). "Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: making distinctions". Journal of Marriage and Family. Wiley for the National Council on Family Relations. 62 (4): 948–963. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00948.x. JSTOR 1566718.

- ↑ Saunders, Daniel G. (1988), "Wife abuse, husband abuse, or mutual combat? A feminist perspective on the empirical findings", in Yllö, Kersti; Bograd, Michele Louise, Feminist perspectives on wife abuse, Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications, pp. 90–113, ISBN 9780803930537.

- ↑ http://www.vpc.org/studies/wmmw2012.pdf

- ↑ http://www.vpc.org/studies/wmmw2011.pdf

- ↑ Fagan, Kevin (2012-01-15). "Police domestic violence nearly twice average rate". SFGate. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ "Domestic Violence in Police Families". Purpleberets.org. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ "National Center For Women and Policing". Womenandpolicing.com. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- 1 2 3 4 Fiebert, Martin S. (June 2012). "References examining assaults by women on their spouses or male partners: an annotated bibliography". csulb.edu. California State University, Long Beach. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

This bibliography examines 282 scholarly investigations: 218 empirical studies and 64 reviews and/or analyses, which demonstrate that women are as physically aggressive, or more aggressive, than men in their relationships with their spouses or male partners. The aggregate sample size in the reviewed studies exceeds 369,800.

- ↑ Bachman, Ronet; Saltzman, Linda E. (August 1995). "Violence against women: estimates from the redesigned survey". Bureau of Justice Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice. NCJ 154348 Pdf.

- ↑ Maleque, Saqi S.; Brennan, Virginia. "Domestic violence". meharry.org. Meharry Medical College. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012.

- ↑ CDC (2012). Understanding intimate partner violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. p. 1. Retrieved 7 September 2011. Pdf.

- 1 2 Parsons, Dana (10 April 2002). "Pitcher's case throws a curve at common beliefs about abuse". Los Angeles Times. Orange County: Tribune Publishing.

- ↑ Greenfield, Lawrence A.; et al. (March 1998). "Violence by intimates: analysis of data on crimes by current or former spouses, boyfriends, and girlfriends". Bureau of Justice Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice. NCJ 167237 Pdf.

- ↑ Hamel, John (2007), "Domestic violence: a gender-inclusive conception", in Hamel, John; Nicholls, Tonia L., Family interventions in domestic violence: a handbook of gender-inclusive theory and treatment, New York: Springer Publishing, pp. 5–6, ISBN 9780826103291. Preview.

- ↑ Dziegielewski, Sophia F.; Swartz, Marcia (2007), "Social work's role with domestic violence: women and the criminal justice system", in Roberts, Albert R.; Springer, David W., Social work in juvenile and criminal justice settings (3rd ed.), Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas, p. 270, ISBN 9780398076764. Preview.

- ↑ Sigler, Robert T. (1989). Domestic violence in context: an assessment of community attitudes. Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780669209365.

- 1 2 Straus, Murray A. (1999), "The controversy over domestic violence by women: a methodological, theoretical, and sociology of science analysis", in Arriaga, Ximena B.; Oskamp, Stuart, Violence in intimate relationships, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, pp. 17–44, ISBN 9780761916437.

- ↑ Archer, John (September 2000). "Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. American Psychological Association via PsycNET. 126 (5): 651–680. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. PMID 10989615.

Meta-analyses of sex differences in physical aggression to heterosexual partners and in its physical consequences are reported. Women were slightly more likely (d = –.05) than men to use one or more acts of physical aggression and to use such acts more frequently. Men were more likely (d = .15) to inflict an injury, and overall, 62% of those injured by a partner were women.

Pdf.- Frieze, Irene (September 2000). "Violence in close relationships—development of a research area: Comment on Archer". Psychological Bulletin. American Psychological Association via PsycNET. 126 (5): 681–684. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.681. PMID 10989616.

Assumptions of and conclusions made by feminist researchers about the problems of battered wives are reviewed. It is argued that their focus on marital violence as a form of aggression against women by men and their concern for severely beaten wives may have caused them to ignore high levels of female violence in marriage and dating. J. Archer's meta-analysis of studies of marital and dating violence showed that both sexes display violence in these relationships, although women are more likely to be injured.

- O'Leary, K. Daniel (September 2000). "Are women really more aggressive than men in intimate relationships? Comment on Archer". Psychological Bulletin. American Psychological Association via PsycNET. 126 (5): 685–689. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.685. PMID 10989617.

J. Archer's conclusion that women engage in slightly more physical aggression than men in intimate relationships but sustain more injuries is reasonable in representative samples.

- Frieze, Irene (September 2000). "Violence in close relationships—development of a research area: Comment on Archer". Psychological Bulletin. American Psychological Association via PsycNET. 126 (5): 681–684. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.681. PMID 10989616.

- ↑ WHO. Violence against women and HIV/AIDS: critical intersections: intimate partner violence and HIV/AIDS. The global coalition on women and AIDS. World Health Organization. Retrieved 11 April 2014. Information Bulletin Series, Number 1. Pdf.

- ↑ "Intimate Partner Violence in the U.S.: overview: intimate partner violence has been declining". Bureau of Justice Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Archived from the original on 11 December 2009.

- ↑ AI USA (2007). Maze of injustice: the failure to protect indigenous women from sexual violence in the USA. New York: Amnesty International USA. ISBN 9781887204477. AMR 35/057/2007. English pdf. French pdf. Spanish pdf.

- ↑ Perry, Steven W. (December 2004). "A BJS statistical profile, 1992-2002: American Indians and crime". Bureau of Justice Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Pdf.

- ↑ Tjaden, Patricia; Thoennes, Nancy (November 2000). Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: findings from the national violence against women survey. National Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCJ 183781 Pdf.

- ↑ Straus, Murray A.; Gelles, Richard J. (1990), "How violent are American families? Estimates from the national family violence resurvey and other studies", in Straus, Murray A.; Gelles, Richard J., Physical violence in American families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families, Christine Smith (contributor), New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, p. 105, ISBN 9780887382635.

- ↑ Vivian, Dina; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Jennifer (Summer 1994). "Are bi-directionality violent couples mutually victimized? A gender-sensitive comparison". Violence & Victims. Springer. 9 (2): 107–124. PMID 7696192.

- ↑ Cooper, Alexia; Smith, Erica L. (November 2011), "The sex distribution of homicide victims and offenders differed by type of homicide", in Cooper, Alexia; Smith, Erica L., Homicide trends in the United States, 1980-2008, Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, p. 10. NCJ 236018 Pdf.

- ↑ Browne, Angela; Williams, Kirk R. (1989). "Exploring the effect of resource availability and the likelihood of female-perpetrated homicides". Law and Society Review. Wiley. 23 (1): 75–94. doi:10.2307/3053881. JSTOR 3053881.

- ↑ McDonald, Renee; Jouriles, Ernest N.; Ramisetty-Mikler, Suhasini; Caetano, Raul; Green, Charles E. (March 2006). "Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families". Journal of Family Psychology. American Psychological Association via PsycNET. 20 (1): 137–142. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. Pdf.

- ↑ Staff writer (11 May 2006). "Family violence soars". The Washington Times. News World Media Development. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Measuring intimate partner (domestic) violence". nij.gov. National Institute of Justice. 12 May 2010.

- 1 2 In-depth study on all forms of violence against women. United Nations, General Assembly. 6 July 2006. Page 54. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Violence Against Women Act of 2005, Summary of Provisions. National Network to End Domestic Violence. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- 1 2 In-depth study on all forms of violence against women. United Nations, General Assembly. 6 July 2006. Page 48. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ↑ "Violence Against Women, A Majority Staff Report," Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, 102nd Congress, October 1992, p.3.

- ↑ "Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women." U.S. Department of Justice. November 1998. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ Intimate Partner Violence, 1993-2001

- ↑ "CDC - Injury - Intimate Partner Violence Consequences". Cdc.gov. 2009-12-14. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs, Home of the Duluth Model". Theduluthmodel.org. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "Understanding Intimate Partner Violence" (PDF). cdc.gov. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ In-depth study on all forms of violence against women. United Nations, General Assembly. 6 July 2006. Page 42. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ↑ "National Data on Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, and Stalking" (PDF). cdc.gov. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "NISVS: An Overview of 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation" (PDF). Center for Disease Control. cdc.gov.

- ↑ Child Welfare Information Gateway (2009). Domestic Violence and the Child Welfare System. Administration for Children & Families, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ↑ Schechter, DS; Willheim, E; McCaw, J; Turner, JB; Myers, MM; Zeanah, CH (2011). "The relationship of violent fathers, posttraumatically stressed mothers, and symptomatic children in a preschool-age inner-city pediatrics clinic sample". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 26 (18): 3699–3719. doi:10.1177/0886260511403747. PMID 22170456.

- ↑ Ringwalt CL, Greene JM, Robertson M, McPheeters M (September 1998). "The prevalence of homelessness among adolescents in the United States". Am J Public Health. 88 (9): 1325–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.88.9.1325. PMC 1509094

. PMID 9736871.

. PMID 9736871. - ↑ "Domestic Violence: Statistics & Facts". Safe Horizon. Safe Horizon. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Economic Abuse" (PDF). National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. The Public Policty Office of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ Economic Abuse. National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ "Understanding Intimate Partner Violence" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. cdc.gov.

- 1 2 3 Wilcox, William Bradford. Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands. University of Chicago Press (2004), p181-82. ISBN 0-226-89709-5.

- 1 2 3 Van Leeuwen, ‘Social Sciences’, in Husbands & Larsen, ‘Women, ministry and the Gospel: Exploring new paradigms’, p. 194 (2007).

- ↑ Ellison, Christopher G. (2007). "Race/Ethnicity, Religious Involvement, and Domestic Violence". Violence Against Women. 13 (11): 1094–1112. doi:10.1177/1077801207308259.

- ↑ "Domestic violence". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

In the early 1800s most legal systems implicitly accepted wife-beating as a husband’s right, part of his entitlement to control over the resources and services of his wife.

- 1 2 Daniels, Cynthia R. (1997). Feminists Negotiate the State: The Politics of Domestic Violence. Lanham: Univ. Press of America. pp. 5–10. ISBN 0-7618-0884-1.

- ↑ The Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) at Hanover Historical Texts Project.

- ↑ "Domestic violence". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

Feminist agitation in the 1800s produced a sea change in public opinion...

- ↑ Gordon, Linda (2002). Heroes of Their Own Lives: The Politics and History of Family Violence. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 253–255. ISBN 0-252-07079-8.

- ↑ Kleinberg, S. J. (1999). Women in the United States, 1830-1945. Rutgers University Press. p. 143. ISBN 0-8135-2729-5.

- ↑ Pleck, Elizabeth (1989). "Criminal Approaches to Family Violence". Family Violence. 11.

- ↑ Pleck, Elizabeth (1979). "Wife Beating in Nineteenth-Century America". Victimology: An International Journal. 4: 64–65.

- ↑ Arnot, Margaret L.; Usborne, Cornelie (2003). Gender and crime in modern Europe ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). London: Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 1-85728-746-0.

- ↑ Green, Nicholas St. John. 1879. Criminal Law Reports: Being Reports of Cases Determined in the Federal and State Courts of the United States, and in the Courts of England, Ireland, Canada, etc. with notes. Hurd and Houghton. "The cases in the American courts are uniform against the right of the husband to use any [physical] chastisement, moderate or otherwise, toward the wife, for any purpose."

- ↑ Feder, Lynette (1999). Women and Domestic Violence: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Haworth Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-7890-0667-7.

- ↑ http://www.thefreelibrary.com/No-drop+prosecution+of+domestic+violence%3A+just+good+policy,+or+equal...-a058511048

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Domestic_violence.aspx

- ↑ National Women's Aid Federation.

- ↑ House of Commons Sitting (1973) Battered Women.

- ↑ "Definitions of Domestic Violence". Childwelfare.gov. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ "South Carolina Legislature Mobile". Scstatehouse.gov. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ http://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/Case_Processing_Report.pdf

- 1 2 Laws on violence against women. Office on Women's Health, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. May 18, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ "PUBLIC LAW 104-208".

- ↑ "Criminal Resource Manual 1117 Restrictions on the Possession of Firearms by Individuals Convicted of a Misdemeanor Crime of Domestic Violence.".

- ↑

- 1 2 http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/30/us/victim-of-domestic-violence-in-guatemala-is-ruled-eligible-for-asylum-in-us.html?_r=0

- ↑ Garner, J.; F. Clemmer (1986). "Danger to Police in Domestic Disturbances—A New Look". Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- ↑ Stanford, M. R.; B. I. Mowry (1990). "Domestic Disturbance Danger Rate". Journal of Police Science and Administration. 17: 244–9.

- ↑ Fagan, Jeffrey (1995). "Criminalization of Domestic Violence: Promises and Limits" (PDF). Research Report. Conference on Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation. National Institute of Justice.

- ↑ Straus, M.; Gelles, R. & Steinmetz, S. (1980). Behind Closed Doors: Violence in the American Family. Anchor/Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-14259-5.

- ↑ Police Foundation (1976). "Domestic Violence and the Police: Studies in Detroit and Kansas City". The Police Foundation.

- ↑ Gelles, R. J. (1993). "Constraints Against Family Violence: How Well Do They Work". American Behavioral Scientist. 36 (5): 575–586. doi:10.1177/0002764293036005003.

- ↑ Sherman, Lawrence W.; Richard A. Berk (1984). "The Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment" (PDF). Police Foundation. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Straus (1980), and references below, "Criticism of police response"

- ↑ Maxwell, Christopher D.; Garner, Joel H.; Fagan, Jefferey A. (2001). "The effects of arrest on intimate partner violence: New evidence from the spouse assault replication program (Research in Brief)" (PDF). National Institute of Justice. NCJ 188199.

- 1 2 Buzawa, E. S.; C. G. Buzawa (1990). Domestic Violence: The Criminal Justice Response. Sage. pp. 94–9. ISBN 0-7619-2448-5.

- ↑ Elliott, Delbert S. (1989). "Criminal Justice Procedures in Family Violence Crimes". In Oblin, Lloyd and Michael Tonry. Family Violence. Crime and Justice: A Review of Research. University of Chicago. pp. 427–80.

- ↑ Hoctor, M. (1997). "Domestic Violence as a Crime against the State". California Law Review. California Law Review, Inc. 85 (3): 643–700. doi:10.2307/3481154. JSTOR 3481154.

- ↑ Carswell, Sue (2006). "Historical development of the pro-arrest policy". Family violence and the pro-arrest policy: a literature review. New Zealand Ministry of Justice.

- 1 2 Schmidt, J. D.; Sherman, L. W. (1993). "Does Arrest Deter Domestic Violence". American Behavioral Scientist. 36 (5): 601–609. doi:10.1177/0002764293036005005.

- ↑ Maryland Network Against Domestic Violence. Mnadv.org. Retrieved on 2011-12-23.

- ↑ Ertük, Yakin. "Integration of the Human Rights of Women and the Gender Perspective: Violence Against Women - The Due Diligence Standard as a Tool for the Elimination of Violence against Women" (PDF). www.refworld.org. United Nations Economics and Social Council. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ Manjoo, Rashida. "Report of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, its causes and consequences, Ms. Rashida Manjoo: Mission to the United States" (PDF). United Nations Human Rights Council. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- 1 2 IACHR report No. 80/11 case 12.626 merits Jessica Lenahan (Gonzales) et al. United States

- ↑ "Cities, Counties, and Human Rights Commissions Across the U.S. Pass Freedom from Domestic Violence Resolutions". American University Washington College of Law. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ "Recognizing Freedom From Domestic Violence and Violence Against Women as a Fundamental Human Right: Local Resolutions, Presidential Proclamations, and Other Statements of Principle" (PDF). University of Miami School of Law. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ "The Status of Human Rights in Tennessee" (PDF). Tennessee Human Rights Commission. November 2014. p. 23. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ "Recognizing Freedom From Domestic Violence and Violence Against Women as a Fundamental Human Right: Local Resolutions, Presidential Proclamations, and Other Statements of Principle". Cornell Law School, Columbia Law School, University of Miami School of Law. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ "Recognizing Freedom From Domestic Violence and Violence Against Women as a Fundamental Human Right: Local Resolutions, Presidential Proclamations, and Other Statements of Principle" (PDF). University of Miami School of Law. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- 1 2 Adams, Carol J.; Fortune, Mary M. (1998). Violence against women and children: a Christian Theologocial Sourcebook. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company. Page 10. ISBN 0-8264-0830-3.

- 1 2 "Mission". www.ncadv.org. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ↑ "Help for Abused and Battered Women: Protecting Yourself and Escaping from Domestic Violence". www.helpguide.org. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ↑ Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) Program Summary. Office on Women's Health, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ Jewish Women International

- ↑ Flood, M. "Men's collective anti-violence activism and the struggle for gender justice". Development. 2001 (44): 42–47.

- ↑ University of Minnesota Duluth conceptual framework

- ↑ "Power and Control Film". Power and Control: Domestic Violence in America. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ↑ Domestic Abuse Intervention Project: History

- ↑ Twohey, Megan (2009-01-02). "How Can Domestic Violence Be Stopped?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

Further reading

- Joanne Carlson Brown; Carold R. Bohn, eds. (1989). Christianity, Patriarchy, and Abuse: A Feminist Critique. New York: Pilgrim. ISBN 0-8298-0808-6.

- Annie Imbens; Ineke Jonker (1992). Christianity and Incest. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-2541-2.

- Carol J. Adams; Marie M. Fortune, eds. (1995). Violence against Women and Children: A Christian Theological Sourcebook. New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-0830-3.

- Marie M. Fortune (1991). Violence in the Family: a Workshop Curriculum for Clergy and Other Helpers. Cleveland: Pilgrim. ISBN 0-8298-0908-2.

- Carolyn Holderread Heggen (1993). Sexual Abuse in Christian Homes and Churches. Scottsdale, Arizona: Herald Press. ISBN 0-8361-3624-1.

- Anne L. Horton; Judith A. Williamson, eds. (1988). Abuse and Religion: When Praying Isn't Enough. Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-669-15337-0.

- Mary D. Pellauer; Barbara Chester; Jane A. Boyajian, eds. (1987). Sexual Assault and Abuse: A Handbook for Clergy and Religious Professionals. San Francisco: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-254810-7.

- Rita-Lou Clarke (1986). Pastoral Care of Battered Women. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. ISBN 0-664-24015-1.

- Shannan M. Catalano. Intimate Partner Violence: Attributes of Victimization, 1993-2011. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2013.

External links

- National Domestic Violence Hotline

- domesticshelters.org searchable online directory of 3,000 domestic violence agencies in U.S., a free service of National Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Theresa's Fund

- FaithTrust Institute (formerly Center for the Prevention of Sexual and Domestic Violence), a multifaith, multicultural training and education organization in the United States with global reach working to end sexual and domestic violence.