Diffused lighting camouflage

Diffused lighting camouflage was a form of active camouflage using counter-illumination to match the background, prototyped by the Royal Canadian Navy during World War II.

The concept was to project light on to the sides of a ship so as to make its brightness match its background. For this purpose, projectors were mounted on temporary supports attached to the hull. The prototype was developed to include automatic control of brightness using a photocell.

The prototyped concept was never put into production. The Canadian ideas were however adapted by the US Air Force in its Yehudi lights project.

Concept

.jpg)

Diffused lighting camouflage was explored by the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and tested at sea on corvettes during World War II, and later in the armed forces of the UK and the US.[1]

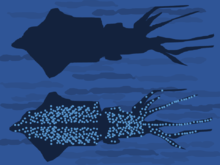

An equivalent strategy, known to zoologists as counter-illumination, is used by many marine organisms, notably cephalopods including the Midwater Squid, Abralia veranyi. The underside is covered with small photophores, organs that produce light. The squid varies the intensity of the light according to the brightness of the sea surface far above, providing effective camouflage by diffusely lighting out the animal's shadow.[2]

In 1940, a Canadian professor at McGill University,[3] Edmund Godfrey Burr, serendipitously stumbled on the principle of counterillumination, or as he called it "diffused-lighting camouflage".[4][5][6] Burr had been tasked by Canada's National Research Council (NRC) to evaluate night observation instruments. With these, he found that aircraft flying without navigation lights remained readily visible as silhouettes against the night sky, which was never completely black. Burr wondered if he could camouflage planes by somehow reducing this difference in brightness. One night in December 1940, Burr saw a plane coming in to land over snow suddenly vanish: light reflected from the snow had illuminated the underside of the plane just enough to cancel out the difference in brightness, camouflaging the plane perfectly. Burr informed the NRC, who told the RCN. They realized that the technique could help to hide ships from German submarines in the Battle of the Atlantic. Before the introduction of centimetre radar, submarines with their small profile could see convoy ships before they were themselves seen. Diffused lighting camouflage might, the RCN believed, redress the balance.[1]

Prototyping

Burr was quickly called to Canada's Naval Services Headquarters to discuss how to apply diffused lighting camouflage. Simple tests in the laboratory served as proof of concept. In January 1941, sea trials began on the new corvette HMCS Cobalt. She was fitted with ordinary light projectors — neither designed for robustness, nor waterproofed — on temporary supports on one side of the hull; brightness was controlled manually. The trial was sufficiently promising for a better prototype to be developed.[1][7]

The second version, with blue-green filters over the projectors, was trialled on board HMCS Chambly in May 1941. This gave better results as the filters removed the reddish bias to the lamps when at low intensity (lower colour temperature). The supports too were retractable, so the delicate projectors could be stowed away for protection when not in use. This second version reduced Chambly's visibility by 50% in most conditions, and sometimes by as much as 75%. This was enough to justify development of a more robust version.[1]

The third version featured a photocell to measure the brightness of the night sky and the ship's side; the projectors' brightness was automatically controlled to balance out the difference. It was tested in September 1941 on the corvette HMCS Kamloops.[1]

Parallel trials of the Canadian diffused lighting equipment were carried out in March 1941 by the Royal Navy on the corvette HMS Trillium; later in 1941, the Royal Navy trialled the General Electric Company's manually operated diffused lighting system on HMS Largs, and then halted the research. The US Navy trialled an automatic system made by General Electric of New York (a different company) in 1942, but soon also halted research. The US Navy sent its control system and projectors to Canada's National Research Council, which installed it on HMCS Edmundston and HMCS Rimouski in 1943.[1][8]

Active service

Both Edmundston and Rimouski were fitted with about 60 light projectors: those on the hull were on retractable supports; those on the superstructure were on fixed supports. Each ship's diffused lighting system was tested systematically in St Margaret's Bay, and then trialled when actually escorting Atlantic convoys in 1943. Experimentally, the diffused lighting reduced the ships' visibility by up to 70%, but at sea the electrical equipment proved too delicate, and frequently malfunctioned. Worse, the system was slow to respond to changes in background lighting, and the Canadian Navy considered the lighting too green.[1]

In September 1943, Rimouski, using her diffused lighting system, but also some navigation lights, approached German submarine U-536 in the Baie des Chaleurs. The intention was to make Rimouski appear as "a small and inoffensive ship" in an operation to trap the submarine, and this appears to have worked as the U-boat did not detect her. However the attack failed, as a wrong signal sent from shore alerted the submarine's commander, Kapitänleutnant Schauenburg; U-536 dived and escaped.[1] She was sunk two months later by the Canadian corvettes Nene and Snowberry on 19 November 1943 while she was attacking Convoy SL 139/MKS 30.[9]

Following Allied victory in the Battle of the Atlantic – through longer-range aircraft, radar, code decryption, and better escort tactics – the need to camouflage ships from submarines greatly decreased, and diffused lighting research became a low priority. The work was halted when the war ended.[1]

In aircraft

.jpg)

Because submarines at the surface could see the dark shape of an attacking aircraft against the night sky, the principle of diffused lighting camouflage also applied to aircraft. British researchers found that the amount of electrical power required to camouflage an aircraft's underside in daylight was prohibitive; and externally mounted light projectors disturbed the aircraft's aerodynamics.[1]

An American version, "Yehudi", using lamps mounted in the aircraft's nose and the leading edges of the wings, was trialled in B-24 Liberators, Avenger torpedo bombers and a Navy glide bomb from 1943 to 1945. By directing the light forwards towards an observer (rather than towards the aircraft's skin), the system provided effective counterillumination camouflage, more like that of marine animals than the Canadian diffused lighting approach.[1][10] But the system never entered active service, as radar became the principal means of detecting aircraft.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ "Midwater Squid, Abralia veranyi". Midwater Squid, Abralia veranyi (with photograph). Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ↑ R.C. Fetherstonhaugh, R.C., 1947, pages 337-341.

- ↑ Burr, 1947, pages 45-54.

- ↑ Burr, 1948, pages 19-35.

- ↑ Richard, Marc. "E. Godfrey Burr and his Contributions to Canadian Wartime Research: A Profile". McGill University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ Sumrall, Robert F. "Ship Camouflage (WWII): Deceptive Art" United States Naval Institute Proceedings. February 1973. pages 67–81

- ↑ Summary Technical Report of Division 16, NDRC. Volume 2: Visibility Studies and Some Applications in the Field of Camouflage. (Washington, D.C.: Office of Scientific Research and Development, National Defense Research Committee, 1946), pages 14-16 and 225-241

- ↑ Kemp, Paul (1997). U-Boats Destroyed: German Submarine Losses in the World Wars. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 158.

- ↑ Bush,, Vannevar; Conant, James; et al. (1946). "Camouflage of Sea-Search Aircraft" (PDF). Visibility Studies and Some Applications in the Field of Camouflage. Office of Scientific Research and Development, National Defence Research Committee. pp. 225–240. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

Sources

- Burr, E. Godfrey. Illumination for Concealment of Ships at Night. Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada (Third series, volume XLI, May 1947), pages 45–54.

- Burr, E. Godfrey. Illumination for Concealment of Ships at Night: Some Technical Considerations. Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada (Third series, volume XLII, May 1948), pages 19–35.

- Fetherstonhaugh, R.C. McGill University at War: 1914-1918, 1939-1945. (Montreal: McGill University, 1947), pages 337-341.

- Hadley, Michael L. U-Boats Against Canada: German Submarines in Canadian Waters. (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1985), pages 180-182.

- Lindsey, George R. No Day Long Enough: Canadian Science in World War II. (Toronto: Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies, 1997), pages 172-173.

- Pickford, R.J. Sublieutenant 'Commando' and Young Corvette Skipper. Salty Dips, Volume 1 (Ottawa: Naval Officers' Association of Canada, 1983), pages 4–5.

- Schuthe, George M. MLs and Mine Recovery. Salty Dips, volume 1 (Ottawa: Naval Officers' Association of Canada, 1983), pages 83.

- Summary Technical Report of Division 16, NDRC. Volume 2: Visibility Studies and Some Applications in the Field of Camouflage. (Washington, D.C.: Office of Scientific Research and Development, National Defense Research Committee, 1946), pages 14–16 and 225-241. [Declassified August 2, 1960].

- Sumrall, Robert F. "Ship Camouflage (WWII): Deceptive Art". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. February 1973. pages 67–81.

- Waddington, C.H. O.R. in World War 2: Operational Research Against the U-Boat. (London: Elek Science, 1973), pages 164-167.