Diorama

The word diorama /ˌdaɪəˈrɑːmə/ can either refer to a 19th-century mobile theatre device, or, in modern usage, a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle modeling, miniature figure modeling, or aircraft modeling.

Etymology

The word "diorama" originated in 1823 as a type of picture-viewing device, from the French in 1822. The word literally means "through that which is seen", from the Greek di- "through" + orama "that which is seen, a sight". The diorama was invented by Daguerre and Charles Marie Bouton, first exhibited in London September 29, 1823. The meaning "small-scale replica of a scene, etc." is from 1902.[1]

Daguerre's diorama consisted of a piece of material painted on both sides. When illuminated from the front, the scene would be shown in one state and by switching to illumination from behind another phase or aspect would be seen. Scenes in daylight changed to moonlight, a train travelling on a track would crash, or an earthquake would be shown in before and after pictures.

The modern diorama

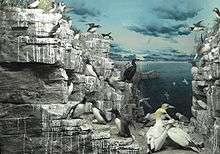

The current, popular understanding of the term "diorama" denotes a partially three-dimensional, full-size replica or scale model of a landscape typically showing historical events, nature scenes or cityscapes, for purposes of education or entertainment.

One of the first uses of dioramas in a museum was in Stockholm, Sweden, where the Biological Museum opened in 1893. It had several dioramas, over three floors. They were also implemented by the National Museum Grigore Antipa from Bucharest Romania and constituted a source of inspiration for many important museums in the world (such as the Museum of Natural History of New York and the Great Oceanographic Museum in Berlin) [reference below].

Miniatures

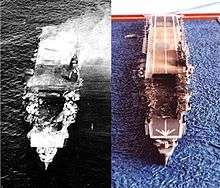

Miniature dioramas are typically much smaller, and use scale models and landscaping to create historical or fictional scenes. Such a scale model-based diorama is used, for example, in Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry to display railroading. This diorama employs a common model railroading scale of 1:87 (HO scale). Hobbyist dioramas often use scales such as 1:35 or 1:48.

Sheperd Paine, a prominent hobbyist, popularized the modern miniature diorama beginning in the 1970s.

Full size dioramas

Modern museum dioramas may be seen in most major natural history museums. Typically, these displays use a tilted plane to represent what would otherwise be a level surface, incorporate a painted background of distant objects, and often employ false perspective, carefully modifying the scale of objects placed on the plane to reinforce the illusion through depth perception in which objects of identical real-world size placed farther from the observer appear smaller than those closer. Often the distant painted background or sky will be painted upon a continuous curved surface so that the viewer is not distracted by corners, seams, or edges. All of these techniques are means of presenting a realistic view of a large scene in a compact space. A photograph or single-eye view of such a diorama can be especially convincing since in this case there is no distraction by the binocular perception of depth.

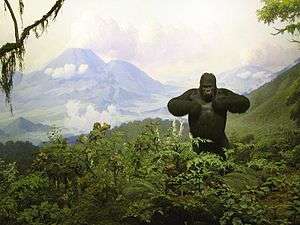

Carl Akeley, a naturalist, sculptor, and taxidermist, is credited with creating the first ever habitat diorama in the year 1889. Akeley's diorama featured taxidermied beavers in a three-dimensional habitat with a realistic, painted background. With the support of curator Frank M. Chapman, Akeley designed the popular habitat dioramas featured at the American Museum of Natural History. Combining art with science, these exhibitions were intended to educate the public about the growing need for habitat conservation. The modern AMNH Exhibitions Lab is charged with the creation of all dioramas and otherwise immersive environments in the museum.[2]

Uses

Miniature dioramas may be used to represent scenes from historic events. A typical example of this type are the dioramas to be seen at Norway's Resistance Museum in Oslo, Norway.

Landscapes built around model railways can also be considered dioramas, even though they often have to compromise scale accuracy for better operating characteristics.

Hobbyists also build dioramas of historical or quasi-historical events using a variety of materials, including plastic models of military vehicles, ships or other equipment, along with scale figures and landscaping.

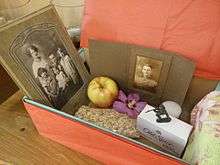

In the 19th and beginning 20th century, building dioramas of sailing ships had been a popular handcraft of mariners. Building a diorama instead of a normal model had the advantage that in the diorama, the model was protected inside the framework and could easily be stowed below the bunk or behind the sea chest. Nowadays, such antique sailing ship dioramas are valuable collectors' items.

One of the largest dioramas ever created was a model of the entire State of California built for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 and that for a long time was installed in San Francisco's Ferry Building.

Dioramas are widely used in the American educational system, mostly in elementary and middle schools. They are often made to represent historical events, ecological biomes, cultural scenes, or to visually depict literature. They are usually made from a shoebox and contain a trompe-l'œil in the background contrasted with two or three-dimensional models in the foreground.

Historic dioramas

The Daguerre Dioramas

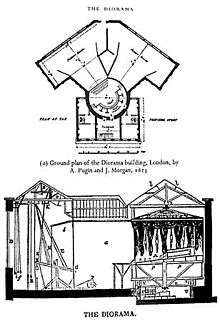

The Diorama was a popular entertainment that originated in Paris in 1822. An alternative to the also popular "Panorama" (panoramic painting), the Diorama was a theatrical experience viewed by an audience in a highly specialized theatre. As many as 350 patrons would file in to view a landscape painting that would change its appearance both subtly and dramatically. Most would stand, though limited seating was provided. The show lasted 10 to 15 minutes, after which time the entire audience (on a massive turntable) would rotate to view a second painting. Later models of the Diorama theater even held a third painting.

The size of the proscenium was 24 feet (7.3 m) wide by 21 feet (6.4 m) high (7.3 meters x 6.4 meters). Each scene was hand-painted on linen, which was made transparent in selected areas. A series of these multi-layered, linen panels were arranged in a deep, truncated tunnel, then illuminated by sunlight re-directed via skylights, screens, shutters, and colored blinds. Depending on the direction and intensity of the skillfully manipulated light, the scene would appear to change. The effect was so subtle and finely rendered that both critics and the public were astounded, believing they were looking at a natural scene.

The inventor and proprietor of the Diorama was Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851), formerly a decorator, manufacturer of mirrors, painter of Panoramas, and designer and painter of theatrical stage illusions. Daguerre would later co-invent the daguerreotype, the first widely used method of photography.

A second Diorama building in Regent's Park in London was opened by an association of Englishmen (having a contract to purchase Daguerre's tableaux) in 1823, a year after the debut of Daguerre's Paris original. The building which exhibited the diorama was designed by Augustus Charles Pugin, father of the notable English architect and designer Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. The show was a popular sensation, and spawned immediate imitations. British artists like Clarkson Stanfield and David Roberts produced ever-more elaborate (moving) dioramas through the 1830s; sound effects and even living performers were added. Some "typical diorama effects included moonlit nights, winter snow turning into a summer meadow, rainbows after a storm, illuminated fountains," waterfalls, thunder and lightning, and ringing bells.[3] A diorama painted by Daguerre is currently housed in the church of the French town Bry-sur-Marne, where he lived and died.[4][5]

- Daguerre diorama exhibitions (R.D. Wood, 1993)

Exhibition venues : Paris (Pa.1822-28) : London (Lo.1823-32) : Liverpool (Li.1827-32) : Manchester (Ma.1825-27) : Dublin (Du.1826-28) : Edinburgh (Ed.1828-36)

- The Valley of Sarnen :: (Pa.1822-23) : (Lo.1823-24) : (Li.1827-28) : (Ma.1825) : (Du.1826-27) : (Ed. 1828-29 & 1831)

- The Harbour of Brest :: (Pa.1823) : (Lo.1824-25 & 1837) : (Li.1825-26) : (Ma.1826-27) : (Ed. 1834-35)

- The Holyrood Chapel :: (Pa.1823-24) : (Lo.1825) : (Li.1827-28) : (Ma.1827) : (Du.1828) : (Ed.1829-30)

- The Roslin Chapel :: (Pa.1824-25) : (Lo.1826-27) : (Li.1828-29) : (Du.1827-28) : (Ed.1835)

- The Ruins in a Fog :: (Pa.1825-26) : (Lo.1827-28) : (Ed.1832-33)

- The Village of Unterseen :: (Pa.1826-27) : (Lo.1828-29) : (Li.1832) : (Ed.1833-34 & 1838)

- The Village of Thiers :: (Pa.1827-28) : (Lo.1829-30) : (Ed. 1838-39)

- The Mont St. Godard :: (Pa.1828-29) : (Lo.1830-32) : (Ed.1835-36)

The Gottstein Dioramas

Until 1968 Britain boasted a large collection of dioramas. These collections were originally housed in the Royal United Services Institute Museum, (formerly the Banqueting House), in Whitehall. However, when the museum closed, the various exhibits and their 15 known dioramas were distributed to smaller museums throughout England, some ending up in Canada and elsewhere. These dioramas were the brainchild of the wealthy furrier Otto Gottstein (1892–1951) of Leipzig, a Jewish immigrant from Hitler’s Germany, who was an avid collector and designer of flat model figures called flats. In 1930, Gottstein’s influence is first seen at the Leipzig International Exhibition, along with the dioramas of Hahnemann of Kiel, Biebel of Berlin and Muller of Erfurt, all displaying their own figures, and those commissioned from such as Ludwig Frank in large diorama form. In 1933 Gottstein left Germany, and in 1935 founded the British Model Soldier Society. Gottstein persuaded designer and painter friends in both Germany and France to help in the construction of dioramas depicting notable events in English history. But due to the war, many of the figures arrived in England incomplete. The task of turning Gottstein’s ideas into reality fell to his English friends and those friends who had managed to escape from the Continent. Dennis (Denny) C. Stokes, a talented painter and diorama maker in his own right, was responsible for the painting of the backgrounds of all the dioramas, creating a unity seen throughout the whole series. Denny Stokes was given the overall supervision of the fifteen dioramas.

- 1. The Landing of the Romans under Julius Caesar in 55 B.C.

- 2. The Battle of Hastings.

- 3. The Storming of Acre. (Figures by Muller.)

- 4. The Battle of Crecy. (Figures by Muller.)

- 5. The Field of the Cloth of Gold.

- 6. The Queen Elizabeth reviewing her troops at Tilbury.

- 7. The Battle of Marston Moor.

- 8. The Battle of Blenheim. (Painted by Douchkine.)

- 9. The Battle of Plessey.

- 10. The Battle of Quebec. (Engraved by Krunert of Vienna.)

- 11. The Old Guard at Waterloo.

- 12. The Charge of the Light Brigade.

- 13. The Battle of Ulundi. (figures by Ochel, and Petrocochino - pseudonym of Paul Armont.)

- 14. The Battle of Fleurs.

- 15. The D-Day landings.

Krunert, Schirmer, Frank, Frauendorf, Maier, Franz Rieche and Oesterrich were also involved in the manufacture and design of figures for the various dioramas. Krunert (a Viennese), like Gottstein an exile in London, was given the job of engraving for ‘The Battle of Quebec’. Unfortunately, the ‘death of Wolfe’ was found to be inaccurate and had to be re-designed. The names of the vast majority of painters employed by Gottstein are mostly unknown, most lived and worked on the continent, among them Gustave Kenmow, Leopold Rieche, L. Dunekate, M. Alexandre, A. Ochel, Honey Ray and, perhaps Gottstein’s top painter, Vladimir Douchkine (a Russian émigré who lived in Paris). Douchkine was responsible for painting two figures of the Duke of Marlborough on horseback for ‘The Blenheim Diorama’, one of which was used, the other, Gottstein being the true collector, was never released.

Denny Stokes painted all the backgrounds of all the dioramas, Herbert Norris, the Historical Costume Designer, whom Dr. J. F. Lovel-Barnes introduced to Gottstein, was responsible for the costume design of the Ancient Britons, the Normans and Saxons, some of the figures of ‘The Field of the Cloth of Gold’ and the Elizabethan figures for ‘Queen Elizabeth at Tilbury’. Dr. J.F. Lovel-Barnes was himself responsible for the ‘Battle of Blenheim’ diorama, selecting the figures, and arrangement of the scene. Due to World War II, when flat figures became unavailable, Gottstein completed his ideas by using Greenwood and Ball’s 20 mm figures. In time a fifteenth diorama was added, using these 20 mm figures, this diorama representing the ‘D-Day landings’. When all the dioramas were completed, they were displayed along one wall in the Royal United Services Institute Museum. When the museum was closed the fifteen dioramas were distributed to various museums and institutions. The greatest number are to be found at the Glenbow Museum, (130-9th Avenue, S. E. Calgary, Alberta, Canada): RE: 'The Landing of the Romans under Julius Caesar in 55 BC', 'The Battle Of Crecy', 'The Battle of Blenheim', 'The Old Guard at Waterloo', 'The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava'.

The state of these dioramas is one of debate; John Garratt (The World of Model Soldiers) claimed in 1968, that the dioramas “appear to have been partially broken up and individual figures have been sold to collectors”. According to the Glenbow Institute (Barry Agnew, Curator) “the figures are still in reasonable condition, but the plaster groundwork has suffered considerable deterioration”. Unfortunately, there are no photographs available of the dioramas. ‘The Battle of Hastings’ diorama was to be found in the Old Town Museum, Hastings, and is still in reasonable condition. It shows the Norman cavalry charging up Senlac Hill towards the Saxon lines. ‘The Storming of Acre’ is in the Museum of Artillery at the Rotunda, Woolwich. John Garratt, in the "Encyclopedia of Model Soldiers", states that ‘The Field of the Cloth of Gold’ was in the possession of the Royal Military School of Music, Kneller Hall; however, according to the Curator, the diorama had not been in his possession since 1980, nor is it listed in their Accession Book, so the whereabouts of this diorama is unknown.[6]

The Frank Wong dioramas

San Francisco, California artist Frank Wong (born September 22, 1932) created miniature dioramas that depict the San Francisco Chinatown of his youth during the 1930s and 1940s.[7] In 2004, Wong donated seven miniatures of scenes of Chinatown, titled “The Chinatown Miniatures Collection,” to Chinese Historical Society of America (CHSA).[8] The dioramas are on permanent display in CHSA’s Main Gallery:[7][8][9]

- 1. “The Moon Festival”

- 2. “Shoeshine Stand”

- 3. “Chinese New Year”

- 4. “Chinese Laundry”

- 5. “Christmas Scene”

- 6. “Single Room”

- 7. “Herb Store”

Documentary

San Francisco filmmaker James Chan is producing and directing a documentary about Wong and the "changing landscape of Chinatown" in San Francisco.[10] The documentary is tentatively titled, “Frank Wong’s Chinatown.”[7][11]

Other dioramas

Painters of the Romantic era like John Martin and Francis Danby were influenced to create large and highly dramatic pictures by the sensational dioramas and panoramas of their day. In one case, the connection between life and diorama art became intensely circular. On 1 February 1829, John Martin's brother Jonathan, known as "Mad Martin," set fire to the roof of York Minster. Clarkson Stanfield created a diorama re-enactment of the event, which premiered on 20 April of the same year; it employed a "safe fire" via chemical reaction as a special effect. On 27 May, the "safe" fire proved to be less safe than planned: it set a real fire in the painted cloths of the imitation fire, which burned down the theater and all of its dioramas.[12]

Nonetheless, dioramas remained popular in England, Scotland, and Ireland through most of the 19th century, lasting until 1880.

A small scale version of the diorama called the Polyrama Panoptique could display images in the home and was marketed from the 1820s.[13]

Natural history dioramas

Natural history dioramas seek to imitate nature and, since their conception in the late 19th century, aim to “nurture a reverence for nature [with its] beauty and grandeur”.[14] They have also been described as a means to visually preserve nature as different environments change due to human involvement.[15] They were extremely popular during the first half of the 20th century, both in the USA and UK, later on giving way to television, film, and new perspectives on science.[16][17]

Like historical dioramas, natural history dioramas are a mix of two- and three-dimensional elements. What sets natural history dioramas apart from other categories is the use of taxidermy in addition to the foreground replicas and painted background. The use of taxidermy means that natural history dioramas derive not only from Daguerre’s work, but also from that of taxidermists, who were used to preparing specimens for either science or spectacle. It was only with the dioramas’ precursors (and, later on, dioramas) that both these objectives merged. Popular diorama precursors were produced by Charles Willson Peale, an artist with an interest in taxidermy, during the early 19th century. To present his specimens, Peale “painted skies and landscapes on the back of cases displaying his taxidermy specimens”.[18] By the late 19th century, the British Museum held an exhibition featuring taxidermy birds set on models of plants.

The first habitat diorama created for a museum was constructed by Carl Akeley for the Milwaukee Public Museum in 1889,[19] where it is still held. Akeley set taxidermy muskrats on a recreation of their wetland habitat before a realistic painted background. Soon, the concern for accuracy came. Groups of scientists, taxidermists, and artists would go on expeditions to ensure accurate backgrounds and collect specimens,[20] though some would be donated by game hunters.[21]

Natural history dioramas reached the peak of their grandeur with the opening of the Akeley Hall of African Mammals in 1936,[22] which featured large animals, such as elephants, surrounded by even larger scenery.[23]

Nowadays, various institutions lay different claims to notable dioramas. The Milwaukee Public Museum still displays the world’s first diorama, created by Akeley; the American Museum of Natural History, in New York, has what might be the world’s largest diorama: a life-size replica of a blue whale; the Powell-Cotton Museum, in Kent, UK, is known for having the world’s oldest, unchanged, room-sized diorama, built in 1896.

Constructing a diorama

Natural history dioramas consist of 3 parts:

- The painted background

- The foreground

- Taxidermy specimens

Preparations for the background begin on the field, where an artist takes photographs and sketches references pieces. Once back at the museum, the artist has to depict the scenery with as much realism as possible. The challenge lies in the fact that the wall used is curved: this allows the background to surround the display without seams joining different panels. At times the wall also curves upward to meet the light above and form a sky. By having a curved wall, whatever the artist paints will be distorted by perspective; it is the artist’s job to paint in such a way that minimises this distortion.

The foreground is created to mimic the ground, plants and other accessories to scenery. The ground, hills, rocks, and large trees are created with wood, wire mesh, and plaster. Smaller trees are either used in their entirety or replicated using casts. Grasses and shrubs can be preserved in solution or dried to then be added to the diorama. Ground debris, such as leaf litter, is collected on site and soaked in wallpaper paste for preservation and presentation in the diorama. Water is simulated using glass or plexiglass with ripples carved on the surface. For a diorama to be successful, the foreground and background must merge, so both artists have to work together.

Taxidermy specimens are usually the centrepiece of dioramas. Since they must entertain, as well as educate, specimens are set in lifelike poses, so as to convey a narrative of an animal’s life. Smaller animals are usually made with rubber moulds and painted. Larger animals are prepared by first making a clay sculpture of the animal. This sculpture is made over the actual, posed skeleton of the animal, with reference to moulds and measurements taken on the field. A papier-mâché mannequin is prepared from the clay sculpture and the animal’s tanned skin is sewn onto the mannequin. Glass eyes substitute the real ones.

If an animal is large enough the scaffolding which holds the specimen needs to be incorporated into the foreground design and construction.

See also

- Australian War Memorial dioramas

- Armor Modeling and Preservation Society

- Cosmorama

- Cyclorama

- Model airport

- Moving panorama

- Myriorama

- Nativity scene

- Planetarium

- Community (TV series)

Notes

- ↑ Diorama - Word Origin & History - Online Etymology Dictionary - Dictionary.com. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006.

- ↑ Lionel Lambourne, Victorian Painting, London, Phaidon Press, 1999; p. 156.

- ↑ (French) All about Daguerre's diorama in Bry

- ↑ (French) About the diorama on Bry's official website

- ↑ Journal of the British Flat Figure Society: Issue One – April 1986. The Gottstein Dioramas - England’s Flat Heritage. By Jan Redley.

- 1 2 3 Guthrie, Julian. "Frank Wong recalls life in Chinatown through miniature dioramas". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Chinatown Miniatures Collection". Chinese Historical Society of America. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ ""Chinatown in Miniature" Presentation by Artist Frank Wong". Chinese Historical Society of America. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Frank Wong's Chinatown". Good Medicine Picture Company. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Frank Wong and His Chinatown Miniatures". IMDB.com. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Lambourne, p. 157.

- ↑ Science & Society Picture Library: the collections of the Science Museum, the National Railway Museum and the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006; p. 8.

- ↑ Diorama Exhibition at the American Natural History Museum – Retrieved 4 June 2013

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006; p. 10

- ↑ Carla Yanni, Nature’s Museums: Victorian Science and the Architecture of Display, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, p. 150.

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006; p. 13-4

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006; p. 15

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006, p.16

- ↑ Elizabeth Hanson, Animal Attractions: Nature on Display in American Zoos, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 91.

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006, p.18

- ↑ Stephen Christopher Quinn, Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History, Abrams, New York, 2006

References

- Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, L.J.M. Daguerre, The History of The Diorama and the Daguerreotype, Dover Publications, 1968.

- Dioramas Muzeul National de Istorie Naturala Grigore Antipa http://www.antipa.ro/en/categories/27/pages/248

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dioramas. |

- R. D. Wood's Essays on the early history of photography and the Diorama

- The world's largest collection of antique sailing ship dioramas

- World War II Dioramas in 1:35 scale

- A tutorial on how to make a miniature diorama

- A diorama video taken using an Olympus E-PM1 camera

- A diorama in memory of all of the heroes of the axe and in recognition of their service