Dioscorus of Aphrodito

| Dioscorus of Aphrodito | |

|---|---|

|

Anonymous Mummy Portrait from the Fayyum | |

| Born |

Dioskoros c. A.D. 520 Aphrodito, Egypt |

| Died |

c. A.D. 585 Aphrodito, Egypt |

| Occupation | Poet, lawyer, village administrator |

| Nationality | Coptic |

| Citizenship | Egyptian |

| Literary movement | Allegory |

| Notable works | Hymn to St. Theodosius (Poem 17) |

| Relatives | Apollos (father) |

Flavius Dioscorus (Greek: Φλαύϊος Διόσκορος Flauios Dioskoros) lived during the 6th century A.D. in the village of Aphrodito, Egypt, and therefore is called by modern scholars Dioscorus of Aphrodito.[1] Although he was an Egyptian, he composed poetry in Greek, the cultural language of the Byzantine Era.[2] His poems are the oldest surviving poems written by the hand of a known poet.[3] The manuscripts, which contain his corrections and revisions, were discovered on papyrus in 1905,[4] and are now held in museums and libraries around the world.[5] Dioscorus was also occupied in legal work, and legal documents and drafts involving him, his family, Aphroditans, and others were discovered along with his poetry.[6] As an administrator of the village of Aphrodito, he composed petitions on behalf of its citizens, which are unique for their poetic and religious qualities.[7] Dioscorus was a Christian (a Copt) and lived in a religiously active environment.[8] The collection of Greek and Coptic papyri associated with Dioscorus and Aphrodito is one of the most important finds in the history of papyrology and has shed considerable light on the law and society of Byzantine Egypt.[9]

Papyrus

The papyri of Dioscorus were discovered by accident in July 1905 in the village of Kom Ashkaw (also called Kom Ishgau, Kom Ishqaw, etc.), which was built above the ancient site of Aphrodito.[10] An inhabitant was renovating his home when a wall collapsed and revealed a chasm below. Papyrus rolls and fragments were seen in the crevice, but by the time the Antiquities Service was notified and arrived, most of the papyrus was gone. During subsequent excavations, a large jar filled with papyrus was discovered in a Roman-style house. Important fragments of Athenian Comedy, both Old and New, were discovered among these papyri, including fragments of the famous comedy writer Menander.[11] There were also fragments of Homer's Iliad and other literary works and reference works.[12]

Most importantly, the excavator Gustave Lefebvre unearthed an archive of sixth-century legal, business, and personal papers, and original poetry. These were turned over to the young scholar Jean Maspero, son of the Director of the Antiquities Service of Egypt, who edited and published the documents and poems in several journal articles [13] and two volumes of the Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire: Papyrus grecs d’époque byzantine (Cairo 1911, 1913). Jean was killed in the battle at Vauquois on the Lorraine during World War I, and his father Gaston completed the third volume of Dioscorian papyri in 1916. Other Dioscorian papyri, obtained by antiquities dealers through sales and clandestine excavations,[14] were published in Florence, London, Paris, Strasbourg, Princeton, Ann Arbor, the Vatican, etc.[15]

Aphrodito

The village of Kom Ashkaw is in Middle Egypt, south of Cairo and north of Luxor. It was originally an Egyptian city, but after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 B.C., it was given the Greek name "Aphroditopolis" (“The City of Aphrodite”) and was made the capital city of its nome (an administrative district, like a US county). Before the 6th century, however, Aphroditopolis lost its status as a city, and the capital of the nome was moved across the Nile River to Antaeopolis.[16] The village of Aphrodito and the city of Antaeopolis were part of a larger, merged administrative district called the Thebaid, which was under the jurisdiction of a doux, appointed by the Byzantine Emperor. The doux had his administrative center in Antinoopolis on the east bank of the Nile River.[17]

.jpg)

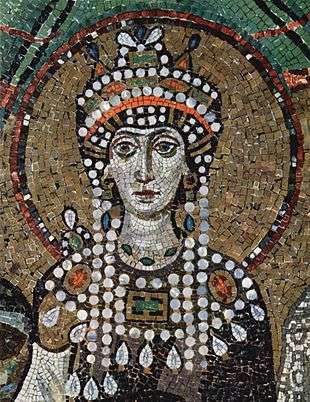

6th century representation of the Mother of God as a Byzantine Empress.

Aphrodito was situated in an environment that was highly poetic and religious. Nonnus, the most influential poet of the Early Byzantine Era (A.D. 300–700), had come from Panopolis, 42 km. southeast of Aphrodito.[18] Other poets from the Thebaid had not only become celebrities—such as Musaeus Grammaticus, Colluthus, and Christodorus—but also were part of a poetic revolution of that time.[19] These poets, though Egyptians, wrote their verses in the Greek dialect of Homer, who had composed his Iliad and Odyssey more than a thousand years before them. Perhaps one of the reasons for this movement was to usurp the pagan vocabulary and style of the most honored ancient poet for Christian purposes. Dioscorus continued and developed this revolution by writing encomiastic poems (poems of praise) in an Homeric style.[20] The community was also active religiously. According to the New Testament, Egypt was the first home of young Jesus and his family.[21] And according to Patristic literature, Egypt was the birthplace of Christian monasticism.[22] In Northern Egypt, the areas of Nitria, Kellia, and Wadi Natrun contained large monastic centers that attracted devout followers from both the Eastern and Western halves of the Byzantine Empire.[23] In southern Egypt, one of the first Christian monasteries was established at Pbow, 127 km. southeast of Aphrodito.[24] Less than 40 km. south of Aphrodito was the White Monastery, founded by the vigorous Coptic monk Shenoute.[25] The father of Dioscorus himself, Apollos, established and later entered his own monastery.[26] In fact, Aphrodito and its vicinity “boasted over thirty churches and nearly forty monasteries.”[27]

Biography

Early years

There is no surviving record for the early years of Dioscorus. His father Apollos was an entrepreneur and local official.[28] The commonly accepted date for the birth of Dioscorus is around A.D. 520.[29] Although there is no evidence, it is likely that Dioscorus went to school in Alexandria, where one of his teachers might have been the Neoplatonic philosopher John Philoponus.[30] Although Alexandria was not the most prominent place for a legal education – that was the city of Beirut – young men did travel there for rhetorical training preliminary to the study of law.[31] These included the celebrated poet Agathias, a contemporary of Dioscorus, who at an early age published a successful collection of poems called the Cycle and later became the center of a circle of prominent poets in Constantinople.[32]

Back in Aphrodito, Dioscorus married, had children, and pursued a career similar to his father's: acquiring, leasing out, and managing property, and helping in the administration of the village.[33] His first dated appearance in the papyrus is 543. Dioscorus had the assistant of the defensor civitatis of Antaeopolis examine the damage done by a shepherd and his flock to a field of crops, which was owned by the Monastery of Apa Sourous but managed by Dioscorus.[34]

Constantinople

6th century representation of the Empress Theodora.

Dioscorus also became engaged in legal work. In 546/7, after his father Apollos died, Dioscorus wrote a formal petition to Emperor Justinian and a formal explanation to Empress Theodora about tax conflicts affecting Aphrodito.[35] The village was under the special patronage of the Empress,[36] and had been granted the status of autopragia.[37] This meant that the village could collect its own public taxes and deliver them directly to the imperial treasury. Aphrodito was not under the jurisdiction of the pagarch, stationed in Antaeopolis, who handled the public taxes for the rest of the nome.[38] Dioscorus's petition and explanation to the imperial palace described the pagarch's violations of their special tax status, including theft of the collected tax money.

The communications to Constantinople seem to have had little effect, and in 551 (three years after the death of Theodora), Dioscorus travelled with a contingency of Aphroditans to Constantinople to present the problem to the Emperor directly. Dioscorus may have spent three years in the capital of the Byzantine Empire.[39] In poetry, the city was very active. Not only was Agathias now writing there, but also Paul the Silentiary and Romanus the Melodist. In respect to the Aphroditans' tax problems, Dioscorus was able to obtain an imperial rescript, three copies of which have survived in his archive.[40] The Emperor instructs the Duke of the Thebaid to investigate and, if justified, to stop the aggressions of the pagarch. There is no evidence of further tax violations by the pagarch until after the death of Justinian in 565.

Antinoopolis

6th century representation of St. Peter as a Roman consul.

In 565/6 Dioscorus left Aphrodito for Antinoopolis, the capital city of the Thebaid and the residence of the doux.[41] He remained there for about seven years. His motivation for the move is nowhere made clear. But surmising from the surviving documents, one can conclude that he was attracted by the opportunity to advance his legal career in the proximity of the Duke and likewise was compelled by the increasing violence of the pagarch against Aphrodito and his own family.[42] The legal documents from that period show that Dioscorus wrote the final will for the Surgeon General (Phoebammon),[43] arbitrated in family property disputes,[44] composed marriage and divorce contracts,[45] and continued writing petitions about the offenses of the pagarch. One such petition, P.Cair.Masp. I 67002, describes how a group of Aphroditans on their way to the annual cattle market were ambushed. They were eventually put into a prison in Antaeopolis, under the control of the pagarch Menas, where they were tortured and robbed and their animals were seized. Menas and his men then attacked the village of Aphrodito itself: he blocked the irrigation, extorted money, burned down homes, and violated the nuns. All these crimes were committed in the name of collecting the public taxes, although Aphrodito had never failed a payment and Menas had no right to collect them. A formal explanation, P.Lond. V 1677, describes the attacks by Menas on Dioscorus himself and his family. He seized property owned by Dioscorus and transferred it to his assistants, leaving Dioscorus with only the tax liability. Menas proceeded to pillage the home of Dioscorus's brother-in-law and seized his land too, reducing him and his family to poverty. He then arrested Dioscorus's own son.

Before May 574, Dioscorus left Antinoopolis.[46] The reason for his departure is not explained. It might have been related to domestic affairs, to his career, or to the changed situation in Constantinople. The violent crimes against Aphrodito and Dioscorus (described above) were committed under the reign of Justin II, who had launched a savage persecution of Christians that did not adhere to Chalcedonian dogmas, including Egyptian Copts. But Justin went completely insane and abdicated, and in 574, Tiberius and Empress Sophia, the wife of Justin, took over the management of the Byzantine Empire.

Return to Aphrodito

Back home in Aphrodito, it seems that Dioscorus withdrew from legal affairs and administrative responsibilities. Much of his poetry was composed during his stay in Antinoopolis or after he had returned to Aphrodito.[47] His documents now focus on mundane, rural activities. His last dated document, a land lease written by his hand in an account book, is April 5, 585.[48]

6th century representation of the Virgin Mary as a Byzantine Empress.

Poetry

Publications

Dioscorus might have recited his poems and circulated them locally, but there is no evidence that they were ever published during his lifetime. Jean Maspero published the first collection of Dioscorian poems in 1911: “Un dernier poète grec d’Égypte: Dioscore, fils d’Apollôs.”[49] This journal article included the texts of 13 poems, French translations, and an analysis of the style. Then between 1911 and 1916, Jean and Gaston Maspero republished the poems along with Dioscorian documents in three volumes of Papyrus grecs d'époque byzantine.[50] These poems were all part of the papyrus collection owned by the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In 1962, Ernst Heitsch published 29 Dioscorian poems that were among papyrus fragments held in a variety of museums and libraries.[51] For over thirty-five years, this was the authoritative edition. The most comprehensive edition at the present time is by Jean-Luc Fournet, who in 1999 published 51 Dioscorian poems and fragments (including 2 that he considered of dubious authenticity).[52] In addition to the texts and commentaries offered by Maspero, Heitsch, Fournet, and the initial editors of other poems, a comprehensive study of his poetry was published by Leslie MacCoull in 1988: Dioscorus of Aphrodito: His Work and His World (Berkeley). Clement Kuehn published a reinterpretation of his poetry in 1995: Channels of Imperishable Fire: The Beginnings of Christian Mystical Poetry and Dioscorus of Aphrodito (New York).

6th century representation of martyrs dressed as Roman senators.

Interpretations

The reactions by modern readers to his poetry have varied widely. The papyrologists and historians that first examined them were not impressed. Influenced by their backgrounds in Classical poetry, they compared the Dioscorian verses primarily to Classical standards. The most frequent objection was that his verses were obscure: the editors thought that the lines did not make sense – or at least, were not saying what the editors expected them to say.[53] A more positive assessment was offered by Leslie MacCoull, who insisted that a reader must take Dioscorus’s Coptic background into consideration when reading the poetry.[54] Many of the poems seemed to be praising unknown dignitaries – including an Emperor and several Dukes – and some papyrologists concluded that Dioscorus wrote the poems to get favors from government administrators (whom the papyrologists vaguely and inconsistently identified).[55] Clement Kuehn, however, proposed that the poems be viewed not from a Classical, Hellenistic, or even a strictly Egyptian perspective,[56] but through a lens of Byzantine culture and spirituality, in which Dioscorus and the Thebaid were so deeply immersed. Kuehn demonstrated that the poems fit neatly and masterfully into the allegorical style that was pervasive in the pictoral art and literature of the Early Byzantine Era.[57] That is: Dioscorus, influenced by allegorical commentaries on the Homeric epics and Bible, and by the allegorical icons and church art of the 6th century, was praising Christ, Old Testament patriarchs, and the saints in heaven as if they were the Emperor, kings, and dignitaries in a Byzantine court.[58]

References

General

- Bagnall, Roger S., ed. 2007. Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700. Cambridge.

- ----- 2009. The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford.

- Bagnall, Roger, and Dominic Rathbone, eds. 2004. Egypt from Alexander to the Early Christians: An Archaeological and Historical Guide. Los Angeles.

- Bell, H. I. 1917. Greek Papyri in the British Museum, Vol. V. London. [P.Lond. V]

- ----- 1944. “An Egyptian Village in the Age of Justinian.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 64: 21–36.

- Bell, H. I., and W. E. Crum. 1925. “A Greek-Coptic Glossary.” Aegyptus 6: 177–226.

- Cameron, Alan. 1965. “Wandering Poets: A Literary Movement in Byzantine Egypt.” Historia 14: 470–509.

- ----- 2007. “Poets and Pagans in Byzantine Egypt.” In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. by R. Bagnall, Cambridge, 21–46.

- Cameron, Averil. 1970. Agathias. Oxford.

- Cameron, Alan and Averil. 1966. “The Cycle of Agathias.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 86: 6–25.

- Cavero, Laura Miguélez. 2008. Poems in Context: Greek Poetry in the Egyptian Thebaid 200–600 AD. Berlin.

- Countryman, L. William. 1997. Review of Channels of Imperishable Fire: The Beginnings of Christian Mystical Poetry and Dioscorus of Aphrodito, by Clement A. Kuehn. In Church History 66 (4): 787–789.

- Cribiore, Raffaella. 2007. “Higher Education in Early Byzantine Egypt: Rhetoric, Latin, and the Law.” In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. by R. Bagnall, Cambridge, 47–66.

- Dawson, D. 1992. Allegorical Readers and Cultural Revision in Ancient Alexandria. Berkeley.

- Gomme, A. W., and F. H. Sandbach. 1973. Menander: A Commentary. Oxford.

- Emmel, S. 2004. Shenoute’s Literary Corpus. 2 vols. Leuven.

- Feissel, Denis, and Jean Gascou, eds. 2004. La pétition à Byzance. Paris.

- Fournet, J.-L. 1999. Hellénisme dans l’Égypte du VIe siècle. La bibliothèque et l’œuvre de Dioscore d’Aphrodité. MIFAO 115. 2 vols. Cairo.

- Fournet, Jean-Luc, and Caroline Magdelaine, eds. 2008. Les archives de Dioscore d’Aphrodité cent ans après leur découverte: histoire et culture dans l’Egypte byzantine : actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 8–10 décembre 2005. Paris.

- Gagos, T., and P. van Minnen. 1994 . Settling a Dispute: Toward a Legal Anthropology of Late Antique Egypt. Ann Arbor.

- Gascou, Jean. 1972. “La détention collégiale de l’autorité pagarchique.” Byzantion 43 (1972): 60–72.

- ----- 1976. “P.Fouad 87: les monastères pachômiens et l’état byzantin,” BIFAO 76: 157–84.

- ----- 1981. “Documents grecs relatifs au monastère d’Abba Apollôs.” Anagennesis 1 (2): 219–30.

- Grossmann, Peter. 2002. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten. Leiden.

- ----- 2007. “Early Christian Architecture in Egypt and its Relationship to the Architecture of the Byzantine World.” In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. by R. Bagnall, Cambridge, 103-36.

- ----- 2008. “Antinoopolis Oktober 2007. Vorläufiger Bericht über die Arbeiten”; and “Antinoopolis Januar/Februar 2008. Vorläufiger Bericht über die Arbeiten.” In Aegyptus: Rivista Italiana di Egittologia e di Papirologia, Milan, n.p.

- Heitsch, Ernst. 1963. Die griechischen Dichterfragmente der römischen Kaiserzeit. Vol. 1, 2nd edn. Göttingen.

- ----- 1964. Die griechischen Dichterfragmente der römischen Kaiserzeit. Vol. 2. Göttingen.

- Keenan, James G. 1984a. “The Aphrodite Papyri and Village Life in Byzantine Egypt.” Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 26: 51–63.

- ----- 1984b. “Aurelius Apollos and the Aphrodite Village Élite.” In Atti del XVII congresso internazionale di papirologia, by the Centro Internazionale per lo Studio dei Papiri Ercolanesi, vol. 3, 957–63. Naples.

- ----- 1985. “Village Shepherds and Social Tension in Byzantine Egypt.” Yale Classical Studies 28: 245–59.

- ----- 1988. Review of Dioscorus of Aphrodito, His Work and His World, by Leslie S. B. MacCoull. In Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 25: 173–78.

- ----- 2000. “Egypt.” In The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 14: Late Antiquity, Empire and Successors, A.D. 425–600, 612–37.

- ----- 2007. “Byzantine Egyptian Villages.” In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. R. Bagnall, Cambridge, 226-43.

- ----- 2008. “‘Tormented Voices’: P.Cair.Masp. I 67002.” in Les archives de Dioscore d’Aphrodité, Paris, 171-80.

- ----- 2009. “The History of the Discipline.” In The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology, Oxford, 59–78.

- Koenen, Ludwig, et al. 1978. The Cairo Codex of Menander. London.

- Kovelman, Arkady B. 1991. “From Logos to Myth: Egyptian Petitions of the 5th–7th Centuries.” Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 28: 135–52.

- Kuehn, Clement A. 1990. “Dioskoros of Aphrodito and Romanos the Melodist.” Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 27: 103–07.

- ----- 1993. “A New Papyrus of a Dioscorian Poem and Marriage Contract: P.Berol.Inv.No. 21334.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 97: 103–15; plates 2–3. [SB XXII 15633]

- ----- 1995. Channels of Imperishable Fire: The Beginnings of Christian Mystical Poetry and Dioscorus of Aphrodito. New York.

- ----- 2009. “Egypt at Empire’s End.” The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 46 (1): 175–89.

- ----- 2011. Cicada: The Poetry of the Dioscorus of Aphrdito. The Critical Edition. Vol. 1, part 1. http://www.ByzantineEgypt.com.

- Lamberton, Robert. 1986. Homer the Theologian: Neoplatonist Allegorical Reading and the Growth of the Epic Tradition. Berkeley.

- Lefebvre, Gustave. 1907. Fragments d’un manuscrit de Ménandre. Cairo.

- ----- 1911. Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire, No. 43227: Papyrus de Ménandre. Cairo.

- Liebeschuetz, J.H.W.G. 1973. “The Origin of the Office of the Pagarch.” Byzantinische Zeitschrift 66: 38–46.

- ----- 1974. “The Pagarch: City and Imperial Administration in Byzantine Egypt.” Journal of Juristic Papyrology 18: 163–68.

- MacCoull, Leslie S. B. 1981. “The Coptic Archive of Dioscorus of Aphrodito.” Chronique d’Égypte 56: 185–93.

- ----- 1986. “Further Notes on the Greek-Coptic Glossary of Dioscorus of Aphrodito.” Glotta 64: 253–57.

- ----- 1987. “Dioscorus of Aphrodito and John Philoponus.” Studia Patristica 18 (Kalamazoo): 163-68.

- ----- 1988. Dioscorus of Aphrodito: His Work and His World. Berkeley.

- ----- 1991. “Dioscorus.” The Coptic Encyclopedia, edited by A. Atiya, vol. 3, 916. New York.

- ----- 2006. “The Historical Context of John Philoponus’ De Opificio Mundi in the Culture of Byzantine-Coptic Egypt.” Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum 9 (2): 397–423.

- ----- 2007. “Philosophy in its Social Context.” In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. by R. Bagnall, Cambridge, 67–82.

- ----- 2010a. “Philoponus and the Coptic Eucharist.” Journal of Late Antiquity 3 (1): 158–175.

- ----- 2010b. “Why and How Was the Aphrodito Cadaster Made?” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 50 (4): 625–638.

- Maspero, Jean. 1908–10. “Études sur les papyrus d’Aphrodité I.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’Archéologie Orientale 6 (1908): 75–120. “Études sur les papyrus d’Aphrodité II.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’Archéologie Orientale 7 (1910): 97–119.

- ----- 1910. “Un papyrus littéraire d’Ἀφροδίτης κώμη.” Byzantinische Zeitschrift 19: 1–6.

- ----- 1911. “Un dernier poète grec d’Égypte: Dioscore, fils d’Apollôs.” Revue des études grecques 24: 426–81.

- ----- 1911–1916. Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire: Papyrus grecs d’époque byzantine. 3 vols. Cairo. [P.Cair.Masp.]

- ----- 1912. “Les papyrus Beaugé.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’Archéologie Orientale 10: 131–57.

- McNamee, Kathleen. 2007. Annotations in Greek and Latin Texts from Egypt. New Haven.

- Milne, H. J. M. 1927. Catalogue of the Literary Papyri in the British Museum. London.

- van Minnen, Peter. 2007. “The Other Cities in Later Roman Egypt.” In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. by R. Bagnall, Cambridge, 207-25.

- Parca, Maryline G. 1991. Ptocheia or Odysseus in Disguise at Troy (P. Köln VI 245). Atlanta.

- Rousseau, P. 1985. Pachomius: The Making of a Community in Fourth-Century Egypt. Berkeley.

- Ruffini, Giovanni. 2008. Social Networks in Byzantine Egypt. Cambridge.

- ----- 2011. A Prosopography of Byzantine Aphrodito. Durham, N.C.

- Saija, Ausilia. 1995. Lessico dei carmi di Dioscoro di Aphrodito. Messina.

- Salomon, Richard G. 1948. “A Papyrus from Constantinople (Hamburg Inv. No. 410).” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 34: 98–108, plate XVIII.

- Viljamaa, Toivo. 1968. Studies in Greek Encomiastic Poetry of the Early Byzantine Period. Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum, vol. 42. Helsinki.

- Weitzmann, Kurt. 1978. The Icon. New York.

- Wifstrand, Albert. 1933. Von Kallimachos zu Nonnos: Metrisch-Stilistische Untersuchungen zur späteren griechischen Epik und zu verwandten Gedichtgattungen. Lund.

- Zuckerman, Constantine. 2004. Du village à l’Empire: autour du registre fiscal d’Aphroditô (525/526). Paris.

Specific

- ↑ Kuehn 1995, p. 1.

- ↑ Kuehn 1995, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Parca 1991, 3–4.

- ↑ Maspero 1911, pp. 454–456.

- ↑ Keenan 1984a, p. 53.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, p. 4; Fournet-Magdelaine 2008, pp. 310–343.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, pp. 16–19 and ff.; Kovelman 1991, pp. 138–148; Kuehn 1995, pp. 2–4.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, pp. 5–7; Kuehn 1995, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Bell-Crum 1925, p. 177; Kuehn 1995, p. 47; Ruffini 2008, pp. 150–197.

- ↑ Lefebvre 1907, pp. viii–xi.

- ↑ Lefebvre 1907, 1911; Gomme-Sandbach 1973; Koenen 1978.

- ↑ Fournet 1999, pp. 9–237; Fournet-Magdelaine 2008, pp. 309–310.

- ↑ Maspero 1908–1910, 1910, 1911, 1912.

- ↑ Gaston Maspero, intro. to P.Cair.Masp. III, p. viii; Keenan 1984a, pp. 52–53, and 2009, p. 66; Gagos-van Minnen 1994, p. 8.

- ↑ See note 5 above.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, p. 6; Kuehn 1995, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Bagnall-Rathbone 2004, pp. 169–172.

- ↑ Alan Cameron 2007; pp. 34–39; Cavero 2008, pp. 15–25.

- ↑ Alan Cameron 1965 passim; MacCoull 1988, pp. 59–61; Cavero 2008, pp. 25–105.

- ↑ MacCoull 1985, p. 9; Fournet 1999, pp. 673–675.

- ↑ Mt 2:13–21.

- ↑ Athanasius, Life of Antony.

- ↑ Bagnall-Rathbone 2004, pp. 107–115.

- ↑ Gascou 1976, pp. 157–184; Rousseau 1985 passim.

- ↑ Emmel 2004 passim.

- ↑ Gascou 1981, pp. 219–230.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, p. 7.

- ↑ Keenan 1984b passim; Kuehn 1995, pp. 54–58.

- ↑ Maspero 1911, p. 457; MacCoull 1988, p. 9; Kuehn 1995, p. 59.

- ↑ MacCoull 1987 passim.

- ↑ Cribiore 2007, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Alan and Averil Cameron 1966, pp. 8–10; Averil Cameron 1970 1–11, 140–141.

- ↑ Keenan 1988, p. 173; Kuehn 1995, p. 59.

- ↑ Maspero, P.Cair.Masp. I 67087; Keenan 1985, pp. 245–259.

- ↑ Maspero, P.Cair.Masp. I 67019 v, and P.Cair.Masp. III 67283.

- ↑ Maspero, intro. to P.Cair.Masp. III 67283, pp. 15–17; Bell 1944, p. 31; Keenan 1984a, p. 54.

- ↑ Kuehn 1995, p. 53 note 58.

- ↑ Gascou 1972, pp. 60–72; Liebeschuetz 1973, pp. 38–46, and 1974, pp. 163–168.

- ↑ Salomon 1948, pp. 98 – 108; Fournet 1999, pp. 318 – 321.

- ↑ Maspero, P.Cair.Masp. I 67024 r, v, and 67025.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, pp. 11–12; Kuehn 1995, p. 66.

- ↑ Kuehn 1995, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Maspero, P.Cair.Masp. II 67151 and 67152.

- ↑ Bell, P.Lond. V 1708.

- ↑ Kuehn 1993, pp. 103–106, and 1995, p. 70 note 153.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, p. 14; Kuehn 1995, p. 74.

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, pp. 13–14; Kuehn 1995, pp. 73, 75–76; Fournet 1999, pp. 321–324.

- ↑ Maspero, P.Cair.Masp. III 67325 IV r 5.

- ↑ Revue des études grecques 24: 426–81.

- ↑ Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire: Papyrus grecs d’époque byzantine, 3 vols. (Cairo, 1911–1916). [P.Cair.Masp. I–III]

- ↑ Die griechischen Dichterfragmente der römischen Kaiserzeit, Vol. 1, 2nd edn. (Göttingen, 1963); Vol. 2 (Göttingen, 1964).

- ↑ Hellénisme dans l’Égypte du VIe siècle. La bibliothèque et l’œuvre de Dioscore d’Aphrodité [MIFAO 115], 2 vols. (Cairo 1999).

- ↑ “Le style de Dioscore fait pauvre figure” (Maspero 1911, p. 472; cf. 427). “At no moment has he any real control of thought, diction, grammar, metre, or meaning” (Milne 1927, p. 68). “So ist doch selbst dort, wo der Text heil zu sein scheint, der Gedankengang nicht immer verständlich” (Heitsch 1963, p. 16 note 1).

- ↑ MacCoull 1988, pp. 57–63.

- ↑ “C’est que, pour Dioscore, la poésie semble ne se concevoir que dans l’adversité : elle est destinée à obtenir, non à donner” (Fournet 1999, p. 325).

- ↑ “To be sure, most of these poems are not great works of literature, especially when compared with their illustrious classical models” (Gagos-van Minnen 1994, p. 20).

- ↑ Weitzmann 1978, pp. 40–55; Lamberton 1986 passim; Dawson 1992 passim.

- ↑ Kuehn 1995, pp. 2, 156, and passim; Kuehn 2011, pp. 9–12 (“Introduction”).

External links

- Man and Circumstance Biography of Dioscorus of Aphrodito

- Cicada The Poetry of Dioscorus of Aphrodito: The Critical Edition

- AWOL The Ancient World Online (see July 14, 2011)

- Papy-L What's New in Papyrology (see March 30, 2011)