Discrimination against intersex people

| Intersex topics |

|---|

| Human rights and legal issues |

| Events |

| Medicine and biology |

| Society and history |

|

| Lists |

| See also |

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, or genitals that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies";[1] "Because their bodies are seen as different, intersex children and adults are often stigmatized and subjected to multiple human rights violations".[1]

Discriminatory treatment includes infanticide, abandonment, mutilation and neglect, as well as broader concerns regarding right to life.[2][3] Intersex people face discrimination in education, employment, healthcare, sport, with an impact on mental and physical health, and on poverty levels, including as a result of harmful medical practices.[4]

The United Nations, African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, Council of Europe, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and other human rights institutions, have called for countries to ban discrimination and combat stigma.[5] Few countries so far protect intersex people from discrimination, or provide access to reparations for harmful practices.[2][6]

Protection from discrimination

A 2013 first international pilot study. Human Rights between the Sexes, by Dan Christian Ghattas, found that intersex people are discriminated against worldwide: "Intersex individuals are considered individuals with a «disorder» in all areas in which Western medicine prevails. They are more or less obviously treated as sick or «abnormal», depending on the respective society."[7][8]

The United Nations states that intersex people suffer stigma on the basis of physical characteristics, "including violations of their rights to health and physical integrity, to be free from torture and ill-treatment, and to equality and non- discrimination."[1] The UN has called for governments to end discrimination against intersex people:

Ban discrimination on the basis of sex characteristics, intersex traits or status, including in education, health care, employment, sports and access to public services, and consult intersex people and organizations when developing legislation and policies that impact their rights.[9]

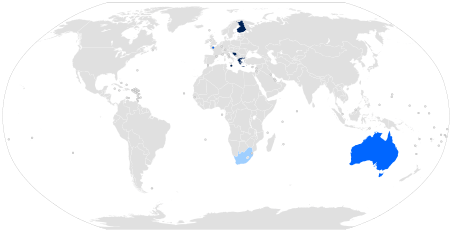

A handful of jurisdictions so far provide explicit protection from discrimination for intersex people. South Africa was the first country to explicitly add intersex to legislation, as part of the attribute of 'sex'.[10] Australia was the first country to add an independent attribute, of 'intersex status'.[11] Malta was the first to adopt a broader framework of "sex characteristics", through legislation that also ended modifications to the sex characteristics of minors undertaken for social and cultural reasons.[12] Since then, Bosnia-Herzegovina has prohibited discrimination based on "sex characteristics",[13][14] and Greece has prohibited discrimination and hate crimes based on "sex characteristics" since 24 December 2015.[15][16]

Right to life

Intersex people face genetic de-selection via pregnancy terminations and preimplantation genetic diagnosis, as well as abandonment, neglect, infanticide and murder due to their sex characteristics. In 2015, the Council of Europe published an Issue Paper on Human rights and intersex people, remarking:

Intersex people’s right to life can be violated in discriminatory “sex selection” and “preimplantation genetic diagnosis, other forms of testing, and selection for particular characteristics”. Such de-selection or selective abortions are incompatible with ethics and human rights standards due to the discrimination perpetrated against intersex people on the basis of their sex characteristics.[2]

In 2015, Chinese news reported a case of abandonment of an infant, thought likely due to its sex characteristics.[17] Hong Kong activist Small Luk reports that this is not uncommon, in part due to the historic imposition of a policy of one child per family.[18] Cases of infanticide, attempted infanticide, and neglect have been reported in China,[19] Uganda[3][20] and Pakistan.[21]

Kenyan reports suggest that the birth of an intersex infant may be viewed as a curse.[22] In 2015, it was reported that an intersex Kenyan adolescent, Muhadh Ishmael, was mutilated and later died. Ishmael had previously been described as a curse on his family.[23]

Healthcare

In places with accessible healthcare systems, intersex people face harmful practices including involuntary or coercive treatment, and in places without such systems, infanticide, abandonment and mutilation may occur.[24]

Harmful practices

Intersex people face harmful practices including involuntary or coerced medical treatment from infancy.[25][26] Where these occur without personal informed consent, these are "violations of their rights to health and physical integrity, to be free from torture and ill-treatment, and to equality and non- discrimination."[1][5]

A 2016 Australian study of 272 people born with atypical sex characteristics found that 60% had received medical treatment on the basis of their sex characteristics, half receiving such treatments aged under 18 years, "most commonly genital surgeries (many of which occurred in infancy) and hormone treatments", and the "majority experienced at least one negative impact".[27] Overall, while some parents and physicians had attempted to empower participants, the study found "strong evidence suggesting a pattern of institutionalised shaming and coercive treatment" and poor (or no) information provision.[4] 16% of study participants were not provided with information on options of having no treatment, and some were provided with misinformation about the nature of their treatment, and information about peer support was also lacking.

A Germany study conducted between 2005 and 2007 found that 81% of 439 participants had received surgical interventions due to their sex characteristics, and two-thirds of the adult participants in the study "drew a connection between sexual problems and their history of surgical treatment. Participating children reported significant disturbances, especially within family life and physical well-being – these are areas that the medical and surgical treatment was supposed to stabilize."[28]

Rationales for medical intervention frequently focus on parental distress, or problematize future gender identity and sexuality, and subjective judgements are made about the acceptability of risk of future gender dysphoria[29][30] Medical professionals have traditionally considered the worst outcomes after genital reconstruction in infancy to occur when the person develops a gender identity discordant with the sex assigned as an infant. Human rights institutions question such approaches as being "informed by redundant social constructs around gender and biology"[31]

Decision-making on any cancer and other physical risks may be intertwined with "normalizing" rationales. In a major Parliamentary report in Australia, published in October 2013, the Senate Community Affairs References committee was "disturbed" by the possible implications of current practices in the treatment of cancer risk. The committee stated: "clinical intervention pathways stated to be based on probabilities of cancer risk may be encapsulating treatment decisions based on other factors, such as the desire to conduct normalising surgery… Treating cancer may be regarded as unambiguously therapeutic treatment, while normalising surgery may not. Thus basing a decision on cancer risk might avoid the need for court oversight in a way that a decision based on other factors might not. The committee is disturbed by the possible implications of this..."[26]

Despite the naming of clinician statements as "consensus" statements, there remains no clinical consensus about the conduct of surgical interventions,[26] nor their evidence base, surgical timing, necessity, type of surgical intervention, and degree of difference warranting intervention.[30][32][33] Surgery may adversely impact physical sensation and capacity for intimacy,[28][33] however, research has suggested that parents are willing to consent to appearance-altering surgeries even at the cost of later adult sexual sensation.[34] Other research shows that parents may make different choices with non-medicalized information.[35] Child rights experts suggest that parents have no right to consent to such treatments.[36]

Clinical decision-making is frequently portrayed as a choice between early or later surgical interventions, while human rights advocates and some clinicians portray concerns as matters of consent and autonomy.[33][37]

Medical photography and display

Photographs of intersex children's genitalia are circulated in medical communities for documentary purposes, and individuals with intersex traits may be subjected to repeated genital examinations and display to medical teams. Sharon Preves described this as a form of humiliation and stigmatization, leading to an "inability to deflect negative associations of self" where "genitalia must be revealed in order to allow for stigmatization".[38][39][40] According to Creighton et al, the "experience of being photographed has exemplified for many people with intersex conditions the powerlessness and humiliation felt during medical investigations and interventions".[40]

Access to medical services

Adults with intersex variations report poor mental health due to experiences of medicalization,[41] with many individuals avoiding care as a result. Many Australian study participants stated a need to educate their physicians. Similar reports are made elsewhere: reports on the situation Mexico suggests that adults may not receive adequate care, including lack of understanding about intersex bodies and examinations that cause physical harm.[42][43]

In countries without accessible healthcare systems, infanticide, abandonment and mutilation may occur.[24] Access to necessary medical services, for example due to cancer or urinary issues, is also limited.[20][43][44]

Suicidality and self-harm

The impact of discrimination and stigma can also be seen in high rates of suicidal tendencies and self harm. Multiple anecdotal reports, including from Hong Kong and Kenya point to high levels of suicidality amongst intersex people.[18][22] The Australian sociological study of 272 people born with atypical sex characteristics found that 60% had thought about suicide, and 42% thought about self-harm, "on the basis of issues related to having an intersex variation ... 19% had attempted suicide"; causes identified included stigma, discrimination, "family rejection and school bullying.[45]

A 2013 German clinical study found high rates of distress, with "prevalence rates of self-harming behavior and suicidal tendencies ... comparable to traumatized women with a history of physical or sexual abuse."[46] Similar results have been reported in Australia[46] and Denmark.[41]

Education

An Australian sociological survey of 272 persons born with atypical sex characteristics, published in 2016, found that 18% of respondents (compared to an Australian average of 2%) failed to complete secondary school, with early school leaving coincident with pubertal medical interventions, bullying on the basis of physical characteristics, and other factors.[45] A Kenyan news report suggests high rates of early school leaving, with the organisation Gama Africa reporting that 60% of 132 known intersex people had dropped out of school "because of the harassment and treatment they received from their peers and their teachers".[22]

The Australian study found that schools lacked inclusive services such as relevant puberty and sex education curricula and counselling, for example, not representing a full range of human bodily diversity. Only a quarter of respondents felt positive about their schooling experiences, and early school leaving peaked "during the years most associated with puberty and hormone therapy interventions".[45] Cognitive differences may also be associated with some traits such as sex chromosome variations.[47] Nevertheless, in addition to very high rates of early school leaving, the Australian study also found that a higher proportion of study participants completed undergraduate or postgraduate degrees compared to the general Australian population.[45]

Poverty and employment discrimination

The impact of discrimination and stigma can be seen in high rates of poverty. A 2015 Australian survey of people born with atypical sex characteristics found high levels of poverty, in addition to very high levels of early school leaving, and higher than average rates of disability.[4] 6% of the 272 survey participants reported being homeless or couch surfing.[45]

OII Europe states that "stigma, structural and verbal discrimination, harassment" as well as harmful practices and lack of legal recognition can lead to "inadequate education, broken careers and poverty (including homelessness) due to pathologisation and related trauma, a disturbed family life due to taboo and medicalisation, lack of self-esteem and a high risk of becoming suicidal."[48]

An Employers guide to intersex inclusion published by Pride in Diversity and Organisation Intersex International Australia discloses cases of discrimination in employment.[49]

Legal

Like all individuals, some intersex individuals may be raised as a particular sex (male or female) but then identify with another later in life, while most do not.[50][51][52] Like non-intersex people, some intersex individuals may not identify themselves as either exclusively female or exclusively male. A 2012 clinical review suggests that between 8.5-20% of persons with intersex conditions may experience gender dysphoria,[29] while sociological research in Australia, a country with a third 'X' sex classification, shows that 19% of people born with atypical sex characteristics selected an "X" or "other" option, while 52% are women, 23% men and 6% unsure.[4][27]

Depending on the jurisdiction, access to any birth certificate may be an issue,[53] including a birth certificate with a sex marker.[54] The Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions states that:

Recognition before the law means having legal personhood and the legal protections that flow from that. For intersex people, this is neither primarily nor solely about amending birth registrations or other official documents. Firstly, it is about intersex people who have been issued a male or a female birth certificate being able to enjoy the same legal rights as other men and women[6]

Access to a birth certificate with a correct sex marker may be an issue for people who do not identify with their sex assigned at birth,[2] or it may only be available accompanied by surgical requirements.[6]

The passports and identification documents of Australia and some other nationalities have adopted "X" as a valid third category besides "M" (male) and "F" (female), at least since 2003.[55][56] In 2013, Germany became the first European nation to allow babies with characteristics of both sexes to be registered as indeterminate gender on birth certificates, amidst opposition and skepticism from intersex organisations who point out that the law appears to mandate exclusion from male or female categories.[57][58][59] The Council of Europe acknowledged this approach, and concerns about recognition of third and blank classifications in a 2015 Issue Paper, stating that these may lead to "forced outings" and "lead to an increase in pressure on parents of intersex children to decide in favour of one sex."[2] The Issue Paper argues that "further reflection on non-binary legal identification is necessary".

Sport

Women who have, or are perceived to have intersex traits are subject to stigmatization, humiliation and trial by media.[60][61][62] Currently suspended IAAF regulations on hyperandrogenism "mandated that national Olympic committees "actively investigate any perceived deviation in sex characteristics"" in women athletes.[61]

In 2013, it was disclosed in a medical journal that four unnamed elite female athletes from developing countries were subjected to gonadectomies (sterilization) and partial clitoridectomies (female genital mutilation) after testosterone testing revealed that they had an intersex condition.[61][63] Testosterone testing was introduced in the wake of the Caster Semenya case, of a South African runner subjected to testing due to her appearance and vigor.[61][63][64][65] There is no evidence that innate hyperandrogenism in elite women athletes confers an advantage in sport.[66][67] While Australia protects intersex persons from discrimination, the Act contains an exemption in sport.

LGBT

Intersex people may face discrimination within LGBT settings and multiple organizations have highlighted appeals to LGBT rights recognition that fail to address the issue of unnecessary "normalising" treatments on intersex children, using the portmanteau term "pinkwashing". Emi Koyama has described how inclusion of intersex in LGBTI can fail to address intersex-specific human rights issues, including creating false impressions "that intersex people's rights are protected" by laws protecting LGBT people, and failing to acknowledge that many intersex people are not LGBT.[68] Julius Kaggwa of SIPD Uganda has written that, while the gay community "offers us a place of relative safety, it is also oblivious to our specific needs".[69] Mauro Cabral has written that transgender people and organizations "need to stop approaching intersex issues as if they were trans issues" including use of intersex as a means of explaining being transgender; "we can collaborate a lot with the intersex movement by making it clear how wrong that approach is".[70]

Organisation Intersex International Australia states that some intersex individuals are same sex attracted, and some are heterosexual, but "LGBTI activism has fought for the rights of people who fall outside of expected binary sex and gender norms"[71][72] but, in June 2016, the same organization pointed to contradictory statements by Australian governments, suggesting that the dignity and rights of LGBTI (LGBT and intersex) people are recognized while, at the same time, harmful practices on intersex children continue.[73] In August 2016, Zwischengeschlecht described actions to promote equality or civil status legislation without action on banning "intersex genital mutilations" as a form of pinkwashing.[74] The organization has previously highlighted evasive government statements to UN Treaty Bodies that conflate intersex, transgender and LGBT issues, instead of addressing harmful practices on infants.[75]

Prohibitions of discrimination

Australia

"Intersex status" became a protected attribute in the federal Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act on 1 August 2013, distinguishing intersex status from gender identity, sexual orientation, sex, and disability. It defines intersex as:[11][76]

intersex status means the status of having physical, hormonal or genetic features that are:(a) neither wholly female nor wholly male; or (b) a combination of female and male; or (c) neither female nor male.[11]

The Act facilitates exemptions in competitive sport but does not support exemptions on religious grounds.[77][78]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Since August 1, 2016 Bosnia-Herzegovina anti-discrimination laws explicetly protect intersex people, that is listed as "sex characteristics".[13][14]

Finland

Since 2015, the Act on Equality between Women and Men includes "gender features of the body" within its definition of gender identity and gender expression, which are the prohibited grounds under the act, meaning that discrimination on these basics is prohibited.[79][80]

Greece

Since 24 December 2015, Greece prohibits discrimination and hate crimes based on "sex characteristics".[15][16]

Jersey

Since 1 September 2015, Discrimination (Jersey) Law 2013 includes intersex status within its definition of sex. Sex is one of the prohibited grounds under the act, meaning that discrimination on this basis is prohibited. The act provides that:

"Sex"(1) Sex is a protected characteristic.

(2) In relation to the protected characteristic –

(a) a reference to a person who has that characteristic is a reference to a man, a woman or a person who has intersex status;

(b) a reference to persons who share the characteristic is a reference to persons who are of the same sex.

(3) In this paragraph, a person has intersex status if the person has physical, chromosomal, hormonal or genetic features that are –

(a) neither wholly male or female;

(b) a combination of male or female; or

(c) neither male nor female— Discrimination (Jersey) Law 2013, Schedule 1, as amended[81]

Malta

In April 2015, Malta passed a Gender Identity Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act that protects intersex people from discrimination on grounds of "sex characteristics", and also recognizes a right to bodily integrity and physical autonomy.[82]

"sex characteristics" refers to the chromosomal, gonadal and anatomical features of a person, which include primary characteristics such as reproductive organs and genitalia and/or in chromosomal structures and hormones; and secondary characteristics such as muscle mass, hair distribution, breasts and/or structure.[82]

The Act was widely welcomed by civil society organizations.[12][83][84][85][86]

South Africa

In South Africa, the Judicial Matters Amendment Act, 2005 (Act 22 of 2005) amended the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act, 2000 (Act 4 of 2000) to include intersex within its definition of sex.[10] Sex is one of the prohibited grounds under the act, meaning that unfair discrimination on the basis of sex is prohibited. The act provides that:

'intersex' means a congenital sexual differentiation which is atypical, to whatever degree;'sex' includes intersex;

— Act 4 of 2000, section 1, as amended[87]

United States

In May 2016, the United States Department of Health and Human Services issued a statement explaining Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act stating that the Act prohibits "discrimination on the basis of intersex traits or atypical sex characteristics" in publicly-funded healthcare, as part of a prohibition of discrimination "on the basis of sex".[88][89]

See also

- Sex characteristics

- Intersex human rights

- Intersex medical interventions

- Legal recognition of intersex people

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 "Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex" (PDF). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Council of Europe; Commissioner for Human Rights (April 2015), Human rights and intersex people, Issue Paper

- 1 2 Richter, Ruthann (March 4, 2014). "In Uganda, offering support for those born with indeterminate sex". Stanford Medicine.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones, Tiffany; Hart, Bonnie; Carpenter, Morgan; Ansara, Gavi; Leonard, William; Lucke, Jayne (February 2016). Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-208-0. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- 1 2 Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (October 24, 2016), Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October. End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge

- 1 2 3 Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions (June 2016). Promoting and Protecting Human Rights in relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Sex Characteristics. Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions. ISBN 978-0-9942513-7-4.

- ↑ Ghattas, Dan Christian; Heinrich Böll Foundation (September 2013). "Human Rights Between the Sexes" (PDF).

- ↑ "A preliminary study on the life situations of inter* individuals". OII Europe. 4 November 2013.

- ↑ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. "United Nations for Intersex Awareness". Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- 1 2 "Judicial Matters Amendment Act, No. 22 of 2005, Republic of South Africa, Vol. 487, Cape Town" (PDF). 11 January 2006.

- 1 2 3 "Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013, No. 98, 2013, C2013A00098". ComLaw. 2013.

- 1 2 Cabral, Mauro (April 8, 2015). "Making depathologization a matter of law. A comment from GATE on the Maltese Act on Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics". Global Action for Trans Equality. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- 1 2 "Anti-discrimination Law Updated in Bosnia-Herzegovina". ILGA-Europe.

- 1 2 "LGBTI people are now better protected in Bosnia and Herzegovina".

- 1 2 (Greek) "NOMOΣ ΥΠ' ΑΡΙΘ. 3456 Σύμφωνο συμβίωσης, άσκηση δικαιωμάτων, ποινικές και άλλες διατάξεις".

- 1 2 (Greek)"Πρώτη φορά, ίσοι απέναντι στον νόμο".

- ↑ Lau, Mimi (August 24, 2015). "Baby born with male and female genitals found abandoned in Chinese park". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- 1 2 Luk, Small (October 20, 2015), Beyond boundaries: intersex in Hong Kong and China, Intersex Day

- ↑ Free Press Journal Bureau (June 22, 2016). "Terming intersex baby a 'monster', father attempts to murder". Free Press Journal.

- 1 2 Kaggwa, Julius (2016-10-09). "Understanding intersex stigma in Uganda". Intersex Day. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ Warne, Garry L.; Raza, Jamal (September 2008). "Disorders of sex development (DSDs), their presentation and management in different cultures". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 9 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1007/s11154-008-9084-2. ISSN 1389-9155.

- 1 2 3 Odhiambo, Rhoda (October 20, 2016). "Kenya to mark international intersex day next week". The Star, Kenya. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ↑ Odero, Joseph (December 23, 2015). "Intersex in Kenya: Held captive, beaten, hacked. Dead.". 76 CRIMES. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- 1 2 Carpenter, Morgan (May 2016). "The human rights of intersex people: addressing harmful practices and rhetoric of change". Reproductive Health Matters. 24 (47): 74–84. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2016.06.003. ISSN 0968-8080. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics NEK-CNE (November 2012). On the management of differences of sex development. Ethical issues relating to "intersexuality".Opinion No. 20/2012 (PDF). 2012. Berne.

- 1 2 3 Australian Senate Community Affairs Committee (October 2013). "Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia".

- 1 2 Organisation Intersex International Australia (July 28, 2016). "Demographics". Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- 1 2 Cabral, Mauro; Carpenter, Morgan, eds. (2014). Intersex Issues in the International Classification of Diseases: a revision (PDF).

- 1 2 Furtado P. S.; et al. (2012). "Gender dysphoria associated with disorders of sex development". Nat. Rev. Urol. 9 (11): 620–627. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2012.182. PMID 23045263.

- 1 2 Mouriquand, Pierre D. E.; Gorduza, Daniela Brindusa; Gay, Claire-Lise; Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F. L.; Baker, Linda; Baskin, Laurence S.; Bouvattier, Claire; Braga, Luis H.; Caldamone, Anthony C.; Duranteau, Lise; El Ghoneimi, Alaa; Hensle, Terry W.; Hoebeke, Piet; Kaefer, Martin; Kalfa, Nicolas; Kolon, Thomas F.; Manzoni, Gianantonio; Mure, Pierre-Yves; Nordenskjöld, Agneta; Pippi Salle, J. L.; Poppas, Dix Phillip; Ransley, Philip G.; Rink, Richard C.; Rodrigo, Romao; Sann, Léon; Schober, Justine; Sibai, Hisham; Wisniewski, Amy; Wolffenbuttel, Katja P.; Lee, Peter. "Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: If (why), when, and how?". Journal of Pediatric Urology. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.001. ISSN 1477-5131. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ↑ Australian Human Rights Commission (June 2015). Resilient Individuals: Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity & Intersex Rights. Sydney. ISBN 978-1-921449-71-0.

- ↑ Lee, Peter A.; Nordenström, Anna; Houk, Christopher P.; Ahmed, S. Faisal; Auchus, Richard; Baratz, Arlene; Baratz Dalke, Katharine; Liao, Lih-Mei; Lin-Su, Karen; Looijenga, Leendert H.J.; Mazur, Tom; Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F.L.; Mouriquand, Pierre; Quigley, Charmian A.; Sandberg, David E.; Vilain, Eric; Witchel, Selma; and the Global DSD Update Consortium (2016-01-28). "Global Disorders of Sex Development Update since 2006: Perceptions, Approach and Care". Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 85 (3). doi:10.1159/000442975. ISSN 1663-2818. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- 1 2 3 Creighton, Sarah M.; Michala, Lina; Mushtaq, Imran; Yaron, Michal (January 2, 2014). "Childhood surgery for ambiguous genitalia: glimpses of practice changes or more of the same?". Psychology and Sexuality. 5 (1): 34–43. doi:10.1080/19419899.2013.831214. ISSN 1941-9899. Retrieved 2015-07-19.

- ↑ Dayner, Jennifer E.; Lee, Peter A.; Houk, Christopher P. (October 2004). "Medical Treatment of Intersex: Parental Perspectives". The Journal of Urology. 172 (4): 1762–1765. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000138519.12573.3a. ISSN 0022-5347.

- ↑ Streuli, Jürg C.; Vayena, Effy; Cavicchia-Balmer, Yvonne; Huber, Johannes (August 2013). "Shaping Parents: Impact of Contrasting Professional Counseling on Parents' Decision Making for Children with Disorders of Sex Development". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 10 (8): 1953–1960. doi:10.1111/jsm.12214. ISSN 1743-6095.

- ↑ Sandberg, Kirsten (October 2015). "The Rights of LGBTI Children under the Convention on the Rights of the Child". Nordic Journal of Human Rights. 33 (4): 337–352. doi:10.1080/18918131.2015.1128701. ISSN 1891-8131.

- ↑ Tamar-Mattis, A. (August 2014). "Patient advocate responds to DSD surgery debate". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 10 (4): 788–789. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.03.019. ISSN 1477-5131.

- ↑ Preves, Sharon Elaine (July 2000). "Negotiating the Constraints of Gender Binarism: Intersexuals' Challenge to Gender Categorization". Current Sociology. 48 (3): 27–50. doi:10.1177/0011392100048003004.

- ↑ Preves, Sharon (2003). Intersex and Identity, the Contested Self. Rutgers. ISBN 0-8135-3229-9. p. 72.

- 1 2 Creighton, Sarah; Alderson, J; Brown, S; Minto, Cathy (2002). "Medical photography: ethics, consent and the intersex patient". BJU international (89). pp. 67–71.p. 70.

- 1 2 Liao, Lih-Mei; Simmonds, Margaret (2013). "A values-driven and evidence-based health care psychology for diverse sex development". Psychology & Sexuality. 5 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1080/19419899.2013.831217. ISSN 1941-9899.

- ↑ Inter, Laura (2015). "Finding My Compass". Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics. 5 (2): 95–98.

- 1 2 Inter, Laura (October 3, 2016). "The situation of the intersex community in Mexico". Intersex Day. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ↑ Regmi, Esan (2016). Stories of Intersex People from Nepal (PDF). Kathmandu.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jones, Tiffany (March 11, 2016). "The needs of students with intersex variations". Sex Education: 1–17. doi:10.1080/14681811.2016.1149808. ISSN 1468-1811. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 Schützmann, Karsten; Brinkmann, Lisa; Schacht, Melanie; Richter-Appelt, Hertha (February 2009). "Psychological Distress, Self-Harming Behavior, and Suicidal Tendencies in Adults with Disorders of Sex Development". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 38 (1): 16–33. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9241-9. ISSN 0004-0002.

- ↑ Hong, D. S.; Hoeft, F.; Marzelli, M. J.; Lepage, J.-F.; Roeltgen, D.; Ross, J.; Reiss, A. L. (March 5, 2014). "Influence of the X-Chromosome on Neuroanatomy: Evidence from Turner and Klinefelter Syndromes". Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (10): 3509–3516. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2790-13.2014. ISSN 0270-6474. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ↑ OII Europe. "European Intersex Visibility Works!". Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ↑ Carpenter, Morgan; Hough, Dawn (2014). Employers' Guide to Intersex Inclusion. Sydney, Australia: Pride in Diversity and Organisation Intersex International Australia. ISBN 978-0-646-92905-7.

- ↑ Money, John; Ehrhardt, Anke A. (1972). Man & Woman Boy & Girl. Differentiation and dimorphism of gender identity from conception to maturity. USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-1405-7.

- ↑ Domurat Dreger, Alice (2001). Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex. USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00189-3.

- ↑ Marañón, Gregorio (1929). Los estados intersexuales en la especie humana. Madrid: Morata.

- ↑ "Kenya takes step toward recognizing intersex people in landmark ruling". Reuters.

- ↑ Viloria, Hida (November 6, 2013). "Op-ed: Germany's Third-Gender Law Fails on Equality". The Advocate.

- ↑ Holme, Ingrid (2008). "Hearing People's Own Stories". Science as Culture. doi:10.1080/09505430802280784. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "New Zealand Passports - Information about Changing Sex / Gender Identity". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Third sex option on birth certificates". Deutsche Welle. 1 November 2013.

- ↑ "Sham package for Intersex: Leaving sex entry open is not an option". OII Europe. 15 February 2013.

- ↑ "'X' gender: Germans no longer have to classify their kids as male or female". RT. 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Karkazis, Katrina (August 23, 2016). "The ignorance aimed at Caster Semenya flies in the face of the Olympic spirit". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Jordan-Young, R. M.; Sonksen, P. H.; Karkazis, K. (April 2014). "Sex, health, and athletes". BMJ. 348 (apr28 9): –2926–g2926. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2926. ISSN 1756-1833. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- ↑ Macur, Juliet (6 October 2014). "Fighting for the Body She Was Born With". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- 1 2 Fénichel, Patrick; Paris, Françoise; Philibert, Pascal; Hiéronimus, Sylvie; Gaspari, Laura; Kurzenne, Jean-Yves; Chevallier, Patrick; Bermon, Stéphane; Chevalier, Nicolas; Sultan, Charles (June 2013). "Molecular Diagnosis of 5α-Reductase Deficiency in 4 Elite Young Female Athletes Through Hormonal Screening for Hyperandrogenism". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 98 (6): –1055–E1059. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3893. ISSN 0021-972X. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ "Semenya told to take gender test". BBC Sport. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ↑ "A Lab is Set to Test the Gender of Some Female Athletes.". New York Times. 30 July 2008.

- ↑ Bermon, Stéphane; Garnier, Pierre Yves; Lindén Hirschberg, Angelica; Robinson, Neil; Giraud, Sylvain; Nicoli, Raul; Baume, Norbert; Saugy, Martial; Fénichel, Patrick; Bruce, Stephen J.; Henry, Hugues; Dollé, Gabriel; Ritzen, Martin (August 2014). "Serum Androgen Levels in Elite Female Athletes". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism: –2014–1391. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1391. ISSN 0021-972X. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Branch, John (27 July 2016). "Dutee Chand, Female Sprinter With High Testosterone Level, Wins Right to Compete". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ Koyama, Emi. "Adding the "I": Does Intersex Belong in the LGBT Movement?". Intersex Initiative. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Kaggwa, Julius (September 19, 2016). "I'm an intersex Ugandan – life has never felt more dangerous". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ↑ Cabral, Mauro (October 26, 2016). "IAD2016: A Message from Mauro Cabral". GATE - Global Action for Trans Equality. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ↑ Organisation Intersex International Australia (November 21, 2012). "Intersex for allies". Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ OII releases new resource on intersex issues, Intersex for allies and Making services intersex inclusive by Organisation Intersex International Australia, via Gay News Network, 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Submission: list of issues for Australia's Convention Against Torture review". Organisation Intersex International Australia. June 28, 2016.

- ↑ ""Intersex legislation" that allows the daily mutilations to continue = PINKWASHING of IGM practices". Zwischengeschlecht. August 28, 2016.

- ↑ "TRANSCRIPTION > UK Questioned over Intersex Genital Mutilations by UN Committee on the Rights of the Child - Gov Non-Answer + Denial". Zwischengeschlecht. May 26, 2016.

- ↑ "On the historic passing of the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 25 June 2013.

- ↑ "Australian Parliament, Explanatory Memorandum to the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Bill 2013". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "We welcome the Senate Inquiry report on the Exposure Draft of the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill 2012". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 21 February 2013.

- ↑ (Finnish)"Laki naisten ja miesten välisestä tasa-arvosta annetun lain muuttamisesta".

- ↑ Ghattas, Dan Christian; ILGA-Europe (2016). "Standing up for the human rights of intersex people – how can you help?" (PDF).

- ↑ "DISCRIMINATION (SEX AND RELATED CHARACTERISTICS) (JERSEY) REGULATIONS 2015". 2015.

- 1 2 Malta (April 2015), Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act: Final version

- ↑ Star Observer (2 April 2015). "Malta passes law outlawing forced surgical intervention on intersex minors". Star Observer.

- ↑ OII Europe (April 1, 2015). "OII-Europe applauds Malta's Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act. This is a landmark case for intersex rights within European law reform". Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ↑ Carpenter, Morgan (April 2, 2015). "We celebrate Maltese protections for intersex people". Organisation Intersex International Australia. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ↑ Transgender Europe (April 1, 2015). Malta Adopts Ground-breaking Trans and Intersex Law – TGEU Press Release.

- ↑ "Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act No. 4 of 2000, as amended" (PDF). 2000.

- ↑ interACT. "Federal Government Bans Discrimination Against Intersex People in Health Care". interactadvocates. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ↑ Office for Civil Rights (OCR) (2016). "Section 1557 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act" (Text). HHS.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-27.