Richard Whittington

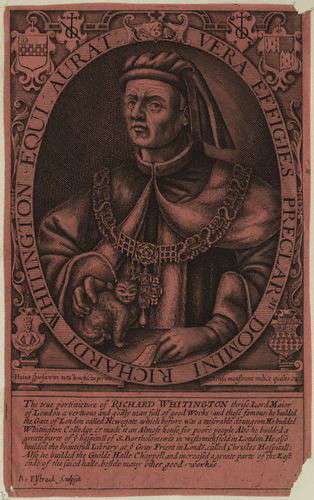

Original engraving depicted a skull under his palm, but printseller Peter Stent requested it changed to a cat, to meet popular expectations.

Sir Richard Whittington (c. 1354–1423[1]) was a medieval merchant and a politician. He is also the real-life inspiration for the English folk tale Dick Whittington and His Cat. He was four times Lord Mayor of London, a member of parliament and a sheriff of London. In his lifetime he financed a number of public projects, such as drainage systems in poor areas of medieval London, and a hospital ward for unmarried mothers. He bequeathed his fortune to form the Charity of Sir Richard Whittington which, nearly 600 years later, continues to assist people in need.[2]

Biography

He was born in Gloucestershire, England, at Pauntley in the Forest of Dean,[3] although his family originated from Kinver in Staffordshire, England, where his grandfather Sir William de Whittington was a knight at arms.[4] His date of birth is variously given as in the 1350s and he died in London in 1423. However, he was a younger son and so would not inherit his father's estate as the eldest son might expect to do. Consequently he was sent to the City of London to learn the trade of mercer. He became a successful trader, dealing in valuable imports such as silks and velvets, both luxury fabrics, much of which he sold to the Royal and noble court from about 1388. There is indirect evidence that he was also a major exporter to Europe of much sought after English woollen cloth such as broadcloth. From 1392 to 1394 he sold goods to Richard II worth £3,500 (equivalent to more than £1.5m today).[5] He also began money-lending in 1388, preferring this to outward shows of wealth such as buying property. By 1397 he was also lending large sums of money to the King.[3]

In 1384 Whittington had become a Councilman. In 1392 he was one of the city's delegation to the King at Nottingham at which the King seized the City of London's lands because of alleged misgovernment. By 1393, he had become an alderman and was appointed Sheriff by the incumbent mayor, William Staundone,[6] as well as becoming a member of the Mercers' Company. When Adam Bamme, the mayor of London, died in June 1397, Whittington was imposed on the city by the King as Lord Mayor of London two days later to fill the vacancy with immediate effect. Within days Whittington had negotiated with the King a deal in which the city bought back its liberties for £10,000 (nearly £4m today).[5] He was elected mayor by a grateful populace on 13 October 1397.[3]

The deposition of Richard II in 1399 did not affect Whittington and it is thought that he merely acquiesced in the coup led by Bolingbroke. Whittington had long supplied the new king, Henry IV, as a prominent member of the landowning elite and so his business simply continued as before. He also lent the new king substantial amounts of money. He was elected mayor again in 1406—during 1407 he was simultaneously Mayor in both London and Calais[7]—and in 1419.[3] In 1416, he became Member of Parliament for the City of London, and was also in turn influential with Henry IV's son, Henry V, also lending him large amounts of money and serving on several Royal Commissions of oyer and terminer. For example, Henry V employed him to supervise the expenditure to complete Westminster Abbey. Despite being a moneylender himself he was sufficiently trusted and respected to sit as a judge in usury trials in 1421. Whittington also collected revenues and import duties. A long dispute with the Company of Brewers over standard prices and measures of ale was won by Whittington.[3]

Benefactions

In his lifetime Whittington donated much of his profit to the city and left further endowments by his Will. He financed:

- the rebuilding of the Guildhall

- a ward for unmarried mothers at St Thomas' Hospital

- drainage systems for areas around Billingsgate and Cripplegate

- the rebuilding of his parish church, St Michael Paternoster Royal

- a public toilet seating 128 called Whittington's Longhouse in the parish of St Martin Vintry that was cleansed by the River Thames at high tide

- most of Greyfriars library

He also provided accommodation for his apprentices in his own house. He passed a law prohibiting the washing of animal skins by apprentices in the River Thames in cold, wet weather because many young boys had died through hypothermia or drowning in the strong river currents.

Death and bequests

Whittington died in March 1423. In 1402 (aged 48) he had married Alice, daughter of Sir Ivo FitzWarin (or Fitzwarren) of Wantage in Berkshire (now Oxfordshire), but she predeceased him in 1411. They had no children. He was buried in the church of St Michael Paternoster Royal, to which he had donated large sums during his lifetime. The tomb is now lost, and the mummified cat found in the church tower in 1949 during a search for its location probably dates to the time of the Wren restoration.[8]

In the absence of heirs, Whittington left £7,000 in his will to charity, in those days a large sum, with a modern-day equivalence of about £3m.[5] Some of this was used to

- rebuild Newgate Prison and Newgate and accommodation in it for the Sheriffs and Recorder which is the forerunner of that in the Old Bailey

- build the first library in Guildhall (the ancestor of the modern Guildhall Library)

- repair St Bartholomew's Hospital

- the creation of his 'college' i.e. almshouse and hospital originally at St Michael's

- install some of the first public drinking fountains

The almshouses were relocated in 1966 to Felbridge near East Grinstead. Sixty elderly women and a few married couples currently live in them. The Whittington Charity also disburses money each year to the needy through the Mercers' Company. The Whittington hospital is now at Archway in the London Borough of Islington and a small statue of a cat along Highgate Hill further commemorates his legendary feline.

Dick Whittington—stage character

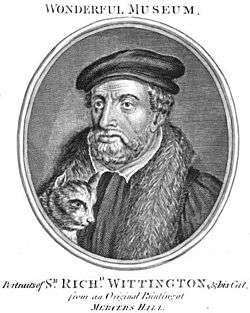

Printed in New Wonderful Museum, Vol. III (1805). "from the original painting at Mercer's Hall".

The gifts left in Whittington's will made him well known and he became a character in an English story that was adapted for the stage as a play, The History of Richard Whittington, of his lowe byrth, his great fortune, in February 1604.[9] In the 19th century this became popular as a pantomime called Dick Whittington and His Cat, very loosely based on Richard Whittington. There are several versions of the traditional story, which tells how Dick, a boy from a poor Gloucestershire family, sets out for London to make his fortune, accompanied by, or later acquiring, his cat. At first he meets with little success, and is tempted to return home. However, on his way out of the city, whilst climbing Highgate Hill from modern-day Archway, he hears the Bow Bells of London ringing, and believes they are sending him a message. There is now a large hospital on Highgate Hill, named the Whittington Hospital, after this supposed episode. A traditional rhyme associated with this tale is:

- Turn again, Whittington,

- Once Lord Mayor of London!

- Turn again, Whittington,

- Twice Lord Mayor of London!

- Turn again, Whittington,

- Thrice Lord Mayor of London!

On returning to London, Dick embarks on a series of adventures. In one version of the tale, he travels abroad on a ship, and wins many friends as a result of the rat-catching activities of his cat; in another he sends his cat and it is sold to make his fortune. Eventually he does become prosperous, marries his master's daughter Alice Fitzwarren (the name of the real Whittington's wife), and is made Lord Mayor of London three times. The common belief that he served three rather than four times as Lord Mayor stems from the City's records 'Liber Albus' compiled at his request by the City Clerk John Carpenter wherein his name appears only three times as the remainder term of his deceased predecessor Adam Bamme and his own consequent term immediately afterwards appear as one entry for 1397.

As the son of gentry Whittington was never very poor and there is no evidence that he kept a cat. Whittington may have become associated with a thirteenth-century Persian folktale about an orphan who gained a fortune through his cat,[10] but the tale was common throughout Europe at that time.[11] Folklorists have suggested that the most popular legends about Whittington—that his fortunes were founded on the sale of his cat, who was sent on a merchant vessel to a rat-beset Eastern emperor—originated in a popular 17th-century engraving by Renold Elstracke in which his hand rested on a cat, but the picture only reflects a story already in wide circulation.[12] Elstracke's oddly-shaped cat was in fact a later replacement by printseller Peter Stent for what had been a skull in the original, with the change being made to conform to the story already in existence, to increase sales.[13]

There was also known to be a painted portrait of Whittington shown with a cat, hanging at Mercer Hall, but it was reported that the painting had been trimmed down to smaller size, and the date "1572" that appears there was something painted after the cropping, which raises doubt as to the authenticity of the date, though Malcolm who witnessed it ca. early 1800s felt the date should be taken in good faith.[14] The print published in The New Wonderful Museum (vol. III, 1805, pictured above) is presumably a replica of this painting.[15]

Notes

- ↑ "The Saturday Magazine, Volume 4". John William Parker, 1834 - Page 201. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

He was knighted, it is said, by King Henry the Fifth....

- ↑ "Charitable Trusts". Worshipful Company of Mercers. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sutton, Anne (2004). "Whittington, Richard (c.1350–1423)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29330.

- ↑ Whittington Inn, Stourbridge Express and Star, 19 February 2007

- 1 2 3 About Us Measuring Worth Calculator

- ↑ Riley, Henry Thomas, ed. (1868). "Election of Richard Whityngton to the Shrievalty". Memorials of London and London life, in the XIIIth, XIVth, and XVth centuries. Being a series of extracts, local, social, and political, from the early archives of the City of London, A.D. 1276–1419. Corporation of the City of London. pp. 533,534. OCLC 884588.

the said Mayor chose Richard Whytyndone, [sic] Alderman...to be Sheriff...of London for the ensuing year.

- ↑ The true authority in Calais lay with the "Captain"—usually an aristocrat. Whittington's position was "Mayor of The staple", representing the town's merchants. Arnold-Baker, Charles (1996). "Calais". The companion to British history (2001 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 220. ISBN 0-415-18583-1.

- ↑ Kent, William, ed. (1937). "St Michael Paternoster Royal". An Encyclopaedia of London. London: J. M. Dent. p. 149. OCLC 492430064.

- ↑ Stationers' Register, quoted in Halliwell-Phillipps, James (1860). A dictionary of old English plays, existing either in print or in manuscript. Soho, London: John Russell Smith. p. 210. OCLC 457585907.

- ↑ Broderip, William (1847). Zoological Recreations. London: H. Colburn. p. 206. OCLC 457155095.

- ↑ Clouston, William (1887). Popular Tales and Fictions: Their Migrations and Transformations. London: Blackwood. p. 304. OCLC 246807577.

- ↑ Tiffin, Walter Francis (1866). Gossip about portraits. London: Bohn. p. 59. OCLC 1305737.

- ↑ van Vechten, Carl (1920). The Tiger in the House. New York: Knopf. p. 150. OCLC 249848844.

- ↑ James Peller Malcolm in Londinium Redivivum, Vol. 4 (1807).

- ↑ Granger, William; Caulfield, James (1805), "History of the Memorable Sir Richard Whittington", The New Wonderful Museum, and Extraordinary Magazine, vol. 3, Alex. Hogg & Co., p. 1420

References

- The History of Sir Richard Whittington by T. H. (1885), from Project Gutenberg

- Dick Whittington and His Cat

External links

- Nine part radio play from BBC Radio Gloucestershire

- The History of Whittington, as collected by Andrew Lang in The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- Dick Whittington and His Cat. London: Jarrold, 1900

- "Who Was Dick Whittington?" Museum of London 17 December 2006 (Free educational program: Storytelling)Event details

- Dick Whittington and his Cat at The Great Cat

- Dick Whittington and His Cat as retold by Rohini Chowdhury