Django (web framework)

| |

|

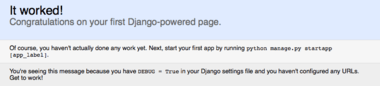

The default Django page | |

| Original author(s) | Lawrence Journal-World |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Django Software Foundation |

| Initial release | 21 July 2005[1] |

| Stable release | 1.10.4[2] (December 1, 2016) [±] |

| Preview release | 1.10 rc 1[3] (July 19, 2016) [±] |

| Repository |

github |

| Development status | Active |

| Written in | Python |

| Size | 6.92 MB |

| Type | Web framework |

| License | 3-clause BSD |

| Website |

www |

Django (/ˈdʒæŋɡoʊ/ JANG-goh)[4] is a free and open-source web framework, written in Python, which follows the model-view-template (MVT) architectural pattern.[5][6] It is maintained by the Django Software Foundation (DSF), an independent organization established as a 501(c)(3) non-profit.

Django's primary goal is to ease the creation of complex, database-driven websites. Django emphasizes reusability and "pluggability" of components, rapid development, and the principle of don't repeat yourself. Python is used throughout, even for settings files and data models. Django also provides an optional administrative create, read, update and delete interface that is generated dynamically through introspection and configured via admin models.

Some well-known sites that use Django include the Public Broadcasting Service,[7] Pinterest,[8] Instagram,[9] Mozilla,[10] The Washington Times,[11] Disqus,[12] Bitbucket,[13] and Nextdoor.[14]

History

Django was born in the fall of 2003, when the web programmers at the Lawrence Journal-World newspaper, Adrian Holovaty and Simon Willison, began using Python to build applications.[15] It was released publicly under a BSD license in July 2005. The framework was named after guitarist Django Reinhardt.[15]

In June 2008, it was announced that a newly formed Django Software Foundation (DSF) would maintain Django in the future.[16]

Features

Components

Despite having its own nomenclature, such as naming the callable objects generating the HTTP responses "views",[5] the core Django framework can be seen as an MVC architecture.[6] It consists of an object-relational mapper (ORM) that mediates between data models (defined as Python classes) and a relational database ("Model"), a system for processing HTTP requests with a web templating system ("View"), and a regular-expression-based URL dispatcher ("Controller").

Also included in the core framework are:

- a lightweight and standalone web server for development and testing

- a form serialization and validation system that can translate between HTML forms and values suitable for storage in the database

- a template system that utilizes the concept of inheritance borrowed from object-oriented programming

- a caching framework that can use any of several cache methods

- support for middleware classes that can intervene at various stages of request processing and carry out custom functions

- an internal dispatcher system that allows components of an application to communicate events to each other via pre-defined signals

- an internationalization system, including translations of Django's own components into a variety of languages

- a serialization system that can produce and read XML and/or JSON representations of Django model instances

- a system for extending the capabilities of the template engine

- an interface to Python's built in unit test framework

Bundled applications

The main Django distribution also bundles a number of applications in its "contrib" package, including:

- an extensible authentication system

- the dynamic administrative interface

- tools for generating RSS and Atom syndication feeds

- a sites framework that allows one Django installation to run multiple websites, each with their own content and applications

- tools for generating Google Sitemaps

- built-in mitigation for cross-site request forgery, cross-site scripting, SQL injection, password cracking and other typical web attacks, most of them turned on by default[17][18]

- a framework for creating GIS applications

Extensibility

Django's configuration system allows third party code to be plugged into a regular project, provided that it follows the reusable app[19] conventions. More than 2500 packages[20] are available to extend the framework's original behavior, providing solutions to issues the original tool didn't: registration, search, API provision and consumption, CMS, etc.

This extensibility is, however, mitigated by internal components dependencies. While the Django philosophy implies loose coupling,[21] the template filters and tags assume one engine implementation, and both the auth and admin bundled applications require the use of the internal ORM. None of these filters or bundled apps are mandatory to run a Django project, but reusable apps tend to depend on them, encouraging developers to keep using the official stack in order to benefit fully from the apps ecosystem.

Server arrangements

Django can be run in conjunction with Apache, NGINX using WSGI, Gunicorn, or Cherokee using flup (a Python module).[22][23] Django also includes the ability to launch a FastCGI server, enabling use behind any web server which supports FastCGI, such as Lighttpd or Hiawatha. It is also possible to use other WSGI-compliant web servers.[24] Django officially supports four database backends: PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQLite, and Oracle. Microsoft SQL Server can be used with django-mssql on Microsoft operating systems,[25] while similarly external backends exist for IBM DB2,[26] SQL Anywhere[27] and Firebird.[28] There is a fork named django-nonrel, which supports NoSQL databases, such as MongoDB and Google App Engine's Datastore.[29]

Django may also be run in conjunction with Jython on any Java EE application server such as GlassFish or JBoss. In this case django-jython must be installed in order to provide JDBC drivers for database connectivity, which also provides functionality to compile Django in to a .war suitable for deployment.[30]

Google App Engine includes support for Django version 1.x.x[31] as one of the bundled frameworks.

Version history

| Meaning | |

|---|---|

| Red | Not supported |

| Yellow | Still supported |

| Green | Current version |

| Version | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 0.90[32] | 16 Nov 2005 | |

| 0.91[33] | 11 Jan 2006 | "new-admin" |

| 0.95[34] | 29 Jul 2006 | "magic removal" |

| 0.96[35] | 23 Mar 2007 | "newforms", testing tools |

| 1.0[36] | 3 Sep 2008 | API stability, decoupled admin, unicode |

| 1.1[37] | 29 Jul 2009 | Aggregates, transaction based tests |

| 1.2[38] | 17 May 2010 | Multiple db connections, CSRF, model validation |

| 1.3[39] | 23 Mar 2011 | Class based views, staticfiles |

| 1.4[40] | 23 Mar 2012 | Timezones, in browser testing, app templates. Long-term support release[41] |

| 1.5[42] | 26 Feb 2013 | Python 3 Support, configurable user model |

| 1.6[43] | 6 Nov 2013 | Dedicated to Malcolm Tredinnick, db transaction management, connection pooling. |

| 1.7[44] | 2 Sep 2014 | Migrations, application loading and configuration. |

| 1.8[45] | 1 Apr 2015 | Native support for multiple template engines. Long-term support release, supported until at least April 2018 |

| 1.9[46] | 1 Dec 2015 | Automatic password validation. New styling for admin interface. |

| 1.10[47] | 1 Aug 2016 | Full text search for PostgreSQL. New-style middleware. |

Development tools with Django support

For developing a Django project, no special tools are necessary, since the source code can be edited with any conventional text editor. Nevertheless, editors specialized on computer programming can help increase the productivity of development, e.g. with features such as syntax highlighting. Since Django is written in Python, text editors which are aware of Python syntax are beneficial in this regard.

Integrated development environments (IDE) add further functionality, such as debugging, refactoring, unit testing, etc. As with plain editors, IDEs with support for Python can be beneficial. Some IDEs that are specialized on Python additionally have integrated support for Django projects, so that using such an IDE when developing a Django project can help further increase productivity. For comparison of such Python IDEs, see the main article:

Community

There is a semiannual conference for Django developers and users, named "DjangoCon", that has been held since September 2008. DjangoCon is held annually in Europe, in May or June;[48] while another is held in the United States in August or September, in various cities.[49] The 2012 DjangoCon took place in Washington D.C from 3 to 8 September. 2013 DjangoCon was held in Chicago at the Hyatt Regency Hotel and the post-conference Sprints were hosted at Digital Bootcamp, computer training center.[50] The 2014 DjangoCon US returned to Portland, WA from 30 August to 6 September. The 2015 DjangoCon US was held in Austin, TX from 6 to 11 September at the AT&T Executive Center. The 2016 DjangoCon US was held in Philadelphia, PA at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania from 17 to 22 July.[51]

Django mini-conferences were held in Hobart, Australia in July 2013, in Brisbane, Australia in August 2014 and 2015, and in Melbourne, Australia in 2016.[52]

Ports to other languages

Programmers have ported Django's template design from Python to other languages, providing decent cross-platform support. Some of these options are more direct ports; others, though inspired by Django and retaining its concepts, take the liberty to deviate from Django's design:

- Swig for JavaScript

- Liquid for Ruby

- Template::Swig for Perl

- Twig for PHP

- Jinja for Python

- ErlyDTL for Erlang

Bibliography

- Roy Greenfeld, Daniel; Roy Greenfeld, Audrey (2015), Two Scoops of Django: Best Practices for Django 1.8 (3rd ed.), Two Scoops Press, p. 531, ISBN 0981467342

- Jaiswal, Sanjeev; Kumar, Ratan (22 June 2015), Learning Django Web Development (1st ed.), Packt, p. 405, ISBN 1783984406

- Ravindrun, Arun (31 March 2015), Django Design Patterns and Best Practices (1st ed.), Packt, p. 180, ISBN 1783986646

- Osborn, Tracy (May 2015), Hello Web App (1st ed.), Tracy Osborn, p. 142, ISBN 0986365912

- Bendoraitis, Aidas (October 2014), Web Development with Django Cookbook (1st ed.), Packt, p. 294, ISBN 178328689X

- Baumgartner, Peter; Malet, Yann (2015), High Performance Django (1st ed.), Lincoln Loop, p. 184, ISBN 1508748128

- Elman, Julia; Lavin, Mark (2014), Lightweight Django (1st ed.), O'Reilly Media, p. 246, ISBN 149194594X

- Percival, Harry (2014), Test-Driven Development with Python (1st ed.), O'Reilly Media, p. 480, ISBN 1449364829

This list is an extraction from Current Django Books

External links

- Official website

- Django Official Documentation - Current and detailed documentation on nearly every aspect of Django. It includes a version selector for information pertaining to specific versions of Django.

- Two Scoops Press Curated List of Django Tutorials - A comprehensive list of up-to-date Django tutorials.

- Tango with Django - A beginner's tutorial to web development with Django.

- Taskbuster - A tutorial for experienced coders who want to learn Django.

- Django Packages - A directory of reusable apps, sites, tools, and more for Django projects.

- Django Girls official tutorial . Tutorial was built in mind for people starting learning programming.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Django (web framework). |

References

- ↑ "Django FAQ". Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ↑ Graham, Tim (1 December 2016). "Django bugfix release issued: 1.10.4, 1.9.12, 1.8.17". Django Weblog. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Graham, Tim (18 July 2016). "Django security releases issued: 1.10 release candidate 1, 1.9.8, and 1.8.14". Django Weblog. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ "FAQ: General - Django documentation - Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- 1 2 "FAQ: General - Django documentation - Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- 1 2 Adrian Holovaty, Jacob Kaplan-Moss; et al. The Django Book.

Django follows this MVC pattern closely enough that it can be called an MVC framework

- ↑ "20 Creative Websites Running Django".

- ↑ "What is the technology stack behind Pinterest?". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "What Powers Instagram: Hundreds of Instances, Dozens of Technologies".

- ↑ "Python". Mozilla Developer Network. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Opensource.washingtontimes.com. Retrieved on 2014-05-30.

- ↑ "Scaling Django to 8 Billion Page Views".

- ↑ "DjangoSuccessStoryBitbucket – Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "The anti-Facebook: one in four American neighborhoods are now using this private social network". The Verge. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Django's History". The Django Book. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ "Announcing the Django Software Foundation - Weblog - Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Security in Django". Django Project. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ Socol, James (2012). "Best Basic Security Practices (Especially with Django)". Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "What is a reusable app? — django-reusable-app-docs 0.1.0 documentation". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Django Packages". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Design philosophies - Django documentation - Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Django documentation of deployment

- ↑ "Cherokee Web Server - Cookbook Setting up Django - Cherokee Documentation". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ How to use Django with Apache and mod_wsgi. Official Django documentation.

- ↑ "Manfre / django-mssql / source / — Bitbucket". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ ibmdb. "GitHub - ibmdb/python-ibmdb: Automatically exported from code.google.com/p/ibm-db". GitHub. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Google Code Archive - Long-term storage for Google Code Project Hosting.". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ maxirobaina. "GitHub - maxirobaina/django-firebird: Firebird SQL backend for django". GitHub. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Django non-rel". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ beachmachine. "GitHub - beachmachine/django-jython: Database backends and extensions for Django development on top of Jython.". GitHub. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Running Pure Django Projects on Google App Engine. Code.google.com (2010-11-01). Retrieved on 5 December 2011.

- ↑ "Introducing Django 0.90". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django 0.91 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Introducing Django 0.95". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Announcing Django 0.96!". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django 1.0 released!". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django 1.1 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django 1.2 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django 1.3 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django 1.4 released". Django weblog. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django's release process - Django documentation - Django". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "Django 1.5 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ "Django 1.6 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ "Django 1.7 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "Django 1.8 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ "Django 1.9 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Django 1.10 released" Django weblog. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ DjangoCon EU series, Lanyrd.com

- ↑ DjangoCon US series, Lanyrd.com

- ↑ "DjangoCon". DjangoCon. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "DjangoCon". DjangoCon. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ DjangoCon AU. Djangocon.com.au. Retrieved on 2016-09-23.